Red Meat and Health Getting to the Heart of the Matter

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

To Eat Or Not to Eat Red Meat. a Closer Look at the Relationship Between Restrained Eating and Vegetarianism in College Females

W&M ScholarWorks Psychological Sciences Articles & Book Chapters Psychological Sciences Fall 11-2-2011 To eat or not to eat red meat. A closer look at the relationship between restrained eating and vegetarianism in college females Catherine A. Forestell College of William and Mary, [email protected] Andrea M. Spaeth College of William and Mary Stephanie A. Kane College of William and Mary Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/psychologypub Part of the Psychology Commons Recommended Citation Forestell, Catherine A.; Spaeth, Andrea M.; and Kane, Stephanie A., To eat or not to eat red meat. A closer look at the relationship between restrained eating and vegetarianism in college females (2011). Appetite, 58(1), 319-325. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2011.10.015 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Psychological Sciences at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Psychological Sciences Articles & Book Chapters by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Our reference: APPET 1355 P-authorquery-v10 AUTHOR QUERY FORM Journal: APPET Please e-mail or fax your responses and any corrections to: E-mail: [email protected] Article Number: 1355 Fax: +31 2048 52799 Dear Author, Please check your proof carefully and mark all corrections at the appropriate place in the proof (e.g., by using on-screen annotation in the PDF file) or compile them in a separate list. Note: if you opt to annotate the file with software other than Adobe Reader then please also highlight the appropriate place in the PDF file. -

REDUCTION of PURINE CONTENT in COMMONLY CONSUMED MEAT PRODUCTS THROUGH RINSING and COOKING by Anna Ellington (Under the Directio

REDUCTION OF PURINE CONTENT IN COMMONLY CONSUMED MEAT PRODUCTS THROUGH RINSING AND COOKING by Anna Ellington (Under the direction of Yen-Con Hung) Abstract The commonly consumed meat products ground beef, ground turkey, and bacon were analyzed for purine content before and after a rinsing treatment. The rinsing treatment involved rinsing the meat samples using a wrist shaker in 5:1 ratio water: sample for 2 or 5 minutes then draining or centrifuging to remove water. The total purine content of 25% fat ground beef significantly decreased (p<0.05) from 8.58 mg/g protein to a range of 5.17-7.26 mg/g protein after rinsing treatments. After rinsing and cooking an even greater decrease was seen ranging from 4.59-6.32 mg/g protein. The total purine content of 7% fat ground beef significantly decreased from 7.80 mg/g protein to a range of 5.07-5.59 mg/g protein after rinsing treatments. A greater reduction was seen after rinsing and cooking in the range of 4.38-5.52 mg/g protein. Ground turkey samples showed no significant changes after rinsing, but significant decreases were seen after rinsing and cooking. Bacon samples showed significant decreases from 6.06 mg/g protein to 4.72 and 4.49 after 2 and 5 minute rinsing and to 4.53 and 4.68 mg/g protein after 2 and 5 minute rinsing and cooking. Overall, this study showed that rinsing foods in water effectively reduces total purine content and subsequent cooking after rinsing results in an even greater reduction of total purine content. -

Using of Horsemeat As an Additional Source of Raw Materials for Expanding the Range of Meat Products

