Modernising Hong Kong's Water Management Policy PART II

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annex C Information on Re-Tendering Exercises on the Relevant Service Contracts Conducted/To Be Conducted by FEHD, LCSD and HD in 2018 and 2019

- 1 - Annex C Information on re-tendering exercises on the relevant service contracts conducted/to be conducted by FEHD, LCSD and HD in 2018 and 2019 Procuring department: FEHD Start date of Name of existing/previous new service Service districts involved Name of new contractor contractor contract 1. 1.1.2018 Depots of Transport Section Law's Cleaning Services Limited Integrity Service Limited 2. 1.1.2018 Po On Road Municipal Services Building in Sham Shui Po Johnson Cleaning Services Company Baguio Cleaning Services Company District and Hung Hom Municipal Services Building in Limited Limited Kowloon City District 3. 1.1.2018 Markets in Kwun Tong District Johnson Cleaning Services Company World Environmental Services Limited Limited 4. 1.1.2018 Markets in Tsuen Wan District Johnson Cleaning Services Company Johnson Cleaning Services Company Limited Limited 5. 1.1.2018 Markets in Tuen Mun District Lapco Service Limited Baguio Pest Management Limited 6. 1.1.2018 Public place in Wan Chai District (East) Lapco Service Limited Johnson Cleaning Services Company Limited 7. 1.1.2018 Public place in Wan Chai District (East) Lapco Service Limited Lapco Service Limited 8. 1.2.2018 Markets in Sha Tin District Johnson Cleaning Services Company Lapco Service Limited Limited 9. 1.2.2018 Markets in Islands District Johnson Cleaning Services Company Lapco Service Limited Limited 10. 1.3.2018 Public place in the Territory ISS Environmental Services (HK) ISS Environmental Services (HK) - 2 - Start date of Name of existing/previous new service Service districts involved Name of new contractor contractor contract Limited Limited 11. 1.3.2018 Public place in Wan Chai District (East) Lapco Service Limited Baguio Cleaning Services Company Limited 12. -

RNTPC Paper No. A/NE-TK/681 for Consideration by the Rural and New Town Planning Committee on 29.5.2020

RNTPC Paper No. A/NE-TK/681 For Consideration by the Rural and New Town Planning Committee on 29.5.2020 APPLICATION FOR PERMISSION UNDER SECTION 16 OF THE TOWN PLANNING ORDINANCE APPLICATION NO. A/NE-TK/681 Applicants Messrs. WONG Wong Po Stanley and WONG Pak Sing represented by Ms. YU Tsz Shan Site Government land in D.D. 28, Tai Mei Tuk, Tai Po, N.T. Site Area About 340m² Land Status Government land Plan Approved Ting Kok Outline Zoning Plan (OZP) No. S/NE-TK/19 Zoning “Conservation Area” (“CA”) Application Temporary Shop and Services (Selling of Refreshment, Hiring of Fishing related Accessories and Storage) for a Period of Three Years 1. The Proposal 1.1 The applicants seek planning permission to use the application site (the Site) for temporary shop and services (selling of refreshment, hiring of fishing related accessories and storage) for a period of three years. The Site falls within an area zoned “CA” on the approved Ting Kok OZP No. S/NE-TK/19. According to the Notes of the OZP, temporary use not exceeding a period of three years requires planning permission from the Town Planning Board (the Board), notwithstanding that the use is not provided for in terms of the OZP. 1.2 The applied use comprises two single-storey structures (2.44m high) converted from containers, with a total floor area of about 45m2 (Drawings A-1 and A- 2). The operation hours are from 7:00 am to 10:00 pm daily. The Site is accessible from Tai Mei Tuk Road. -

