A North Sea Diary, 1914-1918 / Commander

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

South Africa's D-Day Veterans

Scientia Militaria, South African Journal of Military Studies, Vol 24, Nr 2, 1994. http://scientiamilitaria.journals.ac.za SOUTH AFRICA'S D-DAY VETERANS Cdr w.M. Bisset SA Naval Museum, Simon's Town Although some 657 members of the South African Union Defence Forces served in North West Europe between D-Day on 6 June 1944 and VE-Day on 8 May 1945, it would seem that relatively few of them were present on D-Day. South Africa's main contributions to the war effort were made in Ethiopia, Madagascar, the Western Desert, Italy and on her own home front which included the vital Cape Sea Route. In volume two of his biography of General ice records are not readily available it is not Smuts" Sir Keith Hancock has written: "The possible to compile a definitive article on this Cape of Good Hope lived up to. its name and topic at this stage. Even the records of our assumed once again its historic primacy in oce- own personnel seconded to the British forces anic strategy. Without the Cape route, the seldom reveal whether the servicemen con- Commonwealth could hardly have survived the cerned served on D-Day or not. War; without the Commonwealth, the Russians and Americans could hardly have won it". South Africans were present at Dunkirk and Dieppe so it was fitting that they should return In addition to those who served in the Union to France when the tide turned. Defence Forces there were many South Afri- cans who were serving in the British or Com- The South African naval officers and ratings in monwealth forces or who joined up where they the invasion fleet were the largest group of were on the outbreak of war. -

K a L E N D E R- B L Ä T T E R

- Simon Beckert - K A L E N D E R- B L Ä T T E R „Nichts ist so sehr für die „gute alte Zeit“ verantwortlich wie das schlechte Gedächtnis.“ (Anatole France ) Stand: Januar 2016 H I N W E I S E Eckig [umklammerte] Jahresdaten bedeuten, dass der genaue Tag des Ereignisses unbekannt ist. SEITE 2 J A N U A R 1. JANUAR [um 2100 v. Chr.]: Die erste überlieferte große Flottenexpedition der Geschichte findet im Per- sischen Golf unter Führung von König Manishtusu von Akkad gegen ein nicht bekanntes Volk statt. 1908: Der britische Polarforscher Ernest Shackleton verlässt mit dem Schoner Nimrod den Ha- fen Lyttelton (Neuseeland), um mit einer Expedition den magnetischen Südpol zu erkunden (Nimrod-Expedition). 1915: Die HMS Formidable wird in einem Nachtangriff durch das deutsche U-Boot SM U 24 im Ärmelkanal versenkt. Sie ist das erste britische Linienschiff, welches im Ersten Weltkrieg durch Feindeinwirkung verloren geht. 1917: Das deutsche U-Boot SM UB 47 versenkt den britischen Truppentransporter HMT In- vernia etwa 58 Seemeilen südöstlich von Kap Matapan. 1943: Der amerikanische Frachter Arthur Middleton wird vor dem Hafen von Casablanca von dem deutschen U-Boot U 73 durch zwei Torpedos getroffen. Das zu einem Konvoi gehörende Schiff ist mit Munition und Sprengstoff beladen und versinkt innerhalb einer Minute nach einer Explosion der Ladung. 1995: Die automatische Wellenmessanlage der norwegischen Ölbohrplattform Draupner-E meldet in einem Sturm eine Welle mit einer Höhe von 26 Metern. Damit wurde die Existenz von Monsterwellen erstmals eindeutig wissenschaftlich bewiesen. —————————————————————————————————— 2. JANUAR [um 1990 v. Chr.]: Der ägyptische Pharao Amenemhet I. -

