UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE 'Twixt and 'Tween A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dragon Magazine

May 1980 The Dragon feature a module, a special inclusion, or some other out-of-the- ordinary ingredient. It’s still a bargain when you stop to think that a regular commercial module, purchased separately, would cost even more than that—and for your three bucks, you’re getting a whole lot of magazine besides. It should be pointed out that subscribers can still get a year’s worth of TD for only $2 per issue. Hint, hint . And now, on to the good news. This month’s kaleidoscopic cover comes to us from the talented Darlene Pekul, and serves as your p, up and away in May! That’s the catch-phrase for first look at Jasmine, Darlene’s fantasy adventure strip, which issue #37 of The Dragon. In addition to going up in makes its debut in this issue. The story she’s unfolding promises to quality and content with still more new features this be a good one; stay tuned. month, TD has gone up in another way: the price. As observant subscribers, or those of you who bought Holding down the middle of the magazine is The Pit of The this issue in a store, will have already noticed, we’re now asking $3 Oracle, an AD&D game module created by Stephen Sullivan. It for TD. From now on, the magazine will cost that much whenever we was the second-place winner in the first International Dungeon Design Competition, and after looking it over and playing through it, we think you’ll understand why it placed so high. -

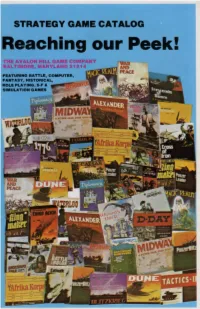

Ah-80Catalog-Alt

STRATEGY GAME CATALOG I Reaching our Peek! FEATURING BATTLE, COMPUTER, FANTASY, HISTORICAL, ROLE PLAYING, S·F & ......\Ci l\\a'C:O: SIMULATION GAMES REACHING OUR PEEK Complexity ratings of one to three are introduc tory level games Ratings of four to six are in Wargaming can be a dece1v1ng term Wargamers termediate levels, and ratings of seven to ten are the are not warmongers People play wargames for one advanced levels Many games actually have more of three reasons . One , they are interested 1n history, than one level in the game Itself. having a basic game partlcularly m1l11ary history Two. they enroy the and one or more advanced games as well. In other challenge and compet111on strategy games afford words. the advance up the complexity scale can be Three. and most important. playing games is FUN accomplished within the game and wargaming is their hobby The listed playing times can be dece1v1ng though Indeed. wargaming 1s an expanding hobby they too are presented as a guide for the buyer Most Though 11 has been around for over twenty years. 11 games have more than one game w1th1n them In the has only recently begun to boom . It's no [onger called hobby, these games w1th1n the game are called JUSt wargam1ng It has other names like strategy gam scenarios. part of the total campaign or battle the ing, adventure gaming, and simulation gaming It game 1s about Scenarios give the game and the isn 't another hoola hoop though. By any name, players variety Some games are completely open wargam1ng 1s here to stay ended These are actually a game system. -

TODD LOCKWOOD the Neverwinter™ Saga, Book IV the LAST THRESHOLD ©2013 Wizards of the Coast LLC

ThE ™ SAgA IVBooK COVER ART TODD LOCKWOOD The Neverwinter™ Saga, Book IV THE LAST THRESHOLD ©2013 Wizards of the Coast LLC. This book is protected under the copyright laws of the United States of America. Any reproduction or unau- thorized use of the material or artwork contained herein is prohibited without the express written permission of Wizards of the Coast LLC. Published by Wizards of the Coast LLC. Manufactured by: Hasbro SA, Rue Emile-Boéchat 31, 2800 Delémont, CH. Represented by Hasbro Europe, 2 Roundwood Ave, Stockley Park, Uxbridge, Middlesex, UB11 1AZ, UK. DUNGEONS & DRAGONS, D&D, WIZARDS OF THE COAST, NEVERWINTER, FORGOTTEN REALMS, and their respective logos are trademarks of Wizards of the Coast LLC in the USA and other countries. All characters in this book are fictitious. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, is purely coin- cidental. All Wizards of the Coast characters and their distinctive likenesses are property of Wizards of the Coast LLC. PRINTED IN THE U.S.A. Cover art by Todd Lockwood First Printing: March 2013 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 ISBN: 978-0-7869-6364-5 620A2245000001 EN Cataloging-in-Publication data is on file with the Library of Congress For customer service, contact: U.S., Canada, Asia Pacific, & Latin America: Wizards of the Coast LLC, P.O. Box 707, Renton, WA 98057- 0707, +1-800-324-6496, www.wizards.com/customerservice U.K., Eire, & South Africa: Wizards of the Coast LLC, c/o Hasbro UK Ltd., P.O. Box 43, Newport, NP19 4YD, UK, Tel: +08457 12 55 99, Email: [email protected] All other countries: Wizards of the Coast p/a Hasbro Belgium NV/SA, Industrialaan 1, 1702 Groot- Bijgaarden, Belgium, Tel: +32.70.233.277, Email: [email protected] Visit our web site at www.dungeonsanddragons.com Prologue The Year of the Reborn Hero (1463 DR) ou cannot presume that this creature is natural, in any sense of Ythe word,” the dark-skinned Shadovar woman known as the Shifter told the old graybeard. -

