Volume 5.1 New

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NIER's Rejection of the Heteronormative in Fairy

Cerri !1 “This Is Hardly the Happy Ending I Was Expecting”: NIER’s Rejection of the Heteronormative in Fairy Tales Video games are popularly viewed as a form of escapist entertainment with no real meaning or message. They are often considered as unnecessarily violent forms of recreation that possibly incite aggressive tendencies in their players. Overall, they are generally condemned as having no value. However, these beliefs are fallacious, as there is enormous potential in video games as not just learning tools but also as a source of literary criticism. Games have the capacity to generate criticisms that challenge established narratives through content and form. Thus, video games should be viewed as a new medium that demands serious analysis. Furthermore, the analysis generated by video games can benefit from being read through existing literary forms of critique. For example, the game NIER (2010, Cavia) can be read through a critical lens to evaluate its use of the fairy tale genre. More specifically, NIER can be analyzed using queer theory for the game’s reimagining and queering of the fairy tale genre. Queer theory, which grew prominent in the 1990s, is a critical theory that proposes a new way to approach identity and normativity. It distinguishes gender from biological sex, deconstructs the notion of gender as a male-female binary, and addresses the importance of performance in gender identification. That is, historically and culturally assigned mannerisms establish gender identity, and in order to present oneself with a certain gender one must align their actions with the expected mannerisms of that history and culture. -

Fairy Tale Females: What Three Disney Classics Tell Us About Women

FFAAIIRRYY TTAALLEE FFEEMMAALLEESS:: WHAT THREE DISNEY CLASSICS TELL US ABOUT WOMEN Spring 2002 Debbie Mead http://members.aol.com/_ht_a/ vltdisney?snow.html?mtbrand =AOL_US www.kstrom.net/isk/poca/pocahont .html www_unix.oit.umass.edu/~juls tar/Cinderella/disney.html Spring 2002 HCOM 475 CAPSTONE Instructor: Dr. Paul Fotsch Advisor: Professor Frances Payne Adler FAIRY TALE FEMALES: WHAT THREE DISNEY CLASSICS TELL US ABOUT WOMEN Debbie Mead DEDICATION To: Joel, whose arrival made the need for critical viewing of media products more crucial, Oliver, who reminded me to be ever vigilant when, after viewing a classic Christmas video from my youth, said, “Way to show me stereotypes, Mom!” Larry, who is not a Prince, but is better—a Partner. Thank you for your support, tolerance, and love. TABLE OF CONTENTS Once Upon a Time --------------------------------------------1 The Origin of Fairy Tales ---------------------------------------1 Fairy Tale/Legend versus Disney Story SNOW WHITE ---------------------------------------------2 CINDERELLA ----------------------------------------------5 POCAHONTAS -------------------------------------------6 Film Release Dates and Analysis of Historical Influence Snow White ----------------------------------------------8 Cinderella -----------------------------------------------9 Pocahontas --------------------------------------------12 Messages Beauty --------------------------------------------------13 Relationships with other women ----------------------19 Relationships with men --------------------------------21 -

Snow White & Rose

Penguin Young Readers Factsheets Level 2 Snow White Teacher’s Notes and Rose Red Summary of the story Snow White and Rose Red is the story of two sisters who live with their mother in the forest. One cold winter day a bear comes to their house to shelter, and they give him food and drink. Later, in the spring, the girls are in the forest, and they see a dwarf whose beard is stuck under a tree. The girls cut his beard to free him, but he is not grateful. Some days after, they see the dwarf attacked by a large bird and again rescue him. Next, they see the dwarf with treasure. He tells the bear that they are thieves. The bear recognizes the sisters and scares the dwarf away. After hugging the sisters, he turns into a prince. The girls go to his castle, marry the prince and his brother and their mother joins them. About the author The story was first written down by Charles Perrault in the mid seventeenth century. Then it was popularized by the Grimm brothers, Jacob Ludwig Karl Grimm, 1785-1863, and Wilhelm Karl Grimm, 1786-1859. They were both professors of German literature and librarians at the University of Gottingen who collected and wrote folk tales. Topics and themes Animals. How big are bears? How strong are they? Encourage the pupils to research different types of bears. Look at their habitat, eating habits, lives. Collect pictures of them. Fairy tales. Several aspects from this story could be taken up. Feelings. The characters in the story go through several emotions: fear, (pages 1,10) anger, (page 5) surprise (page 11). -

Tracing Fairy Tales in Popular Culture Through the Depiction of Maternity in Three “Snow White” Variants

