China's Engagement in the Pacific Islands: Implications for the United

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

900 History, Geography, and Auxiliary Disciplines

900 900 History, geography, and auxiliary disciplines Class here social situations and conditions; general political history; military, diplomatic, political, economic, social, welfare aspects of specific wars Class interdisciplinary works on ancient world, on specific continents, countries, localities in 930–990. Class history and geographic treatment of a specific subject with the subject, plus notation 09 from Table 1, e.g., history and geographic treatment of natural sciences 509, of economic situations and conditions 330.9, of purely political situations and conditions 320.9, history of military science 355.009 See also 303.49 for future history (projected events other than travel) See Manual at 900 SUMMARY 900.1–.9 Standard subdivisions of history and geography 901–909 Standard subdivisions of history, collected accounts of events, world history 910 Geography and travel 920 Biography, genealogy, insignia 930 History of ancient world to ca. 499 940 History of Europe 950 History of Asia 960 History of Africa 970 History of North America 980 History of South America 990 History of Australasia, Pacific Ocean islands, Atlantic Ocean islands, Arctic islands, Antarctica, extraterrestrial worlds .1–.9 Standard subdivisions of history and geography 901 Philosophy and theory of history 902 Miscellany of history .2 Illustrations, models, miniatures Do not use for maps, plans, diagrams; class in 911 903 Dictionaries, encyclopedias, concordances of history 901 904 Dewey Decimal Classification 904 904 Collected accounts of events Including events of natural origin; events induced by human activity Class here adventure Class collections limited to a specific period, collections limited to a specific area or region but not limited by continent, country, locality in 909; class travel in 910; class collections limited to a specific continent, country, locality in 930–990. -

Traditions and Foreign Influences: Systems of Law in China and Japan

TRADITIONS AND FOREIGN INFLUENCES: SYSTEMS OF LAW IN CHINA AND JAPAN PERCY R. LUNEY, JR.* I INTRODUCTION By training, what I know about Chinese law comes from my study of the Japanese legal system. Japan imported several early Chinese legal codes in the seventh and eighth centuries and adapted this law to existing Japanese social and economic conditions. The Chinese Confucian philosophy and system of ethics was introduced to Japan in the fourteenth century. The Japanese and Chinese legal systems adopted Western-style legal codes to foster economic growth and international trade; and, more importantly, both have an underlying foundation of Confucian philosophy. As an outsider to the study of China, my views represent those of a comparativist commenting on his perceptions of foreign influences on the Chinese legal system. These perceptions are based on my readings about Chinese law, my professional study of Japanese law, and the presentation given by Professor Whitmore Gray ("The Soviet Background") at the 1987 Duke Conference on Chinese Civil Law. Legal reforms in China are generating much debate by Western legal scholars about the future of the Chinese legal system. After the fall of the Gang of Four, the new Chinese Government has sought to strengthen and to improve the stature of the legal system. The goal is a socialist legal system with Chinese characteristics.' The post-Mao leadership views the legal system as an essential element in the economic development process. 2 Chinese expectations are that a legal system can provide the societal stability necessary for economic Copyright © 1989 by Law and Contemporary Problems * Associate Professor, North Carolina Central University School of Law; Visiting Professor, Duke University School of Law. -

Taiwan's Fight for International Space

21 TAIWAN’S FIGHT FOR INTERNATIONAL SPACE Michael C. Burgoyne The Taiwan Strait separating Taiwan and the People’s Republic of Chi- na (PRC) has long been considered a geopolitical flashpoint. Both sides continue to plan and prepare for a kinetic attempt by the PRC to coerce Taiwan into unification. However, the gains in the conflict between these two entities have largely been made in non-kinetic ways: fights over dip- lomatic recognition and attendance in international bodies, among others. The battleground in which this non-kinetic fight has taken place has come to be labeled “international space,” where Taiwan is striving for mean- ingful participation in the international community—broadly defined and evaluated in this chapter as diplomatic relations and participation in inter- governmental organizations (IGO)—and the PRC is trying to isolate the island from these interactions. Having its roots in the Chinese civil war that culminated in the 1940s, this fight is crucially important for both sides. The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) sees Taiwan as a matter of legitimacy. The Party portrays itself as a staunch defender of sovereignty and territorial integrity to its citizens, yet Taiwan remains outside its control, which it feels could dele- gitimize it in the eyes of the populace. Constricting Taiwan’s international space is a way to leave Taiwan with no other choice than eventual unifica- tion. Taiwan sees itself as a separate country in a practical sense, with a strong, advanced economy and many advantages; yet it is only recognized as a country by 14 nations, and lacks representation in many IGOs. -

