Sexual Scripts in the Slasher Sub-Genre

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Agnese Discusses Guns, Progress by Stephen M

VOL. 116. NO. 4 www.uiwlogos.org October 2015 Agnese discusses guns, progress By Stephen M. Sanchez LOGOS NEWS EDITOR The University of the Incarnate Word community will be polled to get its views on the state’s new law allowing concealed guns on campus but UIW will likely opt out, the president said. Dr. Louis J. Agnese Jr., who’s been president 30 years, shared this with those who attended his annual “State of the University” address on Oct. 6 at CHRISTUS Heritage Hall. Agnese also gave a mostly upbeat report on the university’s growth in his “Looking Ahead to 2020” PowerPoint presentation, pointing out how UIW has grown from 1,300 students and a budget of $8 mil- lion when he first became president in 1985 to its 11,000 students globally and budget in the hundreds of millions today. He’s seen a small college morph into the fourth-largest private school in the state and the largest Catholic institution in the state. UIW currently has 10 campuses in San Antonio, one in Corpus Christi, and another in Killeen. The university also contracts with 144 sister schools overseas in its Study Abroad program. More than 80 majors are offered including bachelor’s, master’s and doctoral degrees. UIW also has professional schools in pharmacy, optometry and physical therapy with a School of Osteopathic Medicine set to open in fall 2017 at Brooks City Base. UIW students also receive more than $150 million annually in financial aid. - Cont. on page 2 Stephen M. Sanchez/ LOGOS NEWS EDITOR -Agnese discusses progress. -

SKYDANCE MEDIA CASTS NATALIA REYES, DIEGO BONETA, and GABRIEL LUNA to STAR in UPCOMING TERMINATOR PROJECT After a Global Ta

SKYDANCE MEDIA CASTS NATALIA REYES, DIEGO BONETA, AND GABRIEL LUNA TO STAR IN UPCOMING TERMINATOR PROJECT After a global talent search, Skydance Media announced today Natalia Reyes ("Lady, La Vendedora de Rosas"), Diego Boneta (“Scream Queens,” Rock of Ages), and Gabriel Luna (“Marvel’s Agents of S.H.I.E.L.D.”) will join MaCkenzie Davis as the new stars of the latest Terminator project directed by Tim Miller (Deadpool) and produced by James Cameron and David Ellison. Specific details on the characters are being kept under wraps As previously announced, Arnold Schwarzenegger and Linda Hamilton are set to star in the film which is scheduled for release the Friday before Thanksgiving on November 22, 2019. The movie will be a direct sequel to Cameron's Terminator 2: Judgment Day, with Schwarzenegger and Hamilton anchoring the story while passing the baton to a new generation of characters. The film will be distributed domestically by Paramount Pictures and internationally by 20th Century Fox. Natalia Reyes, is a Colombian actress best known for her starring role in Sony's hit Latin America series "Lady, La Vendedora de Rosas" and as one of the stars of Peter Webber’s Netflix original film Pickpockets. In 2017, she shot Sumergible produced by Ecuadorian director Sebastián Cordero and was part of Sticks and Stones a film by Martin SkovbJerg in Denmark. She Just finished shooting Running with the Devil, an upcoming American thriller starring Nicolas Cage. Reyes is a graduate of the Lee Strasberg Theatre and Film Institute (New York City). Mexican-born actor Diego Boneta, made his feature debut in the musical Rock of Ages. -

Why Emma Roberts Is My Spirit Animal

Dating Tip #77: Google the person. Thursday, October 15, 2015 12A The Valdosta Daily Times The video !! art of brain tra surgery FROM JOE Medical Degrees: 0 Malpractice Suits: Too many to count XX he patient is readied. My #vdtxtra assistants are ready. My Thands are washed. It’s time to start on an appendectomy. Just as I make my first incision, I get the horrific realization I forgot some- thing. Maybe it’s the fact the patient just let out a bone-chilling scream that could be heard by everyone on the helipad six stories above us. My lead assistant looks at me, not really im- pressed with my minor mistake. “You know, that wasn’t really the proper procedure,” he tells me, as calm as ever. The chief surgeon, trying to make par 3 on the 15th in one stroke, had his phone go off just as he made the shot. When he stormed into my vicinity, I thought he was going to wrap his 5-iron around my throat. “I am outraged at your unbelievable incompetence!” he roared in my direc- tion. Gee, thanks. I found out later his shot wound up beaning someone Gerald Ford-style. My job was now to take care of this guy. JOE By the way, I should point out that I’m really just playing a game — “Life and Death,” a game by Software Toolworks which came out in 1988. The first game focused on the lower body — the appendix, the stomach, etc. Its sequel, “Life and Death II,” focused on the brain. -

