Complete Issue

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Who's Who in Basque Music Today

Who’s Who in Basque music today AKATZ.- Ska and reggae folk group Ganbara. recorded in 2000 at the circles. In 1998 the band DJ AXULAR.- Gipuzkoa- Epelde), accomplished big band from Bizkaia with Accompanies performers Azkoitia slaughterhouse, began spreading power pop born Axular Arizmendi accordionist associated a decade of Jamaican like Benito Lertxundi, includes six of their own fever throughout Euskadi adapts the txalaparta to invariably with local inspiration. Amaia Zubiría and Kepa songs performed live with its gifted musicians, techno music. In his second processions, and Angel Junkera, in live between 1998 and 2000. solid imaginative guitar and most recent CD he also Larrañaga, old-school ALBOKA.-Folk group that performances and on playing and elegant adds voices from the bertsolari and singer who has taken its music beyond record. In 2003 he recorded melodies. Mutriku children's choir so brilliantly combines our borders, participating a CD called "Melodías de into the mix, with traditional sensibilities and in festivals across Europe. piel." CAMPING GAZ & DIGI contributions by Mikel humor, are up to their ears Instruments include RANDOM.- Comprised of Laboa. in a beautiful, solid and alboka, accordion and the ANJE DUHALDE.- Singer- Javi Pez and Txarly Brown enriching project. Their txisu. songwriter who composes from Catalonia, the two DOCTOR DESEO.- Pop rock fresh style sets them apart. in Euskara. Former member joined forces in 1995, and band from Bilbao. They are believable, simple, ALEX UBAGO.-Donostia- of late 70s folk-rock group, have since played on and Ringleader Francis Díez authentic and, most born pop singer and Errobi, and of Akelarre. -

Cae El Comando De ETA Más Peligroso

Esports Páginas 10 y 11 SASTRE,CERCA ESPAÑA, OLEGUER DEL AMARILLO IMPARABLE VA AL AJAX Ya es cuarto en la general.Hoy La selección de El Barça accede se disputa la etapa reina de los basket también a traspasarlo al Alpes,donde se juega el Tour. gana a Argentina club holandés. Cae el comando de ETA más peligroso En una operación coordinada por el juez Garzón, la Guardia Civil detiene a 9 El primer diario que no se vende miembros del‘comandoVizcaya’, «el más activo y dinámico» de la banda: se le 24 atentados en menos de un año, uno de ellos con un muerto. 6 Dimecres 23 atribuyen JULIOL DEL 2008. ANY IX. NÚMERO 1979 Cues, llargues esperes i incidents a les oficines de l’atur de l’àrea metropolitana La falta de personal i l’augment d’aturats està des- bordant el servei a Badalona, Terrassa o Cornellà. 4 El piso de las policías asesinadas en Bellvitge parecía «una sala de torturas» Los investigadores aseguran que todas las pruebas incriminan sólo al único acusado del doble crimen. 3 Una ‘escultura filtrabicicletes’ barra el pas a las bicis al parc de Collserola L’han instal·lada enmig d’un camí exclusiu de via- nants per evitar que es facin malbé els esglaons.2 PUBLICIDAD ! O L ÉSTE ERA EL JEFE. Se llama Arkaitz Goikoetxea, tiene 28 años y comenzó en la kale borroka. En 2001 perdió dos dedos de una mano al lanzar un cóctel molotov contra la Policía vasca. En la foto, ayer tras ser detenido en un piso de Bilbao. -

