Conceptual Framework and Regional Context

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Timbul Site, Bali, and the Transformations Project: Material Remains and Considerations of Chronology and Typology

THE TIMBUL SITE, BALI, AND THE TRANSFORMATIONS PROJECT: MATERIAL REMAINS AND CONSIDERATIONS OF CHRONOLOGY AND TYPOLOGY Elisabeth A. Bacus Research Professor, University of Akron Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT The Timbul site, which a 2000 survey indicated had sig- nificant potential for the study of Bali's early states, was the focus of test excavations as part of the Transfor- mations in the Landscapes of South-Central Bali: An Ar- chaeological Investigation of Early Balinese States. This paper presents results of the analyses of the materials recovered from the 2004 excavations, their chronological information and an earthenware rim shape typology that is also tied to earthenware rim types from dated north coast sites. The excavated deposits, albeit limited, con- tribute further evidence of Bali's Early Metal period and rarely recovered settlement remains from possibly just prior to and during the early Classic period; these re- mains are discussed within the context of current archae- ological knowledge of these periods. INTRODUCTION South-central Bali (Figure 1), particularly the area be- tween the Pakerisan and Petanu rivers, is often considered to have been the center of the island's early states (Bernet Kempers 1991:114-115; Hobart et al. 1996:25). This area has yielded a high concentration of remains (e.g., bronze drums, carved stone sarcophagi) from the early complex societies of the mid/late-1st millennium BC to mid/late-1st millennium AD (Ardika 1987) and from the kingdoms of the Classic Period, particularly of the 11th to mid-14th cen- Figure 1 Location of the Timbul site tury AD. -

Assessment on Peatlands, Biodiversity and Climate Change: Main Report

Assessment on Peatlands, Biodiversity and Climate change Main Report Published By Global Environment Centre, Kuala Lumpur & Wetlands International, Wageningen First Published in Electronic Format in December 2007 This version first published in May 2008 Copyright © 2008 Global Environment Centre & Wetlands International Reproduction of material from the publication for educational and non-commercial purposes is authorized without prior permission from Global Environment Centre or Wetlands International, provided acknowledgement is provided. Reference Parish, F., Sirin, A., Charman, D., Joosten, H., Minayeva , T., Silvius, M. and Stringer, L. (Eds.) 2008. Assessment on Peatlands, Biodiversity and Climate Change: Main Report . Global Environment Centre, Kuala Lumpur and Wetlands International, Wageningen. Reviewer of Executive Summary Dicky Clymo Available from Global Environment Centre 2nd Floor Wisma Hing, 78 Jalan SS2/72, 47300 Petaling Jaya, Selangor, Malaysia. Tel: +603 7957 2007, Fax: +603 7957 7003. Web: www.gecnet.info ; www.peat-portal.net Email: [email protected] Wetlands International PO Box 471 AL, Wageningen 6700 The Netherlands Tel: +31 317 478861 Fax: +31 317 478850 Web: www.wetlands.org ; www.peatlands.ru ISBN 978-983-43751-0-2 Supported By United Nations Environment Programme/Global Environment Facility (UNEP/GEF) with assistance from the Asia Pacific Network for Global Change Research (APN) Design by Regina Cheah and Andrey Sirin Printed on Cyclus 100% Recycled Paper. Printing on recycled paper helps save our natural -

AID/CD-3296 Information, Solutions, Technical and Economic

FOR USE ONLY AGENCY FOR INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT AID WASHINGTON. D. C. 20523 I BIBLIOGRAPHIC INPUT SHEET A. PRIMARY 1.SUBJECT Agriculture CLASSI- FIAIN B. SECONDARY Insects and Pests 2. TITLE AND SUBTITLE Report of the Sahel Crop Pest Management Conference 3. AUTHOR(S) Smith, Ray F. and Schlegel, David E. 4. DOCUMENT DATE S. NUMBER OF PAGES 6. ARC NUMBER December 1974 8 6p. ARC - CI..31-.3..,) 7. REFERENCE ORGANIZATION NAME AND ADDRESS University of California Department of Entomological Sciences Berkeley, California 94720 8. SUPPLEMENTARY NOTES (Sponsoring Organization, Publiahera Availability) Conference conducted in Washington, D.C. December 11-12, 1974 9. ABSTRACT in the Sahel states In recent months, the increased demand for emergency assistance and long-term recovery has suggested certain conclusions which bear on the medium of the Sahel and development of the Sudano-Sahelian zone. The present capability This condition, states to manage common, annual crop pests is extremely limited. crop production. where it exists, will tend to neutralize attempts at increasing many are ready to The Sahel Governments are aware of the crop pest problem, and community are also seek a long-range solution to it. The members of the donor aware of the problem. The objectives of the Conference were: While any one concerned (1) To establish a technical understanding of the problem. been a comprehensive organization possessed valuable information, there had not compilation and exchange of such information. pest (2) To develop a technical consensus from the standpoint of professional solution to control management on the most appropriate approaches to the the problem. -