Video Deo Arrow Video Arrow Row Arrow Video Rrow Video Arrow Arrow Video Arrow Video Arrow Video Arrow Video Arrow Video Arrow V

VIDEO VIDEO Film historians David Bordwell and Kristin Thompson from the yellow jackets of the plethora of detective ARROW state VIDEOthat “a genre is easier to recognise than to novels that began to saturate the Italian market in the BLOOD AND BLACK GLOVES define”define”.. Rarely has this seemed more relevant than late 1920s, among them translations of the works of when referring to the giallo – a sensual, stylish and authors as diverse as Arthur Conan Doyle, Raymond Michael Mackenzie on the Giallo luridly violent body of Italian murder-mystery films Chandler and Agatha Christie. The giallo film is ARROW which, like the AmericanVIDEO films noir which preceded something altogether different and more narrowly them by a few decades, responded to a unique defined, emerging in the early 1960s and enjoying set of sociocultural upheavals and were therefore a brief spell of immense popularity in the early-to- influenced as much by the period in which they were mid 1970s. The conventions of these films have been VIDEO ARROWproduced as by generic conventions.VIDEO The Italians well-established elsewhere and are iconic enough have a specific term to describe this phenomenon: that even those without an intimate knowledge of filone , meaning ‘vein’ or ‘streamlet’. These faddish, the genre can recognise them: the black gloves, hat often highly derivative genres each tended to enjoy and trench coat that disguise the killer’s identity and VIDEO ARROWa brief spell of immense popularity andVIDEO prolificacy gender; the modern urban locales which provide a beforeore fading into obscurity as quickly as they backbackdrop to the carnage that unfolds; the ‘whodunit’ firstt appeared, their creative potential (and their investigative narratives with their high body counts audience’sience’sARROW appetite for more of the same) exhausted. -

City Approves Soccer Field

ThePublished News since 1890 every Monday and Thursday Reporterfor the County of Columbus and her people. Monday, December 7, 2015 Unaffiliated Volume 125, Number 46 Whiteville, North Carolina candidate to 75 Cents challenge Russ By NICOLE CARTRETTE Inside News Editor Lavern Coleman, 61, of the Byrdville com- 3-A munity, said he plans to run as an unaffili- ated candidate in the November 2016 general • City worker certified election. as playground Coleman is a supervisor in the paper divi- inspector. sion at International Paper in Riegelwood where he has worked for 41 years. He must obtain signatures from 4 percent of registered 4-A voters in Columbus County Commissioner • Unusual wreck District 4 to get his name on the ballot. Thursday kills Unaffiliated candidates break-in suspect. may petition with the sig- natures of 4 percent of registered voters in the 5-A district by the last Friday • Virginia Lane is no in June to get on the bal- ‘ordinary’ woman. lot, according to the N.C. State Board of Elections and N.C. General Statutes DIDYOB? 163-122 a (3). Coleman said Friday he Russ Did you observe ... did not know how many names he needed to obtain and was originally told by Members of Peace Staff photo by FULLER ROYAL county election employees Baptist Church that he would have to run Candy over-loaded mother lode as a write-in candidate. He moving along This youngster grabs as much candy as he can during the Whiteville Christmas Parade after the was contacted the next day Madison Street riders on the Simply Dance float threw hundreds of pieces of candy all at once. -

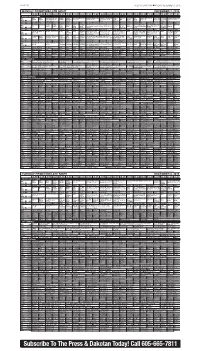

Subscribe to the Press & Dakotan Today!