The Case of Eta

Cátedra de Economía del Terrorismo UNIVERSIDAD COMPLUTENSE DE MADRID Facultad de Ciencias Económicas y Empresariales DISMANTLING TERRORIST ’S ECONOMICS : THE CASE OF ETA MIKEL BUESA* and THOMAS BAUMERT** *Professor at the Universidad Complutense of Madrid. **Professor at the Catholic University of Valencia Documento de Trabajo, nº 11 – Enero, 2012 ABSTRACT This article aims to analyze the sources of terrorist financing for the case of the Basque terrorist organization ETA. It takes into account the network of entities that, under the leadership and oversight of ETA, have developed the political, economic, cultural, support and propaganda agenda of their terrorist project. The study focuses in particular on the periods 1993-2002 and 2003-2010, in order to observe the changes in the financing of terrorism after the outlawing of Batasuna , ETA's political wing. The results show the significant role of public subsidies in finance the terrorist network. It also proves that the outlawing of Batasuna caused a major change in that funding, especially due to the difficulty that since 2002, the ETA related organizations had to confront to obtain subsidies from the Basque Government and other public authorities. Keywords: Financing of terrorism. ETA. Basque Country. Spain. DESARMANDO LA ECONOMÍA DEL TERRORISMO: EL CASO DE ETA RESUMEN Este artículo tiene por objeto el análisis de las fuentes de financiación del terrorismo a partir del caso de la organización terrorista vasca ETA. Para ello se tiene en cuenta la red de entidades que, bajo el liderazgo y la supervisión de ETA, desarrollan las actividades políticas, económicas, culturales, de propaganda y asistenciales en las que se materializa el proyecto terrorista. -

Anuario Del Seminario De Filología Vasca «Julio De Urquijo» International Journal of Basque Linguistics and Philology

ANUARIO DEL SEMINARIO DE FILOLOGÍA VASCA «Julio DE URQUIJo» International Journal of Basque Linguistics and Philology LIII (1-2) 2019 [2021] ASJU, 2019, 53 (1-2), 1-38 https://doi.org/10.1387/asju.22410 ISSN 0582-6152 – eISSN 2444-2992 Luis Michelena (Koldo Mitxelena) y la creación del Seminario de Filología Vasca «Julio de Urquijo» 1 (1947-1956)1 Luis Michelena (Koldo Mitxelena) and the founding of the «Julio de Urquijo» Basque Philology Seminar (1947-1956) Antón Ugarte Muñoz* ABSTRACT: We are presenting below the history of the founding of the «Julio de Urquijo» Basque Philology Seminar, created by the Provincial Council of Gipuzkoa in 1953, whose tech- nical adviser and unofficial director was the eminent linguist Luis Michelena. KEYWORDS: Luis Michelena, Koldo Mitxelena, Basque studies, intellectual history. RESUMEN: Presentamos a continuación la historia de la fundación del Seminario de Filología Vasca «Julio de Urquijo», creado por la Diputación Provincial de Gipuzkoa en 1953, cuyo asesor téc- nico y director oficioso fue el eminente lingüista Luis Michelena. PALABRAS CLAVE: Luis Michelena, Koldo Mitxelena, estudios vascos, historia intelectual. 1 Una versión de este artículo fue presentada en las jornadas celebradas en Vitoria-Gasteiz (2019- 12-13) por el grupo Monumenta Linguae Vasconum de la UPV/EHU que dirigen los profesores Blanca Urgell y Joseba A. Lakarra, a quienes agradezco su invitación. El significado de las abreviaturas emplea- das se encuentra al final del texto. * Correspondencia a / Corresponding author: Antón Ugarte Muñoz. Etxague Jenerala, 14 (20003 Donostia/San Sebastián) – ugarte. [email protected] – https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0102-4472 Cómo citar / How to cite: Ugarte Muñoz, Antón (2021). -

Euskadi-Bulletinen: Swedish Solidarity with the Basque Independence Movement During the 1970'S Joakim Lilljegren