29 July 2020 Notice on BOCHK Branch Services Bank of China

29 July 2020 Notice on BOCHK Branch Services Bank of China (Hong Kong) Limited (“BOCHK”) would like to notify its customers and the general public that in view of the current novel coronavirus outbreak, we will review current measures from time to time, and adjust branch services as appropriate. Except for certain branches listed below, 180 BOCHK branches across the city will continue to provide services. Customers may also access banking services via our 24-hour Self-service Banking Centres, ATMs, or electronic means such as Mobile Banking, Internet Banking and Phone Banking. Details of BOCHK outlets are available at our website (www.bochk.com/en/branch.html). For enquiries, please call BOCHK Customer Service Hotline at (852) 3988 2388. From 29 July 2020 (Wednesday) onwards, the services of the following branch will be suspended until further notice: Branch Name Branch Address Hong Kong Shop 4, G/F, Causeway Centre, 28 Harbour Road, Wan Harbour Road Branch# Chai The services of the following branches will remain suspended until further notice: Branch Name Branch Address Kowloon Yuk Wah Street Branch 46-48 Yuk Wah Street, Tsz Wan Shan Shop Nos. A317 and A318, 3/F, Choi Wan Shopping Choi Wan Estate Branch# Centre Phase II, 45 Clear Water Bay Road, Ngau Chi Wan Choi Hung Branch 19 Clear Water Bay Road, Ngau Chi Wan Diamond Hill Branch# G107 Plaza Hollywood, Diamond Hill Ma Tau Kok Road Branch# 39-45 Ma Tau Kok Road, To Kwa Wan Shop 206A, Dragon Centre, 37K Yen Chow Street, Dragon Centre Branch Sham Shui Po Shop 108, Lei Cheng Uk Commercial -

260193224.Pdf

4 14 Tai Tam Upper Reservoir Tai Tam Tuk Reservoir Dam 1912-1917 Valve House 1883 - 1888 12 10 12 6 Tai Tam Byewash Reservoir The masonry-faced concrete gravity dam features ornamental parapets and The valve house forthe dam is located atone third of the way 12 large spillways to handle water overflow. Spillways ateither end ofthe along the top ofthe dam. A simple square structure with a Valve House 1904 damare the original spillways while the other10 have been modified with single doorand small window openings which have since been additionalconcre te structures to actas siphon spillways. Over the spillways blocked, the valve house has been builtin rock-faced rusticated are a road deck formed by 12 arches supported by half-round granite granite blocks. The original hipped roofhas been replaced with columns where busy road runs along connecting Stanley and TaiTam with a flatroof with the projecting cornice, supported by carved ChaiWan and Shek O. ornamental corbels, remains intact. Asmall valve house, located halfway along the 15 16 5 subsidiary dam,is rectangular in shape and features rock-faced granite walls,a flatroofand Tai Tam Tuk Reservoir Valve House 1917 Tai Tam Tuk Reservoir windows. Access walkways along the dam Tai Tam Upper Reservoir R ecorder House 1917 and Memorial Stone 1918 allowed regularins pections and are used today Tunnel Inlet 1883 - 1888 by hikers following trails in TaiTam Country 1918 Park. Original castiron safety railings remain (SirHenryMay, 1912-1918) in place. The valve house is situated near the south end ofthe Tai TamTuk Reservoir dam. The valve house was builton a projecting platformwhich Acommemorative stone is ere cted near the southern end at the top ofthe damto mark the completion ofthe Tai TamReservoirScheme has cantilevered steelbalconies or catwalks fixed to the frontof it. -

Page 1 of 12 De-Stratification of Plover Cove Reservoir by Aeration Project Profile

De-stratification of Plover Cove Reservoir by Aeration Project Profile 1. Basic Information 1.1 Project Title De-stratification of Plover Cove Reservoir by Aeration. 1.2 Purpose and Nature of Project 1.2.1 Apart from the surface run-off collected in its direct and indirect gathering grounds, the majority of the storage in the Plover Cove (PC) Reservoir comes from Dongjiang, the water quality of which has been deteriorating since early 1990s. The high concentration of nutrients in the form of nitrate and phosphate stimulates algae growth in the impounded water, particularly in favorable conditions of hot, calm, clear weather in summer months. 1.2.2 The excessive algal growth results in high pH values, odour and taste problems that adversely affect the operation of water treatment works receiving raw water from the reservoir. For example, the pH values in the PC water had risen up to 10 and above in June 2003. This had to a great extent upset the clarification process in the following water treatment works (WTW) for which PC water is the main source of supply:- - Ma On Shan WTW - Pak Kong WTW Other than this, algae blooms have also resulted in odour and unsightliness in the reservoir water. 1.2.3 The results of regular monitoring reveal that thermal stratification often occurs in Plover Cove Reservoir and divides the reservoir water into three layers, namely upper warm layer, thermocline intermediate layer and cool bottom layer. The intermediate layer serves as a barrier in between the upper and bottom layers and isolates the bottom layer from the air at the surface. -