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository College of Arts & Sciences Senior Honors Theses College of Arts & Sciences 5-2014 Reflective tales : tracing fairy tales in popular culture through the depiction of maternity in three “Snow White” variants. Alexandra O'Keefe University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/honors Part of the Children's and Young Adult Literature Commons, and the Comparative Literature Commons Recommended Citation O'Keefe, Alexandra, "Reflective tales : tracing fairy tales in popular culture through the depiction of maternity in three “Snow White” variants." (2014). College of Arts & Sciences Senior Honors Theses. Paper 62. http://doi.org/10.18297/honors/62 This Senior Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Arts & Sciences at ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in College of Arts & Sciences Senior Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. O’Keefe 1 Reflective Tales: Tracing Fairy Tales in Popular Culture through the Depiction of Maternity in Three “Snow White” Variants By Alexandra O’Keefe Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Graduation summa cum laude University of Louisville March, 2014 O’Keefe 2 The ability to adapt to the culture they occupy as well as the two-dimensionality of literary fairy tales allows them to relate to readers on a more meaningful level. -

Snow White’’ Tells How a Parent—The Queen—Gets Destroyed by Jealousy of Her Child Who, in Growing Up, Surpasses Her

WARNING Concerning Copyright Restrictions The copyright law of the United States (Title 1.7, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. Under certain conditions specified in the law, libraries and archives are authorized to furnish a photocopy or reproduction. One of three specified conditions is that the photocopy or reproduction is not to be used for any purpose other than private study, scholarship or research. If electronic transmission of reserve material is used for purposes in excess of what constitutes “fair use”, that user may be liable for copyright infringement. This policy is in effect for the following document: Fear of Fantasy 117 people. They do not realize that fairy tales do not try to describe the external world and “reality.” Nor do they recognize that no sane child ever believes that these tales describe the world realistically. Some parents fear that by telling their children about the fantastic events found in fairy tales, they are “lying” to them. Their concern is fed by the child’s asking, “Is it true?” Many fairy tales offer an answer even before the question can be asked—namely, at the very beginning of the story. For example, “Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves” starts: “In days of yore and times and tides long gone. .” The Brothers Grimm’s story “The Frog King, or Iron Henry” opens: “In olden times when wishing still helped one. .” Such beginnings make it amply clear that the stories take place on a very different level from everyday “reality.” Some fairy tales do begin quite realistically: “There once was a man and a woman who had long in vain wished for a child.” But the child who is familiar with fairy stories always extends the times of yore in his mind to mean the same as “In fantasy land . -

Snow White: Evil Witches Professor Joanna Bourke 19 November 2020

Snow White: Evil Witches Professor Joanna Bourke 19 November 2020 Each generation invents evil. And evil women have incited our imaginations since Eve first plucked that apple. One of my favourites evil women is the Evil Queen in the story of Snow White. She is the archetypical ageing woman: post-menopausal and demonised as the ugly hag, malicious crone, and depraved witch. She is evil, obscene, and threatening because of her familiarity with the black arts, her skills in mixing poisonous potions, and her possession of a magic mirror. She is also sexual and aware: like Eve, she has tasted of the Tree of Knowledge. Her story first roused the imaginations of the Brothers Grimm in 1812 and 1819: the second version stripped the story of its ribald connotations while retaining (and even augmenting) its sadism. Famously, “Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs” was set to song by Disney in 1937, a film that is often hailed as the “seminal” version. Interestingly, the word “seminal” itself comes from semen, so is encoded male. Its exploitation by Disney has helped the company generate over $48 billion dollars a year through its movies, theme parks, and memorabilia such as collectible cards, colouring-in books, “princess” gowns and tiaras, dolls, peaked hats, and mirrors. Snow White and the Evil Queen appears in literature, music, dance, theatre, fine arts, television, comics, and the internet. It remains a powerful way to castigate powerful women – as during Hillary Clinton’s bid for the White House, when she was regularly dubbed the Witch. This link between powerful women and evil witchery has made the story popular amongst feminist storytellers, keen to show how the story shapes the way children and adults think about gender and sexuality, race and class. -

