Rapid Mobility – a Nation on the Move Railways

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The California High Speed Rail Proposal: a Due Diligence Report

September 2008 THE CALIFORNIA HIGH SPEED RAIL PROPO S AL : A DUE DILIGENCE REPOR T By Wendell Cox and Joseph Vranich Project Director: Adrian T. Moore, Ph.D. POLICY STUDY 370 Reason Citizens Against Howard Jarvis Taxpayers Foundation Government Waste Foundation reason.org cagw.org hjta.org/hjtf Reason Foundation’s mission is to advance Citizens Against Government Waste Howard Jarvis Taxpayers Foundation a free society by developing, applying and (CAGW) is a private, nonprofit, nonparti- (HJTF) is devoted to promoting economic promoting libertarian principles, including education, the study of tax policy and san organization dedicated to educating the individual liberty, free markets and the rule defending the interests of taxpayers in the American public about waste, mismanage- of law. We use journalism and public policy courts. research to influence the frameworks and ment, and inefficiency in the federal govern- The Foundation funds and directs stud- actions of policymakers, journalists and ment. ies on tax and economic issues and works opinion leaders. CAGW was founded in 1984 by J. Peter to provide constructive alternatives to the Reason Foundation’s nonpartisan public Grace and nationally-syndicated columnist tax-and-spend proposals from our state policy research promotes choice, competi- Jack Anderson to build support for imple- legislators. tion and a dynamic market economy as the HJTF also advances the interests of mentation of the Grace Commission recom- foundation for human dignity and progress. taxpayers in the courtroom. In appro- mendations and other waste-cutting propos- Reason produces rigorous, peer-reviewed priate cases, HJTF provides legal repre- research and directly engages the policy als. -

High Speed Railway Project Development and Regional Accessibility Improvement: the First Experience in India

FACULTY OF CIVIL AND INDUSTRIAL ENGINEERING Master Degree in Transport System Engineering Thesis High Speed Railway Project Development and Regional Accessibility Improvement: The First Experience in India Supervisor: Candidate: Prof. Eng. Antonio Musso Amal Kuzhiparambil Purushothaman Co-Supervisor: N° 1722321 Dr. Eng. Cristiana Piccioni Academic Year 2018/2019 2 Table of contents Summary 1. Introduction 1.1 Study purpose 1.2 Research background 1.3 Research methodology 1.4 Key issues 2. The Reference framework 2.1 Definition of high-speed rail 2.2 HSR benefits 2.3 HS Rail around the world 2.3.1 Japan 2.3.2 Italy 2.3.3 France 2.3.4 Germany 2.3.5 Spain 2.3.6 China 3. The accessibility concept 3.1 Definition of accessibility 3.2 Accessibility indicators 3.3 A basic benchmarking exercise 4. Accessibility and HSR projects: an insight into international experiences 4.1 The Madrid-Barcelona HSR case study, Spain 4.2 The China HSR case study 4.3 The Seoul HSR case study, Korea 4.4 Brisbane - Melbourne proposed HSR, Australia 5. Building an accessibility indicators framework 5.1 Identification of Accessibility indicators 5.2 A selection of accessibility indicators 5.2.1 Weighted average travel times (Location indicator) 5.2.2 Economic potential 3 5.2.3 Daily accessibility indicator 5.2.4 Economic accessibility 6. Pilot study: the Mumbai – Ahmedabad HSR project 6.1 HSR project background 6.1.1 Necessity of HSR System in India 6.2 Major cities affected by the project 6.2.1 Mumbai 6.2.2 Surat 6.2.3 Vadodara 6.2.4 Ahmedabad 6.3 HSR Project overview 6.3.1 Basic characteristics 6.3.2 Stations 6.3.3 Train operation plans 6.4 Accessibility assessment 6.4.1 Calculation and evaluation of indicators 6.4.2 Weighted average travel times (location indicator) 6.4.3 Economic potential 6.4.4 Daily accessibility indicator 6.4.5 Economic indicator 7. -