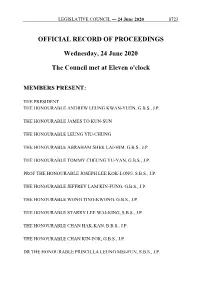

Official Record of Proceedings

LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL ― 24 June 2020 8723 OFFICIAL RECORD OF PROCEEDINGS Wednesday, 24 June 2020 The Council met at Eleven o'clock MEMBERS PRESENT: THE PRESIDENT THE HONOURABLE ANDREW LEUNG KWAN-YUEN, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE JAMES TO KUN-SUN THE HONOURABLE LEUNG YIU-CHUNG THE HONOURABLE ABRAHAM SHEK LAI-HIM, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE TOMMY CHEUNG YU-YAN, G.B.S., J.P. PROF THE HONOURABLE JOSEPH LEE KOK-LONG, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE JEFFREY LAM KIN-FUNG, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE WONG TING-KWONG, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE STARRY LEE WAI-KING, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE CHAN HAK-KAN, B.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE CHAN KIN-POR, G.B.S., J.P. DR THE HONOURABLE PRISCILLA LEUNG MEI-FUN, S.B.S., J.P. 8724 LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL ― 24 June 2020 THE HONOURABLE WONG KWOK-KIN, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE MRS REGINA IP LAU SUK-YEE, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE PAUL TSE WAI-CHUN, J.P. THE HONOURABLE CLAUDIA MO THE HONOURABLE MICHAEL TIEN PUK-SUN, B.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE STEVEN HO CHUN-YIN, B.B.S. THE HONOURABLE FRANKIE YICK CHI-MING, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE WU CHI-WAI, M.H. THE HONOURABLE YIU SI-WING, B.B.S. THE HONOURABLE MA FUNG-KWOK, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE CHARLES PETER MOK, J.P. THE HONOURABLE CHAN CHI-CHUEN THE HONOURABLE CHAN HAN-PAN, B.B.S., J.P. -

Capital Works Reserve Fund

Secondary (Continued) Capital Works Reserve Fund STATEMENT OF PROJECT PAYMENTS FOR 2009-10 Head 709 — WATERWORKS Subhead Approved Original Project Estimate Estimate Cumulative Expenditure Amended to 31.3.2010 Estimate Actual $’000 $’000 $’000 Infrastructure Water Supplies — Combined fresh/salt water supplies 9069WC Improvement of water supply to Western, Central 263,800 243 and Wan Chai areas and extension of water supply 263,438 243 - to Central and Wan Chai reclamation — stage 1 9076WC Improvement to Hong Kong Central mid-level and 229,300 58,800 high level areas water supply — remaining works 188,414 92,576 86,719 9085WC Water supply to South East Kowloon development, 615,700 - stage 1 — works 495,437 250 29 9090WC Replacement and rehabilitation of water mains, 2,063,400 108,000 stage 1 phase 1 1,931,777 179,000 157,211 9091WC Water supply to new developments in Yau Tong 377,600 6,294 area 204,725 7,800 7,706 9092WC Water supply to West Kowloon Reclamation, 162,190 5,000 stage 2 — main works 82,803 5,000 3,373 9174WC Replacement and rehabilitation of water mains, 1,267,100 266,000 stage 1 phase 2 1,022,750 320,000 317,691 9175WC Replacement and rehabilitation of water mains, 115,300 750 stage 1 phase 1 (part 1) works in Sheung Shui, Tai 74,596 4,204 4,199 Po, Sha Tin and Mong Kok 9177WC Replacement and rehabilitation of water mains, 69,800 280 stage 1 phase 1B — detailed design and advance 69,332 280 - works 9179WC Replacement and rehabilitation of water mains, 117,500 1,180 stage 1 phase 1 (part 2) — works in Yuen Long, 99,358 4,160 -

