What Sort of Minded Being Has Language? Anticipatory Dynamics, Arguability and Agency in a Normatively and Recursively Self-Transforming Learning System Part 2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PASA 2005 Final Report.Pdf

PAN AFRICAN SANCTUARY ALLIANCE 2005 MANAGEMENT WORKSHOP REPORT 4-8 June 2005 Mount Kenya Safari Lodge, Nanyuki, Kenya Hosted by Pan African Sanctuary Alliance / Sweetwaters Chimpanzee Sanctuary Photos provided by Tacugama Chimpanzee Sanctuary – Sierra Leone (cover), PASA member sanctuaries, and Doug Cress. A contribution of the World Conservation Union, Species Survival Commission, Conservation Breeding Specialist Group (CBSG) and Primate Specialist Group (PSG). © Copyright 2005 by CBSG IUCN encourages meetings, workshops and other fora for the consideration and analysis of issues related to conservation, and believes that reports of these meetings are most useful when broadly disseminated. The opinions and views expressed by the authors may not necessarily reflect the formal policies of IUCN, its Commissions, its Secretariat or its members. The designation of geographical entities in this book, and the presentation of the material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of IUCN concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Prepared by participants in the PASA 2005 Management Workshop, Mount Kenya, Kenya, 4th – 8th June 2005 W. Mills, D. Cress, & N. Rosen (Editors). Conservation Breeding Specialist Group (SSC/IUCN). 2005. Pan African Sanctuary Alliance (PASA) 2005 Workshop Report. Additional copies of the Pan African Sanctuary Alliance (PASA) 2005 Workshop Report can be ordered through the IUCN/SSC Conservation -

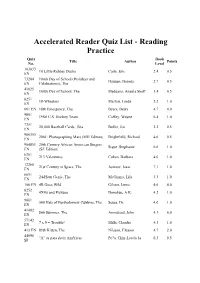

Accelerated Reader Quiz List - Reading Practice Quiz Book Title Author Points No

Accelerated Reader Quiz List - Reading Practice Quiz Book Title Author Points No. Level 103833 10 Little Rubber Ducks Carle, Eric 2.4 0.5 EN 73204 100th Day of School (Holidays and Haugen, Brenda 2.7 0.5 EN Celebrations), The 41025 100th Day of School, The Medearis, Angela Shelf 1.4 0.5 EN 8251 18-Wheelers Maifair, Linda 5.2 1.0 EN 661 EN 18th Emergency, The Byars, Betsy 4.7 4.0 9801 1980 U.S. Hockey Team Coffey, Wayne 6.4 1.0 EN 7351 20,000 Baseball Cards...Sea Buller, Jon 2.5 0.5 EN 900355 2061: Photographing Mars (MH Edition) Brightfield, Richard 4.6 0.5 EN 904851 20th Century African American Singers Sigue, Stephanie 6.6 1.0 EN (SF Edition) 6201 213 Valentines Cohen, Barbara 4.0 1.0 EN 12260 21st Century in Space, The Asimov, Isaac 7.1 1.0 EN 6651 24-Hour Genie, The McGinnis, Lila 3.3 1.0 EN 166 EN 4B Goes Wild Gilson, Jamie 4.6 4.0 8252 4X4's and Pickups Donahue, A.K. 4.2 1.0 EN 9001 500 Hats of Bartholomew Cubbins, The Seuss, Dr. 4.0 1.0 EN 41482 $66 Summer, The Armistead, John 4.3 6.0 EN 57142 7 x 9 = Trouble! Mills, Claudia 4.3 1.0 EN 413 EN 89th Kitten, The Nilsson, Eleanor 4.7 2.0 44096 "A" es para decir Am?ricas Pe?a, Chin-Lee/de la 6.3 0.5 SP Accelerated Reader Quiz List - Reading Practice Quiz Book Title Author Points No. -

