The South Atlantic, Past and Present

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Struggle Between the Dutch and the Portuguese for the Control of The

The Dutch and the Portuguese in West Africa : empire building and Atlantic system (1580-1674) Ribeiro da Silva, F.I. Citation Ribeiro da Silva, F. I. (2009, June 24). The Dutch and the Portuguese in West Africa : empire building and Atlantic system (1580-1674). Retrieved from https://hdl.handle.net/1887/13867 Version: Not Applicable (or Unknown) Licence agreement concerning inclusion of doctoral thesis in the License: Institutional Repository of the University of Leiden Downloaded from: https://hdl.handle.net/1887/13867 Note: To cite this publication please use the final published version (if applicable). CHAPTER FIVE: STRUGGLING FOR THE ATLANTIC: THE INTER-CONTINENTAL TRADE The struggle between the Dutch and the Portuguese for the control of the Atlantic inter- continental trade has been debated in the international historiography for the past fifty years. Chapter 5 offers a re-exam of this conflict from a West African perspective. On the one hand, we will argue that the Dutch and the Portuguese developed different inter- continental circuits to and via West Africa and sailed in completely distinct ways in the Atlantic. The Portuguese trading circuits via West Africa were highly specialized with one or two main areas of embarkation. Initially, the Dutch tried a similar strategy: to use one or two main areas of supply in West Africa and one main area of disembarkation in the Americas: north-east Brazil. However, after the loss of Brazil and Angola, the Dutch tendency was to have a more diversified set of commercial circuits linking different regions of West Africa with several areas in the Americas. -

La Lettre Energy Geotechnics

La Lettre Energy Geotechnics Special release / August 2015 Alstom power plants Editorial A long-lasting partnership Energy engineering in the broadest sense brings together a multitude of skills, among A specific sequencing of the geotechnical which geotechnics may seem marginal. engineering tasks has therefore been This is not the case at all, as TERRASOL developed: demonstrates every day through its • Analysis of available data (often limited) contribution to a variety of projects and initial feasibility study focusing on (hydroelectric power, oil & gas, wind turbines, the general principles of geotechnical thermal power plants, nuclear power, etc), in structures (types of foundations that all regions of the world. can be considered, soil consolidation/ reinforcement issues, dewatering, etc), Projects related to hydroelectric power • Drafting of the first version of the Soil give rise to serious geological and Baseline Assumptions report, the geotechnical issues because of the types baseline document of the call for tenders of structures they involve (dams, tunnels), phase which defines the assumptions and TERRASOL has been working on such made by ALSTOM for its costing and projects practically since it was founded, which may become contractual, thanks to its competencies in underground • Preparation of the first version of the structures and slope stability. Soil Risk Analysis report, in order to get insight into the identified risks of slippage, Centrale HEP Plomin, Croatia Large storage tanks are another of our • Preparation of the specifications for the preferred areas of work, because of the Since 2006 and a first expert assessment additional soil testing intended to obtain pertinence of our approaches in soil-structure report on problems on a power plant site in data that is lacking and/or for which the interaction. -

The Kongolese Atlantic: Central African Slavery & Culture From

The Kongolese Atlantic: Central African Slavery & Culture from Mayombe to Haiti by Christina Frances Mobley Department of History Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Laurent Dubois, Supervisor ___________________________ Bruce Hall ___________________________ Janet J. Ewald ___________________________ Lisa Lindsay ___________________________ James Sweet Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History in the Graduate School of Duke University 2015 i v ABSTRACT The Kongolese Atlantic: Central African Slavery & Culture from Mayombe to Haiti by Christina Frances Mobley Department of History Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Laurent Dubois, Supervisor ___________________________ Bruce Hall ___________________________ Janet J. Ewald ___________________________ Lisa Lindsay ___________________________ James Sweet An abstract of a dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History in the Graduate School of Duke University 2015 Copyright by Christina Frances Mobley 2015 Abstract In my dissertation, “The Kongolese Atlantic: Central African Slavery & Culture from Mayombe to Haiti,” I investigate the cultural history of West Central African slavery at the height of the trans-Atlantic slave trade, the late eighteenth century. My research focuses on the Loango Coast, a region that has received -