Annex Compulsory Testing Notices Issued by the Secretary for Food

Annex Compulsory Testing Notices issued by the Secretary for Food and Health on December 30, 2020 Amended List of Specified Premises 1. Hibiscus House, Ma Tau Wai Estate, 9 Shing Tak Street, Kowloon City, Kowloon, Hong Kong 2. David Mansion, 93-103 Woosung Street, Yau Ma Tei, Kowloon, Hong Kong 3. Tung Hoi House, Tai Hang Tung Estate, 88 Tai Hang Tung Road, Shek Kip Mei, Kowloon, Hong Kong 4. Un Mun House, Un Chau Estate, 303 Un Chau Street, Sham Shui Po, Kowloon, Hong Kong 5. Fu Wen House, Fu Cheong Estate, 19 Sai Chuen Road, Sham Shui Po, Kowloon, Hong Kong 6. Cherry House, So Uk Estate, 380 Po On Road, Sham Shui Po, Kowloon, Hong Kong 7. Tao Tak House, Lei Cheng Uk Estate, 10 Fat Tseung Street, Sham Shui Po, Kowloon, Hong Kong 8. Scenic Court, 451-461 Shun Ning Road, Sham Shui Po, Kowloon, Hong Kong 9. Block 11, Rhythm Garden, 242 Choi Hung Road, Wong Tai Sin, Kowloon, Hong Kong 10. Chi Siu House, Choi Wan (I) Estate, 45 Clear Water Bay Road, Wong Tai Sin, Kowloon, Hong Kong 11. Sau Man House, Choi Wan (I) Estate, 45 Clear Water Bay Road, Wong Tai Sin, Kowloon, Hong Kong 12. Kai Fai House, Choi Wan (II) Estate, 55 Clear Water Bay Road, Wong Tai Sin, Kowloon, Hong Kong 13. Ching Yuk House, Tsz Ching Estate, 80 Tsz Wan Shan Road, Wong Tai Sin, Kowloon, Hong Kong 14. Ching Tai House, Tsz Ching Estate, 80 Tsz Wan Shan Road, Wong Tai Sin, Kowloon, Hong Kong 15. -

Open Space at Hing Wah Street West, Sham Shui Po

For discussion PWSC(2015-16)38 (Date to be confirmed) ITEM FOR PUBLIC WORKS SUBCOMMITTEE OF FINANCE COMMITTEE HEAD 703 – BUILDINGS Recreation, Culture and Amenities – Open spaces 434RO – Open space at Hing Wah Street West, Sham Shui Po Members are invited to recommend to the Finance Committee the upgrading of 434RO to Category A at an estimated cost of $122 million in money-of-the-day prices. PROBLEM There are insufficient sports and recreation facilities in the vicinity of Hing Wah Street West, Sham Shui Po to meet the needs of the local community. PROPOSAL 2. The Director of Architectural Services, with the support of the Secretary for Home Affairs, proposes to upgrade 434RO to Category A at an estimated cost of $122 million in money-of-the-day (MOD) prices for the development of open space at Hing Wah Street West, Sham Shui Po. / PROJECT ….. PWSC(2015-16)38 Page 2 PROJECT SCOPE AND NATURE 3. The project site occupies an area of around 8 392 square metres (m2) at the junction of Hing Wah Street West and Tung Chau Street in Sham Shui Po. The proposed scope of works under the project comprises- (a) a garden with soft landscaping and seating areas; (b) an area with fitness stations for the elderly; (c) a children’s play area with a designated area for tri-cycling; (d) a pet garden; (e) a 7-a-side artificial turf football pitch; and (f) a service block with ancillary facilities including toilets, changing rooms, a babycare room, a management office and a store room. -

For Discussion on Task Force on Land Supply 5 December 2017 Paper No

For discussion on Task Force on Land Supply 5 December 2017 Paper No. 12/2017 TASK FORCE ON LAND SUPPLY Reclaiming the Reservoirs PURPOSE Some members of the public suggested releasing and reclaiming reservoirs for large-scale housing development. This paper provides Members with the background information about the water supply in Hong Kong, and the potential challenges in taking forward this suggestion (“the suggestion”). BACKGROUND Water Supply in Hong Kong 2. Hong Kong does not have large rivers or lakes. Its annual rainfall averages around 2 400 mm and takes place mainly in the summer months. Coupled with Hong Kong’s hilly terrain, collection of rain water for potable uses has always been a challenge in the water supply history of Hong Kong. Catchwaters and reservoirs are constructed to deal with the uneven distribution of rainfall. With the continuous urbanization and economic development, the Government has been adopting a multi-barrier approach to control the risk of pollution of our valuable water resources. This includes designating about 30% of the territories as water gathering grounds within which developments are under strict control and adopting advanced water treatment technology before distributing the treated water for consumption by the citizen. 3. Since the first reservoir system was built in 1863, Hong Kong now has a total of 17 reservoirs1 (Figure 1) which altogether have a storage capacity of 586 million cubic metres (MCM) collecting on average an annual yield of around 246 MCM. Among these reservoirs, the High Island Reservoir (HIR) and the Plover Cove Reservoir (PCR) with storage capacity of 281 MCM and 230 MCM respectively are the two largest reservoirs, accounting for 87% of the total storage capacity. -