The Naval Engineer

THE NAVAL ENGINEER SPRING/SUMMER 2019, VOL 06, EDITION NO.2 All correspondence and contributions should be forwarded to the Editor: Welcome to the new edition of TNE! Following the successful relaunch Clare Niker last year as part of our Year of Engineering campaign, the Board has been extremely pleased to hear your feedback, which has been almost entirely Email: positive. Please keep it coming, good or bad, TNE is your journal and we [email protected] want to hear from you, especially on how to make it even better. By Mail: ‘..it’s great to see it back, and I think you’ve put together a great spread of articles’ The Editor, The Naval Engineer, Future Support and Engineering Division, ‘Particularly love the ‘Recognition’ section’ Navy Command HQ, MP4.4, Leach Building, Whale Island, ‘I must offer my congratulations on reviving this important journal with an impressive Portsmouth, Hampshire PO2 8BY mix of content and its presentation’ Contributions: ‘..what a fantastic publication that is bang up to date and packed full of really Contributions for the next edition are exciting articles’ being sought, and should be submitted Distribution of our revamped TNE has gone far and wide. It is hosted on by: the MOD Intranet, as well as the RN and UKNEST webpages. Statistics taken 31 July 2019 from the external RN web page show that there were almost 500 visits to the TNE page and people spent over a minute longer on the page than Contributions should be submitted average. This is in addition to all the units and sites that received almost electronically via the form found on 2000 hard copies, those that have requested electronic soft copies, plus The Naval Engineer intranet homepage, around 700 visitors to the internal site. -

'The Admiralty War Staff and Its Influence on the Conduct of The

‘The Admiralty War Staff and its influence on the conduct of the naval between 1914 and 1918.’ Nicholas Duncan Black University College University of London. Ph.D. Thesis. 2005. UMI Number: U592637 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U592637 Published by ProQuest LLC 2013. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 CONTENTS Page Abstract 4 Acknowledgements 5 Abbreviations 6 Introduction 9 Chapter 1. 23 The Admiralty War Staff, 1912-1918. An analysis of the personnel. Chapter 2. 55 The establishment of the War Staff, and its work before the outbreak of war in August 1914. Chapter 3. 78 The Churchill-Battenberg Regime, August-October 1914. Chapter 4. 103 The Churchill-Fisher Regime, October 1914 - May 1915. Chapter 5. 130 The Balfour-Jackson Regime, May 1915 - November 1916. Figure 5.1: Range of battle outcomes based on differing uses of the 5BS and 3BCS 156 Chapter 6: 167 The Jellicoe Era, November 1916 - December 1917. Chapter 7. 206 The Geddes-Wemyss Regime, December 1917 - November 1918 Conclusion 226 Appendices 236 Appendix A. -

Hms Southampton 1981-1983

Introduction - HMS SOUTHAMPTON — the sixth — was commissioned almost two years ago on 31st October, 1981. Seven months later, in June 1982, she sailed for the Falkland Islands Total Exclusion Zone and returned to UK as the South Atlantic winter ended and the next English winter was beginning. This year has seen a similar pattern with another 5-½ month South Atlantic deployment — once more covering the English summer. You may wonder how it is possible to produce a " Full Commission " book worth reading about a ship that in her first two years has seen five winters and no summers, two long South Atlantic deployments and only two short foreign runs (one of which was very bad!). The worthy fact is that it is people not programmes that primarily make for a happy and successful ship — although I am amongst the first to agree that the latter are important. Individual ships have an uncanny knack of retaining their character and personality from build and then passing these on through successive ship's companies. HMS Southamption will always be a friendly, cheerful and successful ship and we are right to record her early life and ship's company. She has covered over 83,000 miles in her first two years — almost twice as far as the average pre-Corporate operational frigate or destroyer in the same timescale. This book is your record of a slice of your life — mainly to remind you of the characters and personalities with whom you served. For me, personally, this book will always remind me with immense pleasure and much reassurance of the thoroughly supportive and cheerful team with whom I was privileged to serve after the extraordinary events of last year. -

Scuily Jwly I>V <X- Vtry Povirt Ifahs W Iflv Fke- C<R\Rtr A^D/ -Twts Furit/Yuscnuk Pxuqfy/ Wx^/R-Mj

