Views Even Further

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Byzantine Liturgy and The

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Byzantine Liturgy and the Primary Chronicle A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Slavic Languages and Literatures by Sean Delaine Griffin 2014 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Byzantine Liturgy and the Primary Chronicle by Sean Delaine Griffin Doctor of Philosophy in Slavic Languages and Literatures University of California, Los Angeles, 2014 Professor Gail Lenhoff, Chair The monastic chroniclers of medieval Rus’ lived in a liturgical world. Morning, evening and night they prayed the “divine services” of the Byzantine Church, and this study is the first to examine how these rituals shaped the way they wrote and compiled the Povest’ vremennykh let (Primary Chronicle, ca. 12th century), the earliest surviving East Slavic historical record. My principal argument is that several foundational accounts of East Slavic history—including the tales of the baptism of Princess Ol’ga and her burial, Prince Vladimir’s conversion, the mass baptism of Rus’, and the martyrdom of Princes Boris and Gleb—have their source in the feasts of the liturgical year. The liturgy of the Eastern Church proclaimed a distinctively Byzantine myth of Christian origins: a sacred narrative about the conversion of the Roman Empire, the glorification of the emperor Constantine and empress Helen, and the victory of Christianity over paganism. In the decades following the conversion of Rus’, the chroniclers in Kiev learned these narratives from the church services and patterned their own tales of Christianization after them. The ii result was a myth of Christian origins for Rus’—a myth promulgated even today by the Russian Orthodox Church—that reproduced the myth of Christian origins for the Eastern Roman Empire articulated in the Byzantine rite. -

Christianity Unveiled; Being an Examination of the Principles and Effects of the Christian Religion

Christianity Unveiled; Being An Examination Of The Principles And Effects Of The Christian Religion by Paul Henri d’Holbach - 1761 [1819 translation by W. M. Johnson] CONTENTS. A LETTER from the Author to a Friend. CHAPTER I. - Of the necessity of an Inquiry respecting Religion, and the Obstacles which are met in pursuing this Inquiry. CHAPTER II. - Sketch of the History of the Jews. CHAPTER III. - Sketch of the History of the Christian Religion. CHAPTER IV. - Of the Christian Mythology, or the Ideas of God and his Conduct, given us by the Christian Religion. CHAPTER V. - Of Revelation. CHAPTER VI. - Of the Proofs of the Christian Religion, Miracles, Prophecies, and Martyrs. CHAPTER VII. - Of the Mysteries of the Christian Religion. CHAPTER VIII. - Mysteries and Dogmas of Christianity. CHAPTER IX. - Of the Rites and Ceremonies or Theurgy of the Christians. CHAPTER X. - Of the inspired Writings of the Christians. CHAPTER XI. - Of Christian Morality. CHAPTER XII. - Of the Christian Virtues. CHAPTER XIII. - Of the Practice and Duties of the Christian Religion. CHAPTER XIV. - Of the Political Effects of the Christian Religion. CHAPTER XV. - Of the Christian Church or Priesthood. CHAPTER XVI. - Conclusions. A LETTER FROM THE AUTHOR TO A FRIEND I RECEIVE, Sir, with gratitude, the remarks which you send me upon my work. If I am sensible to the praises you condescend to give it, I am too fond of truth to be displeased with the frankness with which you propose your objections. I find them sufficiently weighty to merit all my attention. He but ill deserves the title of philosopher, who has not the courage to hear his opinions contradicted. -

Dragon Magazine

May 1980 The Dragon feature a module, a special inclusion, or some other out-of-the- ordinary ingredient. It’s still a bargain when you stop to think that a regular commercial module, purchased separately, would cost even more than that—and for your three bucks, you’re getting a whole lot of magazine besides. It should be pointed out that subscribers can still get a year’s worth of TD for only $2 per issue. Hint, hint . And now, on to the good news. This month’s kaleidoscopic cover comes to us from the talented Darlene Pekul, and serves as your p, up and away in May! That’s the catch-phrase for first look at Jasmine, Darlene’s fantasy adventure strip, which issue #37 of The Dragon. In addition to going up in makes its debut in this issue. The story she’s unfolding promises to quality and content with still more new features this be a good one; stay tuned. month, TD has gone up in another way: the price. As observant subscribers, or those of you who bought Holding down the middle of the magazine is The Pit of The this issue in a store, will have already noticed, we’re now asking $3 Oracle, an AD&D game module created by Stephen Sullivan. It for TD. From now on, the magazine will cost that much whenever we was the second-place winner in the first International Dungeon Design Competition, and after looking it over and playing through it, we think you’ll understand why it placed so high. -