China's High-Speed Trains Are Taking On... Massive Migration

01/07/2018 China’s high-speed trains are taking on more passengers in Chinese New Year massive migration | Salvatore Babones Unknown date Salvatore Babones China’s high-speed trains are taking on more passengers in Chinese New Year massive migration This Friday is Chinese New Year, the beginning of the Spring Festival and a weeklong national holiday in China. Nearly everyone in China is on the move. China’s transport ministry expects nearly 3 billion individual trips to be made during this year’s chunyun, or “spring rush.” China is still a poor country, and most of those trips (as much as 80%) will likely be made by long-distance bus. But an increasing number of chunyun travelers will be cruising the country in air-conditioned comfort on China’s world-class high-speed rail network. High-speed rail (HSR) in China has ballooned from a single 113 kilometers (70 mile) demonstration line built specially for the 2008 Beijing Olympics into a 25,000 kilometer (15,500 mile) nationwide system. That first Beijing- Tianjin line took three years to build. The rest of the national network took just another ten. China’s originally-planned “4+4” network of four north-south and four east-west main lines is now nearing completion. An extended “8+8” network of 38,000 kilometers (24,000 miles) of high-speed rail is projected to be operational in 2025. Later improvements are likely to focus on speed rather than distance. That said, China does not explicitly define exactly what constitutes “high- speed” rail, and definitive statistics are hard to come by. -

Acta Asiatica Varsoviensia No. 24

ACTA ASIATICA VARSOVIENSIA NO. 24 ASKON ACTA ASIATICA VARSOVIENSIA NO. 24 ACTA ASIATICA VARSOVIENSIA Editor-in-Chief Board of Advisory Editors MARIA ROMAN S£AWIÑSKI NGUYEN QUANG THUAN KENNETH OLENIK ABDULRAHMAN AL-SALIMI Subject Editor JOLANTA SIERAKOWSKA-DYNDO JERZY ZDANOWSKI BOGDAN SK£ADANEK LEE MING-HUEI ZHANG HAIPENG Institute of Mediterranean and Oriental Cultures Polish Academy of Sciences ACTA ASIATICA VARSOVIENSIA NO. 24 ASKON Publishers Warsaw 2011 Publication co-financed by the State Committee for Scientific Research Secretary Agata Wójcik English Text Consultant Stephen Hedrick © Copyright by Institute of Mediterranean and Oriental Cultures, Polish Academy of Sciences, Warsaw 2011 Printed in Poland This edition prepared, set and published by Wydawnictwo Naukowe ASKON Sp. z o.o. Stawki 3/1, 00193 Warszawa tel./fax: (+48) 22 635 99 37 www.askon.waw.pl [email protected] PL ISSN 08606102 ISBN 9788374520553 ACTA ASIATICA VARSOVIENSIA is abstracted in The Central European Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities Contents ROMAN S £ AWIÑSKI, The New Confucianism vs. the Development of East Asia (2) ................................................................................................. 7 KARIN TOMALA, Kulturspezifische Barrieren in der chinesischen Bevölkerungspolitik ....................................................................................... 23 LEE M I N G-H U E I, Culture et démocratie: réflexions à partir de la polémique entre libéraux taiwanais et néo-confucéens contemporains ......................... 65 £UKASZ -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Shot in Shanghai: Sino

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Shot in Shanghai: Sino‐U.S. Media Co‐Production in the Post‐WTO Era A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Asian Languages and Cultures by Aynne Elizabeth Kokas 2012 © Copyright by Aynne Elizabeth Kokas 2012 UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Shot in Shanghai: Sino‐U.S. Media Co‐Production in the Post‐WTO Era by Aynne Elizabeth Kokas Doctor of Philosophy in Asian Languages and Cultures University of California, Los Angeles, 2012 Professor Theodore Huters, Co‐Chair Professor John Caldwell, Co‐Chair “Shot in Shanghai” examines Sino-U.S. media co-production to reveal the complex negotiation between transnational commercial interests, state regulation of media, and the reform of the Chinese state-run film industry. By situating the study in the commercial center of Shanghai, the dissertation argues that the transformation of media industries exists as part of a delicate compromise between China’s hexie shehui (harmonious society—a euphemistic explanation for government control of media content) and the forces of global capital. To form a foundation for future scholarship in the fields of media studies and Chinese studies, the dissertation articulates the complexity of film co-production in the ten years between China’s accession to the WTO and the PRC’s 2011 twelfth five year plan. The dissertation introduces three central concepts that are crucial to understanding the growth of media collaboration between China and the U.S. These include the role of ii the urban brand, the importance of latter day compradors (maiban), and the growth of global production ecosystems in the PRC. -