T. R. Brainerd2

KSHOP IN POLmCM, AND POLICY ANAiV 513NQ&THPAPM INDIANA UNlVfiW BLOQMHXi-STON, JN0IANA _ p^ THE SARDINELLA FISHERY OFF THE COAST OF WEST AFRICA; THE CASE OF A COMMON PROPERTY RESOURCE by T. R. Brainerd2 Paper presented at the Second Annual Conference of the International Association for the Study of Common Property (IASCP), September 26-29, 1991, University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, Canada. Fisheries Economist Intern, Agriculture, Food and Nutrition Sciences Division/International Development Research Centre (AFNS/IDRC), Ottawa, Canada. THE SARDINELLA FISHERY OFF THE COAST OF WEST AFRICA; THE CASE OF A COMMON PROPERTY RESOURCE by T. R. Brainerd Fisheries Economist Intern Agriculture/ Food and Nutrition Sciences Division/ International Development Research Centre (AFNS/IDRC) P.O. Box 8500, Ottawa/ Ontario/ CANADA RIG 3H9 Abstract Two species of sardinella/ 5. aurita and S. maderenele occur off the coast of West Africa in the Eastern Central Atlantic. Their distribution extends from Mauritania to the south of Angola with concentrations of distinct populations in three geographic sectors due to favorable environmental conditions. Because of their pattern of migration (both up and down along the coast and inshore- offshore pattern of movements)/ individual stocks are found in the territorial waters of two or more coastal countries at different stages of their life cycles. This makes it necessary for coastal countries to share information on the status of the stocks and for cooperation on the management of the fishery. The activities of national institutions/ sub-regional and regional bodies/ and international agencies in promoting the management of this common property resource are highlighted and discussed in terms of their effectiveness and relevance. -

The Maritime Dimension of the European Union's and Germany's

ISPSW Strategy Series: Focus on Defense and International Security Issue The Maritime Dimension of the European Union’s and Germany’s No. 229 Security and Defence Policy in the 21st Century May 2013 The Maritime Dimension of the European Union’s and Germany’s Security and Defence Policy in the 21st Century Maritime Security of the European Union (MAREU) Prof. Dr. Carlo Masala and Konstantinos Tsetsos, M.A. May 2013 Executive Summary This study focuses on the centres of gravity and goals of a future maritime security policy of Germany and the European Union (EU) for the 21st century. Prepared under the working title MAREU (Maritime Security of the European Union) the project concentrates on the EU’s maritime security environment. The strategic dimension of security related developments at the European periphery, Germany’s and the EU’s maritime and energy security represent the central political and societal research objectives of the MAREU project. This study addresses economic developments, legal and illegal migration as well as existing maritime security measures of international organisations. The Mediterranean, Baltic Sea, Gulf of Guinea and South China Sea are the study’s geographical focus. The project discusses the necessary framework for a German and European maritime security strategy by anticipating potential future security threats and an analysis of existing national and international strategies and measures. In its conclusion the study outlines the required future capabilities of the Bundeswehr and offers guidelines, recommendations and reform proposals in order to enhance the future coordination of German and European maritime security cooperation. About ISPSW The Institute for Strategic, Political, Security and Economic Consultancy (ISPSW) is a private institute for research and consultancy. -

