How Celtic Culture Invented Southern Literature. James P. Cantrell

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Studies in Celtic Languages and Literatures: Irish, Scottish Gaelic and Cornish

e-Keltoi: Journal of Interdisciplinary Celtic Studies Volume 9 Book Reviews Article 7 1-29-2010 Celtic Presence: Studies in Celtic Languages and Literatures: Irish, Scottish Gaelic and Cornish. Piotr Stalmaszczyk. Łódź: Łódź University Press, Poland, 2005. Hardcover, 197 pages. ISBN:978-83-7171-849-6. Emily McEwan-Fujita University of Pittsburgh Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.uwm.edu/ekeltoi Recommended Citation McEwan-Fujita, Emily (2010) "Celtic Presence: Studies in Celtic Languages and Literatures: Irish, Scottish Gaelic and Cornish. Piotr Stalmaszczyk. Łódź: Łódź University Press, Poland, 2005. Hardcover, 197 pages. ISBN:978-83-7171-849-6.," e-Keltoi: Journal of Interdisciplinary Celtic Studies: Vol. 9 , Article 7. Available at: https://dc.uwm.edu/ekeltoi/vol9/iss1/7 This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by UWM Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in e-Keltoi: Journal of Interdisciplinary Celtic Studies by an authorized administrator of UWM Digital Commons. For more information, please contact open- [email protected]. Celtic Presence: Studies in Celtic Languages and Literatures: Irish, Scottish Gaelic and Cornish. Piotr Stalmaszczyk. Łódź: Łódź University Press, Poland, 2005. Hardcover, 197 pages. ISBN: 978-83- 7171-849-6. $36.00. Emily McEwan-Fujita, University of Pittsburgh This book's central theme, as the author notes in the preface, is "dimensions of Celtic linguistic presence" as manifested in diverse sociolinguistic contexts. However, the concept of "linguistic presence" gives -

Gaelic Scotland in the Colonial Imagination

Gaelic Scotland in the Colonial Imagination Gaelic Scotland in the Colonial Imagination Anglophone Writing from 1600 to 1900 Silke Stroh northwestern university press evanston, illinois Northwestern University Press www .nupress.northwestern .edu Copyright © 2017 by Northwestern University Press. Published 2017. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication data are available from the Library of Congress. Except where otherwise noted, this book is licensed under a Creative Commons At- tribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. In all cases attribution should include the following information: Stroh, Silke. Gaelic Scotland in the Colonial Imagination: Anglophone Writing from 1600 to 1900. Evanston, Ill.: Northwestern University Press, 2017. For permissions beyond the scope of this license, visit www.nupress.northwestern.edu An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libraries working with Knowledge Unlatched. KU is a collaborative initiative designed to make high-quality books open access for the public good. More information about the initiative and links to the open-access version can be found at www.knowledgeunlatched.org Contents Acknowledgments vii Introduction 3 Chapter 1 The Modern Nation- State and Its Others: Civilizing Missions at Home and Abroad, ca. 1600 to 1800 33 Chapter 2 Anglophone Literature of Civilization and the Hybridized Gaelic Subject: Martin Martin’s Travel Writings 77 Chapter 3 The Reemergence of the Primitive Other? Noble Savagery and the Romantic Age 113 Chapter 4 From Flirtations with Romantic Otherness to a More Integrated National Synthesis: “Gentleman Savages” in Walter Scott’s Novel Waverley 141 Chapter 5 Of Celts and Teutons: Racial Biology and Anti- Gaelic Discourse, ca. -

Celtic Studies (CLT)

This is a copy of the 2021-2022 catalog. CLT 2110 The Music of the Celtic Peoples (3 units) CELTIC STUDIES (CLT) Survey of the traditional music of Ireland, Gaelic Scotland, Wales, Brittany, Cornwall, Isle of Man, Galicia as well as the Celtic diaspora of Canada. CLT 1100 Scottish Gaelic Language and Culture I (3 units) Song, instruments, and performance techniques will be studied, in an Survey of the medieval and modern history of Gaelic Scotland. Aspect historical as well as a contemporary context. of contempory Scottish Gaelic culture. Basic course in Modern Scottish Course Component: Lecture Gaelic. CLT 2130 Early Celtic Literature (3 units) Course Component: Lecture Study of the poetry, sagas, myths, stories and traditions of early and CLT 1101 Scottish Gaelic Language and Culture II (3 units) medieval Ireland, Scotland, Wales and Brittany. Further study of the structures and vocabulary of Modern Scottish Gaelic. Course Component: Lecture Introductory survey of song and literature from the 17th to the 20th No knowledge of Celtic languages required. century. CLT 2131 Medieval Celtic Literature (3 units) Course Component: Lecture Study of late medieval writings from Ireland, Wales and Scotland; the Prerequisite: CLT 1100. Fenian Cycle of prose tales from Ireland; Dafydd ap Gwilym and the Welsh CLT 1110 Irish Language and Culture I (3 units) poetic tradition; Scottish Gaelic poetry of the 16th century. Survey of medieval and modern history of Gaelic Ireland. Aspects of Course Component: Lecture contemporary Irish Gaelic culture. Basic course in Modern Irish. CLT 2150 Celtic Christianity (3 units) Course Component: Lecture Introduction to early medieval Christianity in Celtic lands: Celtic saints CLT 1111 Irish Language and Culture II (3 units) and monasticism, pilgrimage, the theologies of Eriugena and Pelagius, Further study of the structures and vocabulary of Modern Irish. -

