Established Conditions List

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Approach to a Case of Congenital Heart Disease

BAI JERBAI WADIA HOSPITAL FOR CHILDREN PEDIATRIC CLINICS FOR POST GRADUATES PREFACE This book is a compilation of the discussions carried out at the course for post-graduates on ” Clinical Practical Pediatrics” at the Bai Jerbai Wadia Hospital for Children, Mumbai. It has been prepared by the teaching faculty of the course and will be a ready-reckoner for the exam-going participants. This manual covers the most commonly asked cases in Pediatric Practical examinations in our country and we hope that it will help the students in their practical examinations. An appropriately taken history, properly elicited clinical signs, logical diagnosis with the differential diagnosis and sound management principles definitely give the examiner the feeling that the candidate is fit to be a consultant of tomorrow. Wishing you all the very best for your forthcoming examinations. Dr.N.C.Joshi Dr.S.S.Prabhu Program Directors. FOREWARD I am very happy to say that the hospital has taken an initiative to organize this CME for the postgraduate students. The hospital is completing 75 years of its existence and has 2 done marvelous work in providing excellent sevices to the children belonging to the poor society of Mumbai and the country. The hospital gets cases referred from all over the country and I am proud to say that the referrals has stood the confidence imposed on the hospital and its faculty. We do get even the rarest of the rare cases which get diagnosed and treated. I am sure all of you will be immensely benefited by this programme. Wish you all the best in your examination and career. -

Basilar Artery and Its Branches Called Pontine Arteries

3 Farah Mohammad Ahmad Al-Tarefe Mohammad Al salem تذكر أ َّن : أولئك الذين بداخلهم شيء يفوق كل الظروف ، هم فقط من استطاعوا أ ّن يحققوا انجازاً رائعاً .... كن ذا همة Recommendation: Study this sheet after you finish the whole anatomy material . Dr.Alsalem started talking about the blood supply for brain and spinal cord which are mentioned in sheet#5 so that we didn't write them . 26:00-56:27/ Rec.Lab#3 Let start : Medulla oblengata : we will study the blood supply in two levels . A- Close medulla (central canal) : It is divided into four regions ; medial , anteromedial , posteriolateral and posterior region. Medially : anterior spinal artery. Anteromedial: vertebral artery posterolateral : posterior inferior cerebellar artery ( PICA). Posterior : posterior spinal artery which is a branch from PICA. B-Open medulla ( 4th ventricle ) : It is divided into four regions ; medial , anteromedial , posteriolateral region. Medially : anterior spinal artery. Anteromedial: vertebral artery posterolateral : posterior inferior cerebellar artery ( PICA). 1 | P a g e Lesions: 1- Medial medullary syndrome (Dejerine syndrome): It is caused by a lesion in anterior spinal artery which supplies the area close to the mid line. Symptoms: (keep your eyes on right pic). Contralateral hemiparesis= weakness: the pyramid will be affected . Contralateral loss of proprioception , fine touch and vibration (medial lemniscus). Deviation of the tongue to the ipsilateral side when it is protruded (hypoglossal root or nucleus injury). This syndrome is characterized by Alternating hemiplegia MRI from Open Medulla (notice the 4th ventricle) Note :The Alternating hemiplegia means ; 1- The upper and lower limbs are paralyzed in the contralateral side of lesion = upper motor neuron lesion . -

Advances in Understanding the Genetics of Syndromes Involving Congenital Upper Limb Anomalies