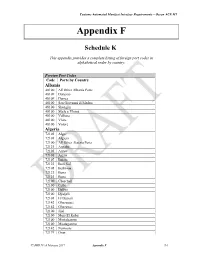

Appendix F – Schedule K

Customs Automated Manifest Interface Requirements – Ocean ACE M1 Appendix F Schedule K This appendix provides a complete listing of foreign port codes in alphabetical order by country. Foreign Port Codes Code Ports by Country Albania 48100 All Other Albania Ports 48109 Durazzo 48109 Durres 48100 San Giovanni di Medua 48100 Shengjin 48100 Skele e Vlores 48100 Vallona 48100 Vlore 48100 Volore Algeria 72101 Alger 72101 Algiers 72100 All Other Algeria Ports 72123 Annaba 72105 Arzew 72105 Arziw 72107 Bejaia 72123 Beni Saf 72105 Bethioua 72123 Bona 72123 Bone 72100 Cherchell 72100 Collo 72100 Dellys 72100 Djidjelli 72101 El Djazair 72142 Ghazaouet 72142 Ghazawet 72100 Jijel 72100 Mers El Kebir 72100 Mestghanem 72100 Mostaganem 72142 Nemours 72179 Oran CAMIR V1.4 February 2017 Appendix F F-1 Customs Automated Manifest Interface Requirements – Ocean ACE M1 72189 Skikda 72100 Tenes 72179 Wahran American Samoa 95101 Pago Pago Harbor Angola 76299 All Other Angola Ports 76299 Ambriz 76299 Benguela 76231 Cabinda 76299 Cuio 76274 Lobito 76288 Lombo 76288 Lombo Terminal 76278 Luanda 76282 Malongo Oil Terminal 76279 Namibe 76299 Novo Redondo 76283 Palanca Terminal 76288 Port Lombo 76299 Porto Alexandre 76299 Porto Amboim 76281 Soyo Oil Terminal 76281 Soyo-Quinfuquena term. 76284 Takula 76284 Takula Terminal 76299 Tombua Anguilla 24821 Anguilla 24823 Sombrero Island Antigua 24831 Parham Harbour, Antigua 24831 St. John's, Antigua Argentina 35700 Acevedo 35700 All Other Argentina Ports 35710 Bagual 35701 Bahia Blanca 35705 Buenos Aires 35703 Caleta Cordova 35703 Caleta Olivares 35703 Caleta Olivia 35711 Campana 35702 Comodoro Rivadavia 35700 Concepcion del Uruguay 35700 Diamante 35700 Ibicuy CAMIR V1.4 February 2017 Appendix F F-2 Customs Automated Manifest Interface Requirements – Ocean ACE M1 35737 La Plata 35740 Madryn 35739 Mar del Plata 35741 Necochea 35779 Pto. -

Bristol, Africa and the Eighteenth Century Slave Trade To

BRISTOL RECORD SOCIETY'S PUBLICATIONS General Editor: JOSEPH BE1TEY, M.A., Ph.D., F.S.A. Assistant Editor: MISS ELIZABETH RALPH, M.A., F.S.A. VOL. XLII BRISTOL, AFRICA AND THE EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY SLAVE TRADE TO AMERICA VOL. 3 THE YEARS OF DECLINE 1746-1769 BRISTOL, AFRICA AND THE EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY SLAVE TRADE TO AMERICA VOL. 3 THE YEARS OF DECLINE 1746-1769 EDITED BY DAYID RICHARDSON Printed for the BRISTOL RECORD SOCIETY 1991 ISBN 0 901538 12 4 ISSN 0305 8730 © David Richardson Bristol Record Society wishes to express its gratitude to the Marc Fitch Fund and to the University of Bristol Publications Fund for generous grants in support of this volume. Produced for the Society by Alan Sutton Publishing Limited, Stroud, Glos. Printed in Great Britain CONTENTS Page Acknowledgements vi Introduction . vii Note on transcription xxxii List of abbreviations xxxiii ·Text 1 Index 235 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS In the process of ·compiling and editing the information on Bristol voyages to Africa contained in this volume I have received assistance and advice from various individuals and organisations. The task of collecting the material was made much easier from the outset by the generous help and advice I received from the staff at the Public Record Office, the Bristol Record Office, the Bristol Central Library and the Bristol Society of Merchant Venturers. I am grateful to the Society of Merchant Venturers for permission to consult its records and to cite material from them. I am also indebted to the British Academy for its generosity in awarding me a grant in order to allow me to complete my research on Bristol voyages to Africa. -

