1 the Drivers Affecting the Intermodal Development ______49

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Britain's Transition from Rail to Road-Based Food Distribution, 1919-1975 Thomas James Spain MA

‘Food Miles’: Britain’s Transition from Rail to Road-based Food Distribution, 1919-1975 Thomas James Spain MA Doctor of Philosophy University of York Railway Studies September 2016 Abstract Britain’s railways were essential for the development of the British economy throughout the nineteenth century; however, by 1919 their seemingly unassailable position as goods carriers was about to be eroded by the lorry. The railway strike of September 1919 had presented traders with an opportunity to observe the capabilities of road haulage, but there is no study which focuses on the process of modal shift in goods distribution from the trader’s perspective. This thesis therefore marks an important departure from the existing literature by placing goods transport into its working context. The importance of food as an everyday essential commodity adds a further dimension to the status of goods transport within Britain’s supply chain, particularly when the fragility of food products means that minimising the impact of distance, time and spoilage before consumption is vital in ensuring effective and practical logistical solutions. These are considered in a series of four case studies on specific food commodities and retail distribution, which also hypothesise that the modal shift from rail to road reflected the changing character of transport demand between 1919 and 1975. Consequently, this thesis explores the notion that the centre of governance over the supply chain transferred between food producers, manufacturers, government and chain retailer, thereby driving changes in transport technology and practice. This thesis uses archival material to provide a qualitative study into the food industry’s relationship with transport where the case studies incorporate supply chain analyses to permit an exploration of how changes in structure might have influenced the modal shift from rail to road distribution. -

CATALOGUE Visit Our Website Antiquetoys.Com.Au to View All Items, Download a PDF Catalogue Suitable for Printing, and See Previews of Forthcoming Auction Items

First Monday Toy Auction TRAINS, PLANES & AUTOMOBILES Monday 4th June 2018 at 6:00pm Join us in our Auction Rooms at Unit 4, 30-32 Livingstone Street, Lawson, NSW 2783 Or watch & bid online at invaluable.com Highlights include • Superb collection of Australian HO • More HO/OO from Hornby, Lima and others • Great selection of O-gauge including ACE, Bassett-Lowke, Hornby, Lionel, Marx, Mettoy, and several Australian brands, also live steam locomotives • Railway novelty items including a whiskey bottle train set • Dinky & Corgi diecast cars • Matchbox 1-75’s and King Size • 1:18 & 1:24 scale cars Featured item: Lot 76 Bassett-Lowke O-gauge LMS 2-6-4 Stanier Tank Locomotive • Tinplate vehicles and other tin toys For full details visit antiquetoys.com.au VIEWING Items can be viewed at our Auction Rooms on the Saturday before the auction from 10:00am to 4:00pm, and on the day of the auction from 3:00pm. CATALOGUE Visit our website antiquetoys.com.au to view all items, download a PDF catalogue suitable for printing, and see previews of forthcoming auction items. We can also supply printed catalogues on request for $5.00 each. BIDDING Absentee bids may be left on our website, by phone, by email, or in person during viewings or at our Blackheath shop. Live bidding is available at the venue or online at Invaluable Auctions – visit invaluable.com to register as a bidder. Telephone bidding is also available by prior arrangement. BUYER’S PREMIUM A 13.5% buyer’s premium applies to all successful bids (includes GST). -