PAGE 8B PRESS & DAKOTAN n FRIDAY, DECEMBER 4, 2015 MONDAY PRIMETIME/LATE NIGHT DECEMBER 7, 2015 3:00 3:30 4:00 4:30 5:00 5:30 6:00 6:30 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 12:00 12:30 1:00 1:30 BROADCAST STATIONS Odd Odd Wild Kratts: A Crea- Martha Nightly PBS NewsHour (N) (In Antiques Roadshow Antiques Roadshow Choice Tossed The Red BBC Charlie Rose (N) (In Tavis Smi- The Mind Antiques Roadshow PBS Squad Squad ture Christmas (In Speaks Business Stereo) Å “Pittsburgh” Å “Junk in the Trunk Cuts: Out Green World Stereo) Å ley (N) Å of a Chef “Junk in the Trunk KUSD ^ 8 ^ Stereo) (EI) Å Report 4” Å Meats in Show News “Prune” 4” Å KTIV $ 4 $ Meredith Vieira Ellen DeGeneres News 4 News News 4 Ent The Voice (N) (In Stereo Live) Å Telenov Telenov News 4 Tonight Show Seth Meyers Daly Extra (N) Paid Hot Bench Hot Bench Judge Judge KDLT Nightly KDLT The Big The Voice “Live Semi-Final Performances” The Telenove- Telenove- KDLT The Tonight Show Late Night With Seth Last Call KDLT (Off Air) NBC Å Å Judy Å Judy Å News News News Bang remaining nine artists perform. (N) (In Stereo la “Pilot” la “Evil News Å Starring Jimmy Fallon Meyers (N) (In Ste- With Car- News Å KDLT % 5 % (N) Å (N) Å Theory Live) Å (N) Twin” (N) (N) Å reo) Å son Daly KCAU ) 6 ) Dr. -

Linnea Quigley's

Linnea Quigley’s PARANORMAL TRUTH New TV Series 12 x 30min Linnea Quigley’s PARANORMAL TRUTH 1 DISCLAIMER: Red Rock Entertainment Ltd is not authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA). The content of this promotion is not authorised under the Financial Services and Markets Act 2000 (FSMA). Reliance on the promotion for the purpose of engaging in any investment activity may expose an individual to a significant risk of losing all of the investment. UK residents wishing to participate in this promotion must fall into the category of sophisticated investor or high net worth individual as outlined by the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA). CONTENTS 4 Synopsis 5 Narrator (Host) | Paranormal Investigator 6 | 17 Episodes 18 Producers 19 Executive Producers 20 Writers, Director, Producers 22 Equity SYNOPSIS Paranormal events and purported first century? Or is it just a way for desert in 1971. The truly intriguing phenomena that are described in filmmakers to make money from the combination of an abduction event popular culture, folk, and other audience? that would result in an apparent non-scientific bodies of knowledge, UFO crash near Edwards Air Force whose existence within these We follow that with the truths Base in California. The incident took contexts are described as beyond behind a man who was known as place only eighteen months before normal experience or scientific the wickedest man in the world one of the most active years for explanation. Linnea Quigley, Queen and the template for Ian Flemings’s UFO and occupant sightings in the of the scream queens, guides you character, Ernst Stavro Blofeld in United States in 1973. -

LIONS GATE ENTERTAINMENT CORP. (Exact Name of Registrant As Specified in Its Charter)

Table of Contents UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 Form 10-K (Mark One) ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the fiscal year ended March 31, 2012 or TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the transition period from to Commission File No.: 1-14880 LIONS GATE ENTERTAINMENT CORP. (Exact name of registrant as specified in its charter) British Columbia, Canada N/A (State or Other Jurisdiction of (I.R.S. Employer Incorporation or Organization) Identification No.) 1055 West Hastings Street, Suite 2200 2700 Colorado Avenue, Suite 200 Vancouver, British Columbia V6E 2E9 Santa Monica, California 90404 (877) 848-3866 (310) 449-9200 (Address of Principal Executive Offices, Zip Code) Registrant’s telephone number, including area code: (877) 848-3866 Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act: Title of Each Class Name of Each Exchange on Which Registered Common Shares, without par value New York Stock Exchange Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(g) of the Act: None ___________________________________________________________ Indicate by check mark if the registrant is a well-known seasoned issuer, as defined in Rule 405 of the Securities Act. Yes No Indicate by check mark if the registrant is not required to file reports pursuant to Section 13 or Section 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934. Yes No Indicate by check mark whether the registrant (1) has filed all reports required to be filed by Section 13 or Section 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 during the preceding 12 months (or for such shorter period that the registrant was required to file such reports), and (2) has been subject to such filing requirements for the past 90 days. -