The AVALON HILL

$2.50 The AVALON HILL July-August 1981 Volume 18, Number 2 3 A,--LJ;l.,,,, GE!Jco L!J~ &~~ 2~~ BRIDGE 8-1-2 4-2-3 4-4 4-6 10-4 5-4 This revision of a classic game you've long awaited is the culmination What's Inside . .. of five years of intensive research and playtest. The resuit. we 22" x 28" Fuli-color Mapboard of Ardennes Battlefield believe, will provide you pleasure for many years to come. Countersheet with 260 American, British and German Units For you historical buffs, BATTLE OF THE BULGE is the last word in countersheet of 117 Utility Markers accuracy. Official American and German documents, maps and Time Record Card actual battle reports (many very difficult to obtain) were consuited WI German Order of Appearance Card to ensure that both the order of battle and mapboard are correct Allied Order of Appearance Card to the last detail. Every fact was checked and double-checked. Rules Manual The reSUlt-you move the actual units over the same terrain that One Die their historical counterparts did in 1944. For the rest of you who are looking for a good, playable game, BATTLE OF THE BULGE is an operational recreation of the famous don't look any further. "BULGE" was designed to be FUN! This Ardennes battle of December, 1944-January, 1945. means a simple, streamlined playing system that gives you time to Each unit represents one of the regiments that actually make decisions instead of shuffling paper. The rules are short and participated (or might have participated) in the battle. -

Page 1 of 279 FLORIDA LRC DECISIONS

FLORIDA LRC DECISIONS. January 01, 2012 to Date 2019/06/19 TITLE / EDITION OR ISSUE / AUTHOR OR EDITOR ACTION RULE MEETING (Titles beginning with "A", "An", or "The" will be listed according to the (Rejected / AUTH. DATE second/next word in title.) Approved) (Rejectio (YYYY/MM/DD) ns) 10 DAI THOU TUONG TRUNG QUAC. BY DONG VAN. REJECTED 3D 2017/07/06 10 DAI VAN HAO TRUNG QUOC. PUBLISHER NHA XUAT BAN VAN HOC. REJECTED 3D 2017/07/06 10 POWER REPORTS. SUPPLEMENT TO MEN'S HEALTH REJECTED 3IJ 2013/03/28 10 WORST PSYCHOPATHS: THE MOST DEPRAVED KILLERS IN HISTORY. BY VICTOR REJECTED 3M 2017/06/01 MCQUEEN. 100 + YEARS OF CASE LAW PROVIDING RIGHTS TO TRAVEL ON ROADS WITHOUT A APPROVED 2018/08/09 LICENSE. 100 AMAZING FACTS ABOUT THE NEGRO. BY J. A. ROGERS. APPROVED 2015/10/14 100 BEST SOLITAIRE GAMES. BY SLOANE LEE, ETAL REJECTED 3M 2013/07/17 100 CARD GAMES FOR ALL THE FAMILY. BY JEREMY HARWOOD. REJECTED 3M 2016/06/22 100 COOL MUSHROOMS. BY MICHAEL KUO & ANDY METHVEN. REJECTED 3C 2019/02/06 100 DEADLY SKILLS SURVIVAL EDITION. BY CLINT EVERSON, NAVEL SEAL, RET. REJECTED 3M 2018/09/12 100 HOT AND SEXY STORIES. BY ANTONIA ALLUPATO. © 2012. APPROVED 2014/12/17 100 HOT SEX POSITIONS. BY TRACEY COX. REJECTED 3I 3J 2014/12/17 100 MOST INFAMOUS CRIMINALS. BY JO DURDEN SMITH. APPROVED 2019/01/09 100 NO- EQUIPMENT WORKOUTS. BY NEILA REY. REJECTED 3M 2018/03/21 100 WAYS TO WIN A TEN-SPOT. BY PAUL ZENON REJECTED 3E, 3M 2015/09/09 1000 BIKER TATTOOS. -