1 the Celts and Their Languages

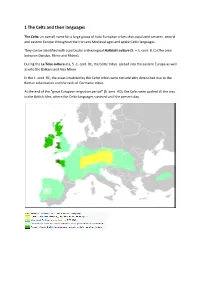

1 The Celts and their languages The Celts: an overall name for a large group of Indo-European tribes that populated western, central and eastern Europe throughout the Iron and Medieval ages and spoke Celtic languages. They can be identified with a particular archeological Hallstatt culture (8. – 5. cent. B. C) (The area between Danube, Rhine and Rhône). During the La Tène culture era, 5.-1. cent. BC, the Celtic tribes spread into the eastern Europe as well as into the Balkans and Asia Minor. In the 1. cent. BC, the areas inhabited by the Celtic tribes were considerably diminished due to the Roman colonization and the raids of Germanic tribes. At the end of the “great European migration period” (6. cent. AD), the Celts were pushed all the way to the British Isles, where the Celtic languages survived until the present day. The oldest roots of the Celtic languages can be traced back into the first half of the 2. millennium BC. This rich ethnic group was probably created by a few pre-existing cultures merging together. The Celts shared a common language, culture and beliefs, but they never created a unified state. The first time the Celts were mentioned in the classical Greek text was in the 6th cent. BC, in the text called Ora maritima written by Hecateo of Mileto (c. 550 BC – c. 476 BC). He placed the main Celtic settlements into the area of the spring of the river Danube and further west. The ethnic name Kelto… (Herodotus), Kšltai (Strabo), Celtae (Caesar), KeltŇj (Callimachus), is usually etymologically explainedwith the ie. -

The Gaelic Bards : and Original Poems

GÀEIvICW zn. THE GAELIC BAUDS ORIGINAL POEMS. a%|) ^M^rmoi^^ix;^^^^ The Gtaelic Bards, OEIGINAL POEMS, THOMAS PATTISON. EDITED, WITH A BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCH AND NOTES, BY THE Rev. JOHN GEORGE MAONEILL, CAWDOR. SECOND EDITION GLASGOW: ARCHIBALD SINCLAIR, PRINTER & PUBLISHER, 62 ARGYLE STREET. 18 90. ARCHIBALD SINCLAIR, PRINTER AND PUBLISHER, ARGYLK STREET, GLASGOW. PREFACE TO THE SECOND EDITION. The First Edition of ''The Gaelic Bards" having been exhausted^ a new edition was called for. The work, in its two sections of Modem Gaelic Bards, and of Ancient Gaelic Bards is practically unchanged. A few vague and uninteresting original poems have been omitted, but other characteristic and popular pieces, such as " Captain Gorrie's Ride," "The Praise of Islay," and "Haste from the Window," have been inserted. Some distinct additions have been made to the present edition, in the shape of a biographical sketch, and appended illustrative notes by the Editor. A portrait of the Author is also given. In introducing the Second Edition to the public, the Publisher and the Editor are confident that it will be welcomed by their brother Celts at home and abroad, as an acceptable contribution to the ever increasing important department of Celtic Literature. The labour bestowed on this Edition by the Publisher and the Editor, was ungrudgingly given in the midst of the whirl and worry of daily duty. — PREFATORY NOTICE TO THE FIRST EDITION. Thomas Pattison was a native of Islay, He was designed for the Church, and after receiving a fair elementary education at the Parish School of Bow- more, was sent to the University of Edinburgh, and afterwards to that of Glasgow. -