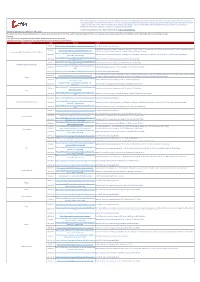

Papua New Guinea

PAPUA NEW GUINEA EMERGENCY PREPAREDNESS OPERATIONAL LOGISTICS CONTINGENCY PLAN PART 2 –EXISTING RESPONSE CAPACITY & OVERVIEW OF LOGISTICS SITUATION GLOBAL LOGISTICS CLUSTER – WFP FEBRUARY – MARCH 2011 1 | P a g e A. Summary A. SUMMARY 2 B. EXISTING RESPONSE CAPACITIES 4 C. LOGISTICS ACTORS 6 A. THE LOGISTICS COORDINATION GROUP 6 B. PAPUA NEW GUINEAN ACTORS 6 AT NATIONAL LEVEL 6 AT PROVINCIAL LEVEL 9 C. INTERNATIONAL COORDINATION BODIES 10 DMT 10 THE INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT COUNCIL 10 D. OVERVIEW OF LOGISTICS INFRASTRUCTURE, SERVICES & STOCKS 11 A. LOGISTICS INFRASTRUCTURES OF PNG 11 PORTS 11 AIRPORTS 14 ROADS 15 WATERWAYS 17 STORAGE 18 MILLING CAPACITIES 19 B. LOGISTICS SERVICES OF PNG 20 GENERAL CONSIDERATIONS 20 FUEL SUPPLY 20 TRANSPORTERS 21 HEAVY HANDLING AND POWER EQUIPMENT 21 POWER SUPPLY 21 TELECOMS 22 LOCAL SUPPLIES MARKETS 22 C. CUSTOMS CLEARANCE 23 IMPORT CLEARANCE PROCEDURES 23 TAX EXEMPTION PROCESS 24 THE IMPORTING PROCESS FOR EXEMPTIONS 25 D. REGULATORY DEPARTMENTS 26 CASA 26 DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH 26 NATIONAL INFORMATION AND COMMUNICATIONS TECHNOLOGY AUTHORITY (NICTA) 27 2 | P a g e MARITIME AUTHORITIES 28 1. NATIONAL MARITIME SAFETY AUTHORITY 28 2. TECHNICAL DEPARTMENTS DEPENDING FROM THE NATIONAL PORT CORPORATION LTD 30 E. PNG GLOBAL LOGISTICS CONCEPT OF OPERATIONS 34 A. CHALLENGES AND SOLUTIONS PROPOSED 34 MAJOR PROBLEMS/BOTTLENECKS IDENTIFIED: 34 SOLUTIONS PROPOSED 34 B. EXISTING OPERATIONAL CORRIDORS IN PNG 35 MAIN ENTRY POINTS: 35 SECONDARY ENTRY POINTS: 35 EXISTING CORRIDORS: 36 LOGISTICS HUBS: 39 C. STORAGE: 41 CURRENT SITUATION: 41 PROPOSED LONG TERM SOLUTION 41 DURING EMERGENCIES 41 D. DELIVERIES: 41 3 | P a g e B. Existing response capacities Here under is an updated list of the main response capacities currently present in the country. -

Diversity Visa Program, DV 2019-2021: Number of Entries During Each Online Registration Period by Region and Country of Chargeability