Twixt Ocean and Pines : the Seaside Resort at Virginia Beach, 1880-1930 Jonathan Mark Souther

University of Richmond UR Scholarship Repository Master's Theses Student Research 5-1996 Twixt ocean and pines : the seaside resort at Virginia Beach, 1880-1930 Jonathan Mark Souther Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.richmond.edu/masters-theses Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Souther, Jonathan Mark, "Twixt ocean and pines : the seaside resort at Virginia Beach, 1880-1930" (1996). Master's Theses. Paper 1037. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Research at UR Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of UR Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TWIXT OCEAN AND PINES: THE SEASIDE RESORT AT VIRGINIA BEACH, 1880-1930 Jonathan Mark Souther Master of Arts University of Richmond, 1996 Robert C. Kenzer, Thesis Director This thesis descnbes the first fifty years of the creation of Virginia Beach as a seaside resort. It demonstrates the importance of railroads in promoting the resort and suggests that Virginia Beach followed a similar developmental pattern to that of other ocean resorts, particularly those ofthe famous New Jersey shore. Virginia Beach, plagued by infrastructure deficiencies and overshadowed by nearby Ocean View, did not stabilize until its promoters shifted their attention from wealthy northerners to Tidewater area residents. After experiencing difficulties exacerbated by the Panic of 1893, the burning of its premier hotel in 1907, and the hesitation bred by the Spanish American War and World War I, Virginia Beach enjoyed robust growth during the 1920s. While Virginia Beach is often perceived as a post- World War II community, this thesis argues that its prewar foundation was critical to its subsequent rise to become the largest city in Virginia. -

Ah-88Catalog-Alt

GAMES and PARTS PRICE LIST EFFECTIVE OCTOBER 26, 1988 ICHARGE' Ordering Information 2 ~®;: Role-Playlng Games 1~ 3 -M.-. Fantasy and Science Fiction Games I 3 .-I ff.i I . Mllltary Slmulatlons ~ 4 k-r.· \ .. 7 Strategy /Wargames I 5 (~[~i\l\ri The General Magazine I 7 tt1IJ. Miscellaneous Merchandise I ~ 8 ~-.....Leisure Tlme/Famlly Games I 8 ~ General Interest Games ~ 9 JC. Jigsaw Puzzles 9 ~XJ Sports Illustrated Games 1~9 Lh Discontinued Software micl"ocomputel" ~cmes 1 o Microcomputer Games micl"ocomputel" ~cmes 11 ~ Discontinued Parts List I 12 ~. How to Compute Shipping 16 Telephone Ordering/Customer Services 16 1989 AVALON HILL CHAMPIONSHIP CONVENTION •The national championships for numerous Avalon Hill games will be held sometime in 1989 somewhere in the Baltimore, MD region. If you would like to be kept informed of the games being offered in these national tournaments, send a stamped, self-addressed envelope to: AH Championships, 4517 Harford Rd., Baltimore, MD 21214. We will notify you of the time, place and games involved when details are finalized. For Credit Card Orders Call TOLL FREE 1·800·638·9292 Numbered circles represent wargame complexity rating on a scale of 1 to 10: 10 being the most complex. ---ROLE PLAYING GAMES THIS IS a complete listing of all current and discon HOW TO COMPUTE SHIPPING: tinued games and their parts listed in group classifica BILLAPPLELANE 10.00 See the last page of this booklet. RUNEOUEST-A Game of Action*, Imagination&VlLOI v.~~....~ ·: tions. Parts which are shaded do not come with the IN A RUSH? We can cut the red tape and handle your and Adventure SNAKEPIPE HOLLOW 10.00 (/!?!! game. -

Twixt Land & Sea Tales

Twixt Land & Sea Tales A SMILE OF FORTUNE—HARBOUR STORY Ever since the sun rose I had been looking ahead. The ship glided gently in smooth water. After a sixty days’ passage I was anxious to make my landfall, a fertile and beautiful island of the tropics. The more enthusiastic of its inhabitants delight in describing it as the “Pearl of the Ocean.” Well, let us call it the “Pearl.” It’s a good name. A pearl distilling much sweetness upon the world. This is only a way of telling you that first-rate sugar-cane is grown there. All the population of the Pearl lives for it and by it. Sugar is their daily bread, as it were. And I was coming to them for a cargo of sugar in the hope of the crop having been good and of the freights being high. Mr. Burns, my chief mate, made out the land first; and very soon I became entranced by this blue, pinnacled apparition, almost transparent against the light of the sky, a mere emanation, the astral body of an island risen to greet me from afar. It is a rare phenomenon, such a sight of the Pearl at sixty miles off. And I wondered half seriously whether it was a good omen, whether what would meet me in that island would be as luckily exceptional as this beautiful, dreamlike vision so very few seamen have been privileged to behold. But horrid thoughts of business interfered with my enjoyment of an accomplished passage. I was anxious for success and I wished, too, to do justice to the flattering latitude of my owners’ instructions contained in one noble phrase: “We leave it to you to do the best you can with the ship.” . -