ScuiLy JWLy i>v <x- vtry povirt ifaHs w iflv fKe- c<r\rtr a^d/ -tWts furit/yusCnuk p xu q fy / wX^/R-mj. Ai^o-co pixsbM't- W<x-y fc>ee*v caM-otaA o-ms crv^y oj-jW t' piUjty. OjWvrvA^y LA iy towipLtfai THE COMMUNICATOR 97 ®fje ©[rector of tf)e S ign al ©totsC'on anb fji£ H>taff all Communicators a imppp Christmas anb p e st 32)isljes for tlje J8eto gear. I have sent the following letter to Admiral Mountbatten on his appointment a3 Commander-in-Chief, Mediterranean. “All of us in Mercury were delighted to hear of your appointment as Com mander-in-Chief, Mediterranean, and send you our heartiest congratulations. “We are very proud that the most important appointment in command of a Fleet will now be held by a Signal Officer and that his second in command is also a Signal @fficer ” J. G. T. In c u s , Captain. EDITORIAL The Editorial Staff has been reinforced by the her, on behalf of all of us, every success in civilian addition of two ratings, the one to represent Chief life. We will be delighted to give her a good reference. and Petty Officers, the other to represent Leading Two more requests: Could individual subscribers rates and below. This is not Empire Building. It let us know when they change their address? Finally, fulfils a need which has been felt for some time, if you happen to buy something as a result of one and as a result it is hoped that a well-balanced of our advertisements, please say so, not to us, but opinion will be available. -

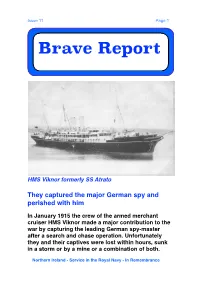

Brave Record Issue 11

Issue 11 Page !1 Brave Report HMS Viknor formerly SS Atrato They captured the major German spy and perished with him In January 1915 the crew of the armed merchant cruiser HMS Viknor made a major contribution to the war by capturing the leading German spy-master after a search and chase operation. Unfortunately they and their captives were lost within hours, sunk in a storm or by a mine or a combination of both. Northern Ireland - Service in the Royal Navy - In Remembrance Issue 11 Page !2 The ship’s Commanding Officer, E O Ballantyne, had been informed by Lord Fisher that he was to search for and apprehend the SS Bergensfjord - a Norwegian owned and neutral ship. Information had been received from British intelligence sources that persons taken aboard the ship in New York under the guise of being neutral citizens were in fact German reservists. This was quite a challenge to present to what in reality was a makeshift warship. Viknor was a civilian ship hastily prepared for war, and manned mainly by members of the Royal Naval Reserve, including twenty-five seamen of the Newfoundland Division of the RNR. In their search and apprehend action the ship’s company proved that they were fit for role. The Viknor which was only able to do seventeen knots had headed out to the North Sea as Admiral Jellico wanted it to strengthen the blockade of Germany by the northern patrol. On Friday 8th December the message was flashed to the fleet that SS Bergensfjord should be captured at all costs. -

THE BATTLE of MADAGASCAR: OPERATIONS IRONCLAD & STREAM LINE JANE Belligerents

THE BATTLE OF MADAGASCAR: OPERATIONS IRONCLAD & STREAM LINE JANE DATE: MAY 05 – NOV 06 1942 Belligerents United Kingdom Vichy France India Madagascar Northern Rhodesia Japan (naval) Southern Rhodesia Tanganyika South Africa Australia (naval) Netherlands (naval) Although many Free French were now fighting with the British, the Vichy regime in France was a different proposition. The French had allowed the Japanese into French Indo-China, a move that had given them access to Malaya and Singapore. Now it was feared that the Japanese would move into the huge natural deep water port of Diego Suarez, on the northern tip of the French colony of Madagascar. Such a move would give the Japanese a dominant position in the Indian Ocean and threaten the convoy route running up East Africa to Egypt. A pre-emptive invasion of Madagascar was therefore launched by the British. On May 5 1941, Operation Ironclad saw troops land near Diego Suarez on the north western tip of the island in an attempt to capture the port from the rear. The first wave saw the British 29th Infantry Brigade and No. 5 Commando landed. Follow-up waves were by two brigades of the 5th Infantry Division and the Royal Marines. All were carried ashore by landing craft to Courrier Bay and Ambararata Bay, just west of Diego Suarez. A diversionary attack was staged to the east. The beach landings met with virtually no resistance and these troops seized Vichy coastal batteries and barracks. After landing, the Courier Bay force (17th Infantry Brigade) met with toiling through mangrove swamp and thick bush before taking the town of Diego Suarez and taking a hundred prisoners. -

