2011. Economic and Social Significance of Forests for Africa's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PASA 2005 Final Report.Pdf

PAN AFRICAN SANCTUARY ALLIANCE 2005 MANAGEMENT WORKSHOP REPORT 4-8 June 2005 Mount Kenya Safari Lodge, Nanyuki, Kenya Hosted by Pan African Sanctuary Alliance / Sweetwaters Chimpanzee Sanctuary Photos provided by Tacugama Chimpanzee Sanctuary – Sierra Leone (cover), PASA member sanctuaries, and Doug Cress. A contribution of the World Conservation Union, Species Survival Commission, Conservation Breeding Specialist Group (CBSG) and Primate Specialist Group (PSG). © Copyright 2005 by CBSG IUCN encourages meetings, workshops and other fora for the consideration and analysis of issues related to conservation, and believes that reports of these meetings are most useful when broadly disseminated. The opinions and views expressed by the authors may not necessarily reflect the formal policies of IUCN, its Commissions, its Secretariat or its members. The designation of geographical entities in this book, and the presentation of the material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of IUCN concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Prepared by participants in the PASA 2005 Management Workshop, Mount Kenya, Kenya, 4th – 8th June 2005 W. Mills, D. Cress, & N. Rosen (Editors). Conservation Breeding Specialist Group (SSC/IUCN). 2005. Pan African Sanctuary Alliance (PASA) 2005 Workshop Report. Additional copies of the Pan African Sanctuary Alliance (PASA) 2005 Workshop Report can be ordered through the IUCN/SSC Conservation -

A First Look at Logging in Gabon

Linking forests & people www.globalforestwatch.org A FIRST LOOK AT LOGGING IN GABON An Initiative of WORLD RESOURCES INSTITUTE A Global Forest Watch-Gabon Report What Is Global Forest Watch? GFW’s principal role is to provide access to better What is GFW-Gabon? information about development activities in forests Approximately half of the forests that initially cov- and their environmental impact. By reporting on The Global Forest Watch-Gabon chapter con- ered our planet have been cleared, and another 30 development activities and their impact, GFW fills sists of local environmental nongovernmental orga- percent have been fragmented, or degraded, or a vital information gap. By making this information nizations, including: the Amis de la Nature-Culture replaced by secondary forest. Urgent steps must be accessible to everyone (including governments, et Environnement [Friends of Nature-Culture and taken to safeguard the remaining fifth, located industry, nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), Environment] (ANCE), the Amis Du Pangolin mostly in the Amazon Basin, Central Africa, forest consumers, and wood consumers), GFW [Friends of the Pangolin] (ADP), Aventures Sans Canada, Southeast Asia, and Russia. As part of promotes both transparency and accountability. We Frontières [Adventures without Borders] (ASF), this effort, the World Resources Institute in 1997 are convinced that better information about forests the Centre d’Activité pour le Développement started Global Forest Watch (GFW). will lead to better decisionmaking about forest Durable et l’Environnement [Activity Center for management and use, which ultimately will result Sustainable Development and the Environment] Global Forest Watch is identifying the threats in forest management regimes that provide a full range (CADDE), the Comité Inter-Associations Jeunesse weighing on the last frontier forests—the world’s of benefits for both present and future generations. -

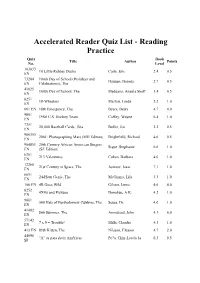

Accelerated Reader Quiz List - Reading Practice Quiz Book Title Author Points No

Accelerated Reader Quiz List - Reading Practice Quiz Book Title Author Points No. Level 103833 10 Little Rubber Ducks Carle, Eric 2.4 0.5 EN 73204 100th Day of School (Holidays and Haugen, Brenda 2.7 0.5 EN Celebrations), The 41025 100th Day of School, The Medearis, Angela Shelf 1.4 0.5 EN 8251 18-Wheelers Maifair, Linda 5.2 1.0 EN 661 EN 18th Emergency, The Byars, Betsy 4.7 4.0 9801 1980 U.S. Hockey Team Coffey, Wayne 6.4 1.0 EN 7351 20,000 Baseball Cards...Sea Buller, Jon 2.5 0.5 EN 900355 2061: Photographing Mars (MH Edition) Brightfield, Richard 4.6 0.5 EN 904851 20th Century African American Singers Sigue, Stephanie 6.6 1.0 EN (SF Edition) 6201 213 Valentines Cohen, Barbara 4.0 1.0 EN 12260 21st Century in Space, The Asimov, Isaac 7.1 1.0 EN 6651 24-Hour Genie, The McGinnis, Lila 3.3 1.0 EN 166 EN 4B Goes Wild Gilson, Jamie 4.6 4.0 8252 4X4's and Pickups Donahue, A.K. 4.2 1.0 EN 9001 500 Hats of Bartholomew Cubbins, The Seuss, Dr. 4.0 1.0 EN 41482 $66 Summer, The Armistead, John 4.3 6.0 EN 57142 7 x 9 = Trouble! Mills, Claudia 4.3 1.0 EN 413 EN 89th Kitten, The Nilsson, Eleanor 4.7 2.0 44096 "A" es para decir Am?ricas Pe?a, Chin-Lee/de la 6.3 0.5 SP Accelerated Reader Quiz List - Reading Practice Quiz Book Title Author Points No. -