Bristol, Africa and the Eighteenth Century Slave Trade to America, Vol 1

BRISTOL RECORD SOCIETY'S PUBLICATIONS General Editor: PROFESSOR PATRICK MCGRATH, M.A. Assistant General Editor: MISS ELIZABETH RALPH, M.A., F.S.A. VOL. XXXVIII BRISTOL, AFRICA AND THE EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY SLAVE TRADE TO AMERICA VOL. 1 THE YEARS OF EXPANSION 1698--1729 BRISTOL, AFRICA AND THE EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY SLAVE TRADE TO AMERICA VOL. 1 THE YEARS OF EXPANSION 1698-1729 EDITED BY DAVID RICHARDSON Printed for the BRISTOL RECORD SOCIETY 1986 ISBN 0 901583 00 00 ISSN 0305 8730 © David Richardson Produced for the Society by Alan Sutton Publishing Limited, Gloucester Printed in Great Britain CONTENTS Page Acknowledgements vi Introduction vii Note on transcription xxix List of Abbreviations xxix Text 1 Index 193 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS In the process of compiling and editing the information on Bristol trading voyages to Africa contained in this volume I have been fortunate to receive assistance and encouragement from a number of groups and individuals. The task of collecting the material was made much easier from the outset by the generous help and advice given to me by the staffs of the Public Record Office, the Bristol Record Office, the Bristol Central Library and the Bristol Society of Mer chant Venturers. I am grateful to the Society of Merchant Venturers for permission to consult its records and to use material from them. My thanks are due also to the British Academy for its generosity in providing me with a grant in order to allow me to complete my research on Bristol voyages to Africa. Finally I am indebted to Miss Mary Williams, the City Archivist in Bristol, and Professor Patrick McGrath, the General Editor of the Bristol Record Society, for their warm response to my initial proposal for this volume and for their guidance and help in bringing it to fruition. -

Gulf of Guinea

Gulf of Guinea Sea - Seek Ebook Sailing guide / Guide nautique Gulf of Guinea NE Atlantic Ocean September 2021 http://www.sea-seek.com September 2021 Gulf of Guinea Gulf of Guinea http://www.sea-seek.com September 2021 Gulf of Guinea Table of contents Gulf of Guinea...................................................................................................... 1 1 - Romanche Trench .......................................................................................... 3 2 - Sierra Leone.................................................................................................... 5 2.1 - Freetown - Ferry Terminal ................................................................... 5 3 - Liberia ............................................................................................................. 7 3.1 - Monrovia .............................................................................................. 7 4 - Abidjan............................................................................................................ 8 5 - Takoradi.......................................................................................................... 8 6 - Sekondi ............................................................................................................ 9 7 - Tema .............................................................................................................. 10 8 - Port De Lome................................................................................................ 11 9 - Cotonou ........................................................................................................ -

Inferring Seasonal Movements of Tropical Tunas Between Regions in the Eastern Atlantic Ocean from Catch Per Unit Effort

SCRS/2015/094 Collect. Vol. Sci. Pap. ICCAT, 72(3): 747-785 (2016) INFERRING SEASONAL MOVEMENTS OF TROPICAL TUNAS BETWEEN REGIONS IN THE EASTERN ATLANTIC OCEAN FROM CATCH PER UNIT EFFORT Michelle Sculley1, David Die1 SUMMARY Catch per unit effort data from the ICCAT Task II database are standardized in eight regions in the eastern Atlantic Ocean for skipjack tuna Katsuwonus pelamis, yellowfin tuna, Thunnus albacares, and bigeye tuna, T. obesus. Data are evaluated to describe seasonal changes in relative abundance to inform movement patterns of the three species. Seasonal trends are observed in the three northernmost regions, the Azores, Canary Islands, and Senegal regions. The patterns in these regions suggest a seasonal movement north along the African coastline from the spring through the fall. Each of the three species has different timings of movements. Bigeye tuna begin their movement north first followed by skipjack and yellowfin moving north last, in accordance to their physiological adaptations to cold water. In the regions within the Gulf of Guinea, changes in relative abundance due to movement cannot be distinguished from changes due to recruitment. RÉSUMÉ Les données de prise par unité d'effort extraites de la base de données de la tâche II de l'ICCAT sont standardisées en huit régions de l'océan Atlantique pour le listao (Katsuwonus pelamis), l'albacore (Thunnus albacares) et le thon obèse (T. obesus). Les données sont évaluées pour décrire les changements saisonniers de l'abondance relative afin de fournir des informations sur les schémas de déplacement de ces trois espèces. Les tendances saisonnières sont observées dans les trois régions les plus septentrionales, les Açores, les îles Canaries et le Sénégal. -