Review Article Page 1 of 10 Advances in understanding the genetics of syndromes involving congenital upper limb anomalies Liying Sun1#, Yingzhao Huang2,3,4#, Sen Zhao2,3,4, Wenyao Zhong1, Mao Lin2,3,4, Yang Guo1, Yuehan Yin1, Nan Wu2,3,4, Zhihong Wu2,3,5, Wen Tian1 1Hand Surgery Department, Beijing Jishuitan Hospital, Beijing 100035, China; 2Beijing Key Laboratory for Genetic Research of Skeletal Deformity, Beijing 100730, China; 3Medical Research Center of Orthopedics, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences, Beijing 100730, China; 4Department of Orthopedic Surgery, 5Department of Central Laboratory, Peking Union Medical College Hospital, Peking Union Medical College and Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences, Beijing 100730, China Contributions: (I) Conception and design: W Tian, N Wu, Z Wu, S Zhong; (II) Administrative support: All authors; (III) Provision of study materials or patients: All authors; (IV) Collection and assembly of data: Y Huang; (V) Data analysis and interpretation: L Sun; (VI) Manuscript writing: All authors; (VII) Final approval of manuscript: All authors. Correspondence to: Wen Tian. Hand Surgery Department, Beijing Jishuitan Hospital, Beijing 100035, China. Email: [email protected]. Abstract: Congenital upper limb anomalies (CULA) are a common birth defect and a significant portion of complicated syndromic anomalies have upper limb involvement. Mostly the mortality of babies with CULA can be attributed to associated anomalies. The cause of the majority of syndromic CULA was unknown until recently. Advances in genetic and genomic technologies have unraveled the genetic basis of many syndromes- associated CULA, while at the same time highlighting the extreme heterogeneity in CULA genetics. Discoveries regarding biological pathways and syndromic CULA provide insights into the limb development and bring a better understanding of the pathogenesis of CULA. -

Practitioners' Section

407 408 GENETICS OF MENTAL RETARDATION [2] [4] PRACTITIONERS’ SECTION epiphenomena. A specific cause for mental a group heritability of 0.49. The aetiology of retardation can be identified in approximately idiopathic mental retardation is usually 80% of people with SMR (IQ<50) and 50% of explained in terms of the ‘polygenic GENETICS OF MENTAL RETARDATION people with MMR (IQ 50–70). multifactorial model.’ The difficulty is that there A. S. AHUJA, ANITA THAPAR, M. J. OWEN are too few studies to provide sufficiently In this article, we will begin by considering precise estimates of the likely role of genes ABSTRACT what is known about the genetics of idiopathic and environment in determining idiopathic mental retardation and then move onto discuss mental retardation. Given the dearth of Mental retardation can follow any of the biological, environmental and psychological events that are capable of producing deficits in cognitive functions. specific genetic causes of mental retardation. published literature we are reliant on Recent advances in molecular genetic techniques have enabled us to understand attempting to draw conclusions from family and more about the molecular basis of several genetic syndromes associated with mental Search methodology twin studies, most of which are very old and retardation. In contrast, where there is no discrete cause, the interplay of genetic Electronic searching was done and the which report widely varying recurrence risks.[5] and environmental influences remains poorly understood. This article presents a relevant studies were identified by searching Recent studies of MMR have shown high rates critical review of literature on genetics of mental retardation. -

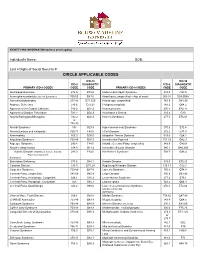

Circle Applicable Codes

IDENTIFYING INFORMATION (please print legibly) Individual’s Name: DOB: Last 4 Digits of Social Security #: CIRCLE APPLICABLE CODES ICD-10 ICD-10 ICD-9 DIAGNOSTIC ICD-9 DIAGNOSTIC PRIMARY ICD-9 CODES CODE CODE PRIMARY ICD-9 CODES CODE CODE Abetalipoproteinemia 272.5 E78.6 Hallervorden-Spatz Syndrome 333.0 G23.0 Acrocephalosyndactyly (Apert’s Syndrome) 755.55 Q87.0 Head Injury, unspecified – Age of onset: 959.01 S09.90XA Adrenaleukodystrophy 277.86 E71.529 Hemiplegia, unspecified 342.9 G81.90 Arginase Deficiency 270.6 E72.21 Holoprosencephaly 742.2 Q04.2 Agenesis of the Corpus Callosum 742.2 Q04.3 Homocystinuria 270.4 E72.11 Agenesis of Septum Pellucidum 742.2 Q04.3 Huntington’s Chorea 333.4 G10 Argyria/Pachygyria/Microgyria 742.2 Q04.3 Hurler’s Syndrome 277.5 E76.01 or 758.33 Aicardi Syndrome 333 G23.8 Hyperammonemia Syndrome 270.6 E72.4 Alcohol Embryo and Fetopathy 760.71 F84.5 I-Cell Disease 272.2 E77.0 Anencephaly 655.0 Q00.0 Idiopathic Torsion Dystonia 333.6 G24.1 Angelman Syndrome 759.89 Q93.5 Incontinentia Pigmenti 757.33 Q82.3 Asperger Syndrome 299.8 F84.5 Infantile Cerebral Palsy, unspecified 343.9 G80.9 Ataxia-Telangiectasia 334.8 G11.3 Intractable Seizure Disorder 345.1 G40.309 Autistic Disorder (Childhood Autism, Infantile 299.0 F84.0 Klinefelter’s Syndrome 758.7 Q98.4 Psychosis, Kanner’s Syndrome) Biotinidase Deficiency 277.6 D84.1 Krabbe Disease 333.0 E75.23 Canavan Disease 330.0 E75.29 Kugelberg-Welander Disease 335.11 G12.1 Carpenter Syndrome 759.89 Q87.0 Larsen’s Syndrome 755.8 Q74.8 Cerebral Palsy, unspecified 343.69 G80.9 -