Dorrigo Railway Museum

DORRIGO RAILWAY MUSEUM - EXHIBIT LIST No.39 Steam Locomotives (44): Compiled 171412013 by KJ:KJ All Locomotives are 4'STz" gauge PAGE 1 Number Wheel Builder and Year Of Manufacture Price Weiqht Previous Operator Arranqement 1 "JUNO" 0-4-0ST Andrew Barclay, Sons & Co. Ltd. 1923 $1300 34 tons Commonwealth Steel Co. Ltd. 2 "Bristol Bomber" 0-6-05T Avonside Engine Co. - Bristol (U.K.) 1922 $2500 40 tons J. & A. Brown 3 0-6-0sr Kitson & Co. - Leeds (U K ) 1878 $1300 35 tons J. & A. Brown 3 0-6-07 Andrew Barclay, Sons & Co. Ltd. 1911 $10000 41tons Blue Circle Southern Cement 4 0-4-07 H. K. Porter, Pittsburgh (U.S.A.) 1915 Donated 50 tons Commonwealth Steel Co. Ltd. 5 0-6-07 Andrew Barclay, Sons & Co. Ltd. 1916 $50,000 50 tons Blue Circle Southern Cement 'CORBY" O-4-OST Peckett & Sons Ltd. - Bristol (U K ) 1943 $500 24 tons Tubemakers of Australia Ltd. "MARIAN'' O-4-OST Andrew Barclay, Sons & Co. Ltd. 1948 $1775 36 tons John Lysaght (Aust.) Limited "BADGER' 0-6-05T Australian lron & Steel (Pt Kembla) 1943 $3400 67 tons Australian lron and Steel 14 (S.M.R.) 0-8-27 Avonside Engine Co. - Bristol (U.K.) 1909 Donated 60 tons S.M.R./Peko-Wallsend 20 (ROD 1984) 2-8-O North British Locomotive Co. - Glasgow 1918 $2500 121 tons J. & A. Brown 24 (ROD 2003) 2-8-0 Great Central Railway - Gorton U.K. 1918 $6000 121 tons J. & A. Brown 27 (S.M.R. No 2) 0-4-0ST Avonside Engine Co - Bristol (U.K.) 1900 $1300 27 tons S.M.R./J. -

Transportation As a Medium for Spatial Interaction: a Case Study Of

t' TRANSPORTATION AS A MEDIUM FOR SPATIAL INTERACTION: A CASE STUDY OF KENYA’S RAILWAY NETWORK. ^ BY STEPHEN AMBROSE LULALIRE/ONGARO DEPARTMENT OF GEOGRAS’Hy ' UNIVERSITY OF NAIROBI A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE UNIVERSITY OF NAIROBI IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN ECONOMIC GEOGRAPHY. 1995 QUOTES "It is not uncommon thing for a line to open-up a country, but this line literally created a country". Sir Charles Elliot, 1903. (Kenya Railways Museum Annex) "The degree of civilization enjoyed by a nation may be measured by the character of its transportation facilities." Byers, M.L. 1908. DEDICATION I dedicate this thesis to the memory of my Jate grandfather, Topi Mutokaa iii DECLARATION This thesis is my original work and has, to the best of my knowledge, not been submitted for a degree in any other university. (Master of Arts Candidate) r / This thesis has been submitted for examination with our approval as University of Nairobi supervisors. iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I take this opportunity to acknowledge the help and guidance that was extended to me during the course of conducting this study. It was instrumental in the conduct and final production of this work. I am heavily indebted to Professor Reuben B. Ogendo, a father-figure who has been my university supervisor since July 1988. He encouraged me to pursue a postgraduate course and has been a source of valuable guidance. I gained a lot from his probing questions and incisive advice. I am thankful for the guidance that I received from Mr. -

You Can Search This Index in Adobe Reader by Clicking Ctrl+Shift+F Or Clicking the Arrow Beside the Find Button

INDEX TO THE NZ MODEL RAILWAY JOURNAL , FEBRUARY 1986 TO NOW SEARCHING : You can search this index in Adobe Reader by clicking Ctrl+Shift+F or clicking the arrow beside the Find button. Click Open Full Reader Search and type a word or phrase to search for into the box headed: What word or phrase would you like to search for? then click Search . You can search for any part word, word or phrase. Hint: Take care with spelling and if in doubt use part words, ie, search for "kero" rather than "kerosine", which can be spelt two ways. Hint: Most topics begin with a category heading, such as Locomotivery, Tools, etc, and it may often be useful to search by one of these categories. Your search will return a list of all the matches to the text you typed. You can click on any of these to see the full entry and what else is in the same Journal . (Note: The matches listed usually include text from the beginning of the next item. The end of the searched item is marked by two hash ## signs. Errors and other problems: Please report typos or other errors, or any problems using the index to Peter Ross, [email protected] KEY TO CATEGORIES : Added detail: Self-explanatory. Bits & bytes: Use of digital (ie, computer) technology, including DCC and onboard sound. Bridges: Bridges, culverts, viaducts, etc. road or rail. Car & wagon: Carriages, wagons and other rail-mounted equipment, eg, mobile cranes. Electrics: Wiring layouts, making, applying or controlling electronic accessories. For DCC see Bits & Bytes. -