Piracy and Maritime Crime

U.S. Naval War College U.S. Naval War College Digital Commons Newport Papers Special Collections 1-2010 Piracy and Maritime Crime Bruce A. Elleman Andrew Forbes David Rosenberg Follow this and additional works at: https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/usnwc-newport-papers Recommended Citation Elleman, Bruce A.; Forbes, Andrew; and Rosenberg, David, "Piracy and Maritime Crime" (2010). Newport Papers. 35. https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/usnwc-newport-papers/35 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Special Collections at U.S. Naval War College Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Newport Papers by an authorized administrator of U.S. Naval War College Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Color profile: Disabled Composite Default screen Cover This perspective aerial view of Newport, Rhode Island, drawn and published by Galt & Hoy of New York, circa 1878, is found in the American Memory Online Map Collections: 1500–2003, of the Library of Congress Geography and Map Division, Washington, D.C. The map may be viewed at http://hdl.loc.gov/ loc.gmd/g3774n.pm008790. Inside Front.ps I:\_04 Jan 2010\_NP35\NP_35.vp Monday, January 11, 2010 12:33:08 PM Color profile: Disabled Composite Default screen Piracy and Maritime Crime Historical and Modern Case Studies Bruce A. Elleman, Andrew Forbes, and David Rosenberg, Editors N ES AV T A A L T W S A D R E NAVAL WAR COLLEGE PRESS C T I O N L L U E E G H E Newport, Rhode Island T R I VI IBU OR A S CT MARI VI NP_35.ps I:\_04 Jan 2010\_NP35\NP_35.vp Friday, January 08, 2010 8:36:20 AM Color profile: Disabled Composite Default screen To Charles W. -

21/5/2021 War Risk Navigation Limitations

21/5/2021 WAR RISK NAVIGATION LIMITATIONS 1. NAVIGATION PROVISIONS (L) Eritrea This coverage shall extend worldwide, but, unless and to the extent otherwise agreed by the Insurers in This exclusion shall only apply South of 15°N accordance with Clause 2, the vessel or craft insured hereunder shall not enter sail for or deviate towards the (M) Indian Ocean Territorial Waters of any of the Countries or places, or any other waters described in the Listed Areas as set out Indian Ocean means Indian Ocean, Gulf of Aden, and Southern Red Sea. below in Clause 3. The waters enclosed by the following boundaries: 2. BREACH OF NAVIGATION PROVISIONS (a) on the north-west, by the Red Sea, south of Latitude 15°N (a) If the Insured wishes to secure continuation of coverage under this insurance for a voyage which would (b) on the northeast, from the Yemen border at 16°38.5’N, 53°6.5’E to high seas point14°55’N, 53°50’E otherwise breach Clause 1, the Insured shall give notice to the Insurers and shall only undertake such voyage if (c) on the east, by a line from high seas point 14°55’N, 53°50’E to high seas point 10°48’N,60°15’E, thence to high seas point 6°45’S, 48°45’E the Insured agrees with the Insurers any amended terms of cover and any additional premium which may be required by the Insurers. (d) and on the southwest, by the Somalia border at 1°40’S, 41°34’E, to high seas point6°45’S, 48°45’E (b) In the event of any breach of any of the provisions of Clause 1, the Insurers shall not be liable for any loss, Excepting coastal waters of adjoining territories up to 12 nautical miles offshore unless otherwise provided.