The Literature of the Celts Magnus Maclean Ll.D

THE LITERATURE OF THE CELTS MAGNUS MACLEAN LL.D. BLACICIE AND SON LIMITED Printed in Great Britain THE LITERATURE OF THE CELTS THE LITERATURE OF THE CELTS BY MAGNUS MACLEAN M.A., D.Sc, LL.D. NE W EDITION BLACKIE AND SON LIMITED 50 OLD BAILEY, LONDON; GLASGOW, BOMBAY 1926 PREFACE Celtic studies have grown apace within recent years. The old scorn, the old apathy and neglect are visibly giving way to a lively wonder and interest as the public gradually realise that scholars have lighted upon a literary treasure hid for ages. This new enthusiasm, generated in great part on the Continent—in Germany, France, and Italy, as well as in Britain and Ireland, has already spread to the northern nations—to Denmark, Sweden, and Norway, and is now beginning to take root in America. A remarkable change it certainly presents from the days when Dr. Johnson affirmed that there was not in all the world a Gaelic MS. one hundred years old; and the documents were so derelict and forgotten, so little known and studied, that though this prince of letters travelled in the Highlands expressly to satisfy himself, Celtic knowledge of the existing materials and Celtic studies were so deficient that they proved wholly inadequate to the task of disproving his bold statement. It was left to the scholarship of the nineteenth century to unearth the ancient treasures and to show that Gaelic was a literary language long before English literature came into existence, and that there are still extant Celtic-Latin MSS. almost as old as the very oldest codexes of the Bible. -

Celtic Literature

Celtic Literature Matthew Arnold Celtic Literature Table of Contents Celtic Literature........................................................................................................................................................1 Matthew Arnold.............................................................................................................................................1 INTRODUCTION.........................................................................................................................................1 I....................................................................................................................................................................10 II...................................................................................................................................................................14 III..................................................................................................................................................................24 IV.................................................................................................................................................................26 V...................................................................................................................................................................30 VI.................................................................................................................................................................35 i Celtic Literature -

Cornish Language and Literature: a Brief Introduction

ACTA UNI VERSITATIS LODZIENSIS FOLIA LITTER ARIA ANGLICA 3, 1999 Piotr Stalmaszczyk CORNISH LANGUAGE AND LITERATURE: A BRIEF INTRODUCTION Cornish is a South-Western British Celtic language, closely related to Breton and Welsh. In the period between 600 and 800 AD the westward movement of Anglo-Saxon peoples separated the Celts of Strathclyde, Cumbria, Wales, and the Cornish peninsula. The dialects of Common British1 developed into Primitive Welsh, Primitive Cornish and Primitive Breton, the earliest stages of separate languages spoken in Wales, Cornwall, and Brittany, respectively. The further history of Cornish is conventionally divided into Old Cornish (from its beginnings to the end of the twelfth century), Middle Cornish (1200-1600) and Late Cornish (1600-1800). The last phase is also known as Traditional Cornish, in contrast to Modern Cornish, the result of various contemporary attempts at reviving the language.2 1 This reconstructed form of the ancestral language is also called Old British, Brittonic or Brythonic, sometimes the names are used interchangeably, in other cases, however, they refer to distinct phases in the development of the language. The most important study on the early linguistic history of the British Isles remains the monumental work by Kenneth H. Jackson, Language and History in Early Britain (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1953, reprinted 1994, Dublin: The Four Courts Press). Cornish language and literature is discussed by Peter Berresford Ellis in The Cornish Language and its Literature (London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1974); Brian Murdoch provides the most comprehensive account of the literature to date in Cornish Literature (Cambridge: D. S. Brewer, 1993); cf. -

Translated Drama in Gaelic in Scotland to C.1950 Sìm Innes

Translated Drama in Gaelic in Scotland to c.19501 Sìm Innes, University of Glasgow Introduction In 1893 Catrìona NicIlleBhàin Ghrannd / Katherine Whyte Grant outlined her motivation for translating Friedrich Schiller’s Wilhelm Tell (1804) from German into Scottish Gaelic as follows: I longed to give my Highland countrymen a delightful taste of the good things stored up in the literature of other nations, of people whom we consider as alien and foreign, yet with feelings and sympathies closely akin to our own. We need to have our sympathies extended; we need to get out of the few narrow grooves in which our thoughts are apt to run; to get above ourselves, so that our petty individuality may be merged in the good of the whole. Grant’s expression of the potential of translation would accord well with commentary on translation of drama into Scots. John Corbett notes that, ‘If native drama affords the opportunity for the ethos of a community to be represented, positively or negatively, on stage, then translated drama gives an audience the chance to encounter ‘otherness’’. (2011: 95-96) Of course, literary translation, particularly, in minority language situations, can also act as a form of activism. Maria Tymoczko reminds us that Translation is not simply a meeting of a self and an other, mediated by a translator. Often it is a way for a heterogeneous culture or nation to define itself, to come to know itself, to come to terms with its own hybridity… Thus, translators have a potentially activist role. (2010: 197-198) Grant’s political agency as a Gaelic translator and her reference to ‘feelings and sympathies closely akin to our own’, combined with her allusion to the opportunity for community development, will all be explored in further detail below. -