London & North Eastern Railway Carriage & Wagon Drawings Lists

London & North Eastern Railway Carriage & Wagon Drawings Gorton, York, Cowlairs, Hull, Stratford, LNER Engineers and Carriage Diagrams Lists Gorton Carriage & Wagon Drawings List Used on Drawing Earliest Date Roll No. Prefix Suffix Office Code Title of drawing Drawing Additional information No. Found No. LD&ECR Diagrams of Wagon Stock 104 6 DR C No date CFB; “109” in red [departmental] 104 7 DR C 1/9/1896 LD&ECR Covered Goods Wagon 7DR.C* Wagon wb 9’-0”; “113” in red; tinted Wagon wb 9’-0”; “106” in red; “Obsolete”; labelled successively LD&ECR, GCR and 104 10 DR C No date LD&ECR Goods & Coal Wagon 10DR.C* LNER; actually numbered 10DR-C authenticating policy adopted here Truck; wb 6'-10½"+6'-10½"; Brown 013B 13 DR C 29/4/1897 LD&ECR 20T Machine Truck 13DR.C* Marshalls & Co Ltd Britannia Works, Birmingham 14 24 DR C No date LD&ECR Cattle Wagon 24DR.C* Wagon; wb 11'-0" 104 26 DR C No date LD&ECR Tool Van for Accident Train 26DR.C* Van (body only); “133” in red; tinted; TV\ - Van wb 15’-0”; “134” in red; lettered “Loco 104 27 DR C No date LD&ECR Tool Van for Accident Train 27DR.C* Tool Van No 551”; tinted Wagon wb 9’-0”; “107” in red; Charles 104 28 DR C 8/2/1898 P LD&ECR 10T Open Goods Wagon 28DR.C* Roberts & Co Ltd, Horbury Junction, near Wakefield 8/2/1898 stamp Gorton Carriage & Wagon Drawings List Used on Drawing Earliest Date Roll No. -

Express Toy Auction

Hugo Marsh Neil Thomas Plant (Director) Shuttleworth (Director) (Director) Express Toy Auction 27th February 2018 at 10:00 Viewing: 26th February 2018 10:00-16:00 Otherwise by Appointment Bob Leggett Dominic Foster Saleroom One, Toys, Trains & Toys 81 Greenham Business Park, Figures NEWBURY RG19 6HW Telephone: 01635 580595 Fax: 0871 714 6905 Email: [email protected] www.specialauctionservices.com Graham Bilbe Robin Trains O’Connor Toys Buyers Premium: 17.5% plus Value Added Tax making a total of 21% of the Hammer Price Internet Buyers Premium: 20.5% plus Value Added Tax making a total of 24.6% of the Hammer Price Diecast Models 6. Atlas Editions Dinky, A boxed 12. Atlas Editions Dinky, A boxed group of ten models including vintage group of ten models including vintage 1. Post-War Play-Worn Diecast, private Lincoln, Willys, Ford, Chevrolet, private, commercial and competition, Post-War Play-Worn Diecast, Mostly Packard, Dodge and Studebaker Morris, Jaguar, Triumph, Austin- unboxed private, commercial and vehicles, (532 (2), 80B, 555, 552 (2), Healey, Aston-Martin and Bedford Order of Auction competition vehicles including 24P, 191, 540 and 24 O), G-E, Boxes vehicles, (197(2), 157(2), 105, 111, examples by Spot-On, Dinky and G-E (10) £50-80 546, 506,104 and 481) G-E, Boxes F-E Solido amongst others, such as a Spot- (10) £50-80 On, Volkswagen, Dinky, Ford GT and 7. Atlas Editions Dinky, A boxed Corgi Major, Ecurie Ecosse Racing Car group of ten models including vintage 13. Atlas Editions Dinky, A boxed Transporter, together with two boxed private Citroen vehicles, (24N (3), 24C, group of ten models including vintage Corgi and Dinky Silver Jubilee double 500, 522, 530, 539 (2) and 011500), commercial Trojan, Ford, Citroen, 1-150 Diecast Models decker buses, P-G, Boxes F (Qty) G-E, Boxes G-E, (10) Peugeot and Renault vehicles, (453 £50-80 £50-80 (2), 25A, 1200K, 25CG, 561, 25B (2) 151-164 Toys and 563 (2) ) G-E, Boxes G-E (10) 165-189 Plastic Kits 2. -

