British Colour Cinematography

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Black Tent

The Black Tent (1956) and Bengazi (1955): The Image of Arabs in Two Post-Empire Journeys into the Deserts of Libya Richard Andrew Voeltz [email protected] Cameron University Volume 7.1 (2018) | ISSN 2158-8724 (online) | DOI 10.5195/cinej.2018.200 | http://cinej.pitt.edu Abstract These two little known films are both part of the cycle of post-imperial films dealing with the decline of the British Empire. They are perhaps the only films set in or near the historical period of the British Military Administration of Libya after 1945. The Black Tent frequently gets lumped in with the genre of World War II British war films. Bengazi marks the cinematic journey of the actor Victor McLaglen from The Lost Patrol (1934) to Bengazi (1955), his career encapsulating the beginning and end of the Hollywood British Empire film genre. Both films contain redemptive dramatic journeys into the deserts of Libya involving the loss of British imperial male power. The case studies of The Black Tent and Bengazi show the beginnings of new post-empire film genres and new mentalities toward the Arab “Other” that partially promotes a decolonization of western cinema. Keywords: Film, Post-Empire, Arabs, Libya New articles in this journal are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 United States License. This journal is published by the University Library System of the University of Pittsburgh as part of its D-Scribe Digital Publishing Program and is cosponsored by the University of Pittsburgh Press. The Black Tent (1956) and Bengazi (1955): The Image of Arabs in Two Post-Empire Journeys into the Deserts of Libya Richard Andrew Voeltz The Black Tent (1956, British) and Bengazi (1955, American) are perhaps the only feature films set in the last days of the British Military Administration of Libya from 1945 to 1951. -

CINERAMA: the First Really Big Show

CCINEN RRAMAM : The First Really Big Show DIVING HEAD FIRST INTO THE 1950s:: AN OVERVIEW by Nick Zegarac Above left: eager audience line ups like this one for the “Seven Wonders of the World” debut at the Cinerama Theater in New York were short lived by the end of the 1950s. All in all, only seven feature films were actually produced in 3-strip Cinerama, though scores more were advertised as being shot in the process. Above right: corrected three frame reproduction of the Cypress Water Skiers in ‘This is Cinerama’. Left: Fred Waller, Cinerama’s chief architect. Below: Lowell Thomas; “ladies and gentlemen, this is Cinerama!” Arguably, Cinerama was the most engaging widescreen presentation format put forth during the 1950s. From a visual standpoint it was the most enveloping. The cumbersome three camera set up and three projector system had been conceptualized, designed and patented by Fred Waller and his associates at Paramount as early as the 1930s. However, Hollywood was not quite ready, and certainly not eager, to “revolutionize” motion picture projection during the financially strapped depression and war years…and who could blame them? The standardized 1:33:1(almost square) aspect ratio had sufficed since the invention of 35mm celluloid film stock. Even more to the point, the studios saw little reason to invest heavily in yet another technology. The induction of sound recording in 1929 and mounting costs for producing films in the newly patented 3-strip Technicolor process had both proved expensive and crippling adjuncts to the fluidity that silent B&W nitrate filming had perfected. -

The Search for Spectators: Vistavision and Technicolor in the Searchers Ruurd Dykstra the University of Western Ontario, [email protected]

Kino: The Western Undergraduate Journal of Film Studies Volume 1 | Issue 1 Article 1 2010 The Search for Spectators: VistaVision and Technicolor in The Searchers Ruurd Dykstra The University of Western Ontario, [email protected] Abstract With the growing popularity of television in the 1950s, theaters experienced a significant drop in audience attendance. Film studios explored new ways to attract audiences back to the theater by making film a more totalizing experience through new technologies such as wide screen and Technicolor. My paper gives a brief analysis of how these new technologies were received by film critics for the theatrical release of The Searchers ( John Ford, 1956) and how Warner Brothers incorporated these new technologies into promotional material of the film. Keywords Technicolor, The Searchers Recommended Citation Dykstra, Ruurd (2010) "The Search for Spectators: VistaVision and Technicolor in The Searchers," Kino: The Western Undergraduate Journal of Film Studies: Vol. 1 : Iss. 1 , Article 1. Dykstra: The Search for Spectators The Search for Spectators: VistaVision and Technicolor in The Searchers by Ruurd Dykstra In order to compete with the rising popularity of television, major Hollywood studios lured spectators into the theatres with technical innovations that television did not have - wider screens and brighter colors. Studios spent a small fortune developing new photographic techniques in order to compete with one another; this boom in photographic research resulted in a variety of different film formats being marketed by each studio, each claiming to be superior to the other. Filmmakers and critics alike valued these new formats because they allowed for a bright, clean, crisp image to be projected on a much larger screen - it enhanced the theatre going experience and brought about a re- appreciation for film’s visual aesthetics. -