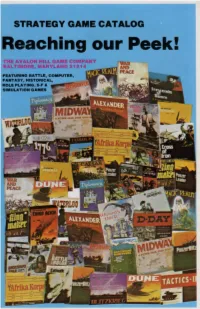

Ah-80Catalog-Alt

STRATEGY GAME CATALOG I Reaching our Peek! FEATURING BATTLE, COMPUTER, FANTASY, HISTORICAL, ROLE PLAYING, S·F & ......\Ci l\\a'C:O: SIMULATION GAMES REACHING OUR PEEK Complexity ratings of one to three are introduc tory level games Ratings of four to six are in Wargaming can be a dece1v1ng term Wargamers termediate levels, and ratings of seven to ten are the are not warmongers People play wargames for one advanced levels Many games actually have more of three reasons . One , they are interested 1n history, than one level in the game Itself. having a basic game partlcularly m1l11ary history Two. they enroy the and one or more advanced games as well. In other challenge and compet111on strategy games afford words. the advance up the complexity scale can be Three. and most important. playing games is FUN accomplished within the game and wargaming is their hobby The listed playing times can be dece1v1ng though Indeed. wargaming 1s an expanding hobby they too are presented as a guide for the buyer Most Though 11 has been around for over twenty years. 11 games have more than one game w1th1n them In the has only recently begun to boom . It's no [onger called hobby, these games w1th1n the game are called JUSt wargam1ng It has other names like strategy gam scenarios. part of the total campaign or battle the ing, adventure gaming, and simulation gaming It game 1s about Scenarios give the game and the isn 't another hoola hoop though. By any name, players variety Some games are completely open wargam1ng 1s here to stay ended These are actually a game system. -

TODD LOCKWOOD the Neverwinter™ Saga, Book IV the LAST THRESHOLD ©2013 Wizards of the Coast LLC

ThE ™ SAgA IVBooK COVER ART TODD LOCKWOOD The Neverwinter™ Saga, Book IV THE LAST THRESHOLD ©2013 Wizards of the Coast LLC. This book is protected under the copyright laws of the United States of America. Any reproduction or unau- thorized use of the material or artwork contained herein is prohibited without the express written permission of Wizards of the Coast LLC. Published by Wizards of the Coast LLC. Manufactured by: Hasbro SA, Rue Emile-Boéchat 31, 2800 Delémont, CH. Represented by Hasbro Europe, 2 Roundwood Ave, Stockley Park, Uxbridge, Middlesex, UB11 1AZ, UK. DUNGEONS & DRAGONS, D&D, WIZARDS OF THE COAST, NEVERWINTER, FORGOTTEN REALMS, and their respective logos are trademarks of Wizards of the Coast LLC in the USA and other countries. All characters in this book are fictitious. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, is purely coin- cidental. All Wizards of the Coast characters and their distinctive likenesses are property of Wizards of the Coast LLC. PRINTED IN THE U.S.A. Cover art by Todd Lockwood First Printing: March 2013 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 ISBN: 978-0-7869-6364-5 620A2245000001 EN Cataloging-in-Publication data is on file with the Library of Congress For customer service, contact: U.S., Canada, Asia Pacific, & Latin America: Wizards of the Coast LLC, P.O. Box 707, Renton, WA 98057- 0707, +1-800-324-6496, www.wizards.com/customerservice U.K., Eire, & South Africa: Wizards of the Coast LLC, c/o Hasbro UK Ltd., P.O. Box 43, Newport, NP19 4YD, UK, Tel: +08457 12 55 99, Email: [email protected] All other countries: Wizards of the Coast p/a Hasbro Belgium NV/SA, Industrialaan 1, 1702 Groot- Bijgaarden, Belgium, Tel: +32.70.233.277, Email: [email protected] Visit our web site at www.dungeonsanddragons.com Prologue The Year of the Reborn Hero (1463 DR) ou cannot presume that this creature is natural, in any sense of Ythe word,” the dark-skinned Shadovar woman known as the Shifter told the old graybeard. -