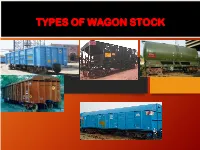

Types of Wagon Stock Introduction

TYPES OF WAGON STOCK INTRODUCTION ❖ Rolling stock used exclusively for transport of goods is termed as freight stock ❖ In order to transport goods, the wagons are required ❖ The earliest types of wagons were in the form of four sided wooden boxes, either open or closed at top ❖ Earlier wagons were four wheeler type ❖ Gradually, the design of the wagon has gone under considerable changes and modifications ❖ Indian railways transports all types of goods such as building materials, coal, sugarcane, animals, chemicals, cloths, food-grains, oils, petrol, explosives, automobiles, medicines, perishable goods, milk, finished products of high and low values, paper etc. ❖ In order to meet the requirements of each type of goods, the wagons of different designs are employed CLASSIFICATION OF WAGON Freight Stock are broadly classified either according to their under gear or according to utility According to: 1. Under gear 2. Utility ACCORDING TO UNDER GEAR 1. Four wheeler wagon • Conventional Wagons • Modified Wagons • Tank Wagons At present only Brake van is in service 2. Bogie wagons • Diamond frame bogie • Cast steel Bogie • UIC fabricated bogie • CASNUB Bogie At present only CASNUB bogie wagon is in service ACCORDING TO UTILITY ▪ Open wagons ▪ Covered wagons ▪ Flat wagons ▪ Well wagons ▪ Hopper wagons ▪ Container wagons ▪ Tank wagons ▪ Brake vans TRANSPORTATION CODES USED FOR WAGONS • HS : High Speed • LA : Low flat car with • HA : Higher Axle Load standard buffer height • LW : Light weight • LB : Low flat car with • HL : Higher Pay Load low buffer -

Chapter 1. a Holocaust in Trains (Introduction)

– Chapter 1 – INTRODUCTION A Hidden Holocaust in Trains “Move over. Make room for the others!” We squeezed and crushed in as if we were animals. A man with only one leg cried out in agony and his horrifi ed wife pleaded with us not to press against him. We traveled in the dark crush for a long, long time. No air. No food. People urinating continuously in the latrines. Then the shriek. Over the moans and helpless little cries, there rose a piercing scream I shall never forget. From a woman on the fl oor beneath the small, barred window came the horrifying scream. She held her head in both her hands and then we who were close by saw the words scratched in tiny letters: “last transport went to Auschwitz.”1 When we were marched out to the cattle trains, you have a cattle train in the Washington museum, I never really knew what the dimensions were, nobody could tell me, it’s about three quarters the size of a regular tour bus … there were about 170 people packed into this cattle car. At fi rst some people wanted to pre- vent the panic, to tell people, “look people, organize, stand up, there is no room for everyone to sit” … but it didn’t work, people were in a panic, the young and strong were standing at the windows, blocking whatever air there was.2 Even today freight cars give me bad vibes. It is customary to call them cattle cars, as if the proper way to transport animals is by terrorizing and overcrowd- ing them. -

Auction Database 0206 IN

Toy Train Auction Lot Descriptions STOUT AUCTIONS January 19, 2013 801 Prewar Lionel O gauge 2613 Pullman missing a hand rail, 2614 observation, and 2615 baggage, passenger cars, C6. 802 Postwar HAG Switzerland electric locomotive with two passenger cars, C6. 803 Prewar Lionel O gauge 253 electric boxcab loco with 613 Pullman coach, 614 observation, and 615 baggage, trains look nicer C6 area. 804 Postwar JEP O gauge RO E.501 electric locomotive with two SBB CFF passenger cars, one baggage/combine and one 2nd and 3rd class passenger coach. Trains look nicer C6-7. Loco has nice castings, repainted pantographs or red primer showing through chips. 805 Prewar Lionel O gauge 812 gondolas with mixed trim, coupler, and shades of green, variations. One missing brake wheel and one missing coupler latch box. Trains otherwise look C6 area. 806 Prewar Lionel O gauge 248 boxcab electric locos, one is in orange with casting fatigued wheels and missing diecast headlight. Green loco has good original wheels but missing a coupler. Green looks C5-6, orange looks C6. 807 Postwar Paya freight/goods gondola car, P.H. 1354 / 20000K. Two cars, both have workers dog house, both tarp/cover support bars (one broken but included), one has tarp marked Juguetes P.N. 1101. Trains have some very light casting fatigue to some wheels, some distortion to diecast end pieces, one end piece has a very small chip to corner. 808 Prewar Lionel O gauge 511 flatcars in tougher to find aluminum with latch couplers variation, C6. Cars have left brake wheels on one and right brake wheels on other. -