Ghana Forest and Wildlife Policy

REPUBLIC OF GHANA GHANA FOREST AND WI LDLIFE POLICY Ministry of Lands and Natural Resources Accra- Ghana 2012 Ghana Forest and Wildlife Policy © Ministry of Land and Natural Resources 2012 For more information, call the following numbers 0302 687302 I 0302 66680 l 0302 687346 I 0302 665949 Fax: 0302 66680 t -ii- Ghana Forest and Wildlife Policy CONTENTS ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS ... ... .. .............. .. ..... ....... ............ .. .. ...... .. ........ .. vii ACKNOWLEDGEMENT ................................................................. .......................... viii FOREWORD ........................................................................................... ...................... ix 1.0 PREAMBLE ............ .. .................................................................. .............................. ! 2.0 Overview Of Forest And Wildlife Sector ..... ............................ .................... ... 3 2 .1 Forest and Wildlife Conservation 3 2.1.1 Forest Plantation Development 4 2.1.2 Collaborative Forest Management 5 2.2 Challenges and Issues in the Forest and Wildlife Sector 2.3 National Development Agenda and Forest and Wildlife Management 2.4 International Concerns on the Global Environment 9 3.0 THE POLICY FRAMEWORK ......................... .. ............................................ ........ 10 3.1 Guiding Principles 10 4 .0 THE FOREST AND WILDLIFE POLICY STATEMENT ............................ ......... 12 4 .1 Aim of the Policy 12 4.2 Objectives of the Policy 12 5.0 Policy Strategies ............ -

"Anora'S Report on the Anyinam

Basel Mission Archives "Anora's Report on the Anyinam District in 1886" Title: "Anora's Report on the Anyinam District in 1886" Ref. number: D-01.45.IV..71 Date: Proper date: 31.12.1886 Description: Describing his community of 37 he writes that some of them are emancipated slaves from Kwahu. But they only stop in Anyinam for two or three years, and then go on ’to the wilderness' (marginal comment by a missionary 'he means the coast') 'to join their fellows; so they are lost to the community. Other Christians are Kwahus. There are only two Anyinam natives in the community. 2 Anyinam people are catechumen, two ex-slaves also, and some children. Of his 8 pupils in the community school, 3 had graduated to the Kibi school. Kwabeng - most of the children of the Christians are not baptised because the mothers are still heathen and will not allow it. Nevertheless there are 15-l7 scholars in Khabeng. He is well contented with the people in Asunafo. They work well together. 12-24 children in the community school. Both in Tumfa and Akropong there were exclusions for adultery. Subject: [Archives catalogue]: Guides / Finding aids: Archives: D - Ghana: D-01 - Incoming correspondence from Ghana up to the outbreak of the First World War: D-01.45 - Ghana 1886: D-01.45.IV. - Begoro Type: Text Ordering: Please contact us by email [email protected] Contact details: Basel Mission Archives/ mission 21, Missionstrasse 21, 4003 Basel, tel. (+41 61 260 2232), fax: (+41 61 260 2268), [email protected] Rights: All the images (photographic and non- photographic) made available in this collection are the property of the Basel Mission / mission 21. -

CIFOR Annual Report 2001: Forests for the Future

Cover AR2001/733 7/14/02 2:05 PM Page 1 Center for International Forestry Research Center for International Forestry Research Forests for the future annual report 2001 CIFOR annual report 2001 “Biodiversity is declining at an unprecedented rate... Half of the tropical rainforests and mangroves have already been lost ... We must reverse this process — preserving as many CIFOR species as possible, and clamping down on illegal and unsustainable fishing and logging practices — while helping people who currently depend on such activities to make a transition to more sustainable ways of earning their living.” Kofi Annan Forests for the future Forestsfor the future CIFOR is one of the 16 Future Harvest centres www.cifor.cgiar.org of the Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research (CGIAR) Cover AR2001/733 7/14/02 2:05 PM Page 2 CIFOR’s heart and soul Contents CIFOR is committed to supporting informed 2. Message from the Chair of the Board of Trustees decision-making processes about forests CIFOR’s research sites that are transparent, accountable and 3. Message from the Director General incorporate the views of traditionally marginalized groups. That means good 4. Working globally governance and decision-making that take into account a wide variety of interests are 4. Working to conserve forest biodiversity central objectives of CIFOR 4. Putting a cap on carbon CIFOR is committed to alleviating rural poverty by helping poor people retain and 5. Financing sustainable forest management obtain access to forest resources, create new resources and earn greater incomes 6. Getting forests on the global agenda from the resources they have. -