China Railway Technologies Study Tour

China Railway Technologies Study Tour BUSINESS BRIEFING Thursday, May 23, 2019 • 9:30 A.M.–4:30 P.M. Hyatt Centric Magnificent Mile Hotel • Chicago, IL CONNECT WITH USTDA AGENDA China Rail Technologies Study Tour Business Briefing to U.S. Industry Hosted by the U.S. Trade and Development Agency (USTDA) Thursday, May 23, 2019 ____________________________________________________________________ 9:30 - 10:00 a.m. Registration - Lakeshore Ballroom (3rd floor) 9:55 - 10:00 a.m. Administrative Remarks – KEA 10:00 - 10:10 a.m. Welcome and USTDA Overview by Ms. Alissa Lee - Country Manager for East Asia and the Indo-Pacific - USTDA 10:10 - 10:20 a.m. Comments by Mr. Dan Kim - Senior International Trade Specialist - U.S. Commercial Service, Chicago 10:20 - 10:30 a.m. Introduction of American Rail Working Group (ARWG) by Ms. Ida Peng, Senior Commercial Specialist, U.S. Embassy Beijing 10:30 a.m. - 12:05 p.m. Delegate Presentations 10:30 - 11:00 a.m. Presentation by Mr. Zhang Dayong - Deputy Director-General, Locomotive & Car Department, China Railway (CR) 11:00 - 11:10 a.m. Questions and Answers 11:10 - 11:25 a.m. Tea/Coffee Break 11:25 - 11:55 a.m. Presentation by CR 11:55 a.m. - 12:05 p.m. Questions and Answers 12:05 - 12:30 p.m. Introduction of Delegates 12:30 - 12:40 p.m. Introduction of U.S. Participants 12:45 - 1:45 p.m. Networking Luncheon - St. Clair Ballroom 2:00 - 4:00 p.m. One-on-One Meetings between Chinese delegates and U.S. Industry Representatives - Lakeshore Ballroom 4:30 p.m. -

To View China Railway 2019 Annual Report, Please Click Here

(a joint stock limited company incorporated in the People's Republic of China with limited liability) Stock Code : 390 Annual Report 2019 CONTENTS Company Profile 1 Financial Summary 2 Chairman’s Report 4 Changes in Share Capital and Information on Shareholders 7 Business Overview 17 Management Discussion and Analysis 34 Biography of Directors, Supervisors and Senior Management 47 Report of the Directors 59 Report on Corporate Governance Practices 76 Independent Auditor’s Report 97 Financial Statements 103 Significant Events 273 Definition and Glossary of Technical Terms 309 Company Information 311 2019 ANNUAL REPORT CHINA RAILWAY GROUP LIMITED COMPANY PROFILE 1 The Company was established as a joint stock company with limited liability in the People’s Republic of China (the “PRC”) under the Company Law of the PRC on 12 September 2007. The A shares and H shares issued by the Company were listed on the Shanghai Stock Exchange and the main board of The Stock Exchange of Hong Kong Limited (the “Hong Kong Stock Exchange”) on 3 December 2007 and 7 December 2007 respectively. We are one of the largest multi-functional integrated construction group in the PRC and Asia in terms of the total revenue of the engineering contract, and rank 55th on the 2019 Fortune Global 500 list. We offer a full range of construction-related services, including infrastructure construction, survey, design and consulting services and engineering equipment and component manufacturing, and also expand to property development and other businesses such as mining. We have outstanding advantages in the construction of infrastructure facilities such as railways, highways, municipal works and urban rails. -