38 Specialized and multidisciplinary scientific researches Volume 2 . DOI 10.36074/11.12.2020.v2.10 USING OF HORSEMEAT AS AN ADDITIONAL SOURCE OF RAW MATERIALS FOR EXPANDING THE RANGE OF MEAT PRODUCTS ORCID ID: 0000-0002-6591-0414 Ihor Strashynskyi Ph.D, Associate Professor, Associate Professor Departmentof Meat and Meat Products Technology National University of Food Technologies ORCID ID: 0000-0002-8816-0388 Oksana Fursik Assistant Departmentof Meat and Meat ProductsTechnology Educational and Scientific Institute of Food Technologies National University of Food Technologies UKRAINE Today, due to the extensive development of intensive industrial growing of farm animals, such as poultry, pigs and, to a lesser extent, cattle, the production of horse meat almost all over the world, with the exception countries and regions with traditionally developed herd horse breeding, is inferior to the production of these animals meat and it is mainly used in the manufacture certain varieties of sausages to improve the structural and mechanical properties of finished products, as well as their piquant taste. There are regions in the world where horse meat is widely used as the main meat food product. Horse meat is now available in France, Belgium and Sweden, where horse meat sales outnumber mutton meat sales. In France, horse meat consumption is 0.4% of all meat consumed. There are about 750 horse meat butchers in the country and about 11,000 farmers who raise horses for sale for meat. The main part of horse meat products that produced in France are exported to Italy. Italians consume twice as much horse meat as the French and love the meat of young horses, while the French prefer red meat from older horses [1]. -

Don't Fall for Tricky Meat & Poultry Claims

Lean? here do Wthe bro- chures, posters, and voluntary labels for meat get their num- bers? In most Don’t fall for tricky meat cases, from the USDA’s data- & poultry claims base. And where does the USDA BY LINDSAY MOYER & JENNIFER URBAN gets its numbers? 0" trim? Fat chance. It’s no secret that Americans need to cut back on meat. While we Mostly from, or now eat more chicken than beef, we still eat too much red meat, with funding from, the beef and pork industries. Hmm... especially beef. That’s bad news for our health and for the planet. The USDA’s database has numbers for beef that has had People who eat more red meat—especially processed meat—have the fat around its edges trimmed down to just ⁄8” or 0”. a higher risk of colon cancer, heart disease, and stroke. (The pork industry never even says how much its cuts were trimmed.) And it doesn’t help that misleading information about meat or The USDA also has numbers for what’s called “separable poultry can trick even the most careful shoppers. Here’s what to lean.” That’s after scalpel-wielding technicians trim off the watch out for. “separable fat”—every bit of fat except marbling within the muscle. Missing labels? All that trimming (where do you keep your scalpel?) helps explain how the beef industry’s website can end up touting voluntarily, you’re 38 cuts of “lean” beef. The list even includes fatty cuts like stuck with a brochure New York strip steak and brisket. -

Variation of Amino Acids in White and Red Meat of Skipjack Tuna (Katsuwonus Pelamis) Caught from Arabian Sea

ISSN: 2319-8753 International Journal of Innovative Research in Science, Engineering and Technology Vol. 2, Issue 7, July 2013 VARIATION OF AMINO ACIDS IN WHITE AND RED MEAT OF SKIPJACK TUNA (KATSUWONUS PELAMIS) CAUGHT FROM ARABIAN SEA Remya James1, Vineeth Kumar T V2 Assistant Professor, Department of Zoology, St. Joseph‟s College for Women, Alappuzha, Kerala, India1 Research Scholar, Chemical Biology Laboratory, Rajiv Gandhi Centre for Biotechnology, Thiruvananthapuram, Kerala, India2 Abstract: Amino acid profile of the white and red (dark) meat in Katsuwonus pelamis, a tuna fish, caught from Arabian Sea in the month of January, was estimated using gas chromatography. There was no significant variation between red and white meat samples for the total percentage of essential and non-essential amino acids which constitute 52.3% and 47.7% respectively. Non essential amino acids asparagine and glutamine, and semi essential amino acid cysteine were not detected in both, red meat and white meat samples. Glutamate makes up approximately 13% in both samples which can be considered the highest. Certain individual amino acids, histidine, lysine and arginine showed variation between red and white meat samples. Keywords: red meat; white meat; amino acid; lysine; Katsuwonus pelamis I. INTRODUCTION Fish protein, like that of meat, is easily digestible and favorably complements dietary protein provided by beef, pork, chicken, cereals and legumes that are typically consumed in many developing countries (Winton and Winton, 2000). The protein in fish makes up complete protein source and tuna is a good source of high quality proteins. Tuna have white flesh and flesh that is pink to dark red. -

