Megan Robinson

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Byzantine Liturgy and The

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Byzantine Liturgy and the Primary Chronicle A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Slavic Languages and Literatures by Sean Delaine Griffin 2014 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Byzantine Liturgy and the Primary Chronicle by Sean Delaine Griffin Doctor of Philosophy in Slavic Languages and Literatures University of California, Los Angeles, 2014 Professor Gail Lenhoff, Chair The monastic chroniclers of medieval Rus’ lived in a liturgical world. Morning, evening and night they prayed the “divine services” of the Byzantine Church, and this study is the first to examine how these rituals shaped the way they wrote and compiled the Povest’ vremennykh let (Primary Chronicle, ca. 12th century), the earliest surviving East Slavic historical record. My principal argument is that several foundational accounts of East Slavic history—including the tales of the baptism of Princess Ol’ga and her burial, Prince Vladimir’s conversion, the mass baptism of Rus’, and the martyrdom of Princes Boris and Gleb—have their source in the feasts of the liturgical year. The liturgy of the Eastern Church proclaimed a distinctively Byzantine myth of Christian origins: a sacred narrative about the conversion of the Roman Empire, the glorification of the emperor Constantine and empress Helen, and the victory of Christianity over paganism. In the decades following the conversion of Rus’, the chroniclers in Kiev learned these narratives from the church services and patterned their own tales of Christianization after them. The ii result was a myth of Christian origins for Rus’—a myth promulgated even today by the Russian Orthodox Church—that reproduced the myth of Christian origins for the Eastern Roman Empire articulated in the Byzantine rite. -

Christianity Unveiled; Being an Examination of the Principles and Effects of the Christian Religion

Christianity Unveiled; Being An Examination Of The Principles And Effects Of The Christian Religion by Paul Henri d’Holbach - 1761 [1819 translation by W. M. Johnson] CONTENTS. A LETTER from the Author to a Friend. CHAPTER I. - Of the necessity of an Inquiry respecting Religion, and the Obstacles which are met in pursuing this Inquiry. CHAPTER II. - Sketch of the History of the Jews. CHAPTER III. - Sketch of the History of the Christian Religion. CHAPTER IV. - Of the Christian Mythology, or the Ideas of God and his Conduct, given us by the Christian Religion. CHAPTER V. - Of Revelation. CHAPTER VI. - Of the Proofs of the Christian Religion, Miracles, Prophecies, and Martyrs. CHAPTER VII. - Of the Mysteries of the Christian Religion. CHAPTER VIII. - Mysteries and Dogmas of Christianity. CHAPTER IX. - Of the Rites and Ceremonies or Theurgy of the Christians. CHAPTER X. - Of the inspired Writings of the Christians. CHAPTER XI. - Of Christian Morality. CHAPTER XII. - Of the Christian Virtues. CHAPTER XIII. - Of the Practice and Duties of the Christian Religion. CHAPTER XIV. - Of the Political Effects of the Christian Religion. CHAPTER XV. - Of the Christian Church or Priesthood. CHAPTER XVI. - Conclusions. A LETTER FROM THE AUTHOR TO A FRIEND I RECEIVE, Sir, with gratitude, the remarks which you send me upon my work. If I am sensible to the praises you condescend to give it, I am too fond of truth to be displeased with the frankness with which you propose your objections. I find them sufficiently weighty to merit all my attention. He but ill deserves the title of philosopher, who has not the courage to hear his opinions contradicted. -

The George-Anne Student Media

Georgia Southern University Digital Commons@Georgia Southern The George-Anne Student Media 2-9-1995 The George-Anne Georgia Southern University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/george-anne Part of the Higher Education Commons Recommended Citation Georgia Southern University, "The George-Anne" (1995). The George-Anne. 1350. https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/george-anne/1350 This newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Media at Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. It has been accepted for inclusion in The George-Anne by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ■ ■:■ v.:'.:; :.:■::-:.:>:"■ fy- ■-;■,:-■:.. ->-■-■, ■,:■■■.■■;:■<:■>: ■-:■■■ ■ ■:■:■■<■;■■■■.■■/?, -.- - -■- GOLD EDITION Thursday, February 9,1995 Vol. 67, No. 47 The 67 years of journalism Read about how The George-Anne f got started back in ^1927, and how it Georgia Southern University's Official Student Newspaper ended up with one Statesboro, Georgia 30460 Founded 1927 .of the strangest names in the Pizza delivery robbed of money, food collegiate press... Please see "Q & A," page 3 the money ($218.20) and then ran." Attack in Stadium After the incident, the driver left Club brings up and noticed two policemen parked at BRIEFLY... Reuben and Ed's, so he drove into the questions of safety parking lot and informed the officers .. ::..,.:. ,. of the situation. They then rushed to AIDS now the leading killer for delivery drivers; the site of the crime in the police car, and then he called his manager to of young adults, experts say victim says he's report the incident. -