China Makes, the World Takes

The Atlantic Monthly | July/August 2007 CHINA MAKES, THE WORLD TAKES A look inside the world’s manufacturing center shows that America should welcome China’s rise—for now. BY JAMES FALLOWS ..... CONTAINERS READY FOR SHIPMENT from the port of Shenzhen Photos by Michael Christopher Brown From Atlantic Unbound: Slideshow: "Made in China" James Fallows narrates photos from the heart of the Chinese manufacturing dynamo. Half the time I have spent in China I have spent in factories. At least that’s how it feels—and it’s a feeling I sought. The factories where more than 100 million Chinese men and women toil, and from which cameras, clothes, and every other sort of ware flow out to the world, are to me the most startling and intense aspect of today’s China. For now, they are also the most important. They are startling above all in their scale. I was prepared for the skyline of Shanghai and its 240-mph Maglev train to the airport, and for the nonstop construction, dust, and bustle of Beijing. Every account of modern China mentions them. But I had no concept of the sweep of what has become the world’s manufacturing center: the Pearl River Delta of Guangdong province (the old Canton region), just north of Hong Kong. That one province might have a manufacturing workforce larger than America’s. Statistics from China are largely guesses, but Guangdong’s population is around 90 million. If even one-fifth of its people hold manufacturing jobs, as seems likely in big cities, that would be 18 million—versus 14 million in the entire United States. -

Axalta Paints China's New Bullet Train Model Fuxing

NEWS RELEASE Axalta Paints China’s New Bullet Train Model Fuxing 7/5/2017 Axalta coats new generation CR400AF bullet trains with durable coatings that support longer service lifespan SHANGHAI--(BUSINESS WIRE)-- Axalta Coating Systems (NYSE: AXTA), a leading global liquid and powder coatings supplier, coats China's new Fuxing model bullet train in collaboration with CRRC Qingdao Sifang Co., Ltd. A CR400AF model with Axalta’s bright red Imron™ coatings along its beltlines departed from Beijing South Railway Station to Shanghai on June 27, welcoming a milestone in China’s high-speed railway system. This Smart News Release features multimedia. View the full release here: http://www.businesswire.com/news/home/20170705005586/en/ Axalta’s Imron dazzles on China’s new super high-speed Fuxing bullet train between Shanghai As China’s next generation high and Beijing. (Photo: Axalta) speed trian, the Fuxing, which means “rejuvenation” in Chinese, is designed to cruise at 350 kilometers per hour and reach a maximum of 400 km/h, which doubles the speed of its predecessor Hexie train. The Fuxing train is designed to last for 30 years, which is 10 years longer than that of the Hexie train. It also has been constructed to meet China’s latest rigorous environmental, safety, and passenger comfort performance standards. Partnering with CRRC Qingdao Sifang Co., Ltd, the world's largest supplier of rail transit equipment, Axalta provided a comprehensive portfolio of surfacer, primer, base coat and clearcoat to meet the Fuxing’s tough operating environments and high speed demands. The outstanding weatherability characteristics of Axalta’s products will provide the trains with 1,500 hours of resistance to aging, significantly upgrading the lifespan of the painted exterior of the Fuxing. -

A Neo-Schumpeterian Analysis Hing Lee Henry CHAN Singapore Management University, [email protected]

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Institutional Knowledge at Singapore Management University Singapore Management University Institutional Knowledge at Singapore Management University Dissertations and Theses Collection Dissertations and Theses 11-2016 Evaluating the conditions for China’s 4th Industrial Revolution plan: A neo-Schumpeterian analysis Hing Lee Henry CHAN Singapore Management University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ink.library.smu.edu.sg/etd_coll_all Part of the Asian Studies Commons, and the International Economics Commons Citation CHAN, Hing Lee Henry. Evaluating the conditions for China’s 4th Industrial Revolution plan: A neo-Schumpeterian analysis. (2016). 1-185. Dissertations and Theses Collection. Available at: https://ink.library.smu.edu.sg/etd_coll_all/8 This PhD Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Dissertations and Theses at Institutional Knowledge at Singapore Management University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses Collection by an authorized administrator of Institutional Knowledge at Singapore Management University. For more information, please email [email protected]. EVALUATING THE CONDITIONS FOR CHINA’S 4TH INDUSTRIAL REVOLUTION PLAN: A NEO-SCHUMPETERIAN ANALYSIS CHAN HING LEE HENRY SINGAPORE MANAGEMENT UNIVERSITY 2016 Evaluating the conditions for China’s 4th Industrial Revolution Plan: A neo-Schumpeterian Analysis by Chan Hing Lee Henry Submitted -