The Rings and Inner Moons of Uranus and Neptune: Recent Advances and Open Questions

Workshop on the Study of the Ice Giant Planets (2014) 2031.pdf THE RINGS AND INNER MOONS OF URANUS AND NEPTUNE: RECENT ADVANCES AND OPEN QUESTIONS. Mark R. Showalter1, 1SETI Institute (189 Bernardo Avenue, Mountain View, CA 94043, mshowal- [email protected]! ). The legacy of the Voyager mission still dominates patterns or “modes” seem to require ongoing perturba- our knowledge of the Uranus and Neptune ring-moon tions. It has long been hypothesized that numerous systems. That legacy includes the first clear images of small, unseen ring-moons are responsible, just as the nine narrow, dense Uranian rings and of the ring- Ophelia and Cordelia “shepherd” ring ε. However, arcs of Neptune. Voyager’s cameras also first revealed none of the missing moons were seen by Voyager, sug- eleven small, inner moons at Uranus and six at Nep- gesting that they must be quite small. Furthermore, the tune. The interplay between these rings and moons absence of moons in most of the gaps of Saturn’s rings, continues to raise fundamental dynamical questions; after a decade-long search by Cassini’s cameras, sug- each moon and each ring contributes a piece of the gests that confinement mechanisms other than shep- story of how these systems formed and evolved. herding might be viable. However, the details of these Nevertheless, Earth-based observations have pro- processes are unknown. vided and continue to provide invaluable new insights The outermost µ ring of Uranus shares its orbit into the behavior of these systems. Our most detailed with the tiny moon Mab. Keck and Hubble images knowledge of the rings’ geometry has come from spanning the visual and near-infrared reveal that this Earth-based stellar occultations; one fortuitous stellar ring is distinctly blue, unlike any other ring in the solar alignment revealed the moon Larissa well before Voy- system except one—Saturn’s E ring. -

The AVALON HILL

$2.50 The AVALON HILL July-August 1981 Volume 18, Number 2 3 A,--LJ;l.,,,, GE!Jco L!J~ &~~ 2~~ BRIDGE 8-1-2 4-2-3 4-4 4-6 10-4 5-4 This revision of a classic game you've long awaited is the culmination What's Inside . .. of five years of intensive research and playtest. The resuit. we 22" x 28" Fuli-color Mapboard of Ardennes Battlefield believe, will provide you pleasure for many years to come. Countersheet with 260 American, British and German Units For you historical buffs, BATTLE OF THE BULGE is the last word in countersheet of 117 Utility Markers accuracy. Official American and German documents, maps and Time Record Card actual battle reports (many very difficult to obtain) were consuited WI German Order of Appearance Card to ensure that both the order of battle and mapboard are correct Allied Order of Appearance Card to the last detail. Every fact was checked and double-checked. Rules Manual The reSUlt-you move the actual units over the same terrain that One Die their historical counterparts did in 1944. For the rest of you who are looking for a good, playable game, BATTLE OF THE BULGE is an operational recreation of the famous don't look any further. "BULGE" was designed to be FUN! This Ardennes battle of December, 1944-January, 1945. means a simple, streamlined playing system that gives you time to Each unit represents one of the regiments that actually make decisions instead of shuffling paper. The rules are short and participated (or might have participated) in the battle. -

Abstracts of the 50Th DDA Meeting (Boulder, CO)