Linking FLEGT and REDD+ to Improve Forest Governance

ETF r n i s s u e N o . 5 5 , m a R c h 2 0 1 4 n E w s 55 RodeRick Zagt Linking FLEGT and REDD+ to Improve Forest Governance EuropEan Tropical ForEsT ResEarch Network EuRopEan TRopIcaL ForesT REsEaRch NetwoRk ETFRN News Linking FLEGT and REDD+ to Improve Forest Governance IssuE no. 55, maRch 2014 This publication has been produced with the financial assistance of the European commission’s Thematic programme for Environment and sustainable management of natural Resources, Including Energy; the European Forest Institute’s Eu REDD Facility; the German Federal ministry for Economic cooperation and Development (BmZ); and the Government of the netherlands. The views expressed herein are the sole responsibility of the authors and can in no way be taken to reflect the views of ETFRn, Tropenbos International, the European union or the other participating organizations. published by: Tropenbos International, wageningen, the netherlands copyright: © 2014 ETFRn and Tropenbos International, wageningen, the netherlands Texts may be reproduced for non-commercial purposes, citing the source. citation: Broekhoven, Guido and marieke wit (eds.). (2014). Linking FLEGT and REDD+ to Improve Forest Governance. Tropenbos International, wageningen, the netherlands. xx + 212 pp. Editors: Guido Broekhoven and marieke wit Final editing and layout: Patricia halladay Graphic Design IsBn: 978-90-5113-116-1 Issn: 1876-5866 cover photo: women crossing a bridge near kisangani, DRc. Roderick Zagt printed by: Digigrafi, Veenendaal, the netherlands available from: ETFRn c/o Tropenbos International p.o. Box 232, 6700 aE wageningen, the netherlands tel. +31 317 702020 e-mail [email protected] web www.etfrn.org This publication is printed on Fsc®-certified paper. -

The Impact of Boscia Senegalensis on Clay Turbidity in Fish Ponds: a Case Study of Chilanga Fish Farm

The International Journal of Multi-Disciplinary Research ISSN: 3471-7102, ISBN: 978-9982-70-318-5 THE IMPACT OF BOSCIA SENEGALENSIS ON CLAY TURBIDITY IN FISH PONDS: A CASE STUDY OF CHILANGA FISH FARM. (Conference ID: CFP/853/2018) By: Naomi Zulu [email protected] School of Engineering Information and Communication University, Lusaka, Zambia ABSTRACT The research was carried out at Chilanga Fisheries located in Chilanga District of Lusaka Province of the Republic of Zambia. The total duration for the research project spanned over a period of sixty days beginning 10th April, 2018 to 8th June, 2018. The main aim of the project was to establish the impact of Boscia Senegalensis on clay turbidity in fish ponds. The project was accomplished in two stages. The first part was the preparation of the Boscia Senegalensis solution, the leaves were pounded, mixed with pond water and allowed to settle over a specific period in order to yield a solution. The solution was refined through decanting and filtration and later preserved in the refrigerator before application. The solution was stored in a 5 litre container. The second part involved the use of three identical (2m x 1m x 1m) concrete experimental ponds labelled A, B and C. All the three ponds were filled with pond water to the same level. The preparation of the clay induced source followed immediately after. The experiment was then conducted using ponds “B” and “C”, with pond “B” as a control. The clay induced solution obtained from pond “A” was then added to ponds “B” and “C”. The Boscia Senegalensis solution was added to pond “C” only. -

Folia De Reis, a Brazilian Spiritual Journey Through Song Welson Alves Tremura

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2004 With an Open Heart: Folia De Reis, a Brazilian Spiritual Journey Through Song Welson Alves Tremura Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF MUSIC WITH AN OPEN HEART: FOLIA DE REIS, A BRAZILIAN SPIRITUAL JOURNEY THROUGH SONG By WELSON ALVES TREMURA A Dissertation submitted to the School of Music in partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2004 Copyright 2004 Welson Alves Tremura All Rights Reserved The members of the Committee approve the dissertation of Welson Alves Tremura defended on April 5, 2004. _____________________________ Dale A. Olsen Professor Directing Dissertation _____________________________ Anthony Oliver-Smith Outside Committee Member _____________________________ Michael B. Bakan Committee Member _____________________________ Larry Crook Committee Member The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii The folia de reis high-pitched voices singing in the distance are memories of a childhood of music and celebrations that go back to the early 1970s when playing soccer in a field not larger than a basketball court or flying a kite were the highest point of most children in that part of Brazil. The folia groups could be heard in the distance with the tala or high pitch voice singing the last part of the refrain. These sounds could typically be heard echoing throughout the surrounding neighborhoods of Olímpia, São Paulo during the second half of the month of December and early part of January. -