{DOWNLOAD} Cross

CROSS PDF, EPUB, EBOOK James Patterson | 464 pages | 29 Apr 2010 | Headline Publishing Group | 9780755349401 | English | London, United Kingdom Cross Pens for Discount & Sales | Last Chance to Buy | Cross The Christian cross , seen as a representation of the instrument of the crucifixion of Jesus , is the best-known symbol of Christianity. For a few centuries the emblem of Christ was a headless T-shaped Tau cross rather than a Latin cross. Elworthy considered this to originate from Pagan Druids who made Tau crosses of oak trees stripped of their branches, with two large limbs fastened at the top to represent a man's arm; this was Thau, or god. John Pearson, Bishop of Chester c. In which there was not only a straight and erected piece of Wood fixed in the Earth, but also a transverse Beam fastened unto that towards the top thereof". There are few extant examples of the cross in 2nd century Christian iconography. It has been argued that Christians were reluctant to use it as it depicts a purposely painful and gruesome method of public execution. The oldest extant depiction of the execution of Jesus in any medium seems to be the second-century or early third-century relief on a jasper gemstone meant for use as an amulet, which is now in the British Museum in London. It portrays a naked bearded man whose arms are tied at the wrists by short strips to the transom of a T-shaped cross. An inscription in Greek on the obverse contains an invocation of the redeeming crucified Christ. -

The Christian Mythology of CS Lewis and JRR Tolkien

Western Kentucky University TopSCHOLAR® Honors College Capstone Experience/Thesis Honors College at WKU Projects 2010 Roads to the Great Eucatastrophie: The hrC istian Mythology of C.S. Lewis and J.R.R. Tolkien Laura Anne Hess Western Kentucky University Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wku.edu/stu_hon_theses Part of the Philosophy Commons, and the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Hess, Laura Anne, "Roads to the Great Eucatastrophie: The hrC istian Mythology of C.S. Lewis and J.R.R. Tolkien" (2010). Honors College Capstone Experience/Thesis Projects. Paper 237. http://digitalcommons.wku.edu/stu_hon_theses/237 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by TopSCHOLAR®. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors College Capstone Experience/ Thesis Projects by an authorized administrator of TopSCHOLAR®. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Copyright by Laura Ann Hess 2010 ABSTRACT The purpose of this thesis is to analyze how C.S. Lewis and J.R.R. Tolkien created mythology that is fundamentally Christian but in vastly different ways. This task will be accomplished by examining the childhood and early adult life of both Lewis and Tolkien, as well as the effect their close friendship had on their writing, and by performing a detailed literary analysis of some of their mythological works. After an introduction, the second and third chapters will scrutinize the elements of their childhood and adolescence that shaped their later mythology. The next chapter will look at the importance of their Christian faith in their writing process, with special attention to Tolkien’s writing philosophy as explained in “On Fairy-Stories.” The fifth chapter analyzes the effect that Lewis and Tolkien’s friendship had on their writing, in conjunction with the effect of their literary club, the Inklings. -

Chanticleer| Vol 42, Issue 22

Jacksonville State University JSU Digital Commons Chanticleer Historical Newspapers 1995-03-09 Chanticleer | Vol 42, Issue 22 Jacksonville State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.jsu.edu/lib_ac_chanty Recommended Citation Jacksonville State University, "Chanticleer | Vol 42, Issue 22" (1995). Chanticleer. 1142. https://digitalcommons.jsu.edu/lib_ac_chanty/1142 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Historical Newspapers at JSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Chanticleer by an authorized administrator of JSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FEATURES: The two sides of Michael Franti, page 8 SPORTS: Rijle team places sixth in nation, page 14 1 I 1 Fz THE CHANTICLEER 4 v By Jamie Cole sented to the grandjury, only that an indict- Editor in Chief Case timeline ment was filed. "In this case, there's enough Heather under More than two months after an alleged Nov. 9, 1994: Rape is reported at evidence to go to trial," said Nichols. He rape was reported in Fitzpatrick Hall, a Fitzpatrick Hall. said he has "been in this business long criticism from grand jury indicted Daniel Brian Godwin, Jan. 13, 1995: Grand jury files indict- enough not to speculate" about anything 21, of Oxford, in connection with the al- ment charging Daniel Brian Godwin, 21, else. with first degree rape. deaf community leged crime. Wood said the case is still in its "infancy Jan. 30, 1995: Godwin is arrested and According to University Police Depart- released on bond. stages." A rather _laid-back Heather ment records, on Nov. -

Euromosaic III Touches Upon Vital Interests of Individuals and Their Living Conditions