The Representation of Reality and Fantasy in the Films of Powell and Pressburger: 1939-1946

The Representation of Reality and Fantasy In the Films of Powell and Pressburger 1939-1946 Valerie Wilson University College London PhD May 2001 ProQuest Number: U642581 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest. ProQuest U642581 Published by ProQuest LLC(2015). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 The Representation of Reality and Fantasy In the Films of Powell and Pressburger: 1939-1946 This thesis will examine the films planned or made by Powell and Pressburger in this period, with these aims: to demonstrate the way the contemporary realities of wartime Britain (political, social, cultural, economic) are represented in these films, and how the realities of British history (together with information supplied by the Ministry of Information and other government ministries) form the basis of much of their propaganda. to chart the changes in the stylistic combination of realism, naturalism, expressionism and surrealism, to show that all of these films are neither purely realist nor seamless products of artifice but carefully constructed narratives which use fantasy genres (spy stories, rural myths, futuristic utopias, dreams and hallucinations) to convey their message. -

A TRIBUTE to OSWALD MORRIS OBE, DFC, AFC, BSC Introduced by Special Guests Duncan Kenworthy OBE, Chrissie Morris and Roger Deakins CBE, ASC, BSC

BAFTA HERITAGE SCREENING Monday 23 June 2O14, BAFTA, 195 Piccadilly, London W1J 9LN THE HILL: A TRIBUTE TO OSWALD MORRIS OBE, DFC, AFC, BSC Introduced by special guests Duncan Kenworthy OBE, Chrissie Morris and Roger Deakins CBE, ASC, BSC SEAN CONNERY AND HARRY ANDREW IN THE HILL THE (1965) Release yeaR: 1965 Transport Command, where as a Flight Lt. he flew Sir Anthony Runtime: 123 mins Eden to Yalta, Clement Attlee to Potsdam, and the chief of the DiRectoR: Sidney Lumet imperial general staff, Lord Alanbrooke, on a world tour. cinematogRaphy: Oswald Morris After demobilization, Ossie joined Independent Producers at With special thanks to Warner Bros and the BFI Pinewood Studios in January 1946 and was engaged as camera operator on three notable productions; Green For Danger, Launder and Gilliat’s comedy-thriller concerning a series of orn in November 1915 Oswald Morris was a murders at a wartime emergency hospital; Captain Boycott, a 1947 dedicated film fan in his teenage years, working as historical drama, again produced by Launder and Gilliat and a cinema projectionist in his school holidays, before Oliver Twist, David Lean’s stunning adaptation of the classic novel entering the industry in 1932 as a runner and clapper by Charles Dickens photographed by Guy Green. Bboy at Wembley Studios, a month short of his 17th birthday. In 1949, Ossie gained his first screen credit as Director of The studio churned out quota quickies making a movie a week Photography on Golden Salamander, starring Trevor Howard as at a cost of one pound per foot of film. -

NFTS 2014 Financial Statements Web2.Pdf

Contents Statement of the Board of Governors .................................................................................................................. 2 Operating and Financial Review ....................................................................................................................... 5 Introduction ..................................................................................................................................................... 5 1 Statement of Public Benefit ............................................................................................................................. 5 1.1 Object, Vision and Values .......................................................................................................................... 6 1.2 Outreach and Widening Participation ...................................................................................................... 6 1.3 Community Engagement .......................................................................................................................... 6 1. 4 Fundraising .............................................................................................................................................. 7 2 Strategy and Risk Analysis ............................................................................................................................. 7 2.1 Strategic Plan .......................................................................................................................................... -

Modus Operandi Films and High Point Media Group Present

Modus Operandi Films and High Point Media Group Present A film by Craig McCall Worldwide Sales: High Point Media Group Contact in Cannes: Residences du Grand Hotel, Cormoran II, 3 rd Floor: Tel: +33 (0) 4 93 38 05 87 London Contact: Tel: +44 20 7424 6870. Fax +44 20 7435 3281 [email protected] CAMERAMAN: The Life & Work of Jack Cardiff page 1 of 27 © Modus Operandi Films 2010 HP PRESS KIT CAMERAMAN: The Life and Work of Jack Cardiff www.jackcardiff.com Contents: - Film Synopsis p 3 - 10 Facts About Jack p 4 - Jack Cardiff Filmography p 5 - Quotes about Jack p 6 - Director’s Notes p 7 - Interviewee’s p 8 - Bio’s of Key Crew p10 - Director's Q&A p14 - Credits p 19 CAMERAMAN: The Life & Work of Jack Cardiff page 2 of 27 © Modus Operandi Films 2010 HP PRESS KIT CAMERAMAN : The Life and Work of Jack Cardiff A Documentary Feature Film Logline: Celebrating the remarkable nine decade career of legendary cinematographer, Jack Cardiff, who provided the canvas for classics like The Red Shoes and The African Queen . Short Synopsis: Jack Cardiff’s career spanned an incredible nine of moving picture’s first ten decades and his work behind the camera altered the look of films forever through his use of Technicolor photography. Craig McCall’s passionate film about the legendary cinematographer reveals a unique figure in British and international cinema. Long Synopsis: Cameraman illuminates a unique figure in British and international cinema, Jack Cardiff, a man whose life and career are inextricably interwoven with the history of cinema spanning nine decades of moving pictures' ten. -

