Thesis Text--FGSR

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wechselbeziehungen Zwischen Musik Und Politik in China Und Taiwan

Wechselbeziehungen zwischen Musik und Politik in China und Taiwan DISSERTATION zur Erlangung der Würde des Doktors der Philosophie der Universität Hamburg vorgelegt von Mei-Ling Shyu 徐玫玲 aus Taipei, Taiwan Hamburg 2001 1. Gutachter: Prof. Dr. H. Rösing 2. Gutachter: Prof. Dr. M. Friedrich Für meine Großmutter Koeh A-Ti (1907-1996), die in der japanischen Kolonialzeit geboren und in den 90er Jahren der Demokratie gestorben ist. Wie bei allen ihrer Generation war ihr Leben eng mit den politischen Spannungen Taiwans verwoben. Inhaltsverzeichnis VORWORT................................................................................................................... VI EINLEITUNG..................................................................................................................2 TEIL I. GRUNDLAGEN CHINESISCHER MUSIKTHEORIE .........................7 I. MUSIK UND REGIERUNGSPRAXIS ........................................................................8 I. 1. Das Herz des Menschen - Grundlage von Musik und Politik....................8 I. 2. Musik als Hinweis auf die politische Leistungsfähigkeit eines Staates...11 II. MUSIKALISCHE ERZIEHUNG ZUR VERBESSERUNG DER HERZEN........................16 II. 1. Musikalische Erziehung in den historischen Betrachtungen...................16 II. 2. Was ist gute Musik eigentlich? ................................................................22 II. 3. Zum politischen Zweck ............................................................................29 III. LI UND MUSIK ALS GUTE REGIERUNG ...............................................................33 -

Shanghai Symphony Orchestra in ‘C’ Major (1879 to 2010)

This item was submitted to Loughborough University as a PhD thesis by the author and is made available in the Institutional Repository (https://dspace.lboro.ac.uk/) under the following Creative Commons Licence conditions. For the full text of this licence, please go to: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/2.5/ Shanghai Symphony Orchestra in ‘C’ Major (1879 to 2010) By Mengyu Luo A Doctoral thesis Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements For the award of Doctor of Philosophy Loughborough University 15th March © by Mengyu Luo (2013) 1 Abstract Shanghai Symphony Orchestra is a fascinating institution. It was first founded in 1879 under the name of ‘Shanghai Public Band’ and was later, in 1907, developed into an orchestra with 33 members under the baton of German conductor Rudolf Buck. Since Mario Paci—an Italian pianist—became its conductor in 1919, the Orchestra developed swiftly and was crowned ‘the best in the Far East’ 远东第一 by a Japanese musician Tanabe Hisao 田边尚雄 in 1923. At that time, Shanghai was semi-colonized by the International Settlement and the French Concession controlled by the Shanghai Municipal Council and the French Council respectively. They were both exempt from local Chinese authority. The Orchestra was an affiliated organization of the former: the Shanghai Municipal Council. When the Chinese Communist Party took over mainland China in 1949, the Orchestra underwent dramatic transformations. It was applied as a political propaganda tool performing music by composers from the socialist camp and adapting folk Chinese songs to Western classical instruments in order to serve the masses. -

The Double Bass Development in China

THE LITHUANIAN ACADEMY OF MUSIC AND THEATRE FACULTY OF MUSIC STRING DEPARTMENT SHAONAN LI THE DOUBLE BASS DEVELOPMENT IN CHINA Study Program: Music Performance (Double Bass) Master’s Thesis Advisor: assoc. prof., dr. Audra Versekėnaitė (signature)... ...................................... Vilnius, 2020 LIETUVOS MUZIKOS IR TEATRO AKADEMIJA SĄŽININGUMO DEKLARACIJA DĖL TIRIAMOJO RAŠTO DARBO 2020 m. gegužės 21 d. Patvirtinu, kad mano tiriamasis rašto darbas „The double bass development in China“ yra parengtas savarankiškai. 1. Šiame darbe pateikta medžiaga nėra plagijuota, tyrimų duomenys yra autentiški ir nesuklastoti. 2. Tiesiogiai ar netiesiogiai panaudotos kitų šaltinių ir/ar autorių citatos ir/ar kita medžiaga pažymėta literatūros nuorodose arba įvardinta kitais būdais. 3. Su pasekmėmis, nustačius plagijavimo ar duomenų klastojimo atvejus, esu susipažinęs(- usi) ir jas suprantu. Shaonan Li (Parašas) (Vardas, pavardė) 1 Abstract Master thesis “The Double Bass development in China” presents the introduction and development of this musical instrument in China. In the first chapter, the double bass in China, I will describe the efforts of early Chinese double bassists such as Zheng Daren (b. 1927) and Shao Genbao (b. 1930) to help the advancement of the instrument in the country. I will also portray the background of musical education in China at that time (1949–1979), with a focus on Zhengkai Ye (no information available so far), who strove to improve Chinese double bass students’ performance skills. I will also introduce some traditional Chinese folk instruments with similar techniques of playing, such as the erhu, a very beautiful traditional string instrument. Both the double bass and the erhu need a wonderful vibrato and good control of the player’s right hand, and both can be used to play the same repertoire, such as 《二泉映月》 (Two Springs Reflect the Moon), composed by Yanjun Hua (1893–1950) in 1949, or 《梁祝》 (Butterfly Lovers), composed by Zhanhao He (b. -