15. June 2021

Tropical Timber Market Report Volume 25 Number 11 1st – 15th June 2021 The ITTO Tropical Timber Market (TTM) Report, an output of the ITTO Market Information Service (MIS), is published in English every two weeks with the aim of improving transparency in the international tropical timber market. Its contents do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of ITTO. News may be reprinted provided that the ITTO TTM Report is credited. A copy of the publication should be sent to [email protected]. Contents Headlines Page Central/West Africa 2 Digitised trade information to support Ghana’s Ghana 2 exporters 2 Malaysia 3 Malaysia ‐ Strong first quarter exports 4 Indonesia 4 Myanmar 5 Raising productivity and meeting product India 6 Standards the key to competitiveness in Indonesia 5 Vietnam 8 Brazil 10 Myanmar millers warn ‐ Investment in retooling Peru 11 for added value manufacturing too risky 6 Japan 12 Tali imports rising in Vietnam 8 China 18 Online tool to verify the legal origin of wood Europe 20 in Peru 11 North America 24 New strategy ‐ Focus on economic security Currencies and Abbreviations 27 in Japan 12 Ocean Freight 27 Price Indices 28 EUTR shifting from negative to a positive factor for tropical timber 20 Top story US wooden furniture imports dip slightly 25 IMM webinar on tropical timber trade trends during the pandemic Tropical timber trade trends through the pandemic will be discussed during an Independent Market Monitor (IMM) webinar at 10 am‐12 noon on CET June 24. The IMM’s mandate is to monitor trade impacts and perceptions of FLEGT Voluntary Partnership Agreements (VPAs) and market performance of FLEGT‐licensed timber in the EU and UK. -

Human-Wildlife Conflicts

Nature & Faune Vol. 21, Issue 2 Human-Wildlife Conflicts Editor: M. Laverdière Assistant Editors: L. Bakker, A. Ndeso-Atanga FAO Regional Office for Africa [email protected] www.fao.org/world/regional/raf/workprog/forestry/magazine_en.htm FOOD AND AGRICULTURE ORGANISATION OF THE UNITED NATIONS Accra, Ghana 2007 The designations employed and the presentation of material in this information product do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations concerning the legal or development status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The views expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. All rights reserved. Reproduction and dissemination of material in this information product for educational or other non-commercial purposes are authorized without any prior written permission from the copyright holders provided the source is fully acknowledged. Reproduction of material in this information product for resale or other commercial purposes is prohibited without written permission of the copyright holders. Applications for such permission should be addressed to the Chief, Electronic Publishing Policy and Support Branch, Communication Division, FAO,Viale delle Terme di Caracalla, 00153 Rome, Italy or by e-mail to [email protected]. ©FAO 2007 Nature & Faune Vol. 21, Issue 2 Table of Contents Page Editorial 1 News News in Africa 2 News Worldwide 3 FAO News 5 Thematic News in Africa 6 Thematic News Worldwide 6 Special Feature Human-Wildlife Conflict: A Case for Collaboration 8 Madden, F. -

The Economics of the Atewa Forest Range, Ghana

THE ECONOMICS OF THE ATEWA FOREST RANGE, GHANA Living water from the mountain Protecting Atewa water resources THE ECONOMICS OF THE ATEWA FOREST RANGE, GHANA Living water from the mountain Protecting Atewa water resources DISCLAIMER This report was commissioned by IUCN NL and A Rocha Ghana as part of the ‘Living Water from the mountain - Protecting Atewa water resources’ project. The study received support of the Forestry Commission, the Water Resource Commission and the NGO Coalition Against Mining Atewa (CONAMA) and financial assistance of the Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs as part of the Ghana – Netherlands WASH program. The findings, interpretations and conclusions expressed here are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs, IUCN NL, A Rocha Ghana, the Forestry Commission, the Water Resource Commission or the NGO Coalition Against Mining Atewa (CONAMA). Any errors are purely the responsibility of the authors. Not all economic values presented in this study are captured by market mechanisms or translated to financial streams; the values of ecosystem services calculated in this study should therefore not be interpreted as financial values. Economic values represent wellbeing of stakeholders and do not represent the financial return of an investment case. The study should not be used as the basis for investments or related actions and activities without obtaining specific professional advice. This publication may be reproduced in whole or in part and in any form for educational