Building on Nature: Area-Based Conservation As a Key Tool for Delivering Sdgs

Area-based conservation as a key tool for delivering SDGs CITATION For the publication: Kettunen, M., Dudley, N., Gorricho, J., Hickey, V., Krueger, L., MacKinnon, K., Oglethorpe, J., Paxton, M., Robinson, J.G., and Sekhran, N. 2021. Building on Nature: Area-based conservation as a key tool for delivering SDGs. IEEP, IUCN WCPA, The Nature Conservancy, The World Bank, UNDP, Wildlife Conservation Society and WWF. For individual case studies: Case study authors. 2021. Case study name. In: Kettunen, M., Dudley, N., Gorricho, J., Hickey, V., Krueger, L., MacKinnon, K., Oglethorpe, J., Paxton, M., Robinson, J.G., and Sekhran, N. 2021. Building on Nature: Area-based conservation as a key tool for delivering SDGs. IEEP, IUCN WCPA, The Nature Conservancy, The World Bank, UNDP, Wildlife Conservation Society and WWF. CORRESPONDING AUTHORS Nigel Dudley ([email protected]) and Marianne Kettunen ([email protected]) PARTNERS Institute for European Environmental Policy (IEEP) IUCN World Commission on Protected Areas (WCPA) The Nature Conservancy (TNC) The World Bank Group UN Development Programme (UNDP) Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS) WWF DISCLAIMER The information and views set out in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect official opinions of the institutions involved. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This report and the work underpinning it has benefitted from the support of the following people: Sophia Burke (AmbioTEK CIC), Andrea Egan (UNDP), Marie Fischborn (PANORAMA), Barney Long (Re-Wild), Melanie McField (Healthy Reefs), Mark Mulligan (King’s College, London), Caroline Snow (proofreading), Sue Stolton (Equilibrium Research), Lauren Wenzel (NOAA), and from the many case study authors named individually throughout the publication. -

Durgā Mahiṣāsuramardinī in Likely Tantric Buddhist Context from The

https://pratujournal.org ISSN 2634-176X Durgā Mahiṣāsuramardinī in Likely Tantric Buddhist Context from the Northern Indian Subcontinent to 11th-Century Bali Durga Mahiṣāsuramardinī dalam konteks agama Buddha Tantrayana dari Subkontinen India Utara dan Bali pada abad ke-11 Ambra CALO Department of Archaeology and Natural History, The Australian National University [email protected] Translation by: Christa HARDJASAPUTRA, Alphawood Alumna, Postgraduate Diploma of Asian Art, SOAS University of London Edited by: Ben WREYFORD, Pratu Editorial Team Received 1 April 2019; Accepted 1 November 2019; Published 8 May 2020 Funding statement: The research for this study was funded by the Southeast Asian Art Academic Programme, Academic Support Fund (SAAAP #049), at SOAS University of London. The author declares no known conflict of interest. Abstract: This study examines the significance of the originally Hindu goddess Durgā Mahiṣāsuramardinī (Durgā slaying the buffalo demon) in Tantric Buddhist temple contexts of the 8th–11th century in Afghani- stan and northeastern India, and 11th-century Bali. Taking a cross-regional approach, it considers the genesis of Tantric Buddhism, its transmission to Indonesia, and its significance in Bali during the 10th–11th century. Drawing primarily on archaeological and iconographic evidence, it suggests that Durgā Mahiṣāsuramardinī is likely to have reached Bali as part of a late 10th–11th century phase of renewed transmission of Tantric Buddhism from the northeastern Indian subcontinent to Indonesia, following an initial late 7th–8th century phase. Keywords: Bali, Durgā, Heruka, Mahiṣāsuramardinī, maritime networks, Padang Lawas, Tantric Buddhism, Tantric Śaivism, Tapa Sardār, Uḍḍiyāna, Vajrayāna, Vikramaśīla, Warmadewa Abstrak: Penelitian ini melihat signifikansi dari dewi Hindu Durgā Mahiṣāsuramardinī (Durgā membunuh iblis kerbau) dalam konteks kuil Buddha Tantrayana pada abad ke-8 hingga ke-11 di Afghanistan dan timur laut India, serta abad ke-11 di Bali. -