Abstracts of the 50th DDA Meeting (Boulder, CO) American Astronomical Society June, 2019 100 — Dynamics on Asteroids break-up event around a Lagrange point. 100.01 — Simulations of a Synthetic Eurybates 100.02 — High-Fidelity Testing of Binary Asteroid Collisional Family Formation with Applications to 1999 KW4 Timothy Holt1; David Nesvorny2; Jonathan Horner1; Alex B. Davis1; Daniel Scheeres1 Rachel King1; Brad Carter1; Leigh Brookshaw1 1 Aerospace Engineering Sciences, University of Colorado Boulder 1 Centre for Astrophysics, University of Southern Queensland (Boulder, Colorado, United States) (Longmont, Colorado, United States) 2 Southwest Research Institute (Boulder, Connecticut, United The commonly accepted formation process for asym- States) metric binary asteroids is the spin up and eventual fission of rubble pile asteroids as proposed by Walsh, Of the six recognized collisional families in the Jo- Richardson and Michel (Walsh et al., Nature 2008) vian Trojan swarms, the Eurybates family is the and Scheeres (Scheeres, Icarus 2007). In this theory largest, with over 200 recognized members. Located a rubble pile asteroid is spun up by YORP until it around the Jovian L4 Lagrange point, librations of reaches a critical spin rate and experiences a mass the members make this family an interesting study shedding event forming a close, low-eccentricity in orbital dynamics. The Jovian Trojans are thought satellite. Further work by Jacobson and Scheeres to have been captured during an early period of in- used a planar, two-ellipsoid model to analyze the stability in the Solar system. The parent body of the evolutionary pathways of such a formation event family, 3548 Eurybates is one of the targets for the from the moment the bodies initially fission (Jacob- LUCY spacecraft, and our work will provide a dy- son and Scheeres, Icarus 2011). -

Megan Robinson

MEMOIR AS SIGNPOST: WRITING AT THE INTERSECTION OF ANCIENT FAITH AND CONTEMPORARY CULTURE Research and Analysis Supporting the Creation of BACK TO CANAAN: A PARABLE BY MEGAN J. ROBINSON SENIOR CREATIVE PROJECT submitted to the Individualized Studies Program in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree BACHELOR OF INDIVIDUALIZED STUDIES in RELIGIOUS AND CULTURAL STUDIES COMMITTEE MEMBERS: Dr. Catherine E. Saunders, Faculty Advisor Ms. Andrea B. Ruffner, Reader GEORGE MASON UNIVERSITY FAIRFAX, VIRGINIA DECEMBER 2006 ©2006 MEGAN J. ROBINSON ALL RIGHTS RESERVED PLEASE DIRECT ALL CORRESPONDENCE TO: [email protected] TABLE OF CONTENTS MEMOIR AS SIGNPOST Introduction 5 Rumors 8 Foreshadows: Evangelicalism as Clue Evangelical Publishing: A Blueprint for Faith Glimpses 14 Elements: Seeing a Story Elements: Reaching Into a Story Elements: Transformed By a Story Epiphanies 18 Theology: Foundation and Structure Wonder: The Open Door Narrative: Exploring the Cathedral Parable: Room to Grow Conclusion 28 Works Cited 30 Appendix A: Two Literary Models or Approaches 34 BACK TO CANAAN: A PARABLE Ur – Haran – Egypt 38 Barrenness Illumination Other Gods Altars and Plagues Long Day’s Journey Notes 62 INTRODUCTION Blueprints and cathedrals, at first glance, have little to do with creative writing. Yet, the word “cathedral” evokes spirituality, and thus provides an image that enables a discussion of how to approach writing on spiritual issues. In his analysis of the contemporary evangelical publishing industry, scholar Abram Van Engen explores how a writer should, or can, approach and produce literature from a Christian perspective. He proposes that, in the current market niche occupied by the evangelical publishing industry, audience and market demands have created a narrowly delineated “blueprint” model shaping a specific style and content of acceptable religious/spiritual literature, a model to which others less “mainstream” within the evangelical sub-culture react. -

Twixt Ocean and Pines : the Seaside Resort at Virginia Beach, 1880-1930 Jonathan Mark Souther