A Prospective Study of Red Meat Consumption and Type 2 Diabetes in Middle-Aged and Elderly Women the Women’S Health Study

Epidemiology/Health Services/Psychosocial Research ORIGINAL ARTICLE A Prospective Study of Red Meat Consumption and Type 2 Diabetes in Middle-Aged and Elderly Women The Women’s Health Study 1,2 1,2,4 YIQING SONG, MD JULIE E. BURING, SCD suspected as an important and indepen- 1,2,3 1,2 JOANN E. MANSON, MD, DRPH SIMIN LIU, MD, SCD dent contributor to risk of type 2 diabetes. This hypothesis was first generated based on the evidence from ecologic and mi- grant studies (2,3) and subsequently sup- OBJECTIVE — The aim of this study was to prospectively assess the relation between red ported by several cross-sectional and meat intake and incidence of type 2 diabetes. prospective studies of dietary patterns and diabetes (4–6). RESEARCH DESIGN AND METHODS — Over an average of 8.8 years, we evaluated Since the Seventh Day Adventists 37,309 participants in the Women’s Health Study aged Ն45 years who were free of cardiovas- Study first reported a positive association cular disease, cancer, and type 2 diabetes and completed validated semiquantitative food fre- between total meat intake and risk of type quency questionnaires in 1993. 2 diabetes in a population with a large proportion of vegetarians (7), few studies RESULTS — During 326,876 person-years of follow-up, we documented 1,558 incident have specifically assessed this relation be- cases of type 2 diabetes. After adjusting for age, BMI, total energy intake, exercise, alcohol intake, cigarette smoking, and family history of diabetes, we found positive associations between intakes tween meat consumption and incidence of red meat and processed meat and risk of type 2 diabetes. -

Biomarkers of Meat and Seafood Intake: an Extensive Literature Review Cătălina Cuparencu1*† , Giulia Praticó1†, Lieselot Y

Cuparencu et al. Genes & Nutrition (2019) 14:35 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12263-019-0656-4 REVIEW Open Access Biomarkers of meat and seafood intake: an extensive literature review Cătălina Cuparencu1*† , Giulia Praticó1†, Lieselot Y. Hemeryck2†, Pedapati S. C. Sri Harsha3†, Stefania Noerman4, Caroline Rombouts2, Muyao Xi1, Lynn Vanhaecke2, Kati Hanhineva4, Lorraine Brennan3 and Lars O. Dragsted1 Abstract Meat, including fish and shellfish, represents a valuable constituent of most balanced diets. Consumption of different types of meat and fish has been associated with both beneficial and adverse health effects. While white meats and fish are generally associated with positive health outcomes, red and especially processed meats have been associated with colorectal cancer and other diseases. The contribution of these foods to the development or prevention of chronic diseases is still not fully elucidated. One of the main problems is the difficulty in properly evaluating meat intake, as the existing self-reporting tools for dietary assessment may be imprecise and therefore affected by systematic and random errors. Dietary biomarkers measured in biological fluids have been proposed as possible objective measurements of the actual intake of specific foods and as a support for classical assessment methods. Good biomarkers for meat intake should reflect total dietary intake of meat, independent of source or processing and should be able to differentiate meat consumption from that of other protein-rich foods; alternatively, meat intake biomarkers should be specific to each of the different meat sources (e.g., red vs. white; fish, bird, or mammal) and/or cooking methods. In this paper, we present a systematic investigation of the scientific literature while providing a comprehensive overview of the possible biomarker(s) for the intake of different types of meat, including fish and shellfish, and processed and heated meats according to published guidelines for biomarker reviews (BFIrev). -