Introduction

CINEMATOGRAPHY Mailing List the first 5 years Introduction This book consists of edited conversations between DP’s, Gaffer’s, their crew and equipment suppliers. As such it doesn’t have the same structure as a “normal” film reference book. Our aim is to promote the free exchange of ideas among fellow professionals, the cinematographer, their camera crew, manufacturer's, rental houses and related businesses. Kodak, Arri, Aaton, Panavision, Otto Nemenz, Clairmont, Optex, VFG, Schneider, Tiffen, Fuji, Panasonic, Thomson, K5600, BandPro, Lighttools, Cooke, Plus8, SLF, Atlab and Fujinon are among the companies represented. As we have grown, we have added lists for HD, AC's, Lighting, Post etc. expanding on the original professional cinematography list started in 1996. We started with one list and 70 members in 1996, we now have, In addition to the original list aimed soley at professional cameramen, lists for assistant cameramen, docco’s, indies, video and basic cinematography. These have memberships varying from around 1,200 to over 2,500 each. These pages cover the period November 1996 to November 2001. Join us and help expand the shared knowledge:- www.cinematography.net CML – The first 5 Years…………………………. Page 1 CINEMATOGRAPHY Mailing List the first 5 years Page 2 CINEMATOGRAPHY Mailing List the first 5 years Introduction................................................................ 1 Shooting at 25FPS in a 60Hz Environment.............. 7 Shooting at 30 FPS................................................... 17 3D Moving Stills...................................................... -

My Billionaire Mom Chapter 701 - 800 Translation by U/ Dspacedude

Read full book at: https://www.webcilo.com/boards/topic/9 My Billionaire Mom Chapter 701 - 800 Translation by u/ dspacedude My mother is taking you out of Chapter 701 of the Baller's audio novel! Listen online with novels "Of course I am alive! Fear of me dying? Do you care so much about me? I haven't seen it before!" Chuck was injured, and this was hit with several bodyguards! Just after the black rose entered the private room, there were several bodyguards surrounding Chuck! Chuck instantly knew what was happening and knew that Black Rose was definitely dangerous. He didn't panic and ran out with the utmost effort! Why run? Very simple, several bodyguards joined forces, Chuck had self-knowledge, it is unlikely to be able to play, black roses are also dangerous, so delaying it will definitely not work! So run, lead these people out, and then run back yourself, take the black rose away, this is the best way! However, the few people who were led out were so powerful that Chuck was still injured, kicked in the back, and vomited blood. But for the safety of Black Rose, he resisted it and had to rush back! "No, I didn't care about you. You are dead. I can't explain to your mother Karen li!" Black Rose shook her head, and she felt pain in her body. 1 Read full book at: https://www.webcilo.com/boards/topic/9 Chuck is still alive, she will not be so desperate, the crazy aftermath just came out. -