BOGA: Basque Studies Consortium Journal Volume 4 | Issue 1 Article 3 October 2016 Euskadi-bulletinen: Swedish Solidarity with the Basque Independence Movement During the 1970's Joakim Lilljegren Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.boisestate.edu/boga Part of the Basque Studies Commons Recommended Citation Lilljegren, Joakim (2016) "Euskadi-bulletinen: Swedish Solidarity with the Basque Independence Movement During the 1970's," BOGA: Basque Studies Consortium Journal: Vol. 4 : Iss. 1 , Article 3. https://doi.org/10.18122/B2MH6N Available at: http://scholarworks.boisestate.edu/boga/vol4/iss1/3 Euskadi-bulletinen: Swedish solidarity with the Basque independence movement during the 1970's Joakim Lilljegren, M.A. In the Swedish national library catalogue Libris, there are some 200 items in the Basque language. Many of them are multilingual and also have text for example in Spanish or French. Only one of them has the rare language combination Swedish and Basque: Euskadi-bulletinen, which was published in 1975–1976 in solidarity with the independence movement in the Basque Country. This short-lived publication and its historical context are described in this article.1 Euskadi-bulletinen was published by Askatasuna ('freedom' in Basque), which described itself as a “committee for solidarity with the Basque people's struggle for freedom and socialism (1975:1, p. 24). “Euskadi” in the bulletin's title did not only refer to the three provinces Araba, Biscay and Gipuzkoa in northern Spain, but also to the neighbouring region Navarre and the three historical provinces Lapurdi, Lower Navarre and Zuberoa in southwestern France. This could be seen directly on the covers which all are decorated with maps including all seven provinces. -

Badihardugu Katalogoa07:Badihardugu Katalogoa

Deba Ibarreko euskarazko argitalpenak Deba Ibarreko Katalogoa Deba Ibarreko katalogoa 2 Argitaratzailea: BADIHARDUGU Deba Ibarreko Euskara Elkartea Urkizu 11, behea. 20600 Eibar Tel: 943 12 17 75 E-posta: [email protected] www.badihardugu.com Diseinua, maketazioa eta inprimaketa: Gertu, Oñati. Lege Gordailua: SS-1552-2007 Badihardugu Euskara Elkartea Deba Ibarreko katalogoa Badihardugu Euskara Elkartea Deba Ibarretik euskararen herrira Zuazo, Koldo eta Badihardugu Euskara Elkartea. 2002. Badihardugu Euskara Elkartea. ISBN: 84-607-4479-5. Prezioa: 12 € 3 Berbeta Berua Telleria, Alberto. 2003. Badihardugu Euskara Elkartea. ISBN: 84-607-6843-0. Prezioa: 10 € Ahozko jarduna hobetzeko proposamenak Plazaola, Estepan; Agirregabiria, Karmele; Bikuña, Karmen. 2005. Badihardugu Euskara Elkartea. ISBN: 84-609-5289-4. Prezioa: 10 € Deba ibarreko euskara. Dialektologia eta Tokiko batua Zuazo, Koldo. 2006. Badihardugu Euskara Elkartea. ISBN: 84-611-3813-9. Prezioa: 12 € Badihardugu Euskara Elkartea Deba Ibarreko katalogoa Oñatiko aditz-taulak Oñatiko Bedita Larrakoetxea udal euskaltegia. 2005. Badihardugu Euskara Elkartea. ISBN: 84-609-8259-9. Prezioa: 3 € Eibarko aditz-taulak Agirrebeña, Aintzane. 2005. Badihardugu Euskara Elkartea. ISBN: 84-609-8259-9. Prezioa: 3 € Bergarako aditz-taulak Elexpuru, Juan Martin. 2006. 4 Badihardugu Euskara Elkartea. ISBN: 84-611-3812-0. Prezioa: 3 € Elgoibarko aditz-taulak Makazaga, Jesus Mari. 2006. Badihardugu Euskara Elkartea. ISBN: 84-611-3756-6. Prezioa: 3 € Elgetako aditz-taulak Arantzabal, Iban. 2007. Badihardugu Euskara Elkartea. Prezioa: 3 € Aretxabaleta, Eskoriatza eta Leintz Gatzagako aditz-taulak Agirregabiria, Karmele; Iñurrategi, Larraitz eta Fdz. de Arroiabe, Nuria. 2007. Badihardugu Euskara Elkartea. Prezioa: 3 € Deba ibarreko hizkeren mapa Badihardugu Euskara Elkartea. 2005. L.G.: SS-1588/05. Prezioa: 3 € Euskalkian idazteko irizpideak Badihardugu Euskara Elkartea. -