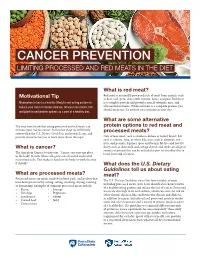

Cancer Prevention Limiting Processed and Red Meats in the Diet

bigstockphoto.com CANCER PREVENTION LIMITING PROCESSED AND RED MEATS IN THE DIET What is red meat? Motivational Tip Red meat is minimally processed cuts of meat from animals such as beef, veal, pork, deer, lamb, mutton, horse, and goat. Red meat Moderation is key to a healthy lifestyle and eating pattern to is a complete protein and provides iron, B vitamins, zinc, and reduce your risk for chronic disease. Choose lean meats, fish, all essential nutrients. While red meat is a complete protein, you should moderate the amount you consume in your diet. and plant-based protein options as a part of a healthy diet. What are some alternative You may have heard that eating processed and red meats can protein options to red meat and increase your risk for cancer. In this fact sheet we will briefly processed meats? review what the U.S. Dietary Guidelines and research says, and provide resources for you to learn more about the topic. Cuts of lean meat, such as skinless chicken or turkey breast; fish, such as salmon, tuna, or white fish; nuts, such as almonds, wal- nuts, and peanuts; legumes (peas and beans); fat-free and low-fat What is cancer? dairy, such as skim milk and cottage cheese; and seeds are all good sources of protein that can be included as part of a healthy diet to The American Cancer Society says, “Cancer can start any place lower your risk of cancer. in the body. It starts when cells grow out of control and crowd out normal cells. This makes it hard for the body to work the way it should.” What does the U.S. -

AICR Info on Red-Processed Meat

Red Meat NEED MORE HELP? Visit www.aicr.org for more information about diet, physical activity, weight and cancer prevention and survivorship. Or call 1-800-843- 8114 to request additional brochures, including: THE FACTS ABOUT THE RECOMMENDATION How much red meat can you eat? • 10 Ways to Reduce Your Cancer Risk Limit red meat AICR recommends eating no more than • The Cancer Fighters in Your Food Consume less than 18 oz. (cooked) of 18 ounces of red meat per week. This equals: • The New American Plate Red Meat & red meat a week. These and other brochures can be downloaded for free at up to 3 ounces (cooked), about the size • www.aicr.org. You can also visit the AICR Hotline online for answers • Red meat includes beef, pork and lamb. of a deck of cards, 6 times per week; or Processed Meat to your questions about diet and cancer, or call 1-800-843-8114 Monday–Friday, 9 am–5 pm ET. A registered dietitian will return your call. • up to 6 ounces (cooked) 3 times per week. American Institute for Cancer Research THE RESEARCH 1759 R Street, NW, P.O. Box 97167 Washington, DC 20090-7167 A review of all relevant research has shown that 1-800-843-8114 or 202-328-7744 diets high in red meat are linked with increased HOW TO CUT DOWN • Eating red meat and About AICR • risk of colorectal cancer. ON RED MEAT • processed meat increases OUR VISION: We want to live in a world where no one develops a • There seems to be an important threshold: preventable cancer. -

By-Products of Tuna Processing 00153 Rome, Italy Tel.: +39 06 5705 4744 Fax: +39 06 5705 3020 Volume 112

GLOBEFISH RESEARCH PROGRAMME Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations Products, Trade and Marketing Service Viale delle Terme di Caracalla By-products of tuna processing 00153 Rome, Italy Tel.: +39 06 5705 4744 Fax: +39 06 5705 3020 www.globefish.org Volume 112 By-products of tuna processing by Ms Esther Garrido Gamarro Mr Wanchai Orawattanamateekul Ms Joelyn Sentina Dr T. K. Srinivasa Gopal (July, 2013) The GLOBEFISH Research Programme is an activity initiated by FAO's Products, Trade and Marketing Branch, Fisheries and Aquaculture Policy and Economics Division, Rome, Italy and financed jointly by: - NMFS (National Marine Fisheries Service), Washington, DC, USA - Ministerio de Agricultura, Alimentación y Medio Ambiente, Subdirección General de Economía Pesquera, Madrid, Spain - Ministry of Food, Agriculture and Fisheries, Copenhagen, Denmark - European Commission, Directorate-General for Maritime Affairs and Fisheries, Brussels, EU - Norwegian Seafood Council, Tromsoe, Norway - FranceAgriMer, Montreuil-sous-Bois, Cedex, France - ASMI (Alaska Seafood Marketing Institute), USA - Sea Fish Industry Authority, United Kingdom Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, GLOBEFISH, Products, Trade and Marketing Branch, Fisheries and Aquaculture Policy and Economics Division Viale delle Terme di Caracalla, 00153 Rome, Italy - Tel: (39) 06570 54163 E-mail: [email protected]; [email protected] - Fax: (39) 06570 53020 - www.globefish.org The designations employed and the presentation of material in this information product do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) concerning the legal or development status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. -