Rofworld •WKR II

'^"'^^«^.;^c_x rOFWORLD •WKR II itliiro>iiiiii|r«trMit^i^'it-ri>i«fiinit(i*<j|yM«.<'i|*.*>' mk a ^. N. WESTWOOD nCHTING C1TTDC or WORLD World War II was the last of the great naval wars, the culmination of a century of warship development in which steam, steel and finally aviation had been adapted for naval use. The battles, both big and small, of this war are well known, and the names of some of the ships which fought them are still familiar, names like Bismarck, Warspite and Enterprise. This book presents these celebrated fighting ships, detailing both their war- time careers and their design features. In addition it describes the evolution between the wars of the various ship types : how their designers sought to make compromises to satisfy the require - ments of fighting qualities, sea -going capability, expense, and those of the different naval treaties. Thanks to the research of devoted ship enthusiasts, to the opening of government archives, and the publication of certain memoirs, it is now possible to evaluate World War II warships more perceptively and more accurately than in the first postwar decades. The reader will find, for example, how ships in wartime con- ditions did or did not justify the expecta- tions of their designers, admiralties and taxpayers (though their crews usually had a shrewd idea right from the start of the good and bad qualities of their ships). With its tables and chronology, this book also serves as both a summary of the war at sea and a record of almost all the major vessels involved in it. -

Ship-Breaking.Com 2012 Bulletins of Information and Analysis on Ship Demolition, # 27 to 30 from January 1St to December 31St 2012

Ship-breaking.com 2012 Bulletins of information and analysis on ship demolition, # 27 to 30 From January 1st to December 31st 2012 Robin des Bois 2013 Ship-breaking.com Bulletins of information and analysis on ship demolition 2012 Content # 27 from January 1st to April 15th …..……………………….………………….…. 3 (Demolition on the field (continued); The European Union surrenders; The Senegal project ; Letters to the Editor ; A Tsunami of Scrapping in Asia; The END – Pacific Princess, the Love Boat is not entertaining anymore) # 28 from April 16th to July 15th ……..…………………..……………….……..… 77 (Ocean Producer, a fast ship leaves for the scrap yard ; The Tellier leaves with honor; Matterhorn, from Brest to Bordeaux ; Letters to the Editor ; The scrapping of a Portuguese navy ship ; The India – Bangladesh pendulum The END – Ocean Shearer, end of the cruise for the sheep) # 29 from July 16th to October 14th ....……………………..……………….……… 133 (After theExxon Valdez, the Hebei Spirit ; The damaged ship conundrum; Farewell to container ships ; Lepse ; Letters to the Editor ; No summer break ; The END – the explosion of Prem Divya) # 30 from October 15th to December 31st ….………………..…………….……… 197 (Already broken up, but heading for demolition ; Demolition in America; Falsterborev, a light goes out ; Ships without place of refuge; Demolition on the field (continued) ; Hong Kong Convention; The final 2012 sprint; 2012, a record year; The END – Charlesville, from Belgian Congo to Lithuania) Global Statement 2012 ……………………… …………………..…………….……… 266 Bulletin of information and analysis May 7, 2012 on ship demolition # 27 from January 1 to April 15, 2012 Ship-breaking.com An 83 year old veteran leaves for ship-breaking. The Great Lakes bulker Maumee left for demolition at the Canadian ship-breaking yard at Port Colborne (see p 61). -