2018 Etiologies by Frequencies

2018 Etiologies in Order of Frequency by Category Hereditary Syndromes and Disorders Count CHARGE Syndrome 958 Down syndrome (Trisomy 21 syndrome) 308 Usher I syndrome 252 Stickler syndrome 130 Dandy Walker syndrome 119 Cornelia de Lange 102 Goldenhar syndrome 98 Usher II syndrome 83 Wolf-Hirschhorn syndrome (Trisomy 4p) 68 Trisomy 13 (Trisomy 13-15, Patau syndrome) 60 Pierre-Robin syndrome 57 Moebius syndrome 55 Trisomy 18 (Edwards syndrome) 52 Norrie disease 38 Leber congenital amaurosis 35 Chromosome 18, Ring 18 31 Aicardi syndrome 29 Alstrom syndrome 27 Pfieffer syndrome 27 Treacher Collins syndrome 27 Waardenburg syndrome 27 Marshall syndrome 25 Refsum syndrome 21 Cri du chat syndrome (Chromosome 5p- synd) 16 Bardet-Biedl syndrome (Laurence Moon-Biedl) 15 Hurler syndrome (MPS I-H) 15 Crouzon syndrome (Craniofacial Dysotosis) 13 NF1 - Neurofibromatosis (von Recklinghausen dis) 13 Kniest Dysplasia 12 Turner syndrome 11 Usher III syndrome 10 Cockayne syndrome 9 Apert syndrome/Acrocephalosyndactyly, Type 1 8 Leigh Disease 8 Alport syndrome 6 Monosomy 10p 6 NF2 - Bilateral Acoustic Neurofibromatosis 6 Batten disease 5 Kearns-Sayre syndrome 5 Klippel-Feil sequence 5 Hereditary Syndromes and Disorders Count Prader-Willi 5 Sturge-Weber syndrome 5 Marfan syndrome 3 Hand-Schuller-Christian (Histiocytosis X) 2 Hunter Syndrome (MPS II) 2 Maroteaux-Lamy syndrome (MPS VI) 2 Morquio syndrome (MPS IV-B) 2 Optico-Cochleo-Dentate Degeneration 2 Smith-Lemli-Opitz (SLO) syndrome 2 Wildervanck syndrome 2 Herpes-Zoster (or Hunt) 1 Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada -

Pyrexia of Unknown Origin. Presenting Sign of Hypothalamic Hypopituitarism R

Postgrad Med J: first published as 10.1136/pgmj.57.667.310 on 1 May 1981. Downloaded from Postgraduate Medical Journal (May 1981) 57, 310-313 Pyrexia of unknown origin. Presenting sign of hypothalamic hypopituitarism R. MARILUS* A. BARKAN* M.D. M.D. S. LEIBAt R. ARIE* M.D. M.D. I. BLUM* M.D. *Department of Internal Medicine 'B' and tDepartment ofEndocrinology, Beilinson Medical Center, Petah Tiqva, The Sackler School of Medicine, Tel Aviv University, Ramat Aviv, Israel Summary least 10 such admissions because offever of unknown A 62-year-old man was admitted to hospital 10 times origin had been recorded. During this period, he over 12 years because of pyrexia of unknown origin. was extensively investigated for possible infectious, Hypothalamic hypopituitarism was diagnosed by neoplastic, inflammatory and collagen diseases, but dynamic tests including clomiphene, LRH, TRH and the various tests failed to reveal the cause of theby copyright. chlorpromazine stimulation. Lack of ACTH was fever. demonstrated by long and short tetracosactrin tests. A detailed past history of the patient was non- The aetiology of the disorder was believed to be contributory. However, further questioning at a previous encephalitis. later period of his admission revealed interesting Following substitution therapy with adrenal and pertinent facts. Twelve years before the present gonadal steroids there were no further episodes of admission his body hair and sex activity had been fever. normal. At that time he had an acute febrile illness with severe headache which lasted for about one Introduction week. He was not admitted to hospital and did not http://pmj.bmj.com/ Pyrexia of unknown origin (PUO) may present receive any specific therapy. -