Red and Processed Meat and Mortality in a Low Meat Intake Population

nutrients Article Red and Processed Meat and Mortality in a Low Meat Intake Population Saeed Mastour Alshahrani 1,2,* , Gary E. Fraser 1,3, Joan Sabaté 1,3 , Raymond Knutsen 1, David Shavlik 1, Andrew Mashchak 1 , Jan Irene Lloren 1 and Michael J. Orlich 1,3 1 School of Public Health, Loma Linda University, Loma Linda, CA 92354, USA; [email protected] (G.E.F.); [email protected] (J.S.); [email protected] (R.K.); [email protected] (D.S.); [email protected] (A.M.); [email protected] (J.I.L.); [email protected] (M.J.O.) 2 College of Applied Medical Sciences, King Khalid University, Abha 61421, Saudi Arabia 3 School of Medicine, Loma Linda University, Loma Linda, CA 92354, USA * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-310-270-7263 Received: 19 February 2019; Accepted: 8 March 2019; Published: 14 March 2019 Abstract: Associations of low-to-moderate consumption of red and processed meat with mortality would add to the evidence of possible adverse effects of these common foods. This study aims to investigate the association of red and processed meat intake with mortality. The Adventist Health Study-2 (AHS-2) is a prospective cohort study of ~96,000 Seventh-day Adventist men and women recruited in the US and Canada between 2002 and 2007. The final analytic sample after exclusions was 72,149. Cox proportional hazards regression was used and hazard ratios (HR) and confidence intervals (CI) were obtained. Diet was assessed by a validated quantitative food frequency questionnaire (FFQ), calibrated using six 24-h dietary recalls. -

Red Meat and Processed Meat Volume 114

RED MEAT AND PROCESSED MEAT volume 114 This publication represents the views and expert opinions of an IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans, which met in Lyon, 6–13 October 2015 LYON, FRANCE - 2018 iarc monographs on the evaluation of carcinogenic risks to humans 3. CANCER IN EXPERIMENTAL ANIMALS No long-term bioassays of full carcino- and colon/caecum. Mice fed the modified diet genicity with red meat or processed meat were containing beef had a greater number of tumours available to the Working Group; however, the in the small intestine compared with mice fed Working Group considered a variety of animal the control diet, with the difference being signif- bioassays. icant in the distal small intestine (P = 0.009) (Mutanen et al., 2000). [The Working Group 3.1 Mouse noted that the tumour data were confounded by the fact that the beef diet contained considerably See Table 3.1 more fat (274.8 g/kg diet) than the control diet (70.0 g/kg diet). The control diet contained 3.1.1 Red meat calcium at a concentration of 5.1 g/kg diet, and did not contain fibre; however, there was no Groups of seven to nine male C57Bl/6J- increase in the incidence of tumours of the small ApcMin mice (age, 6–8 weeks), a strain primarily intestine in a separate non-fibre, high-fat group.] susceptible to spontaneous adenomas of the Groups of six to eight male and six to eight small intestine, were fed American Institute female C57Bl/6J-ApcMin mice (age, 5 weeks) were of Nutrition (AIN-93G)–based diets, either a transferred from a standard rodent chow diet semisynthetic control diet or a modified diet in and fed AIN-93G–based diets, either a semi- which casein, the protein source, was replaced synthetic control diet or a modified diet in which with beef (24%), for 5–6 weeks.