Guns Blazing! Newsletter of the Naval Wargames Society No

All Guns Blazing! Newsletter of the Naval Wargames Society No. 220 – FEBRUARY 2013 EDITORIAL Don’t let the same people do more than their fair share each month. Articles for AGB and Battlefleet are welcome from all Members. Review a book, or let us know your opinion on a set of Rules etc. Any historical period actual or “what if” scenario. The Naval Wargames Society has had an invite to put on a game at Colours this year (14th and 15th Sept at Newbury, Berkshire). Anyone interested in helping to run a game on behalf of the NWS or suggestions on the game to run, please contact Simon Stokes reasonably soon as we need to plan the game and submit the entry form. Welcome to new members, Phil Russell, Jeff Chorney, Michael Clark, Al McDonald, John Collison, Everett Sharp, Mark Gardiner, Charles Carter, Mark Saunders, Sylvain Rheault and Warren Greene. (USA and Canada well represented.) http://www.beiyang.org/dingyuan/bd.htm Control and click to follow this link supplied by new NWS Member Everett Sharp. 10 Years of pictures showing building a high standard replica Ship. http://www.lanacion.com.ar/1547741-buscan-evitar-el-hundimiento-del-un-buque-de-la- armada Thanks to Stuart, for this link which shows that water should never be under estimated. The Royal Navy came close to losing HMS NOTTINGHAM several years ago now when She hit rocks near Australia. More recently HMS ENDURANCE came close to sinking when She sprung a leak in Antarctic waters. View the trouble that a broken 6 inch pipe caused for the Argentine Type 42 Destroyer, Santisima Trinadad. -

1892-1929 HM Ships

HEADING RELATED YEAR EVENT Year/Page Aboukir 1812 NGS Medal for Gulf of Rga 1919/183 Aboukir 1913 Award of Humane Society medal to Maj Boyce 1913/137 Aboukir 1914 RM Casualties 1914/196 Africa 1919 Epidemic pf 'flu, officers man boats 1919/28 AFRICA STATION 1924 Landing Exercises 1924/68 AFRICA STATION 1924 Ships at Durban for Centenary Celebrations 1924/84 Agamemnon 1915 RM Casualties, Dardanelles 1915/75 RM at Budapest, Odessa, 1920/ RM Cutters Ajax 1919 Crew 1920/10, 58; 1921/171* Alacrity 1907 Promoptitude of Sgt House in sampan 1907/39 Albemarle 1905 Loader competition 1905/16* Alcantara 1916 RM casualties on loss of ship 1916/89 Alexander 1794 Article - "Captured buy the FRench" 1921/180 Ambrose 1921 In China 1921/27 See also WEST INDIES AMERICA & W INDIES SQUADRON 1928 Articles 1928/60, 81, Amethyst 1915 RM casualties, Dardanelles 1915/74 Amphion 1914 First ship engaged in WWI 1921/180 Amphion 1914 Sunk; RM casualties 1914/149, 157 Anson 1899 Shooting Team 1899/221* Archer 1892 Incident in Yokohama Vol 1/49 See also Atlantic Fleet; News; Rescuing Hood's Argus Atlantic 1924 picquet boat, 1928 1928/259* Argus 1925 Articles 1925/3 Argus 1928 Articles 1928/259, 288. Argus 1929 Articles 1929/23, 59, 125, 321, Argus 1929 Articles 1929/23, 59, 125, 321. ATLANTIC FLEET 1923 Cruise along South and South East Coast 1923/118 ATLANTIC FLEET 1924 Ships with RM Detachments 1924/178 ATLANTIC FLEET 1926 Dispositions - General Strike 1926/135 ATLANTIC FLEET 1926 Combined Operations Exercise 1926/212, 223 ATLANTIC FLEET 1928 March through Gibraltar 1928/74, 75, 76 ATLANTIC FLEET 1928 Articles 1928/2, 54, 74, 96, E36 ATLANTIC FLEET 1929 Articles 1929/59, 153, 187, ATLANTIC FLEET 1929 Sports at Gibraltar 1929/95, Visit to France, winners tug-o'-war; Alexandria, Barham 1919 1927 1919/84, 88*; 1927/160 Barham 1926 Articles 1926/137 1927/160, 179, 197, 218, Barham 1927 Articles 238.