Performing Chinese Contemporary Art Song

Performing Chinese Contemporary Art Song: A Portfolio of Recordings and Exegesis Qing (Lily) Chang Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Elder Conservatorium of Music Faculty of Arts The University of Adelaide July 2017 Table of contents Abstract Declaration Acknowledgements List of tables and figures Part A: Sound recordings Contents of CD 1 Contents of CD 2 Contents of CD 3 Contents of CD 4 Part B: Exegesis Introduction Chapter 1 Historical context 1.1 History of Chinese art song 1.2 Definitions of Chinese contemporary art song Chapter 2 Performing Chinese contemporary art song 2.1 Singing Chinese contemporary art song 2.2 Vocal techniques for performing Chinese contemporary art song 2.3 Various vocal styles for performing Chinese contemporary art song 2.4 Techniques for staging presentations of Chinese contemporary art song i Chapter 3 Exploring how to interpret ornamentations 3.1 Types of frequently used ornaments and their use in Chinese contemporary art song 3.2 How to use ornamentation to match the four tones of Chinese pronunciation Chapter 4 Four case studies 4.1 The Hunchback of Notre Dame by Shang Deyi 4.2 I Love This Land by Lu Zaiyi 4.3 Lullaby by Shi Guangnan 4.4 Autumn, Pamir, How Beautiful My Hometown Is! by Zheng Qiufeng Conclusion References Appendices Appendix A: Romanized Chinese and English translations of 56 Chinese contemporary art songs Appendix B: Text of commentary for 56 Chinese contemporary art songs Appendix C: Performing Chinese contemporary art song: Scores of repertoire for examination Appendix D: University of Adelaide Ethics Approval Number H-2014-184 ii NOTE: 4 CDs containing 'Recorded Performances' are included with the print copy of the thesis held in the University of Adelaide Library. -

Searchable PDF Format

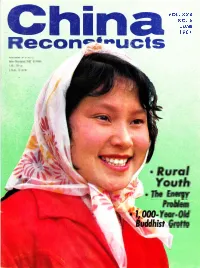

vo[. xxx NO. 6 JUNE r98r R Austraha: ASt) 72 Neu Zealand: NZ $ 0.t14 UK:39 p US.A:S0.7ti o Rurql Youth o lhe EnqgY Prcilm Yeor-Old Grollo China's first high-l1ux nuclear reactor goes into operation. Here, the !:eactor core is being installed. Plrrtto hr Liu l.ltibin PUBLISHED MONTHTY IN ENGLISH, FRENCH, SPANISH, AMBIC, GERMAN, PORTUGUESE AND CHINESE BY THE CHINA TYETFARE INSNTUTE (sOONG CHING LINg, CHAIRMANI vor. xxx No. 6 JUNE 1981 Articles of the Month CONTENTS Young Folks in the Country Villoge Youth Young People of a Rural Brigade E Eighty percent of Chino's young people live in the o The Youth Experimental Farm B countryside. A series describes their current mood o Into the World Market 1.1 os they work to chonge the foce of Chino. Poge 5 o More Marriages in Zhongshahai 13 Econonny/Science China's First High-Flux Reactor 5B The Making of a Young Science Writer 56 Saving Energy for More Production 34 The Xiamen Special Economic Zone 68 Stockbreeding The Horse of the Future-and the Past 16 Culture/Arts The Energy Problem National Exhibition by Young Artists 30 Xiao Youmei, Pioneer in Music Education 24 lndustriol production rcse 8.4/" in 1980 while output The Dazu Treasure-House of Carvings 50 of energy declilned slightly. Conservotion, energy Engraving on a Human Hair 43 etficiency, ond new lesources ore the onswer. The Art of Miniature 42 Poge 3l ln Guangzhou's Orchid Garden hz s Educotion The Youth A* Erhibition The Overseas Chinese University 18 Friendship How some of Grino's best yoring Memories of Chin.a 40 ortists tockle new themes ond new YMCA Seminar Tour from U.S. -