Maps of Pleistocene Sea Levels in Southeast Asia: Shorelines, River Systems and Time Durations Harold K

^ Journal of Biogeography, 27, I 153-l I67 , Maps of Pleistocene sea levels in Southeast Asia: shorelines, river systems and time durations Harold K. Voris Field Museum of Natural History, Chicago, Illinois, USA Abstract Aim Glaciation and deglaciation and the accompanying lowering and rising of sealevels during the late Pleistoceneare known to have greatly affected land massconfigurations in SoutheastAsia. The objective of this report is to provide a seriesof mapsthat estimatethe areasof exposed land in the Indo-Australian region during periods of the Pleistocenewhen sealevels were below present day levels. Location The maps presentedhere cover tropical SoutheastAsia and Austral-Asia. The east-westcoverage extends 8000 km from Australia to Sri Lanka. The north-south coverage extends 5000 km from Taiwan to Australia. Methods Present-day bathymetric depth contours were used to estimate past shore lines and the locations of the major drowned river systemsof the Sunda and Sahul shelves. The timing of sea level changesassociated with glaciation over the past 250,000 years was taken from multiple sourcesthat, in some cases,account for tectonic uplift and sub- sidenceduring the period in question. Results This report provides a seriesof maps that estimate the areasof exposed land in the Indo-Australian region during periods of 17,000, 150,000 and 250,000 years before present. The ancient shorelinesare basedon present day depth contours of 10, 20, 30, 40,50,75, 100 and 120 m. On the maps depicting shorelinesat 75,100 and 120 m below present levels the major Pleistoceneriver systemsof the Sunda and Sahul shelves are depicted. Estimatesof the number of major sealevel fluctuation events and the duration of time that sealevels were at or below the illustrated level are provided. -

Physical Oceanography of the Southeast Asian Waters

UC San Diego Naga Report Title Physical Oceanography of the Southeast Asian waters Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/49n9x3t4 Author Wyrtki, Klaus Publication Date 1961 eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California NAGA REPORT Volume 2 Scientific Results of Marine Investigations of the South China Sea and the Gulf of Thailand 1959-1961 Sponsored by South Viet Nam, Thailand and the United States of America Physical Oceanography of the Southeast Asian Waters by KLAUS WYRTKI The University of California Scripps Institution of Oceanography La Jolla, California 1961 PREFACE In 1954, when I left Germany for a three year stay in Indonesia, I suddenly found myself in an area of seas and islands of particular interest to the oceanographer. Indonesia lies in the region which forms the connection between the Pacific and Indian Oceans, and in which the monsoons cause strong seasonal variations of climate and ocean circulation. The scientific publications dealing with this region show not so much a lack of observations as a lack of an adequate attempt to synthesize these results to give a comprehensive description of the region. Even Sverdrup et al. in “The Oceans” and Dietrich in “Allgemeine Meereskunde” treat this region superficially except in their discussion of the deep sea basins, whose peculiarities are striking. Therefore I soon decided to devote most of my time during my three years’ stay in Indonesia to the preparation of a general description of the oceanography of these waters. It quickly became apparent, that such an analysis could not be limited to Indonesian waters, but would have to cover the whole of the Southeast Asian Waters. -