Thanks Atlanta Mcdreamy Grey’S Anatomy and Scandal, One for Voting Us As Atlanta’S Best Art Supply Store of the Most Fun Shows on TV

TV Station Control TRASH IS THE NEW ART BY BENJAMIN CARR Lady GaGa in American RITER-PRODUCERS OF THE Horror Story: Hotel bygone era whose names were synonymous with quality television: WNorman Lear (All in the Family), James L. Brooks (The Simpsons, Mary Tyler Moore), Stephen Bochco (L.A. Law, NYPD Blue), David E. Kelley (Picket Fences, Ally McBeal), David Simon (Homicide, The Wire) and David Chase (The Sopranos) have been replaced with the likes of Shonda Rhimes and Ryan Murphy. With today’s producers, what we get in terms of quality feels more like grand trash than great art. But the most addictive, reliable TV has always been that. Rhimes powerhouse hits are long in the tooth but still watchable even though they killed Thanks Atlanta McDreamy Grey’s Anatomy and Scandal, one For Voting Us As Atlanta’s Best Art Supply Store of the most fun shows on TV. Murphy has been for 4 Consecutive Years! churning out lots of mostly hit shows since Nip/Tuck. His shows are generally oversexed, SERVING ATLANTA FROM TWO CONVENIENT LOCATIONS musical, nutty affairs that concentrate on style and shock first, logic and plot almost never. BUCKHEAD PONCE CITY MARKET Shows like Nip/Tuck and Glee are usually good held even the weakest of plots together with sheer 3330 Piedmont Rd, Suite 18 650 North Ave NE, Suite 102 for a season or two, then they spectacularly verve. In her place, Murphy has given us Lady Atlanta, GA 30305 Atlanta, GA 30308 implode or just go completely off the rails, but Gaga, who in a couple uncomfortable episodes 404.237.6331 404.682.6999 never stop. -

Revue REVUE CINEMA

REVUE CINEMA DECEMBER VOLUME 8 ISSUE 12 PARASITE THE LIGHTHOUSE JOJO RABBIT DOWNTON ABBEY DOCTOR SLEEP NEW CHRISTMAS CLASSICS, THE RETURN OF STUDIO GHIBLI ON SCREEN Revue & THE TOP MUSIC DOCS OF THE YEAR Join us for this final month of the decade as we screen the cinema. We’ve designated both restrooms as gender- Cinema some fun classics and new releases. We’ve got November neutral, removed stationed seats from the auditorium, so holdovers The Lighthouse (one of the top films of the that those using mobility devices can feel as though they Holiday year!) and Downton Abbey, Shining sequel Doctor Sleep, are in the row of seats, and not the aisle. We have installed Last Christmas, Jojo Rabbit and Parasite (probably the closed captioning devices and wireless headsets to help best film of the year?). those who are vision and hearing impaired. There is still Gift Pack! This year was one of the top in terms of music documentary a lot of work to do, but every single person should feel as releases, so we’re happy to present several of them: Linda though they are part of the Revue experience. Ronstadt: The Sound of My Voice, Marianne & Leonard: We’ve also undertaken some much-needed leasehold Words of Love, Amazing Grace, We Were Brothers: improvements. Our building is an old one, and beyond Robbie Robertson & The Band, Echo in the Canyon, and some minor roof repairs, one of our maintenance projects Miles Davis: Birth of the Cool. On-screen throughout the was the restoration of the sound box behind the building. -