Catalan Modernism and Vexillology

Catalan Modernism and Vexillology Sebastià Herreros i Agüí Abstract Modernism (Modern Style, Modernisme, or Art Nouveau) was an artistic and cultural movement which flourished in Europe roughly between 1880 and 1915. In Catalonia, because this era coincided with movements for autonomy and independence and the growth of a rich bourgeoisie, Modernism developed in a special way. Differing from the form in other countries, in Catalonia works in the Modern Style included many symbolic elements reflecting the Catalan nationalism of their creators. This paper, which follows Wladyslaw Serwatowski’s 20 ICV presentation on Antoni Gaudí as a vexillographer, studies other Modernist artists and their flag-related works. Lluís Domènech i Montaner, Josep Puig i Cadafalch, Josep Llimona, Miquel Blay, Alexandre de Riquer, Apel·les Mestres, Antoni Maria Gallissà, Joan Maragall, Josep Maria Jujol, Lluís Masriera, Lluís Millet, and others were masters in many artistic disciplines: Architecture, Sculpture, Jewelry, Poetry, Music, Sigillography, Bookplates, etc. and also, perhaps unconsciously, Vexillography. This paper highlights several flags and banners of unusual quality and national significance: Unió Catalanista, Sant Lluc, CADCI, Catalans d’Amèrica, Ripoll, Orfeó Català, Esbart Català de Dansaires, and some gonfalons and flags from choral groups and sometent (armed civil groups). New Banner, Basilica of the Monastery of Santa Maria de Ripoll Proceedings of the 24th International Congress of Vexillology, Washington, D.C., USA 1–5 August 2011 © 2011 North American Vexillological Association (www.nava.org) 506 Catalan Modernism and Vexillology Background At the 20th International Conference of Vexillology in Stockholm in 2003, Wladyslaw Serwatowski presented the paper “Was Antonio Gaudí i Cornet (1852–1936) a Vexillographer?” in which he analyzed the vexillological works of the Catalan architectural genius Gaudí. -

Pais Vasco 2018

The País Vasco Maribel’s Guide to the Spanish Basque Country © Maribel’s Guides for the Sophisticated Traveler ™ August 2018 [email protected] Maribel’s Guides © Page !1 INDEX Planning Your Trip - Page 3 Navarra-Navarre - Page 77 Must Sees in the País Vasco - Page 6 • Dining in Navarra • Wine Touring in Navarra Lodging in the País Vasco - Page 7 The Urdaibai Biosphere Reserve - Page 84 Festivals in the País Vasco - Page 9 • Staying in the Urdaibai Visiting a Txakoli Vineyard - Page 12 • Festivals in the Urdaibai Basque Cider Country - Page 15 Gernika-Lomo - Page 93 San Sebastián-Donostia - Page 17 • Dining in Gernika • Exploring Donostia on your own • Excursions from Gernika • City Tours • The Eastern Coastal Drive • San Sebastián’s Beaches • Inland from Lekeitio • Cooking Schools and Classes • Your Western Coastal Excursion • Donostia’s Markets Bilbao - Page 108 • Sociedad Gastronómica • Sightseeing • Performing Arts • Pintxos Hopping • Doing The “Txikiteo” or “Poteo” • Dining In Bilbao • Dining in San Sebastián • Dining Outside Of Bilbao • Dining on Mondays in Donostia • Shopping Lodging in San Sebastián - Page 51 • Staying in Bilbao • On La Concha Beach • Staying outside Bilbao • Near La Concha Beach Excursions from Bilbao - Page 132 • In the Parte Vieja • A pretty drive inland to Elorrio & Axpe-Atxondo • In the heart of Donostia • Dining in the countryside • Near Zurriola Beach • To the beach • Near Ondarreta Beach • The Switzerland of the País Vasco • Renting an apartment in San Sebastián Vitoria-Gasteiz - Page 135 Coastal -

The Basques of Lapurdi, Zuberoa, and Lower Navarre Their History and Their Traditions