Cypress Hill MP3 Звездная Серия Mp3, Flac, Wma

Cypress Hill MP3 Звездная Серия mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Hip hop Album: MP3 Звездная Серия Country: Russia Released: 2005 Style: Gangsta MP3 version RAR size: 1552 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1116 mb WMA version RAR size: 1536 mb Rating: 4.9 Votes: 753 Other Formats: AA MP2 AU AIFF WAV VOC AC3 Tracklist Cypress Hill 1 Pigs 2:51 2 How I Could Just Kill A Man 4:08 3 Hand On The Pump 4:03 4 Hole In The Head 3:33 5 Ultraviolet Dreams 0:41 6 Light Another 3:17 7 The Phuncky Feel One 3:28 8 Break It Up 1:07 9 Real Estate 3:45 10 Stoned Is The Way Of The Walk 2:46 11 Psychobetabuckdown 2:59 12 Something For The Blunted 1:15 13 Latin Lingo 3:59 14 The Funky Cypress Hill Shit 4:01 15 Tres Equis 1:54 16 Born To Get Busy 3:00 Black Sunday 17 I Wanna Get High 2:54 18 I Ain't Goin Out Like That 4:28 19 Insane In The Brain 3:29 20 When The Shit Goes Down 3:08 21 Lick A Shot 3:23 22 Cock The Hammer 4:25 23 Interlude 1:17 24 Lil' Putos 3:40 25 Legalize It 0:47 26 Hits From The Bong 2:40 27 What Go Around Come Around, Kid 3:42 28 A To The K 3:27 29 Hand On The Glock 3:32 30 Break Em Off Some 2:44 Temples Of Boom 31 Spark Another Owl 3:40 32 Throw Your Set In The Air 4:08 33 Stoned Raiders 2:54 34 Illusions 4:28 35 Killa Hill Niggas 4:02 36 Boom Biddy Bye-Bye 4:04 37 No Rest For The Wicked 5:03 38 Make A Move 4:33 39 Killafornia 2:56 40 Funk Freakers 3:14 41 Locotes 3:37 42 Red Light Visions 1:46 43 Strictly Hip-Hop 4:33 44 Everybody Must Get Stoned 3:04 IV 45 Looking Through The Eye Of A Pig 4:03 46 Checkmate 3:37 47 From The Window -

Fall 2008 Issue

www.diplomacyworld.net Science Fiction and Fantasy in Diplomacy Notes from the Editor Welcome back to Diplomacy World, your hobby flagship columns to the sense of community and family so many since Walt Buchanan founded the zine in 1974! And, segments of the hobby had. Fiction, hilarious press, despite numerous near-death experiences, close calls, take-offs and send-ups, serious debate, triumph and financial insolvency, and predictions of doom, we’re still tragedy; they can all be found here, along with un- here, more than 100 issues later, bringing you the best obscured looks at the world as it changed over the last articles, hobby news, and opinions that we know how to 40+ years. I’m not sure how much I’ll be writing about produce. this project in future issues of Diplomacy World, but if nothing else it gave me the material for an article this Speaking of Diplomacy World’s past glories, this is as time, about the first real hobby scandal. If you’d like to good a place as any to mention that we have FINALLY read some of these zines, you can find them in the completed the task of scanning and posting every single Postal Diplomacy Zine Archive section at: issue of Diplomacy World ever produced. This includes every issue from #1 through #103 (the one you’re http://www.whiningkentpigs.com/DW/ reading now) plus the fake issue #40 and the full results of the Demo Game “Flapjack” which were never Incidentally, if you’d like to be kept up-to-date on what completely published. -