Diversity Visa Program, DV 2019-2021: Number of Entries During Each Online Registration Period by Region and Country of Chargeability The totals below DO NOT represent the number of diversity visas issued nor the number of selected entrants Countries marked with a "0" indicate that there were no entrants from that country or area. Countries marked with "N/A" were typically not eligible for that program year. FY 2019 FY 2020 FY 2021 Region Foreign State of Chargeabiliy Entrants Derivatives Total Entrants Derivatives Total Entrants Derivatives Total Africa Algeria 227,019 123,716 350,735 252,684 140,422 393,106 221,212 129,004 350,216 Africa Angola 17,707 25,543 43,250 14,866 20,037 34,903 14,676 18,086 32,762 Africa Benin 128,911 27,579 156,490 150,386 26,627 177,013 92,847 13,149 105,996 Africa Botswana 518 462 980 552 406 958 237 177 414 Africa Burkina Faso 37,065 7,374 44,439 30,102 5,877 35,979 6,318 2,591 8,909 Africa Burundi 20,680 16,295 36,975 22,049 19,168 41,217 12,287 11,023 23,310 Africa Cabo Verde 1,377 1,272 2,649 894 778 1,672 420 312 732 Africa Cameroon 310,373 147,979 458,352 310,802 165,676 476,478 150,970 93,151 244,121 Africa Central African Republic 1,359 893 2,252 1,242 636 1,878 906 424 1,330 Africa Chad 5,003 1,978 6,981 8,940 3,159 12,099 7,177 2,220 9,397 Africa Comoros 296 224 520 293 128 421 264 111 375 Africa Congo-Brazzaville 21,793 15,175 36,968 25,592 19,430 45,022 21,958 16,659 38,617 Africa Congo-Kinshasa 617,573 385,505 1,003,078 924,918 415,166 1,340,084 593,917 153,856 747,773 Africa Cote d'Ivoire 160,790 -

The Timbul Site, Bali, and the Transformations Project: Material Remains and Considerations of Chronology and Typology

THE TIMBUL SITE, BALI, AND THE TRANSFORMATIONS PROJECT: MATERIAL REMAINS AND CONSIDERATIONS OF CHRONOLOGY AND TYPOLOGY Elisabeth A. Bacus Research Professor, University of Akron Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT The Timbul site, which a 2000 survey indicated had sig- nificant potential for the study of Bali's early states, was the focus of test excavations as part of the Transfor- mations in the Landscapes of South-Central Bali: An Ar- chaeological Investigation of Early Balinese States. This paper presents results of the analyses of the materials recovered from the 2004 excavations, their chronological information and an earthenware rim shape typology that is also tied to earthenware rim types from dated north coast sites. The excavated deposits, albeit limited, con- tribute further evidence of Bali's Early Metal period and rarely recovered settlement remains from possibly just prior to and during the early Classic period; these re- mains are discussed within the context of current archae- ological knowledge of these periods. INTRODUCTION South-central Bali (Figure 1), particularly the area be- tween the Pakerisan and Petanu rivers, is often considered to have been the center of the island's early states (Bernet Kempers 1991:114-115; Hobart et al. 1996:25). This area has yielded a high concentration of remains (e.g., bronze drums, carved stone sarcophagi) from the early complex societies of the mid/late-1st millennium BC to mid/late-1st millennium AD (Ardika 1987) and from the kingdoms of the Classic Period, particularly of the 11th to mid-14th cen- Figure 1 Location of the Timbul site tury AD. -

Mapping the Information Environment in the Pacific Island Countries: Disruptors, Deficits, and Decisions

December 2019 Mapping the Information Environment in the Pacific Island Countries: Disruptors, Deficits, and Decisions Lauren Dickey, Erica Downs, Andrew Taffer, and Heidi Holz with Drew Thompson, S. Bilal Hyder, Ryan Loomis, and Anthony Miller Maps and graphics created by Sue N. Mercer, Sharay Bennett, and Michele Deisbeck Approved for Public Release: distribution unlimited. IRM-2019-U-019755-Final Abstract This report provides a general map of the information environment of the Pacific Island Countries (PICs). The focus of the report is on the information environment—that is, the aggregate of individuals, organizations, and systems that shape public opinion through the dissemination of news and information—in the PICs. In this report, we provide a current understanding of how these countries and their respective populaces consume information. We map the general characteristics of the information environment in the region, highlighting trends that make the dissemination and consumption of information in the PICs particularly dynamic. We identify three factors that contribute to the dynamism of the regional information environment: disruptors, deficits, and domestic decisions. Collectively, these factors also create new opportunities for foreign actors to influence or shape the domestic information space in the PICs. This report concludes with recommendations for traditional partners and the PICs to support the positive evolution of the information environment. This document contains the best opinion of CNA at the time of issue. It does not necessarily represent the opinion of the sponsor or client. Distribution Approved for public release: distribution unlimited. 12/10/2019 Cooperative Agreement/Grant Award Number: SGECPD18CA0027. This project has been supported by funding from the U.S. -