What the UN Can Do to Assist Non-Self

What the UN Can Do To Assist Non-Self Governing Territories “Today, 17 Non-Self-Governing Territories across the globe remain under the purview of this Committee [Special Committee on Decolonization]. I call on the international community to address the issue of self-government and find innovative and practical ways to implement the decolonization process. In this endeavour, we shall be guided by the principles enshrined in the United Nations Charter and the relevant General Assembly resolutions.” —United Nations Secretary-General February 2015 04 CHART table of 06 MAP 08 HISTORICAL BACKGROUND contents 12 WHAT THE UNITED NATIONS CAN DO TO ASSIST NON-SELF-GOVERNING TERRITORIES 14 United Nations 21 United Nation Children’s Fund (UNICEF) 22 United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) 24 United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) 26 United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) 26 United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) 27 Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) 28 United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) 30 Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) 31 World Health Organization (WHO) 33 International Labour Organization (ILO) 35 Non-Self-Governing Territories (NSGTs) 36 Africa 37 Atlantic and Caribbean 46 Europe 47 Pacific listing administering land area territory populationI TERRITORIES TO WHICH THE DECLARATION ON THE GRANTING as nsgt power (Sq.km.)I OF INDEPENDENCE TO COLONIAL COUNTRIES AND PEOPLES CONTINUES TO APPLY (AS OF 2016) EUROPE Gibraltar Since 1946 United Kingdom -

REGIONAL OCEANS GOVERNANCE Making Regional Seas Programmes, Regional Fishery Bodies and Large Marine Ecosystem Mechanisms Work Better Together

www.unep.org United Nations Environment Programme P.O. Box 30552 Nairobi, 00100 Kenya Tel: (254 20) 7621234 Fax: (254 20) 7623927 E-mail: [email protected] web: www.unep.org REGIONAL OCEANS GOVERNANCE Making Regional Seas Programmes, Regional Fishery Bodies and Large Marine Ecosystem Mechanisms Work Better Together UNEP Regional Seas Reports and Studies No.197 CITATION: UNEP (2016): Regional Oceans Governance Making Regional Seas Programmes, Regional Fishery Bodies and Large Marine Ecosystem Mechanisms Work Better Together AUTHORS: Raphaël Billé, Lucien Chabason, Petra Drankier, Erik J. Molenaar, Julien Rochette SERIES: UNEP Regional Seas Reports and Studies No. 197 ISBN: 978-92-807-3579-6 JOB NUMBER: DEP/2003/NA COVER LAYOUT: Milcah Ndegwa, William Orlale (UNEP) COVER IMAGE: Shutterstock INFORMATION: UNEP Regional Seas Programme PO Box 30552 Nairobi, Kenya Tel.: +254 20 762 40 33 Fax: +254 20 762 46 18 www.unep.org/regionalseas Context of the paper The development of regional governance for the protection of the environment and its biodiversity is unquestionably a cornerstone of international environmental law and policy. With regard to marine and coastal issues, regional oceans governance has mainly been taking place through: (i) Regional Seas programmes, many of them supported or coordinated by the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP); (ii) regional fishery bodies (RFBs), some established under the framework of the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO); and (iii) Large Marine Ecosystem (LME) mechanisms, including projects supported by the Global Environment Facility (GEF). Although based on a similar geographical approach, there are concerns regarding their coordination and efficiency, and possibly overlaps in their aims. -