Folia De Reis, a Brazilian Spiritual Journey Through Song Welson Alves Tremura

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2004 With an Open Heart: Folia De Reis, a Brazilian Spiritual Journey Through Song Welson Alves Tremura Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF MUSIC WITH AN OPEN HEART: FOLIA DE REIS, A BRAZILIAN SPIRITUAL JOURNEY THROUGH SONG By WELSON ALVES TREMURA A Dissertation submitted to the School of Music in partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2004 Copyright 2004 Welson Alves Tremura All Rights Reserved The members of the Committee approve the dissertation of Welson Alves Tremura defended on April 5, 2004. _____________________________ Dale A. Olsen Professor Directing Dissertation _____________________________ Anthony Oliver-Smith Outside Committee Member _____________________________ Michael B. Bakan Committee Member _____________________________ Larry Crook Committee Member The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii The folia de reis high-pitched voices singing in the distance are memories of a childhood of music and celebrations that go back to the early 1970s when playing soccer in a field not larger than a basketball court or flying a kite were the highest point of most children in that part of Brazil. The folia groups could be heard in the distance with the tala or high pitch voice singing the last part of the refrain. These sounds could typically be heard echoing throughout the surrounding neighborhoods of Olímpia, São Paulo during the second half of the month of December and early part of January. -

ANNEX 3 ICC-01/09-02/11-67-Anx3 21-04-2011 2/84 EO PT

ICC-01/09-02/11-67-Anx3 21-04-2011 1/84 EO PT No. ICC-01/09-02/11 21-4-11 ANNEX 3 ICC-01/09-02/11-67-Anx3 21-04-2011 2/84 EO PT A PROGRESS REPORT TO THE HON. ATTORNEY-GENERAL BY THE TEAM ON UPDATE OF POST ELECTION VIOLENCE RELATED CASES IN WESTERN, NYANZA, CENTRAL, RIFT-VALLEY, EASTERN, COAST AND NAIROBI PROVINCES MARCH, 2011 NAIROBI ICC-01/09-02/11-67-Anx3 21-04-2011 3/84 EO PT TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER SUBJECT PAGE TRANSMITTAL LETTER IV 1. INTRODUCTION 1 2. GENDER BASED VIOLENCE CASES 7 3. WESTERN PROVINCE 24 3. RIFT VALLEY PROVINCE 30 4. NYANZA PROVINCE 47 5. COAST PROVINCE 62 6. NAIROBI PROVINCE 66 7. CENTRAL PROVINCE 69 8. STATISTICAL ANALYSIS 70 9. CONCLUSION 73 10. APPENDICES ICC-01/09-02/11-67-Anx3 21-04-2011 4/84 EO PT APPENDIX (NO.) LIST OF APPENDICES APP. 1A - Memo from CPP to Hon. Attorney General APP.1B - Memo from CPP to Hon. Attorney General APP.1C - Update on 2007 Post Election Violence offences As at 4th March, 2010 (police commissioner’s report) APP. 1D - Update by Taskforce on Gender Based Violence Cases (police commissioner’s report) APP. 2 - Memo to Solicitor- General from CPP APP. 3 - Letter from PCIO Western APP. 4 - Letter from PCIO Rift Valley APP.5 - Cases Pending Under Investigations in Rift Valley on special interest cases APP.6 - Cases where suspects are known in Rift Valley but have not been arrested APP.7 - Letter from PCIO Nyanza APP.8 - Letter from PCIO Coast APP.9 - Letter from PCIO Nairobi APP.10 - Correspondences from the team ICC-01/09-02/11-67-Anx3 21-04-2011 5/84 EO PT The Hon. -

Unraveling the Evolutionary History of Orangutans (Genus: Pongo)- the Impact of Environmental Processes and the Genomic Basis of Adaptation

Zurich Open Repository and Archive University of Zurich Main Library Strickhofstrasse 39 CH-8057 Zurich www.zora.uzh.ch Year: 2015 Unraveling the evolutionary history of Orangutans (genus: Pongo)- the impact of environmental processes and the genomic basis of adaptation Mattle-Greminger, Maja Patricia Posted at the Zurich Open Repository and Archive, University of Zurich ZORA URL: https://doi.org/10.5167/uzh-121397 Dissertation Published Version Originally published at: Mattle-Greminger, Maja Patricia. Unraveling the evolutionary history of Orangutans (genus: Pongo)- the impact of environmental processes and the genomic basis of adaptation. 2015, University of Zurich, Faculty of Science. Unraveling the Evolutionary History of Orangutans (genus: Pongo) — The Impact of Environmental Processes and the Genomic Basis of Adaptation Dissertation zur Erlangung der naturwissenschaftlichen Doktorwürde (Dr. sc. nat.) vorgelegt der Mathematisch‐naturwissenschaftlichen Fakultät der Universität Zürich von Maja Patricia Mattle‐Greminger von Richterswil (ZH) Promotionskomitee Prof. Dr. Carel van Schaik (Vorsitz) PD Dr. Michael Krützen (Leitung der Dissertation) Dr. Maria Anisimova Zürich, 2015 To my family Table of Contents Table of Contents ........................................................................................................ 1 Summary ..................................................................................................................... 3 Zusammenfassung ..................................................................................................... -