Megalencephaly and Macrocephaly

277 Megalencephaly and Macrocephaly KellenD.Winden,MD,PhD1 Christopher J. Yuskaitis, MD, PhD1 Annapurna Poduri, MD, MPH2 1 Department of Neurology, Boston Children’s Hospital, Boston, Address for correspondence Annapurna Poduri, Epilepsy Genetics Massachusetts Program, Division of Epilepsy and Clinical Electrophysiology, 2 Epilepsy Genetics Program, Division of Epilepsy and Clinical Department of Neurology, Fegan 9, Boston Children’s Hospital, 300 Electrophysiology, Department of Neurology, Boston Children’s Longwood Avenue, Boston, MA 02115 Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts (e-mail: [email protected]). Semin Neurol 2015;35:277–287. Abstract Megalencephaly is a developmental disorder characterized by brain overgrowth secondary to increased size and/or numbers of neurons and glia. These disorders can be divided into metabolic and developmental categories based on their molecular etiologies. Metabolic megalencephalies are mostly caused by genetic defects in cellular metabolism, whereas developmental megalencephalies have recently been shown to be caused by alterations in signaling pathways that regulate neuronal replication, growth, and migration. These disorders often lead to epilepsy, developmental disabilities, and Keywords behavioral problems; specific disorders have associations with overgrowth or abnor- ► megalencephaly malities in other tissues. The molecular underpinnings of many of these disorders are ► hemimegalencephaly now understood, providing insight into how dysregulation of critical pathways leads to ► -

Saethre-Chotzen Syndrome

Saethre-Chotzen syndrome Authors: Professor L. Clauser1 and Doctor M. Galié Creation Date: June 2002 Update: July 2004 Scientific Editor: Professor Raoul CM. Hennekam 1Department of craniomaxillofacial surgery, St. Anna Hospital and University, Corso Giovecca, 203, 44100 Ferrara, Italy. [email protected] Abstract Keywords Disease name and synonyms Excluded diseases Definition Prevalence Management including treatment Etiology Diagnostic methods Genetic counseling Antenatal diagnosis Unresolved questions References Abstract Saethre-Chotzen Syndrome (SCS) is an inherited craniosynostotic condition, with both premature fusion of cranial sutures (craniostenosis) and limb abnormalities. The most common clinical features, present in more than a third of patients, consist of coronal synostosis, brachycephaly, low frontal hairline, facial asymmetry, hypertelorism, broad halluces, and clinodactyly. The estimated birth incidence is 1/25,000 to 1/50,000 but because the phenotype can be very mild, the entity is likely to be underdiagnosed. SCS is inherited as an autosomal dominant trait with a high penetrance and variable expression. The TWIST gene located at chromosome 7p21-p22, is responsible for SCS and encodes a transcription factor regulating head mesenchyme cell development during cranial tube formation. Some patients with an overlapping SCS phenotype have mutations in the FGFR3 (fibroblast growth factor receptor 3) gene; especially the Pro250Arg mutation in FGFR3 (Muenke syndrome) can resemble SCS to a great extent. Significant intrafamilial -

The Genetic Heterogeneity of Brachydactyly Type A1: Identifying the Molecular Pathways