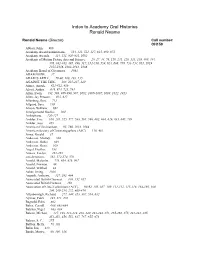

Index to Academy Oral Histories Ronald Neame

Index to Academy Oral Histories Ronald Neame Ronald Neame (Director) Call number: OH159 Abbott, John, 906 Academy Award nominations, 314, 321, 511, 517, 935, 969, 971 Academy Awards, 314, 511, 950-951, 1002 Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Science, 20, 27, 44, 76, 110, 241, 328, 333, 339, 400, 444, 476, 482-483, 495, 498, 517, 552-556, 559, 624, 686, 709, 733-734, 951, 1019, 1055-1056, 1083-1084, 1086 Academy Board of Governors, 1083 ADAM BEDE, 37 ADAM’S APPLE, 79-80, 100, 103, 135 AGAINST THE TIDE, 184, 225-227, 229 Aimee, Anouk, 611-612, 959 Alcott, Arthur, 648, 674, 725, 784 Allen, Irwin, 391, 508, 986-990, 997, 1002, 1006-1007, 1009, 1012, 1013 Allen, Jay Presson, 925, 927 Allenberg, Bert, 713 Allgood, Sara, 239 Alwyn, William, 692 Amalgamated Studios, 209 Ambiphone, 126-127 Ambler, Eric, 166, 201, 525, 577, 588, 595, 598, 602, 604, 626, 635, 645, 709 Ambler, Joss, 265 American Film Institute, 95, 766, 1019, 1084 American Society of Cinematogaphers (ASC), 118, 481 Ames, Gerald, 37 Anderson, Mickey, 366 Anderson, Robin, 893 Anderson, Rona, 929 Angel, Heather, 193 Ankers, Evelyn, 261-263 anti-Semitism, 562, 572-574, 576 Arnold, Malcolm, 773, 864, 876, 907 Arnold, Norman, 88 Arnold, Wilfred, 88 Asher, Irving, 1026 Asquith, Anthony, 127, 292, 404 Associated British Cinemas, 108, 152, 857 Associated British Pictures, 150 Association of Cine-Technicians (ACT), 90-92, 105, 107, 109, 111-112, 115-118, 164-166, 180, 200, 209-210, 272, 469-470 Attenborough, Richard, 277, 340, 353, 387, 554, 632 Aylmer, Felix, 185, 271, 278 Bagnold, Edin, 862 Baker, Carroll, 680, 883-884 Balchin, Nigel, 683, 684 Balcon, Michael, 127, 198, 212-214, 238, 240, 243-244, 251, 265-266, 275, 281-282, 285, 451-453, 456, 552, 637, 767, 855, 878 Balcon, S. -

British Society of Cinematographers

Best Cinematography in a Theatrical Feature Film 2020 Erik Messerschmidt ASC Mank (2020) Sean Bobbitt BSC Judas and the Black Messiah (2021) Joshua James Richards Nomadland (2020) Alwin Kuchler BSC The Mauritanian (2021) Dariusz Wolski ASC News of the World (2020) 2019 Roger Deakins CBE ASC BSC 1917 (2019) Rodrigo Prieto ASC AMC The Irishman (2019) Lawrence Sher ASC Joker (2019) Jarin Blaschke The Lighthouse (2019) Robert Richardson ASC Once Upon a Time … in Hollywood (2019) 2018 Alfonso Cuarón Roma (2018) Linus Sandgren ASC FSF First Man (2018) Lukasz Zal PSC Cold War(2018) Robbie Ryan BSC ISC The Favourite (2018) Seamus McGarvey ASC BSC Bad Times at the El Royale (2018) 2017 Roger Deakins CBE ASC BSC Blade Runner 2049 (2017) Ben Davis BSC Three Billboards outside of Ebbing, Missouri (2017) Bruno Delbonnel ASC AFC Darkest Hour (2017) Dan Laustsen DFF The Shape of Water (2017) 2016 Seamus McGarvey ASC BSC Nocturnal Animals (2016) Bradford Young ASC Arrival (2016) Linus Sandgren FSF La La Land (2016) Greig Frasier ASC ACS Lion (2016) James Laxton Moonlight (2016) 2015 Ed Lachman ASC Carol (2015) Roger Deakins CBE ASC BSC Sicario (2015) Emmanuel Lubezki ASC AMC The Revenant (2015) Janusz Kaminski Bridge of Spies (2015) John Seale ASC ACS Mad Max : Fury Road (2015) 2014 Dick Pope BSC Mr. Turner (2014) Rob Hardy BSC Ex Machina (2014) Emmanuel Lubezki AMC ASC Birdman or (The Unexpected Virtue of Ignorance) (2014) Robert Yeoman ASC The Grand Budapest Hotel (2014) Lukasz Zal PSC & Ida (2013) Ryszard Lenczewski PSC 2013 Phedon Papamichael ASC -

Mise En Page 1

octobre 2013 La lettre n° 235 R D - e g n a h c u D e h p o t s i r h C r a p é i h p a r g o t o h p , r i o s e c s t r o m t n o s s o r é h s o N , t l u a r r e P d i v a D e d m l i f les entretiens de l'AFC : u d e g a n r AFC u THIERRY ARBOGAST o t e l r pour Malavita u s e de Luc Besson > p. 16 n è t s g n CHRISTOPHE DUCHANGE u t u a pour Nos héros sont morts ce soir s e l u de David Perrault > p. 18 o p m a AFC ' d JEANNE LAPOIRIE n o i t pour Un château en Italie a l l a t de Valeria Bruni Tedeschi > p. 20 s n I e s i e a e u i FILMS AFC SUR LES ÉCRANS > p. 2 ACTIVITÉS AFC > p. 4 ç q h i n p h a r a s p r F r a g r u IN MEMORIAM > p. 4 FESTIVALS > p. 8 ÇÀ ET LÀ > p. 9 n o e g t o t i o o c t t e h a a i r i p c m LA CST > p. 22 NOS ASSOCIÉS > p. 23 PRESSE > p. 26 d o a é l s s n s i e e C d d A LECTURE > p.