Duncan Public Library Board of Directors Meeting Minutes June 23, 2020 Location: Duncan Public Library

Subject: Library Board Meeting Date: August 25, 2020 Time: 9:30 am Place: Zoom Meeting 1. Call to Order with flag salute and prayer. 2. Read minutes from July 28, 2020, meeting. Approval. 3. Presentation of library statistics for June. 4. Presentation of library claims for June. Approval. 5. Director’s report a. Summer reading program b. Genealogy Library c. StoryWalk d. Annual report to ODL e. Sept. Library Card Month f. DALC grant for Citizenship Corner g. After-school snack program 6. Consider a list of withdrawn items. Library staff recommends the listed books be declared surplus and be donated to the Friends of the Library for resale, and the funds be used to support the library. 7. Consider approving creation of a Student Library Card and addition of policy to policy manual. 8. Old Business 9. New Business 10. Comments a. By the library staff b. By the library board c. By the public 11. Adjourn Duncan Public Library Claims for July 1 through 31, 2020 Submitted to Library Board, August 25, 2020 01-11-521400 Materials & Supplies 20-1879 Demco......................................................................................................................... $94.94 Zigzag shelf, children’s 20-2059 Quill .......................................................................................................................... $589.93 Tissue, roll holder, paper, soap 01-11-522800 Phone/Internet 20-2222 AT&T ........................................................................................................................... $41.38 -

Williams Dissertation

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Don't Show A Hyena How Well You Can Bite: Performance, Race and the Animal Subaltern in Eastern Africa Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/0jf3488f Author Williams, Joshua Publication Date 2017 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Don’t Show A Hyena How Well You Can Bite: Performance, Race and the Animal Subaltern in Eastern Africa by Joshua Drew Montgomery Williams A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Performance Studies and the Designated Emphasis in Critical Theory in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Catherine Cole, Chair Professor Donna Jones Professor Samera Esmeir Professor Brandi Wilkins Catanese Spring 2017 Abstract Don’t Show A Hyena How Well You Can Bite: Performance, Race and the Animal Subaltern in Eastern Africa by Joshua Drew Montgomery Williams Doctor of Philosophy in Performance Studies Designated Emphasis in Critical Theory University of California, Berkeley Professor Catherine Cole, Chair This dissertation explores the mutual imbrication of race and animality in Kenyan and Tanzanian politics and performance from the 1910s through to the 1990s. It is a cultural history of the non- human under conditions of colonial governmentality and its afterlives. I argue that animal bodies, both actual and figural, were central to the cultural and -

Tanzania Chimpanzee Conservation Action Plan 2018-2023

Tanzania Chimpanzee Conservation Action Plan 2018-2023 This plan is written in collaboration with various institutions that have interest and are working tirelessly in conserving chimpanzees in Tanzania. Editorial list i. Dr. Edward Kohi ii. Dr. Julius Keyyu iii. Dr. Alexander Lobora iv. Ms. Asanterabi Kweka v. Dr. Iddi Lipembe vi. Dr. Shadrack Kamenya vii. Dr. Lilian Pintea viii. Dr. Deus Mjungu ix. Dr. Nick Salafsky x. Dr. Flora Magige xi. Dr. Alex Piel xii. Ms. Kay Kagaruki xiii. Ms. Blanka Tengia xiv. Mr. Emmanuel Mtiti Published by: Tanzania Wildlife Research Institute (TAWIRI) Citation: TAWIRI (2018) Tanzania Chimpanzee Conservation Action Plan 2018-2023 TAWIRI Contact: [email protected] Cover page photo: Chimpanzee in Mahale National Park, photo by Simula Maijo Peres ISBN: 978-9987-9567-53 i Acknowledgements On behalf of the Ministry of Natural Resource and Tourism (MNRT), Wildlife Division (WD), Tanzania National Parks (TANAPA), and Tanzania Wildlife Authority (TAWA), the Tanzania Wildlife Research Institute (TAWIRI) wishes to express its gratitude to organizations and individuals who contributed to the development of this plan. We acknowledge the financial support from the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) and the U.S Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) for the planning process. Special thanks are extended to the Jane Goodall Institute (JGI) and Kyoto University for their long-term chimpanzee research in the country that has enhanced our understanding of the species behaviour, biology and ecology, thereby greatly contributing to the development process of this conservation action plan. TAWIRI also wishes to acknowledge contributions by Conservation Breeding Specialist Group - Species Survival Commission of the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), Evaluation and Research Technologies for Health, Inc. -