Chinese Music Across Generations – Case Studies of Conservatory Musicians in 20Th-Century China

Chinese Music across Generations – Case Studies of Conservatory Musicians in 20th-Century China Frank Kouwenhoven, Lin Chen and Helen Rees Abstract: This paper looks at ways in which some instrumental realms of traditional Chinese music have survived in or alongside modern music conservatory contexts, and how subsequent generations of musicians in China have dealt with the challenges of new teaching methods or performing styles. Four case studies will be presented here in some detail, with additional references to some other musicians recently interviewed. Frank Kouwenhoven introduces Li Guangzu,1 widely regarded as one of the founders of modern style pipa (lute) playing in China. Li never studied or taught at a music conservatory, but was very influential. Next, together with Lin Chen, Kouwenhoven traces the musical and spiritual development of Chinese guqin (seven-string zither) master Lin Youren (Lin Chen's father). He was among the first generation of qin students to be trained at a music conservatory and witnessed the clash of tradition with modernity first-hand. He struggled with it for much of his life. Thirdly, the fate of Cantonese instrumental ensemble music will briefly be traced via the stories of senior fiddle player Yu Qiwei (Hong Kong) and his son Yu Lefu (Guangzhou [Canton]). The latter built up an impressive career as a modern style erhu (two-stringed fiddle) virtuoso at the Xinghai Conservatory in Guangzhou, but he also began to teach the favorite traditional music of his father, trying to be “more traditional” than his dad. Such a smooth continuation of tradition is rare in Chinese conservatory contexts, but one further example of this is provided by Helen Rees; she looks at two Shanghai-based performers of the endblown bamboo flute xiao, an instrument too quiet and introspective to be favored by many conservatory students. -

Sposobin Remains. a Soviet Harmony Textbook's Twisted Fate in China

Sposobin Remains A Soviet Harmony Textbook’s Twisted Fate in China1 Wai Ling Cheong, Ding Hong In 1937–38, Igor V. Sposobin and three co-authors at the Moscow Conservatory published Uchebnik garmonii [Harmony Textbook]. This was the first officially approved harmony textbook in the USSR, which came to be adopted as “the basic textbook for courses on harmony in the mu- sic schools of the Soviet Union” (Vladimir Protopopov, 1960). Characterized by its promulgation of the “scientifically based” theory of harmonic functions, this book was destined to be read by many more musicians in a foreign land. In 1955–56, Boris A. Arapov decreed at meetings held at the Central Conservatory of Music in China that the problem posed by the ethnicization of harmo- ny should be solved by combining musical elements that are considered ethnically distinct with functional harmony. Wu Zuqiang, who had studied at the Moscow Conservatory in the 1950s before he headed the Central Conservatory in the 1980s, published a chapter from Uchebnik garmonii already in 1955. The first Chinese translation of the whole book by Zhu Shimin was then published in 1957–58. The book soon attained canonic status in China and has been used in vir- tually all Chinese music institutions up to the present day. It is listed in the entrance examination syllabi of selected conservatories and reputable music theorists have published model answers to the exercises it contains. This article investigates how the Chinese reception of Uchebnik garmonii diverges from the sources that had inspired Sposobin and his colleagues to compose it in the first place, and throws light on the far-reaching impacts and ramifications of Uchebnik garmonii in China. -