The genetic heterogeneity of brachydactyly type A1: Identifying the molecular pathways Lemuel Jean Racacho Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Postdoctoral Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctorate in Philosophy degree in Biochemistry Specialization in Human and Molecular Genetics Department of Biochemistry, Microbiology and Immunology Faculty of Medicine University of Ottawa © Lemuel Jean Racacho, Ottawa, Canada, 2015 Abstract Brachydactyly type A1 (BDA1) is a rare autosomal dominant trait characterized by the shortening of the middle phalanges of digits 2-5 and of the proximal phalange of digit 1 in both hands and feet. Many of the brachymesophalangies including BDA1 have been associated with genetic perturbations along the BMP-SMAD signaling pathway. The goal of this thesis is to identify the molecular pathways that are associated with the BDA1 phenotype through the genetic assessment of BDA1-affected families. We identified four missense mutations that are clustered with other reported BDA1 mutations in the central region of the N-terminal signaling peptide of IHH. We also identified a missense mutation in GDF5 cosegregating with a semi-dominant form of BDA1. In two families we reported two novel BDA1-associated sequence variants in BMPR1B, the gene which codes for the receptor of GDF5. In 2002, we reported a BDA1 trait linked to chromosome 5p13.3 in a Canadian kindred (BDA1B; MIM %607004) but we did not discover a BDA1-causal variant in any of the protein coding genes within the 2.8 Mb critical region. To provide a higher sensitivity of detection, we performed a targeted enrichment of the BDA1B locus followed by high-throughput sequencing. -

MEDICAL GENETICS RESIDENCY PROGRAM Department of Pediatrics

MEDICAL GENETICS RESIDENCY PROGRAM Department of Pediatrics University of Michigan Health Systems (734) 763-6767 1500 E. Medical Center Drive (734) 763-6561 (fax) D5240 MPB Ann Arbor, MI 48109-5718 Biochemical Genetics Goals and Objectives Director: Drs. Ayesha Ahmad and Shane C. Quinonez The goals and objectives of the Biochemical Genetics Clinic rotation in the Medical Genetics Residency Program are to provide the resident with exposure to all aspects of care of metabolic disease and counseling in accordance with the Residency Review Committee for Medical Genetics expectations and to fulfill criteria for board eligibility by the American Board of Medical Genetics. Patient Care The resident will become familiar with the evaluation, diagnosis and management of urea cycle disorders, organic acidemias, disorders of carbohydrate and lipid metabolism and numerous other inborn errors of metabolism (IEMs). Residents will gain exposure in performing and expertise in interpreting biochemical analyses relevant to the diagnosis and management of human genetic diseases. By the end of the rotation the resident should be able to identify signs and symptoms of IEMs, formulate a differential diagnosis, order appropriate tests and recognize normal variants and complex patterns of metabolites. Residents will be able to manage acute metabolic crises and provide chronic management of patients with an IEM. Residents should be able to interpret NBS results, collaborate with the primary provider to act upon results in a timely manner, develop a differential diagnosis and order appropriate confirmatory testing and communicate results to families. Medical Knowledge Through coursework and didactic sessions with attending physicians, residents will become familiar with fundamental concepts, molecular biology and biochemistry relevant to IEMs. -

Level Estimates of Maternal Smoking and Nicotine Replacement Therapy During Pregnancy

Using primary care data to assess population- level estimates of maternal smoking and nicotine replacement therapy during pregnancy Nafeesa Nooruddin Dhalwani BSc MSc Thesis submitted to the University of Nottingham for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy November 2014 ABSTRACT Background: Smoking in pregnancy is the most significant preventable cause of poor health outcomes for women and their babies and, therefore, is a major public health concern. In the UK there is a wide range of interventions and support for pregnant women who want to quit. One of these is nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) which has been widely available for retail purchase and prescribing to pregnant women since 2005. However, measures of NRT prescribing in pregnant women are scarce. These measures are vital to assess its usefulness in smoking cessation during pregnancy at a population level. Furthermore, evidence of NRT safety in pregnancy for the mother and child’s health so far is nebulous, with existing studies being small or using retrospectively reported exposures. Aims and Objectives: The main aim of this work was to assess population- level estimates of maternal smoking and NRT prescribing in pregnancy and the safety of NRT for both the mother and the child in the UK. Currently, the only population-level data on UK maternal smoking are from repeated cross-sectional surveys or routinely collected maternity data during pregnancy or at delivery. These obtain information at one point in time, and there are no population-level data on NRT use available. As a novel approach, therefore, this thesis used the routinely collected primary care data that are currently available for approximately 6% of the UK population and provide longitudinal/prospectively recorded information throughout pregnancy.