Thesewaneepurplev72n23051155.Pdf (613.0Kb)

——— &$t ^rtiiattrr |*iir|)lr The Official Organ of the Students of The Un iity of the South 'Vol. LXXII, No. 23 Sl-WAMF, 1 I'NM-'SSKE, MAY 11, 1955 Curriculum Six Men Receive Announced Baker Scholarships Business Courses '55-'56 Increase Scope Eight Freshmen jewanee's Department of Economics Obtain Four-It ear Grants the Department of Eco- irill become and Business next year, and nomics George F. Baker Scholarships have been awarded to six more high in management and mar- school seniors for four years of study at Sewanee, and two four-year full year course in ac- Union Carbide Scholarships have also been awarded, according to an an- offered, according to counting will be nouncement by Dr. Ben F. Cameron, director of admissions. E. Thorogood, head of the James The awards, which may range from full expense down to the minimum department. needed by a winning student, go to:* Dr. Thorogood stated that the de- Jai Conner Clapp of New Albany, artment is now in the process of find- Bernard Dunl; Participants f professor to teach the 1( a new of Columbia, S. C; John Marshall courses. He emphasized that the new Girault of New Orleans, La.; Everett courses are basic in nature and per- WEEKEND OF PARTIES— (Left) Miss Bobbyc Phillip Norwood McCormick of Jacksonville, Select Songs keeping with Sewanee's lib- Kimboll as Kinft and Queen of the Phi Gam Fiji Island Costurr Fla.; Gerald Archibald Nelson of Fair- curriculum. Outgoing president Corky Little with his date, Barbara Sinclai hope, Ala.; and Robert Dale Sweeney For Sing program of for BK ew education lent Dave Lindholm at the Sigma Nu White Rose Formal. -

Wildlife Rights and Human Obligations

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Central Archive at the University of Reading Wildlife Rights and Human Obligations A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Philosophy Julius Kapembwa June 2017 DECLARATION I confirm that this is my own work and the use of materials from other sources has been properly and fully acknowledged. Julius Kapembwa __________________ i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS A look back at early drafts of some chapters in this thesis reminds me how easy it is to underestimate my debt to Brad Hooker and Elaine Beadle—my supervisors—for the state of the finished thesis. With their intellectual guidance and moral support, which sometimes extended beyond my research, my supervisors helped me settle with relative ease into my research. My supervisors will surely be my models for fairness, firmness, and professionalism in any supervision work I will undertake in the future. I was fortunate to have presented my thesis work-in-progress on five occasions in the Department of Philosophy’s vibrant weekly Graduate Research Seminar (GRS). I would like to thank all graduate students for their engagement and critical feedback to my presentations. Special thanks to David Oderberg, who directed the GRS programme and offered important feedback during the sessions. I am thankful to Julia Mosquera, Joseph Connelly, and Matteo Benocci, who were enthusiastic respondents to my presentations. Thank you to George Mason, who kindly read and gave me some written feedback on parts of Chapter 5. This thesis has resulted in, and benefited from, four conference presentations. -