Chinese Foreign Aid and the Unga Voting Patterns of the Recipients

CHINESE FOREIGN AID AND THE UNGA VOTING PATTERNS OF THE RECIPIENTS by ABULAITI ABUDULA Submitted to the Graduate School of Social Sciences in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Sabancı University December 2018 ABULAITI ABUDULA 2018 © All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT CHINESE FOREIGN AID AND THE UNGA VOTING PATTERNS OF THE RECIPIENTS ABULAITI ABUDULA M.A. THESIS in POLITICAL SCIENCE, DECEMBER 2018 Thesis Supervisor: Asst. Prof. Kerem Yıldırım Keywords: Chinese aid, Voting patterns, UN General Assembly Using panel data for 120 countries over the period 2000-2014, this paper imperially analyzes the impact of Chinese aid on the voting patterns of countries in the UN General Assembly. I utilize the disaggregated Chinese aid data for the fact that distinct forms of aid flows may differ in their capability to induce recipients to vote for China’s favor. The results suggest that only Chinese grants are the aid category by which recipients have been induced to vote in line with China. iv ÖZET ÇİN DIŞ YARDIMLARI VE ALICININ BM GENEL KURULU OY VERME BİÇİMLERİ ABULAITI ABUDULA SİYASET BİLİMİ YÜKSEK LİSANS TEZİ, ARALIK 2018 Tez Danışmanı: Dr. Öğr. Üyesi Kerem Yıldırım Anahtar Kelimeler: Çin yardımı, Oy verme biçimleri, BM Genel Kurulu 2000-2014 döneminde 120 ülke için panel verilerini kullanan bu tez, Çin yardımının BM Genel Kurulunda ülkelerin oy kullanma düzenleri üzerindeki etkisini ampirik olarak incelemektedir. Farklı yardım kategorileri, alıcıları Çin’in lehine oy kullanmaya teşvik etmede farklılık yaratabileceği için ayrıştırılmış Çin yardım verileri kullanılmıştır. Sonuçlar, yalnızca Çin hibelerinin, alıcıların Çin lehine oy kullanmaya teşvik edildiği bir yardım kategorisi olduğunu göstermektedir. -

Guide Pédagogique Projects Doing Things with Words

guide pédagogique projects doing things with words Coordination pédagogique Juliette Ban-Larrosa et Jean-Louis Picot Agrégés de l’université Inspecteurs d’Académie Inspecteurs Pédagogiques Régionaux Auteurs Sylvain Basty Professeur certifi é Lycée André Boulloche, Livry-Gargan (93) Benjamin Baudin Professeur agrégé Lycée André Boulloche, Livry-Gargan (93) Francis Laboue Professeur certifi é Lycée Robert de Mortain, Mortain (50) Claudine Lennevi Professeur agrégé Lycée Marie Curie, Vire (14) Pour la langue orale Jeremy Reyburn Inspecteur d’Académie Inspecteur Pédagogique Régional Conception maquette : Marc & Yvette Couverture : Agence Mercure Mise en page : IGS « Le photocopillage, c’est l’usage abusif et collectif de la photocopie sans autorisation des auteurs et des éditeurs. Largement répandu dans les établissements d’enseignement, le photocopillage menace l’avenir du livre, car il met en danger son équilibre économique. Il prive les auteurs d’une juste rémunération. En dehors de l’usage privé du copiste, toute reproduction totale ou partielle de cet ouvrage est interdite. » « La loi du 11 mars 1957 n’autorisant, au terme des alinéas 2 et 3 de l’article 41, d’une part, que les copies ou reproductions strictement réservées à l’usage privé du copiste et non destinées à une utilisation collective » et, d’autre part, que les analyses et les courtes citations dans un but d’exemple et d’illustration, « toute représentation ou reproduction intégrale, ou partielle, faite sans le consentement de l’auteur ou de ses ayants droit ou ayants cause, est illicite. » (alinéa 1er de l’article 40) - « Cette représentation ou reproduction, par quelque procédé que ce soit, constituerait donc une contrefaçon sanctionnée par les articles 425 et suivants du Code pénal. -