August 20, 2015 Welcome to 225.342.FILM, the Official Hotline Of

August 20, 2015 Welcome to 225.342.FILM, the official hotline of Louisiana Entertainment. Here’s what’s currently happening in August. PRE-PRODUCTION JACK REACHER: NEVER GO BACK Feature film Jack Reacher: Never Go Back starring tom Cruise will shoot October 19th through February 1st in New Orleans. Please send resumes to [email protected] GAMBIT 20th Century Fox feature film Gambit will shoot November 9th in New Orleans. Please send resumes to [email protected] ONE MISSISSIPPI Independent feature film One Mississippi will shoot August 31st through September 4th in New Orleans. Please send resumes to [email protected] LBJ Independent feature film LBJ starring Woody Harrelson will shoot September 21st through November 3rd in New Orleans. Please send resumes to [email protected] WORK HORSES Independent feature film Work Horses is scheduled to shoot September 18th for 6 weeks in Shreveport. Please send resumes to [email protected] FILMING ROOTS The Mini Series Roots starring Laurence Fishburne is filming August 20th in New Orleans. Please send resumes to [email protected] HUNTER KILLER Independent feature film Hunter/Killer starring Gerard Butler, Billy Bob Thornton and Willem Dafoe is filming August 3rd through September in New Orleans. Please send resumes to [email protected] SCREAM QUEENS Fox Television series Scream Queens starring Emma Roberts, Jamie Lee Curtis and Abigail Breslin is filming June 19th through November in New Orleans. Please send resumes to [email protected] NCIS: NEW ORLEANS SEASON 2 CBS television series NCIS: New Orleans Season 2 is filming July 7th-April 25th in New Orleans. -

1 September 2021 Vol. 50 No.12

1 SEPTEMBER 2021 VOL. 50 NO.12 2 3 ZERO MILE AND SOBATL PRESENT TWO NIGHTS SEPT 10 & 11 OF AMAZING LOUISIANA MUSIC & CUISINE! REBIRTH WE HAVE like SEPTEMBER 2021 BRASS Volume 50 • Issue 12 BAND ON THE GO? share 8 follow CREATIVELOAFING.COM COVER STORY: SILVER 404.688.5623 SCREAM SPOOK SHOW Shane Morton and Madeline PUBLISHER • Ben Eason [email protected] Brumby keep scaring people MANAGING EDITOR • Tony Paris BY KEVIN C. MADIGAN [email protected] EVENTS EDITOR • Jessica Goodson SERATONES THINGS COPY EDITOR • JJ Krehbiel 5 GRAPHIC DESIGNERS • Katy Barrett-Alley, AJ Fiegler TO DO CONTRIBUTING WRITERS Cliff Bostock, Ema Carr, Curt Holman, 18 Hal Horowitz, Lauren Keating, Kevin C. Madigan, TODAY... Tony Paris, Joshua Robinson GRAZING CONTRIBUTING ARTISTS Tray Butler Barbecue on my mind CONTRIBUTING PHOTOGRAPHERS BY CLIFF BOSTOCK Cliff Bostock INTERNS • Carolina Avila, Hailey Conway, Grace Karas CL RADIO & PODCASTS • Jill Melancon OPERATIONS MANAGER • Kartrina Thomas [email protected] 20 SOBATL.COM | 404.875.1522 SALES EXECUTIVES 1578 PIEDMONT AVE NE, ATLANTA, GA 30324 Andrew Cylar, Carrie Karas MUSIC FEATURE ...AND National Advertising Sales John Daly and ‘The Low VMG Advertising 1-888-278-9866 or 1-212-475-2529 Level Hum’ SEPTEMBER 17 EVERYDAY SR. VP OF SALES OPERATIONS • Joe Larkin SUBMISSIONS BY KEVIN C. MADIGAN Please direct any and all editorial submissions, LITTLE inquiries, story ideas, photography and art queries to the managing editor. STRANGER FOUNDERS Deborah and Elton Eason PIP THE PANSY 24 DAMN SKIPPY ATL UNTRAPPED $12 ADV/ $17 DAY OF | 9PM The rebirth of Rome Fortune SEPTEMBER 18 BY JOSHUA ROBINSON ANGIE 29 APARO AN EVENING W/ ANGIE SCREEN TIME APARO, SEATED SHOW! Out on Film and more $30 ADV/ $35 DAY OF | 8PM BY CURT HOLMAN Editor’s note: In last month’s print CHECK OUT edition we inadvertently left off the ABOUT THE COVER: byline for ATL Untrapped.