萧友梅与中国音乐教育 Chopin Hsiao-Yiu-Mei and Chinese Music Education

萧友梅与中国音乐教育 Chopin Hsiao-yiu-mei and Chinese Music Education 26 July 2018 Organizer: 26 July 2018 Organizer: OstasiatischesOstasiatisches Institut Institut (Sinologie) (Sinologie) der der Universität Universität Leipzig Leipzig 主办单位:莱比锡大学 上海音乐学院 承办单位:莱比锡大学东亚研究所 上海音乐学院图书馆 协办单位:台湾师范大学音乐数位典藏中心 策展人:杨燕迪 柯若朴 史寅 黄均人 韩斌 撰稿:韩斌 英文协力:张源源 展览地点:莱比锡大学东亚研究所 策展人:杨燕迪 柯若朴 史寅 韩斌 撰稿:韩斌 英文协力:张源源 萧友梅与中国音乐教育 Program Chopin Hsiao Yiu-mei and Chinese Music Education Hsiao Yiu-mei: Query (1922), Lyrics by Yi Weizhai Huang Tzu: Three Wishes of the Rose (1932), Lyrics by Long Qi Qing Zhu: The Yangtze Love (1930), Lyrics by Li Zhiyi Soprano: Shih-Hsin Huang Piano: Wenjing Hu He Luting:Buffalo Boy's Flute (1934) Wang Jianzhong: Silver Clouds Chasing the Moon (1975) Piano: Yu Yifan Composers Hsiao Yiu-mei 1884-1940 Hsiao Yiu-mei was a noted Chinese music educator and composer. He was among the first batch of publicly funded students to be sent to Germany by the government of the Republic of China in 1912. He studied at Leipzig University and Königliches Konservatorium der Musik zu Leipzig (now the University of Music and Theatre Leipzig), where he completed the Ph.D. His doctoral thesis was "Eine Geschichtliche Untersuchung über das Chine- sische Orchester bis zum 17. Jahrhundert (Historical Research on the Pre-Seventeenth Century Chinese Orchestra)" (1916). In October 1916, he entered the philosophy department of Berlin University where he continued research. After he came back to China, Cai Yuanpei supported him to found China's first specialized institute of higher education for music, the National Insti- tute for Music (in 1949 it was renamed the Shanghai Conservatory of Music , which it remains today). -

China and the West: Music, Representation, and Reception

0/-*/&4637&: *ODPMMBCPSBUJPOXJUI6OHMVFJU XFIBWFTFUVQBTVSWFZ POMZUFORVFTUJPOT UP MFBSONPSFBCPVUIPXPQFOBDDFTTFCPPLTBSFEJTDPWFSFEBOEVTFE 8FSFBMMZWBMVFZPVSQBSUJDJQBUJPOQMFBTFUBLFQBSU $-*$,)&3& "OFMFDUSPOJDWFSTJPOPGUIJTCPPLJTGSFFMZBWBJMBCMF UIBOLTUP UIFTVQQPSUPGMJCSBSJFTXPSLJOHXJUI,OPXMFEHF6OMBUDIFE ,6JTBDPMMBCPSBUJWFJOJUJBUJWFEFTJHOFEUPNBLFIJHIRVBMJUZ CPPLT0QFO"DDFTTGPSUIFQVCMJDHPPE Revised Pages China and the West Revised Pages Wanguo Quantu [A Map of the Myriad Countries of the World] was made in the 1620s by Guilio Aleni, whose Chinese name 艾儒略 appears in the last column of the text (first on the left) above the Jesuit symbol IHS. Aleni’s map was based on Matteo Ricci’s earlier map of 1602. Revised Pages China and the West Music, Representation, and Reception Edited by Hon- Lun Yang and Michael Saffle University of Michigan Press Ann Arbor Revised Pages Copyright © 2017 by Hon- Lun Yang and Michael Saffle All rights reserved This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publisher. Published in the United States of America by the University of Michigan Press Manufactured in the United States of America c Printed on acid- free paper 2020 2019 2018 2017 4 3 2 1 A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the British Library. Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Names: Yang, Hon- Lun, editor. | Saffle, Michael, 1946– editor. Title: China and the West : music, representation, and reception / edited by Hon- Lun Yang and Michael Saffle. Description: Ann Arbor : University of Michigan Press, 2017. | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2016045491| ISBN 9780472130313 (hardcover : alk. -

Education and Research on Chinese Traditional Music

EDUCATION AND RESEARCH ON CHINESE TRADITIONAL MUSIC Xiao Mei [萧梅] Abstract ‘Education and Research on Chinese Traditional Music’ has a history of thousands of years, making it difficult to present this topic comprehensively. Therefore, the larger theme “Education and Research on Chinese Traditional Music within a Dialogue of Civilizations and Cultures” that is partly discussed here will be limited to the contemporary history and the appearance of Chinese traditional music after the first encounters with ‘so-called’ Western music. This paper is mainly a reflection on the author’s personal experiences, views on certain aspects of the topic, and a wider consideration of historical events that are connected to it.1 Keywords education, tradition, Chinese music, dialogue, cultural views AGE OF EMPIRE VERSUS NATION-STATE From a Chinese perspective, 1840 is regarded as the year when modern Chinese history began. In 1840, when the Opium War broke out, gunfire from the West opened the gates of China. After that, the traditional idea that all lands belong to the emperor was challenged. The system that had held for thousands of years, where the key relationships were between groups in one land that one emperor ruled, was altered. From 1840, the key feature was the international relationship between China and various other countries. After 1840, many revolutions and changes in China failed and people began to wonder how to turn this country into a powerful nation, and how to save its endangered independence. This also inspired the social elites to build a new national spirit and promote the establishment of a powerful new nation-state. -