Cook Islands Pops Project Country Plan

SPREP PROE South Pacific Regional Programme régional Environment Programme océanien de l'environnement PO Box 240, APIA, Samoa. Tel.: (685) 21 929, Fax: (685) 20 231 E-mail: [email protected] Website: http://www.sprep.org.ws/ Please use [email protected] if you encounter any problems with [email protected] File: AP 6/3/2 Vanuatu POPs Project Country Plan (Prepared by SPREP, January 2003) 1. Introduction The Australian Agency for International Development (AusAID) several years ago identified the mismanagement of hazardous chemicals in the Pacific Island Countries as a serious environmental concern, and hence the Persistent Organic Pollutants in Pacific Island Countries (POPs in PICs) project was developed as an AusAID funded initiative, to be carried out by SPREP. POPs are a group of twelve particularly hazardous chemicals that have been singled out by the recent Stockholm Convention for urgent action to eliminate them from the world. They include polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), which are mainly found in transformers, and several pesticides that are very persistent and toxic to the environment. Phase I of the project involved predominantly an assessment of stockpiles of waste and obsolete chemicals and identification of contaminated sites, for 13 Pacific Island Countries. Other Phase I activities included education and awareness programmes in each country and a review of relevant legislation. Vanuatu was a participant in Phase I of this work. A comprehensive report of this Phase I work was prepared and circulated, and significant quantities of hazardous wastes were identified in the countries visited, including estimated figures of 130 tonnes of PCB liquids and 60 tonnes of pesticides (although only about 3 tonnes of POPs pesticides). -

List of Certain Foreign Institutions Classified As Official for Purposes of Reporting on the Treasury International Capital (TIC) Forms

NOT FOR PUBLICATION DEPARTMENT OF THE TREASURY JANUARY 2001 Revised Aug. 2002, May 2004, May 2005, May/July 2006, June 2007 List of Certain Foreign Institutions classified as Official for Purposes of Reporting on the Treasury International Capital (TIC) Forms The attached list of foreign institutions, which conform to the definition of foreign official institutions on the Treasury International Capital (TIC) Forms, supersedes all previous lists. The definition of foreign official institutions is: "FOREIGN OFFICIAL INSTITUTIONS (FOI) include the following: 1. Treasuries, including ministries of finance, or corresponding departments of national governments; central banks, including all departments thereof; stabilization funds, including official exchange control offices or other government exchange authorities; and diplomatic and consular establishments and other departments and agencies of national governments. 2. International and regional organizations. 3. Banks, corporations, or other agencies (including development banks and other institutions that are majority-owned by central governments) that are fiscal agents of national governments and perform activities similar to those of a treasury, central bank, stabilization fund, or exchange control authority." Although the attached list includes the major foreign official institutions which have come to the attention of the Federal Reserve Banks and the Department of the Treasury, it does not purport to be exhaustive. Whenever a question arises whether or not an institution should, in accordance with the instructions on the TIC forms, be classified as official, the Federal Reserve Bank with which you file reports should be consulted. It should be noted that the list does not in every case include all alternative names applying to the same institution. -

Shipping Operations Updated 6 April 2021

Please note, although we endeavour to provide you with the most up to date information derived from various third parties and sources, we cannot be held accountable for any inaccuracies or changes to this information. Inclusion of company information in this matrix does not imply any business relationship between the supplier and WFP / Logistics Cluster, and is used solely as a determinant of services, and capacities. Logistics Cluster /WFP maintain complete impartiality and are not in a position to endorse, comment on any company's suitability as a reputable service provider. If you have any updates to share, please email them to: [email protected] Shipping Operations Updated 6 April 2021 This bulletin is compiled to give all stakeholders an overview of the current impact of COVID-19 on Pacific shipping activities. It draws on sources from government, commercial and humanitarian sectors. The bulletin will now be circulated monthly. Overview • UN Bodies call for seafarers and aviation workers to be given priority access to vaccines • Massive congestion in European and Asian ports anticipated due to resolved Suez Canal blockage State / Territory Date Source Details 26-Mar-21 https://info.swireshipping.com/shipping-schedules/oceania See link for Swire Shipping schedule. Kaimana Hila arrives on 4 March. Maunawili arrives on 11 March. Daniel K. Inouye arrives on 18 March. Manukai arrives 25 March. Maunawili departs 25-Feb-21 https://www.matson.com/fss/reports/guam_s.pdf Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands on 9 March. Daniel K. Inouye departs on 14 March. Manukai departs 21 March. https://www.pdl123.co.nz/common/downloads/images/sch 24-Feb-21 Neptune Pacific has vessels arriving on 7 & 21 March, 10 & 21 April, 5 & 24 May, 4 & 18 June, 7 & 18 July, 20 & 31 August and 14 September.