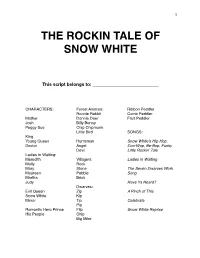

Rockin Snow White Script

!1 THE ROCKIN TALE OF SNOW WHITE This script belongs to: __________________________ CHARACTERS: Forest Animals: Ribbon Peddler Roonie Rabbit Comb Peddler Mother Donnie Deer Fruit Peddler Josh Billy Bunny Peggy Sue Chip Chipmunk Little Bird SONGS: King Young Queen Huntsman Snow White’s Hip-Hop, Doctor Angel Doo-Wop, Be-Bop, Funky Devil Little Rockin’ Tale Ladies in Waiting: Meredith Villagers: Ladies in Waiting Molly Rock Mary Stone The Seven Dwarves Work Maureen Pebble Song Martha Brick Judy Have Ya Heard? Dwarves: Evil Queen Zip A Pinch of This Snow White Kip Mirror Tip Celebrate Pip Romantic Hero Prince Flip Snow White Reprise His People Chip Big Mike !2 SONG: SNOW WHITE HIP-HOP, DOO WOP, BE-BOP, FUNKY LITTLE ROCKIN’ TALE ALL: Once upon a time in a legendary kingdom, Lived a royal princess, fairest in the land. She would meet a prince. They’d fall in love and then some. Such a noble story told for your delight. ’Tis a little rockin’ tale of pure Snow White! They start rockin’ We got a tale, a magical, marvelous, song-filled serenade. We got a tale, a fun-packed escapade. Yes, we’re gonna wail, singin’ and a-shoutin’ and a-dancin’ till my feet both fail! Yes, it’s Snow White’s hip-hop, doo-wop, be-bop, funky little rockin’ tale! GIRLS: We got a prince, a muscle-bound, handsome, buff and studly macho guy! GUYS: We got a girl, a sugar and spice and-a everything nice, little cutie pie. ALL: We got a queen, an evil-eyed, funkified, lean and mean, total wicked machine. -

Unhoming the Child: Queer Paths and Precarious Futures in Kissing the Witch

University of Hawai’i – West O’ahu DSpace Submission Nolte-Odhiambo, Carmen. "Unhoming the Child: Queer CITATION Paths and Precarious Futures In Kissing the Witch." Pacific Coast Philology 53.2 (2018): 239-50. AS PUBLISHED PUBLISHER Penn State University Press Modified from original published version to conform to ADA VERSION standards. CITABLE LINK http://hdl.handle.net/10790/5182 Article is made available in accordance with the publisher's policy and TERMS OF USE may be subject to US copyright law. Please refer to the publisher's site for terms of use. ADDITIONAL NOTES 1 Unhoming the Child: Queer Paths and Precarious Futures in Kissing the Witch Carmen Nolte-Odhiambo Abstract: Focusing on Emma Donoghue’s fairy-tale retellings for young readers, this essay explores the implications of stories that stray from the conventional script of children’s literature by rejecting normative models of belonging as well as happily-ever-after permanence. Instead of securely positioning the child on the path toward reproductive futurism and the creation of a new family home, these tales present radical visions of queer futurity and kinship and upend normative child-adult relations. Drawing in particular on Sara Ahmed’s work on happiness and Judith (Jack) Halberstam’s analysis of queer time, I analyze how Donoghue’s versions of “Cinderella” and “Hansel and Gretel” unhome their protagonists and cast them outside of heteronormative temporality. Keywords: home; children’s literature; fairy tales; queer theory; Emma Donoghue “The future is queerness’s domain,” José Esteban Muñoz writes in Cruising Utopia, because queerness, given its intimate links to hope and potentiality, “is always in the horizon” (1, 11). -

Defining and Subverting the Female Beauty Ideal in Fairy Tale Narratives and Films Through Grotesque Aesthetics

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 9-10-2015 12:00 AM Who's the Fairest of Them All? Defining and Subverting the Female Beauty Ideal in Fairy Tale Narratives and Films through Grotesque Aesthetics Leah Persaud The University of Western Ontario Supervisor Dr. Angela Borchert The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in Comparative Literature A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree in Master of Arts © Leah Persaud 2015 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Comparative Literature Commons Recommended Citation Persaud, Leah, "Who's the Fairest of Them All? Defining and Subverting the Female Beauty Ideal in Fairy Tale Narratives and Films through Grotesque Aesthetics" (2015). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 3244. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/3244 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WHO’S THE FAIREST OF THEM ALL? DEFINING AND SUBVERTING THE FEMALE BEAUTY IDEAL IN FAIRY TALE NARRATIVES AND FILMS THROUGH GROTESQUE AESTHETICS (Thesis format: Monograph) by Leah Persaud Graduate Program in Comparative Literature A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts The School of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies The University of Western Ontario London, Ontario, Canada © Leah Persaud 2015 Abstract This thesis seeks to explore the ways in which women and beauty are depicted in the fairy tales of Giambattista Basile, the Grimm Brothers, and 21st century fairy tale films. -