Hong Kong Housing Authority Redevelopment of So Uk Estate Air Ventilation Assessment – Initial Study Report

Hong Kong Housing Authority Redevelopment of So Uk Estate Air Ventilation Assessment – Initial Study Report Issue 1 | 17 Feb 2015 This report takes into account the particular instructions and requirements of our client. It is not intended for and should not be relied upon by any third party and no responsibility is undertaken to any third party. Job number 25236-03 Ove Arup & Partners Hong Kong Ltd Level 5 Festival Walk 80 Tat Chee Avenue Kowloon Tong Kowloon Hong Kong www.arup.com Hong Kong Housing Authority Redevelopment of So Uk Estate Air Ventilation Assessment – Initial Study Report Contents Page Executive Summary 1 1. Introduction 4 1.1 Project Background 4 1.2 Objective 4 1.3 Study Tasks 4 2. Background Information 5 2.1 Site Characteristics 5 2.2 Study Scenarios 6 3. Methodology of AVA Study 13 3.1 Wind Availability 13 3.2 Study Area 16 3.3 Test Point for Local and Site Ventilation Assessment 18 3.4 Assessment Tools 19 4. Results and Discussion 22 4.1 Overall Pattern of Ventilation Performance 22 4.2 Directional Analysis 24 4.3 SVR and LVR 40 4.4 Focus Areas 41 5. Wind Enhancement Features 43 5.1 Stepping Profile of Building Height 43 5.2 Local Air Paths 45 5.3 Empty Bays 48 6. Conclusion 51 Appendices Appendix A VR Result Tables Appendix B Directional VR Contour Plots Appendix C Directional VR Vector Plot | Issue 1 | 17 Feb 2015 \\HKGAET092\PROJECT\JAVIER\SOUKESTATE\AVA_PROPOSED_JUL14\REPORT\AVA_STUDY_SOUKV07_ISSUE1.DOCX Hong Kong Housing Authority Redevelopment of So Uk Estate Air Ventilation Assessment – Initial Study Report Executive Summary Ove Arup and Partners Hong Kong Limited (Arup) is commissioned by Hong Kong Housing Authority (HKHA) to conduct Air Ventilation Assessment (AVA) study for the Redevelopment of So Uk Estate Phases 1 and 2 (the Development). -

FIELDWORK Briefing

Fieldwork Exercise Briefing Basic needs 衣 Clothing → Shopping / retail 食 Food 住 Housing Hong Kong 行 Transportation → Communication A vibrant city for our smart future EdUHK New Territories Kowloon Lantau Is. Hong Kong Is. Population – 7.4M HKI: 17.5% KLN: 30.3% NT: 52.2% Density – 6690 / km2 Hong Kong’s Residential Area Density Source: LSE Cities Per capita living space in selected Asian cities (LegCo Research Office 2016) 400 363 350 339 323 300 250 216 / cap 2 195 ft 200 161 150 100 50 0 Taipei (2014) Tokyo (2013) Singapore (2014) Macau (2015) Shanghai (2015) Hong Kong (2015) Land Utilization in Hong Kong 2018 [km2] (Planning Dept. 2019) 6, 1% 31, 3% 5, 0% Recidential 78, 7% 27, 2% Commercial 53, 5% Industrial 67, 6% Institutional/Open Space Transportation 45, 4% Other Urban 66, 6% Agriculture Non-built-up Woodland/Shrubland/Grassland/ Sub-total: 770 km2 733, 66% Wetland Barren Land 75.2% Water Bodies Country Parks (AFCD 2017) Total Area 434 km2 39.1% Water Gathering Grounds Plover Cove Reservoir Tai Lam Chung Reservoir Great Outdoors Beaches Global Geopark Hikes E.g. Tai Long Sai Wan Beach E.g. Dragon’s Back & Kowloon Peak Cycling Mai Po Nature Reserve Hong Kong Wetland Park E.g. Nam Sang Wai, Shatin to Tai Mei Tuk or Wu Kai Sha Rail System Time headway 1 = 푓푟푒푞푢푒푛푐푦 Transit-oriented development Development Model (Source: Sylvie Nguyen/HKU) District road 6-min Public walking Public open distance open Space 500 meters District center Space Rail spine Rail station Low- High density private housing Low- density density land High density