Glorious Trains Part Two

Hugo Marsh Neil Shuttleworth Thomas Forrester Director Director Director Glorious Trains Part Two Tuesday 29th June 2021 at 10.00 Special Auction Services Contact the below specialists for further information: Plenty Close Off Hambridge Road NEWBURY RG14 5RL Telephone: 01635 580595 Email: [email protected] www.specialauctionservices.com Dominic Foster Graham Bilbe Bob Leggett Toys Trains Toys,Trains & Figures Due to the nature of the items in this auction, buyers must satisfy themselves concerning their authenticity prior to bidding and returns will not be accepted, subject to our Terms and Conditions. Additional images are available on request. Buyers Premium with SAS & SAS LIVE: 20% plus Value Added Tax making a total of 24% of the Hammer Price the-saleroom.com Premium: 25% plus Value Added Tax making a total of 30% of the Hammer Price 1. A Hornby 0 Gauge No 3E 6-volt 6. A converted Hornby 0 Gauge No 10. An assortment of Hornby 0 AC ‘Flying Scotsman’ Locomotive only, an O Locomotive and Tender, both in Great Gauge Clockwork Mechanisms, including early example with external brush-caps to Western lined green, the early loco without an early No 2 motor fitted for ‘Control’ the right side, black smokebox and plain cylinders as no 2251, originally clockwork operation (from 4-4-0 or 4-4-4T), lacks gold numbers to cab-sides, G-VG, light and now fitted with an original Hornby control rods otherwise G-VG, with three playwear, very slight damage to front right 20v electric mechanism with replacement No 1 motor units (nickelled sides) -

Dual Gauge? CM1500 Kit £749.00 Combine Narrow Gauge with Gauge 3 Using Our Range of G64/G45 Dual Gauge Trackwork

Including Now Stocking Now Stocking ‘O’ Gauge Latest News and Offers ‘O’ Gauge Second Hand Sales Prices include VAT. Commission Sale items (Prefix SECOM) are sold on behalf of the owner and are open to ’Best Offer’. Please visit our website for up to date details on new and secondhand items. If you would prefer to read our Newsletter in Electronic Format, please see www.grsuk.com where you can either download a pdf version, or opt in to joining our mailing list and have the latest sent to you as soon as it is published Station Studio, 6 Summerleys Road, Princes Risborough, Bucks, HP27 9DT Tel: 01844 345158 Email: [email protected] Web: www.grsuk.com LIVE STEAM UPDATE New Live Steam Locomotives GRS ‘K1 Garratt’ gas fired, 45/32mm in lined black, lined Grey, one only in plain satin black - £3895.00 Man. £4195.00 R/C GRS ‘GVT’ 0-4-0T gas fired, 45mm in black or Green - £1350.00 Man. £1600.00 R/C Accucraft ‘Dolgoch’ 0-4-0WT, 32 or 45mm, Atlas Green, TR Green, or Red - £1550.00 Man. £1850.00 R/C Accucraft ‘Sabrina’ 0-4-0ST, 32 or 45mm, Green, Black, or Maroon - £1050.00 Man. £1350.00 R/C Accucraft ‘Talgarth’ 0-4-0T, 32 or 45mm, Green, Black, or Maroon - £1050.00 Man. £1350.00 R/C Roundhouse ‘Leek & Manifold’ 2-6-4T gas fired, 32 or 45mm gauge, R/C, Crimson Lake - £2020.00 Roundhouse ‘Bulldog’ 0-4-0 Diesel, R/C, Ins. Wheels, 45/32mm, Darj. Blue, or Light Brunswick Green with Red frames £634.00 Second Hand Live Steam Locomotives Pearse "Countess" 32/45mm R/C and whistle - £1995.00 Aristocraft ‘Rogers’ 0-4-0 tender engine, R/C, With metal carrying