Heading Off Track: the Impact of China's Mercantilist

TwitterFacebookLinkedInYoutube ISSUES REGIONS PUBLICATIONS EVENTS NEWS ROOM ABOUT DONATE Heading Off Track: The Impact of China’s Mercantilist Policies on Global High-Speed Rail Innovation By Nigel Cory April 26, 2021 Downloads Chinese high-speed rail firm CRRC is less innovative than European and Japanese firms, but mercantilist policies help it dominate in China and expand globally. This starves superior firms of revenue, reduces their R&D, and slows the pace of global innovation. CONTENTS KEY TAKEAWAYS Introduction China’s state-directed bid for a leadership position in the high-speed rail sector has distorted the global market with massive subsidization, High-Speed Rail mandated mergers, forced technology transfers, and other mercantilist Technology and Innovation: The Past practices. and Future With its vast resources, China could have financed win-win trade and The Competition innovation. Instead, it pursued zero-sum mercantilism, closing its own Between China, the market and subsidizing its rail firms to help them take advantage of open EU, Japan, and the foreign markets. United States for Global Rail Production and Exports There are only a few large high-speed rail projects at any one time worldwide. It’s critical that they go to market- and innovation-driven firms, China’s Mercantilist not state-driven players like CRRC. Toolbox for High- Speed Rail CRRC is already working on high-speed projects in developing countries, and with its state backing it is now tirelessly pursuing its first big prize in a China’s High-Speed Rail Mercantilism developed country. Goes Global The huge diversion of global market share and revenue to CRRC has helped Testing the it catch up to its competitors. -

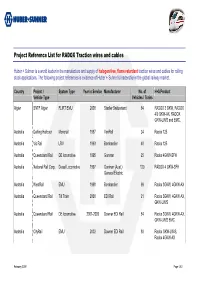

Project Reference List for RADOX Traction Wires and Cables

Project Reference List for RADOX Traction wires and cables Huber + Suhner is a world leader in the manufacture and supply of halogen free, flame retardant traction wires and cables for rolling stock applications. The following project references is evidence of Huber + Suhner’s leadership in the global railway market. Country Project / System Type Year in Service Manufacturer No. of H+S Product Vehicle Type Vehicles / Trains Algier SNTF Algier FLIRT EMU 2008 Stadler Switzerland 64 RADOX 3 GKW, RADOX 4/9 GKW-AX, RADOX GKW-LW/S and EMC, Australia Darling Harbour Monorail 1987 VonRoll 24 Radox 125 Australia Vic Rail LRV 1993 Bombardier 40 Radox 125 Australia Queensland Rail DE locomotive 1995 Goninan 25 Radox 4GKW-SFH Australia National Rail Corp. Diesel Locomotive 1997 Goninan (Aust.) 120 RADOX 4 GKW-SFH General Electric Australia WestRail EMU 1998 Bombardier 99 Radox 3GKW, 4GKW-AX Australia Queensland Rail Tilt Train 2000 EDI Rail 21 Radox 3GKW, 4GKW-AX, GKW-LW/S Australia Queensland Rail DE locomotive 2001-2009 Downer EDI Rail 84 Radox 3GKW, 4GKW-AX, GKW-LW/S EMC Australia CityRail EMU 2002 Downer EDI Rail 80 Radox GKW-LW/S, Radox 4GKW-AX February 2009 Page 1/40 Country Project / System Type Year in Service Manufacturer No. of H+S Product Vehicle Type Vehicles / Trains Australia RailCorp / EMU 2002-2005 Downer EDI Rail 140 Radox 3GKW, 4GKW-AX, Millennium GKW-LW/S EMC. Databus Australia RailCorp / Hunter DMU 2003-2005 United Goninan 21 Radox 3GKW, 4GKW-AX, Valley GKW-LW/S EMC Australia RailCorp EMU 2004 United Goninan 60 Radox 3GKW, 4GKW-AX,