Center for Basque Studies Basque Classics Series, No. 6 The Basques of Lapurdi, Zuberoa, and Lower Navarre Their History and Their Traditions by Philippe Veyrin Translated by Andrew Brown Center for Basque Studies University of Nevada, Reno Reno, Nevada This book was published with generous financial support obtained by the Association of Friends of the Center for Basque Studies from the Provincial Government of Bizkaia. Basque Classics Series, No. 6 Series Editors: William A. Douglass, Gregorio Monreal, and Pello Salaburu Center for Basque Studies University of Nevada, Reno Reno, Nevada 89557 http://basque.unr.edu Copyright © 2011 by the Center for Basque Studies All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America Cover and series design © 2011 by Jose Luis Agote Cover illustration: Xiberoko maskaradak (Maskaradak of Zuberoa), drawing by Paul-Adolph Kaufman, 1906 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Veyrin, Philippe, 1900-1962. [Basques de Labourd, de Soule et de Basse Navarre. English] The Basques of Lapurdi, Zuberoa, and Lower Navarre : their history and their traditions / by Philippe Veyrin ; with an introduction by Sandra Ott ; translated by Andrew Brown. p. cm. Translation of: Les Basques, de Labourd, de Soule et de Basse Navarre Includes bibliographical references and index. Summary: “Classic book on the Basques of Iparralde (French Basque Country) originally published in 1942, treating Basque history and culture in the region”--Provided by publisher. ISBN 978-1-877802-99-7 (hardcover) 1. Pays Basque (France)--Description and travel. 2. Pays Basque (France)-- History. I. Title. DC611.B313V513 2011 944’.716--dc22 2011001810 Contents List of Illustrations..................................................... vii Note on Basque Orthography......................................... -

Basque Studies

Center for BasqueISSN: Studies 1537-2464 Newsletter Center for Basque Studies N E W S L E T T E R Basque Literature Series launched at Frankfurt Book Fair FALL Reported by Mari Jose Olaziregi director of Literature across Frontiers, an 2004 organization that promotes literature written An Anthology of Basque Short Stories, the in minority languages in Europe. first publication in the Basque Literature Series published by the Center for NUMBER 70 Basque Studies, was presented at the Frankfurt Book Fair October 19–23. The Basque Editors’ Association / Euskal Editoreen Elkartea invited the In this issue: book’s compiler, Mari Jose Olaziregi, and two contributors, Iban Zaldua and Lourdes Oñederra, to launch the Basque Literature Series 1 book in Frankfurt. The Basque Government’s Minister of Culture, Boise Basques 2 Miren Azkarate, was also present to Kepa Junkera at UNR 3 give an introductory talk, followed by Olatz Osa of the Basque Editors’ Jauregui Archive 4 Association, who praised the project. Kirmen Uribe performs Euskal Telebista (Basque Television) 5 was present to record the event and Highlights 6 interview the participants for their evening news program. (from left) Lourdes Oñederra, Iban Zaldua, and Basque Country Tour 7 Mari Jose Olaziregi at the Frankfurt Book Fair. Research awards 9 Prof. Olaziregi explained to the [photo courtesy of I. Zaldua] group that the aim of the series, Ikasi 2005 10 consisting of literary works translated The following day the group attended the Studies Abroad in directly from Basque to English, is “to Fair, where Ms. Olaziregi met with editors promote Basque literature abroad and to and distributors to present the anthology and the Basque Country 11 cross linguistic and cultural borders in order discuss the series. -