Report Title Xi, Baikang (Um 1979) Bibliographie : Autor Xi, Chen

Report Title - p. 1 of 235 Report Title Xi, Baikang (um 1979) Bibliographie : Autor 1979 [Maupassant, Guy de]. Mobosang duan pian xiao shuo xuan du. Mobosang ; Xi Baikang. (Shanghai : Shanghai yi wen chu ban she, 1979). [Übersetzung ausgewählter Kurzgeschichten von Maupassant]. [WC] Xi, Chen (um 1923) Bibliographie : Autor 1923 [Russell, Bertrand]. Luosu lun wen ji. Luosu zhu ; Yang Duanliu, Xi Chen, Yu Yuzhi, Zhang Wentian, Zhu Pu yi. Vol. 1-2. (Shanghai : Shang wu yin shu guan, 1923). (Dong fang wen ku ; 44). [Enthält] : E guo ge ming de li lun ji shi ji. Übersetzung von Russell, Bertrand. The practice and theory of Bolshevism. (London : Allen & Unwin, 1920). She hui zhu yi yu zi you zhu yi. Hu Yuzhi yi. Übersetzung von Russell, Bertrand. Socialism and liberal ideals. In : Living age ; no 306 (July 10, 1920). Wei kai fa guo zhi gong ye. Yang Duanliu yi. Übersetzung von Russell, Bertrand. Industry in undeveloped countries. In : Atlantic monthly ; 127 (June 1921). Xian jin hun huan zhuang tai zhi yuan yin. Übersetzung von Russell, Bertrand. Causes of present chaos. In : The prospects of industrial civilization. (London : Allen & Unwin, 1923). Zhongguo guo min xing de ji ge te dian. Yu Zhi [Hu Yuzhi] yi. Übersetzung von Russell, Bertrand. Some traits in the Chinese character. In : Atlantic monthly ; 128 (Dec. 1921). Zhongguo zhi guo ji di wei. Zhang Wentian yi. [WC,Russ3] Xi, Chu (um 1920) Bibliographie : Autor 1920 [Whitman, Walt]. Huiteman zi you shi xuan yi. Xi Chu yi. In : Ping min jiao yu ; no 20 (March 1920). [Selected translations of Whitman's poems of freedom]. -

FACING the PAST, LOOKING to the FUTURE: Chinese Composers in the 21St Century

FACING THE PAST, LOOKING TO THE FUTURE: Chinese Composers in the 21st Century OCTOBER 19 – 22, 2018 • BARD COLLEGE AND NEW YORK CITY The China Now Music Festival is inspired by the richness and vitality of music in contemporary Chinese society. Western Classical music is developing at a phenomenal speed in China, where two new con- servatories have been founded and several dozen symphony orchestras established in the last decade alone. Equally exciting is the abundance of new music creation and the freshness and vitality that Chinese composers bring to us here in the West. China Now is a collaboration between the US-China Music Institute and the Central Conservatory of Music in Beijing, dedicated to promoting an under- standing and appreciation of music from contemporary China through an annual series of themed concerts and academic activities. With China Now, we hope to bring people and cultures from East and West together through music. The theme of this year’s festival is Facing the Past, Looking to the Future: Chinese Composers in the 21st Century. In our October 19th opening concert at the Fisher Center at Bard College we will perform a mix of works that both face the past and look to the future. The October 21st Lincoln Center concert then focuses on how Chinese composers have explored and responded to the past through their music. The program features compositions that confront three wrenching events in modern Chinese history: the first Opium War of 1839–42, the Nanjing Massacre of 1937, and the “sent-down youth” movement of the 1966-76 Cultural Revolution period, when students were sent “up into the mountains and down into the countryside.” The October 22nd Carnegie Hall concert changes direction and looks to the future with an exciting program consisting entirely of world-premiere compositions by members of the distin- guished composition faculty of the Central Conservatory of Music in Beijing.