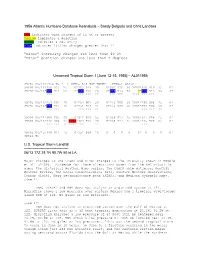

1956 Atlantic Hurricane Database Reanalysis – Sandy Delgado and Chris Landsea

1956 Atlantic Hurricane Database Reanalysis – Sandy Delgado and Chris Landsea Red indicates wind changes of 15 kt or greater Yellow indicates a deletion Green indicates a new entry Blue indicates lat/lon changes greater than 1º “Minor” intensity changes are less than 20 kt “Minor” position changes are less than 2 degrees Unnamed Tropical Storm 1 [June 12-15, 1956] – AL011956 39285 06/12/1956 M= 4 1 SNBR= 858 NOT NAMED XING=1 SSS=0 39290 06/12*220 915 25 0*225 913 30 0*231 912 30 1009*240 910 35 0* 39290 06/12*200 915 25 0*203 915 25 0*208 915 30 0*216 915 35 0* *** *** *** ** *** *** **** *** *** 39295 06/13*253 907 40 0*264 907 50 0*275 909 50 1004*290 908 45 0* 39295 06/13*230 915 40 0*251 913 45 0*275 909 50 1004*294 906 50 0* *** *** *** *** ** *** *** ** 39300 06/14*306 905 40 0*322 910 35 0*338 917 25 1006*347 928 25 0* 39300 06/14*310 906 35 1001*324 910 30 0*338 917 25 1006*345 928 25 0* *** *** ** **** *** ** *** 39305 06/15*349 933 25 0*352 938 20 0* 0 0 0 0* 0 0 0 0* 39310 TS U.S. Tropical Storm Landfall ------------------------------------- 06/13 17Z 29.1N 90.7W 50 kt LA Major changes to the track and minor changes to the intensity shown in McAdie et al. (2009). Evidence for these alterations comes from the NHC microfilm maps, the Historical Weather Maps series, the COADS ship database, Monthly Weather Review, the Local Climatological Data, Surface Weather Observations, Connor (1956), Navy reconnaissance book (ATSR), and Mexican synoptic maps. -

Biogeography of the Tropical Pacific!

Pacific Science (1992), vol. 46, no. 2: 276-293 © 1992.by University of Hawaii Press. All rights reserved Biogeography of the Tropical Pacific! D. R. STODDART2 ABSTRACT: Many previous biogeographic regionalizations of the islands and reefs of the tropical Pacific are unsatisfactory: the regions as defined are heterogeneous, localities with unlike biotas are grouped together, and those with similar characteristics are placed in separate categories. Often distinctions appear to be based on cultural or political rather than biogeographic consider~ ations. Criteria are defined for the establishment of biogeographic boundaries. Instead of the hierarchical schemes often utilized, it is proposed that the basis of biogeographic regionalization be typological. A distinction is made between the biogeographic characteristics of atolls and other reef islands, elevated limestone (makatea) islands, and high (often volcanic) islands. It is concluded that ifthe first two categories are filtered out, the treatment ofthe biogeography ofthe third group and hence the regionalization ofthe Pacific becomes relatively unproblematical. BIOGEOGRAPHERS HAVE BEEN CONCERNED with discuss the difficulties associated with existing the distribution of plants and animals in the schemes and suggest solutions for them. tropical Pacific for over a century (Sclater 1858, Wallace 1876,1882), and the differences between Pacific insular biotas and those of BIOGEOGRAPHIC REGIONAL SCHEMES East and Southeast Asia and Australia have long been recognized. Hedley (1899) was The problems may be illustrated by refer among the first to describe the profound ence to regional schemes proposed by the differences within the Pacific basin, especially zoologist Gressitt (1961, 1963) and the bota between the islands ofthe western Pacific and nist Thorne (1963). -

"Soft Power" in Southeast Asia

Order Code RL34310 China’s “Soft Power” in Southeast Asia January 4, 2008 Thomas Lum, Wayne M. Morrison, and Bruce Vaughn Specialists in Asian Affairs Foreign Affairs, Defense, and Trade Division China’s “Soft Power” in Southeast Asia Summary China’s growing use of “soft power” in Southeast Asia — non-military inducements including culture, diplomacy, foreign aid, trade, and investment — has presented new challenges to U.S. foreign policy. By downplaying many conflicting interests and working collaboratively with countries and regional organizations on such issues as territorial disputes and trade, Beijing has largely allayed Southeast Asian concerns that China poses a military or economic threat. China’s diplomatic engagement, compared to the perceived waning or limited attention by the United States, has earned the country greater respect in the region. Its rise as a major foreign aid provider and market for Southeast Asian goods has also enhanced its relations with Southeast Asian states. Many analysts contend that China’s growing influence may come at the expense of U.S. power and influence in the region. This report provides evidence and analysis of China’s soft power in Southeast Asia. It does not discuss the considerable U.S. military presence in the region. The report describes China’s evolving diplomacy and more active role in regional organizations such as the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN). Although China’s foreign aid to Southeast Asia, as in other regions, is difficult to quantify and includes a broader range of economic assistance than official development assistance (ODA) offered by major industrialized nations, it is believed to be relatively large.