Sample Some of This

Sample Some Of This, Sample Some Of That (169) ✔ KEELY SMITH / I Wish You Love [Capitol (LP)] JEHST / Bluebells [Low Life (EP)] RAMSEY LEWIS TRIO / Concierto De Aranjuez [Cadet (LP)] THE COUP / The Liberation Of Lonzo Williams [Wild Pitch (12")] EYEDEA & ABILITIES / E&A Day [Epitaph (LP)] CEE-KNOWLEDGE f/ Sun Ra's Arkestra / Space Is The Place [Counterflow (12")] JOHN DANKWORTH & HIS ORCHESTRA / Bernie's Tune ("Off Duty", O.S.T.) [Fontana (LP)] COMMON & MARK THE 45 KING / Car Horn (Madlib remix) [Madlib (LP)] GANG STARR / All For Da Ca$h [Cooltempo/Noo Trybe (LP)] JOHN DANKWORTH & HIS ORCHESTRA / Theme From "Return From The Ashes", O.S.T. [RCA (LP)] 7 NOTAS 7 COLORES / Este Es Un Trabajo Para Mis… [La Madre (LP)] QUASIMOTO / Astronaut [Antidote (12")] DJ ROB SWIFT / The Age Of Television [Om (LP)] JOHN DANKWORTH & HIS ORCHESTRA / Look Stranger (From BBC-TV Series) [RCA (LP)] THE LARGE PROFESSOR & PETE ROCK / The Rap World [Big Beat/Atlantic (LP)] JOHN DANKWORTH & HIS ORCHESTRA / Two-Piece Flower [Montana (LP)] GANG STARR f/ Inspectah Deck / Above The Clouds [Noo Trybe (LP)] Sample Some Of This, Sample Some Of That (168) ✔ GABOR SZABO / Ziggidy Zag [Salvation (LP)] MAKEBA MOONCYCLE / Judgement Day [B.U.K.A. (12")] GABOR SZABO / The Look Of Love [Buddah (LP)] DIAMOND D & SADAT X f/ C-Low, Severe & K-Terrible / Feel It [H.O.L.A. (12")] GABOR SZABO / Love Theme From "Spartacus" [Blue Thumb (LP)] BLACK STAR f/ Weldon Irvine / Astronomy (8th Light) [Rawkus (LP)] GABOR SZABO / Sombrero Man [Blue Thumb (LP)] ACEYALONE / The Hunt [Project Blowed (LP)] GABOR SZABO / Gloomy Day [Mercury (LP)] HEADNODIC f/ The Procussions / The Drive [Tres (12")] GABOR SZABO / The Biz [Orpheum Musicwerks (LP)] GHETTO PHILHARMONIC / Something 2 Funk About [Tuff City (LP)] GABOR SZABO / Macho [Salvation (LP)] B.A. -

Evolution Gaming Memes

Tzolk'in Mystic Vale Kingdom Builder *Variable Setup* CodeNames (Card Building) *Variable Setup* King of Tokyo Tiananmen (Worker Placement) Dixit (Word Game) (Press Your Luck) (Area Control) Hanabi Secret Hitler *Shifting Alliances* *Cyclic vs. Radial Connection* (Win by Points) (Secret Information) (Uses Moderator) 2016 (Area Points) (Co-Operative) (Blind Moderator) (Press Your Luck) (Educational Game - History) 2012 (Perception) (Secret Information) Caylus (Connectivity Points) (Secret Information) (Secret Alliances) (Multiple Paths to Victory) (Asymmetric Player Powers) 2010 (Deduction Win Condition) (Win by Points) (Asymmetric Player Powers) 2011 (Worker Placement) Star Realms PatchWork (Pure Strategy) 2016 2013 Dvonn 2012 2016 (1D Linear Board) (Deck Building) (Cover the Board) 2014 (Shrinking Board) (Win by Points) (Card Synergy) 2014 2005 (~Hexagonal Grid) 2014 (Minimal Rules) Calculus (Neutral Pieces) (Continuous Board) Thurn and Taxis (Strategic Perception) (2D Board) (Area Control) WYPS Power Grid Prime Climb (Stackable Pieces - Top Piece Controls) (Edge to Edge Connection) Carcassonne (Catch-Up Mechanic) (Area Points) Lost Cities (Word Game) (Educational Game - Mathematics) 2001 (Minimal Rules) (Worker Placement) (Bidding) Dominion *Star (Connectivity Points) (Suits) (Hexagonal Grid) (Random Strategic Movement) 1997 (Revealed Board) (Map) *Deck Building* (2D Board) (Win by Points) (Win by Points) (Edge to Edge Connection) The Resistance / Avalon Coup (1D Linear Board) 2000 2004 (Card Synergy) (Minimalist Rules) 2006 1999 2009