University of Richmond UR Scholarship Repository Master's Theses Student Research 5-1996 Twixt ocean and pines : the seaside resort at Virginia Beach, 1880-1930 Jonathan Mark Souther Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.richmond.edu/masters-theses Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Souther, Jonathan Mark, "Twixt ocean and pines : the seaside resort at Virginia Beach, 1880-1930" (1996). Master's Theses. Paper 1037. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Research at UR Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of UR Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TWIXT OCEAN AND PINES: THE SEASIDE RESORT AT VIRGINIA BEACH, 1880-1930 Jonathan Mark Souther Master of Arts University of Richmond, 1996 Robert C. Kenzer, Thesis Director This thesis descnbes the first fifty years of the creation of Virginia Beach as a seaside resort. It demonstrates the importance of railroads in promoting the resort and suggests that Virginia Beach followed a similar developmental pattern to that of other ocean resorts, particularly those ofthe famous New Jersey shore. Virginia Beach, plagued by infrastructure deficiencies and overshadowed by nearby Ocean View, did not stabilize until its promoters shifted their attention from wealthy northerners to Tidewater area residents. After experiencing difficulties exacerbated by the Panic of 1893, the burning of its premier hotel in 1907, and the hesitation bred by the Spanish American War and World War I, Virginia Beach enjoyed robust growth during the 1920s. While Virginia Beach is often perceived as a post- World War II community, this thesis argues that its prewar foundation was critical to its subsequent rise to become the largest city in Virginia. -

{DOWNLOAD} Cross

CROSS PDF, EPUB, EBOOK James Patterson | 464 pages | 29 Apr 2010 | Headline Publishing Group | 9780755349401 | English | London, United Kingdom Cross Pens for Discount & Sales | Last Chance to Buy | Cross The Christian cross , seen as a representation of the instrument of the crucifixion of Jesus , is the best-known symbol of Christianity. For a few centuries the emblem of Christ was a headless T-shaped Tau cross rather than a Latin cross. Elworthy considered this to originate from Pagan Druids who made Tau crosses of oak trees stripped of their branches, with two large limbs fastened at the top to represent a man's arm; this was Thau, or god. John Pearson, Bishop of Chester c. In which there was not only a straight and erected piece of Wood fixed in the Earth, but also a transverse Beam fastened unto that towards the top thereof". There are few extant examples of the cross in 2nd century Christian iconography. It has been argued that Christians were reluctant to use it as it depicts a purposely painful and gruesome method of public execution. The oldest extant depiction of the execution of Jesus in any medium seems to be the second-century or early third-century relief on a jasper gemstone meant for use as an amulet, which is now in the British Museum in London. It portrays a naked bearded man whose arms are tied at the wrists by short strips to the transom of a T-shaped cross. An inscription in Greek on the obverse contains an invocation of the redeeming crucified Christ. -

The Christian Mythology of CS Lewis and JRR Tolkien

Western Kentucky University TopSCHOLAR® Honors College Capstone Experience/Thesis Honors College at WKU Projects 2010 Roads to the Great Eucatastrophie: The hrC istian Mythology of C.S. Lewis and J.R.R. Tolkien Laura Anne Hess Western Kentucky University Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wku.edu/stu_hon_theses Part of the Philosophy Commons, and the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Hess, Laura Anne, "Roads to the Great Eucatastrophie: The hrC istian Mythology of C.S. Lewis and J.R.R. Tolkien" (2010). Honors College Capstone Experience/Thesis Projects. Paper 237. http://digitalcommons.wku.edu/stu_hon_theses/237 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by TopSCHOLAR®. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors College Capstone Experience/ Thesis Projects by an authorized administrator of TopSCHOLAR®. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Copyright by Laura Ann Hess 2010 ABSTRACT The purpose of this thesis is to analyze how C.S. Lewis and J.R.R. Tolkien created mythology that is fundamentally Christian but in vastly different ways. This task will be accomplished by examining the childhood and early adult life of both Lewis and Tolkien, as well as the effect their close friendship had on their writing, and by performing a detailed literary analysis of some of their mythological works. After an introduction, the second and third chapters will scrutinize the elements of their childhood and adolescence that shaped their later mythology. The next chapter will look at the importance of their Christian faith in their writing process, with special attention to Tolkien’s writing philosophy as explained in “On Fairy-Stories.” The fifth chapter analyzes the effect that Lewis and Tolkien’s friendship had on their writing, in conjunction with the effect of their literary club, the Inklings.