Gender and Fairy Tales

Issue 2013 44 Gender and Fairy Tales Edited by Prof. Dr. Beate Neumeier ISSN 1613-1878 About Editor Prof. Dr. Beate Neumeier Gender forum is an online, peer reviewed academic University of Cologne journal dedicated to the discussion of gender issues. As English Department an electronic journal, gender forum offers a free-of- Albertus-Magnus-Platz charge platform for the discussion of gender-related D-50923 Köln/Cologne topics in the fields of literary and cultural production, Germany media and the arts as well as politics, the natural sciences, medicine, the law, religion and philosophy. Tel +49-(0)221-470 2284 Inaugurated by Prof. Dr. Beate Neumeier in 2002, the Fax +49-(0)221-470 6725 quarterly issues of the journal have focused on a email: [email protected] multitude of questions from different theoretical perspectives of feminist criticism, queer theory, and masculinity studies. gender forum also includes reviews Editorial Office and occasionally interviews, fictional pieces and poetry Laura-Marie Schnitzler, MA with a gender studies angle. Sarah Youssef, MA Christian Zeitz (General Assistant, Reviews) Opinions expressed in articles published in gender forum are those of individual authors and not necessarily Tel.: +49-(0)221-470 3030/3035 endorsed by the editors of gender forum. email: [email protected] Submissions Editorial Board Target articles should conform to current MLA Style (8th Prof. Dr. Mita Banerjee, edition) and should be between 5,000 and 8,000 words in Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz (Germany) length. Please make sure to number your paragraphs Prof. Dr. Nilufer E. Bharucha, and include a bio-blurb and an abstract of roughly 300 University of Mumbai (India) words. -

Snow White in the Spanish Cultural Tradition

Bravo, Irene Raya, and María del Mar Rubio-Hernández. "Snow White in the Spanish cultural tradition: Analysis of the contemporary audiovisual adaptations of the tale." Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs: New Perspectives on Production, Reception, Legacy. Ed. Chris Pallant and Christopher Holliday. New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 2021. 249–262. Bloomsbury Collections. Web. 27 Sep. 2021. <http://dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781501351198.ch-014>. Downloaded from Bloomsbury Collections, www.bloomsburycollections.com, 27 September 2021, 23:19 UTC. Copyright © Chris Pallant and Christopher Holliday 2021. You may share this work for non- commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher, and provide a link to the Creative Commons licence. 249 14 Snow White in the Spanish cultural tradition: Analysis of the contemporary audiovisual adaptations of the tale Irene Raya Bravo and Mar í a del Mar Rubio-Hern á ndez Introduction – Snow White, an eternal and frontier-free tale As one of the most popular fairy tales, Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs has international transcendence. Not only has it been translated into numerous languages around the world, but it has also appeared in several formats since the nineteenth century. However, since 2000, an increase in both fi lm and television adaptations of fairy tales has served to retell this classic tales from a variety of different perspectives. In the numerous Snow White adaptations, formal and thematic modifi cations are often introduced, taking the story created by Disney in 1937 as an infl uential reference but altering its narrative in diverse ways. In the case of Spain, there are two contemporary versions of Snow White that participate in this trend: a fi lm adaptation called Blancanieves (Pablo Berger, 2012) and a television adaptation, included as an episode of the fantasy series Cu é ntame un cuento (Marcos Osorio Vidal, 99781501351228_pi-316.indd781501351228_pi-316.indd 224949 116-Nov-206-Nov-20 220:17:500:17:50 250 250 SNOW WHITE AND THE SEVEN DWARFS 2014). -

Blancanieves Se Despides De Los Siete Enanos: Snow White Says Goodbye to the Seven Dwarfs

Collage Volume 6 Number 1 Article 53 2012 Blancanieves se despides de los siete enanos: Snow White Says Goodbye to the Seven Dwarfs Daniel Persia Denison University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.denison.edu/collage Part of the Modern Languages Commons, Photography Commons, and the Poetry Commons Recommended Citation Persia, Daniel (2012) "Blancanieves se despides de los siete enanos: Snow White Says Goodbye to the Seven Dwarfs," Collage: Vol. 6 : No. 1 , Article 53. Available at: https://digitalcommons.denison.edu/collage/vol6/iss1/53 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Modern Languages at Denison Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Collage by an authorized editor of Denison Digital Commons. Photo by Charles O’Keefe Leopoldo María Panero (1948-) is a Spanish poet most commonly associated with the Novísimos, a reactionary, unconventional poetic group that began to question the basis of authority during Franco’s dictatorial regime. Panero’s voice is defiant yet resolute; his poetry deconstructs notions of identity by breaking traditional form. In Así se fundó Carnaby Street (1970), Panero creates a series of comic vignettes in poetic prose, distorting the reader’s memories of childhood innocence and re-mystifying a popular culture that has governed both past and present. Panero has spent much of his life in and out of psychiatric institutions, and consequently his representation of the aesthetic nightmare has evolved. Poemas del Manicomio de Mondragón (1999) reflects the shift in his poetry to a more twisted, obscure sense of futility and the nothingness that pervades human existence.