Haur Eta Gazte Literatura Gikda.Pdf

Haur eta Gazte Literatura gida 2001-2014 -liburu oso gomendagarriak 1 Haur eta Gazte Literatura gida 2001-2014 -liburu oso gomendagarriak Argitaratzailea: MONDRAGON UNIBERTSITATEA Humanitate eta Hezkuntza Zientzien Fakultatea Erredakzioa Idazkaritza: MONDRAGON UNIBERTSITATEA Humanitate eta Hezkuntza Zientzien Fakultateko Haur Liburu Mintegia Dorleta Auzoa, z/g 20540 - Eskoriatza Tfnoa: 943 714 157 - Faxa: 943 714 032 E-mail: [email protected] www.mondragon.edu/huhezi 2 Haur eta Gazte Literatura gida 2001-2014 -liburu oso gomendagarriak SARRERA Haur eta Gazte Literatura, 2001-2014 2001-2014 Irakur Gida talde zabal baten lan jarraituaren eta 1.614 libururen irakurketa konpartituaren emaitza da. Lan horretan, Haur Liburu Mintegiak gomendatutako liburuak bildu ditugu, bakoitzari dagokion iruzkin laburrarekin batera, azken 14 urteotan argitaratu diren gidetatik hartuta. Urte hauetan asko ikasi dugu, eta, horrek liburuak aztertzeko eta aukeratzeko irizpideak fintzera eraman gaitu. Ondorioz, konturatzen gara orain dela 10 urte gomendatuko libururen bat gaur egun ez genukeela gomendatuko, eta, baita ere, beste modu batean idatziko genukeela hainbat iruzkin. Hala eta guztiz, liburu gomendagarriak urteroko gidetan argitaratu ziren moduan bildu ditugu, eta idatzi ziren moduan mantendu ditugu iruzkinak. Kuriositate moduan: irakurritako liburuetatik, 686 jatorriz euskaraz argitaratuak dira; 184, emakumeek idatzitakoak; eta emakume euskaldunek idatzitakoak, berriz, 58. Guztira, 192 izan dira gomendatu eta iruzkindutako liburuak. Gida hau ontzeko edizio lanean iruzkin guztiak irakurri ditugu berriz, eta gu geu harrituta gelditu gara zenbat liburu on daukagun euskaraz, eta eskura. Denek ez dute balio bera, baina badaude liburu oso onak, eta, iruzkinak jarraituz, irakurlea jabetuko da horietako askoren balioaz. Bestalde, beti bezala, iruzkinean jartzen den adina orientazio bat baino ez da; izan ere, garapen-erritmoak, haurren zaletasunak eta testuinguruak, besteak beste, sailkaezinak baitira. -

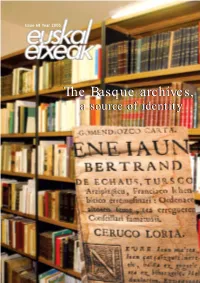

The Basquebasque Archives,Archives, Aa Sourcesource Ofof Identityidentity TABLE of CONTENTS

Issue 68 Year 2005 TheThe BasqueBasque archives,archives, aa sourcesource ofof identityidentity TABLE OF CONTENTS GAURKO GAIAK / CURRENT EVENTS: The Basque archives, a source of identity Issue 68 Year 3 • Josu Legarreta, Basque Director of Relations with Basque Communities. The BasqueThe archives,Basque 4 • An interview with Arantxa Arzamendi, a source of identity Director of the Basque Cultural Heritage Department 5 • The Basque archives can be consulted from any part of the planet 8 • Classification and digitalization of parish archives 9 • Gloria Totoricagüena: «Knowledge of a common historical past is essential to maintaining a people’s signs of identity» 12 • Urazandi, a project shining light on Basque emigration 14 • Basque periodicals published in Venezuela and Mexico Issue 68. Year 2005 ARTICLES 16 • The Basque "Y", a train on the move 18 • Nestor Basterretxea, sculptor. AUTHOR A return traveller Eusko Jaurlaritza-Kanpo Harremanetarako Idazkaritza 20 • Euskaditik: The Bishop of Bilbao, elected Nagusia President of the Spanish Episcopal Conference Basque Government-General 21 • Euskaditik: Election results Secretariat for Foreign Action 22 • Euskal gazteak munduan / Basque youth C/ Navarra, 2 around the world 01007 VITORIA-GASTEIZ Nestor Basterretxea Telephone: 945 01 7900 [email protected] DIRECTOR EUSKAL ETXEAK / ETXEZ ETXE Josu Legarreta Bilbao COORDINATION AND EDITORIAL 24 • Proliferation of programs in the USA OFFICE 26 • Argentina. An exhibition for the memory A. Zugasti (Kazeta5 Komunikazioa) 27 • Impressions of Argentina