Celts in Hiding: the Search for Celtic Analogues in "Beowulf"

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1997 Celts in Hiding: The Search for Celtic Analogues in "Beowulf" Vincent Gabriel Passanisi College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the English Language and Literature Commons, and the Medieval Studies Commons Recommended Citation Passanisi, Vincent Gabriel, "Celts in Hiding: The Search for Celtic Analogues in "Beowulf"" (1997). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539626118. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-azmc-8393 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CELTS IN HIDING: THE SEARCH FOR CELTIC ANALOGUES IN BEOWULF A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of English The College of William and Mary in Virginia In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts by Vincent Passanisi 1997 APPROVAL SHEET This thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Author Approved, April 1997 Monica Potkay Paula Blank John Conlee DEDICATION To Allison and Sam ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to thank Professor Monica Potkay for her guidance, patience, and encouragement. I consider myself very fortunate to have had such a skillful editor and critic for my advisor. I could not have asked for a more knowledgeable nor insightful mentor. -

Celtic Literatures in the Twentieth Century

Celtic Literatures in the Twentieth Century Edited by Séamus Mac Mathúna and Ailbhe Ó Corráin Assistant Editor Maxim Fomin Research Institute for Irish and Celtic Studies University of Ulster Languages of Slavonic Culture Moscow, 2007 CONTENTS Introduction . .5 . Séamus Mac Mathúna and Ailbhe Ó Corráin Twentieth Century Irish Prose . 7 Alan Titley Twentieth Century Irish Poetry: Dath Géime na mBó . 31 Diarmaid Ó Doibhlin Twentieth Century Scottish Gaelic Poetry . 49 Ronald Black Twentieth Century Welsh Literature . 97 Peredur Lynch Twentieth Century Breton Literature . 129 Francis Favereau Big Ivor and John Calvin: Christianity in Twentieth Century Gaelic Short Stories . 141 Donald E. Meek Innovation and Tradition in the Drama of Críostóir Ó Floinn . 157 Eugene McKendry Seiftiúlacht Sheosaimh Mhic Grianna Mar Aistritheoir . 183 Seán Mac Corraidh An Gúm: The Early Years . 199 Gearóidín Uí Laighléis Possible Echoes from An tOileánach and Mo Bhealach Féin in Flann O’Brien’s The Hard Life . 217 Art J. Hughes Landscape in the Poetry of Sorley MacLean . 231 Pádraig Ó Fuaráin Spotlight on the Fiction of Angharad Tomos . 249 Sabine Heinz Breton Literature during the German Occupation (1940-1944): Reflections of Collaboration? . 271 Gwenno N. Piette Sven-Myer CELTIC LITERATURES IN THE TWENTIETH CENTURY INTRODUCTION The Centre for Irish and Celtic Studies at the University of Ulster hosted at Coleraine, between the 24th and 26th August 2000, a very successful and informative conference on Celtic Literatures in the Twentieth Century. The lectures and the discussions were of a high standard, and it was the intention of the organisers to edit and publish the proceedings as soon as possible thereafter. -

The Northern Dimension in Modern Scottish Literature

A Polar Projection: The Northern Dimension in Modern Scottish Literature by Michael Jon Anthony Stachura M.Litt. (English), The University of Stirling, 2009 M.A. (English), The University of Aberdeen, 2008 Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of English Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences © Michael Jon Anthony Stachura 2015 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Spring 2015 Approval Name: Michael Stachura Degree: Doctor of Philosophy (English) Title: A Polar Projection: The Northern Dimension in Modern Scottish Literature Examining Committee: Chair: Jeff Derksen Associate Professor Leith Davis Senior Supervisor Professor Susan Brook Supervisor Associate Professor Penny Fielding Supervisor Professor Department of English University of Edinburgh, Scotland Tina Adcock Internal Examiner Assistant Professor Department of History Scott Hames External Examiner Professor Department of English University of Stirling, Scotland Date Defended/Approved: April 8, 2015 ii Partial Copyright Licence iii Abstract Drawing on a transnational turn in recent Scottish literary criticism, this dissertation examines a transnational northern dimension in modern Scottish literature. Following a ‘No’ vote in an historic referendum on independence in 2014, the question of what Scotland and ‘Scottishness’ is in a post-referendum twenty-first century world is once again being debated and reimagined. Literature, as always in Scotland, will play a major role in this process. While the nation and national identity remain important subjects of critical focus and investigation, the writers examined within this dissertation offer ways of reorienting and reconsidering the conceptual, cultural, and creative boundaries of Scotland and Scottish literature, moving northwards into an awareness of as well as engagement with a Nordic and broader circumpolar world.