Television Programs Jersey's Magazine

WEEK'S C MPLETE TELEVISION PROGRAMS THE SUNDAY N RTH JERSEY'S ONLY WEEKLY PICTORIAL MAGAZINE N ws Highlights of Clifton East Paterson Fair Lawn Garfield Haledon Hawthorne Lodi Little Falls I•auntain View North Haledon Paterson Passaic Pompton Lakes Prospect Park Tofowa ¾;•yne West Paterson JANUARY 24, 1960 OLYMPIC-BOUND VOL. XXXH, No. 4 WHITE and SHAUGER, A Good Name to Remember for FURNITURE Living Room - Bed Room Dining Room RUGS AND CARPETS A SPECIALTY Quality and Low Price 39 Years Serving the Public 435 STEAIG• STREET (Coruer 20th Ave•) PATEILqON, '•e Place with the Clock" • MUll•rry 4-•81• Headquarters for Engaged Couples THE IDEAL PLACE TO DINE AND WINE ITCHE •.k---'•,q ' SEA• sPEc•I:00D BROlLE• LOBSTER • -- DAILY OYSTERS - CLAM - COD FI•tt - SWORD FISH - DAILY DINNERS Star in "The Fabulous Fifties" Jan. 31 lb8 BEL•ON• AVe. [Cot. Burhsnt),HALEDON - . - •mbert 5-q885 - . ...:.:.:.J.ii•:.:.:.,:,:::,:/:;"'•/ • • ':',i?:,"'""• ß I.PAR RILLO ! i................'-" ' ! TheMan from Equitableasks- I •"•'"""'-•'-'-'•'•'••:•••:..••...'.•'•:,'L;,•-'o:•----•'"'""•'"''•'"'"•"""•••••'•' _;•_;• ' ß :i•:.iiii!::'.:::' .•-- -:i:::•..............• "'"'•'••:-::--"--:-:-::x'-',•::.•t------ -•" ,••::..':.:::..•It ß I?.,.:"•....•..?:'::::",'',',-....•-.,...'•.•.•,;:•::,...........................- -•.• .•_-. 4:•?...•.._e r_..ß . .-::•'•:.?/:•-............. •... ......................................... "l?-'•-':---'"•i?•il'"'"":""'":•'•,•ji.\ I :::::::::::::::::::::'-*';ø***.•øo,•-**_ ;ø.* •,.",.,_.'.-':-o•'•!;% ' •1•'::' "IlL ß _!•:::f:i•?::.::i?:•' -

District 202 High School 2019-20 First Semester Honor Roll

DISTRICT 202 HIGH SCHOOL 2019-20 FIRST SEMESTER HONOR ROLL Plainfield High School-Central Campus High Honor Roll - Grade 9 DEEYA ALAPATT, MARIANNE ALEXOPOULOS, HAMZA ALI, BRYNN ARNOTT, JONATHAN ARZUAGA, ANDREW AUSTIN, ISAIAH BAEZ, COLIN BAILYE, RECE BARRY, MIA BARTLEMAN, COOPER BARTZ, EMILY BATTAGLIA, KYLE BEHLAND, ARUN BHASIN, KATHALINA BINDAS, JAMES BJORKLUND, ISABEL BOLANOS, JUSTIN BOLKUNOWICZ, MAX BOWEN, JOSEPH BROADWAY, BEVERLY BUARI, MACKENZIE BURGESS, GIANNA CAMARDO, MIGUEL CAMBRAY JR, ELENA CARASEL, PHILLIP CARLTON JR, LOGAN CARMODY, SOPHIA CERDA, LEAH CIRAR, ARIANA COFFEE, LUIS CORREA III, ADAM DABKOWSKI, TESSA DANKO, JOSEPH DEFANO, KATHERINE DEKLERK, ERIK DEMICK, JAZMIN DIAZ, JUSTIN DINH, MADISON DRAFKE, ALEXANDER DVORAK, GAVIN EDDY, KALEIGH ENSWORTH, HANNAH FEWKES, HANNAH FORNELLI, JOSIAH FORNELLI, MOLLY FOX, KAITLYN FRYS, CLAIRE GIESEKE, EMILY GRAHAM, ALI HAMID, EDWARD HANNA, HALEY HARTING, KATELYN HEISEN, KATHERINE HENDERSON, CAITE HENNESSEY, ANDREW HERITAGE, ALEXANDER HERNANDEZ, AMINA HRNJIC, ARIANA IBARRA, BRIANA IBARRA, SARAH IMIG, SAMANTHA JESSEN, ELAYNE KANIA, GRACE KETCHMARK, TAYLOR KIENZLE, AMANDA KISTINGER, CAMRYN KNOBBE, AVA KOZIOROWSKI, CARRIE KRAFT, TAYLOR KUJAK, ELLA LAVOIE, VERONIKA LEGLER, JOCELYN LOPEZ, DAVID LOTARSKI, OSCAR LUEVANO, CAMILA MAGANA, JANET MAGDALENO-CHAVEZ, GRACE MARCHERT, DIANA MARTINEZ, MARTYNA MATEJA, JESSICA MAYDA, RILEY MCKEE, CHRISTOPHER MEDINA, ELISE MINOTT, MARIYA MOISEYTSEVA, JORGEN NELSON, JESTIN NIETO-BROWN, RILEY O'BRIEN, LUKE OSIPCZUK, ASHLYN PACCHETTI, KADIN PARENT, AMELIA PERONA,