Research Centre on Multilingualism at the KU Brussel E U R O M O S A I C III Presence of Regional and Minority Language Groups in the New Member States * * * * * C O N T E N T S Preface INTRODUCTION 1. Methodology 1.1 Data sources 5 1.2 Structure 5 1.3 Inclusion of languages 6 1.4 Working languages and translation 7 2. Regional or Minority Languages in the New Member States 2.1 Linguistic overview 8 2.2 Statistic and language use 9 2.3 Historical and geographical aspects 11 2.4 Statehood and beyond 12 INDIVIDUAL REPORTS Cyprus Country profile and languages 16 Bibliography 28 The Czech Republic Country profile 30 German 37 Polish 44 Romani 51 Slovak 59 Other languages 65 Bibliography 73 Estonia Country profile 79 Russian 88 Other languages 99 Bibliography 108 Hungary Country profile 111 Croatian 127 German 132 Romani 138 Romanian 143 Serbian 148 Slovak 152 Slovenian 156 Other languages 160 Bibliography 164 i Latvia Country profile 167 Belorussian 176 Polish 180 Russian 184 Ukrainian 189 Other languages 193 Bibliography 198 Lithuania Country profile 200 Polish 207 Russian 212 Other languages 217 Bibliography 225 Malta Country profile and linguistic situation 227 Poland Country profile 237 Belorussian 244 German 248 Kashubian 255 Lithuanian 261 Ruthenian/Lemkish 264 Ukrainian 268 Other languages 273 Bibliography 277 Slovakia Country profile 278 German 285 Hungarian 290 Romani 298 Other languages 305 Bibliography 313 Slovenia Country profile 316 Hungarian 323 Italian 328 Romani 334 Other languages 337 Bibliography 339 ii PREFACE i The European Union has been called the “modern Babel”, a statement that bears witness to the multitude of languages and cultures whose number has remarkably increased after the enlargement of the Union in May of 2004. -

Medieval Christian Mythology

Rachel Fulton Brown Department of History The University of Chicago MEDIEVAL CHRISTIAN MYTHOLOGY Winter 2019 Cambridge, Trinity College, MS R.16.2, “The Trinity Apocalypse” Heaven and hell, angels and demons, the Virgin Mary and the devil battling over the state of human souls, the world on the edge of apocalypse awaiting the coming of the Judge and the resurrection of the dead, the transubstantiation of bread and wine into body and blood, the great adventures of the saints. As Rudolf Bultmann put it in his summary of the “world picture” of the New Testament, “all of this is mythological talk,” arguably unnecessary for Christian theology. And yet, without its mythology, much of Christianity become incomprehensible as a religious or symbolic system. This course is intended as an introduction to the stories that medieval Christians told about God, his Mother, the angels, and the saints, along with the place of the sacraments and miracles in the world picture of the medieval church. Sources will range from Hugh of St. Victor’s summa on the sacraments, Guido of Monte Rochen’s handbook for parish priests and Hildegard of Bingen’s visionary Scivias to the Pseudo-Bonaventuran Meditations on the Life of Christ, Jacobus de Voragine’s Golden Legend, instructions for summoning angels and the York cycle of mystery plays. Emphasis will also be given to the way in which these stories were represented in art. HIST 21903 Medieval Christian Mythology 2 Winter 2019 BOOKS AVAILABLE FOR PURCHASE FROM THE SEMINARY CO-OP BOOKSTORE Anselm of Canterbury, The Prayers and Meditations, with the Proslogion, trans. -

Christian Mythology We Are Living in the Fullness of Time When We Are All Being Forced to Grow Up; the Bible Calls It Maturity Or Perfection

Piecemakers Country Store 1720 Adams Avenue Costa Mesa, CA 92626 (714) 641-3112 [email protected] Christian Mythology We are living in the fullness of time when we are all being forced to grow up; the Bible calls it maturity or perfection. There are not too many options left — we either grow up or perish. The human race is in the time of the harvest. If you claim to be a Christian you should know that the harvest is the end of the age (world), the coming of Christ. “For none of us liveth to himself, and no man dieth to himself. For whether we live or die, we are the Lord’s.” Romans 14:7 “Say not ye, ‘There are yet four months and then ever get our eyes and ears open to understand the cometh harvest?’ Behold, I say unto you, lift up your reason for God sending His Son into this grave eyes and look on the fields; for they are white already to called hell to rescue us? harvest.” Myth — when we die, we will go to heaven if we Let me give you an analogy so as to understand are good. Now for the truth, the reality. what the spiritual meaning of this verse is. Leprosy Romans 14:13 — “For the Kingdom of God is not starts out with red blotches and when it has run its meat and drink but righteousness, peace and joy in the course it turns white. Our entire civilization has leprosy Holy Ghost.” Only the new creation can experience that is white. -

Oman's Foreign Policy : Foundations and Practice

Florida International University FIU Digital Commons FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations University Graduate School 11-7-2005 Oman's foreign policy : foundations and practice Majid Al-Khalili Florida International University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/etd Part of the Other International and Area Studies Commons Recommended Citation Al-Khalili, Majid, "Oman's foreign policy : foundations and practice" (2005). FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 1045. https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/etd/1045 This work is brought to you for free and open access by the University Graduate School at FIU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of FIU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FLORIDA INTERNATIONAL UNIVERSITY Miami, Florida OMAN'S FOREIGN POLICY: FOUNDATIONS AND PRACTICE A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS by Majid Al-Khalili 2005 To: Interim Dean Mark Szuchman College of Arts and Sciences This dissertation, written by Majid Al-Khalili, and entitled Oman's Foreign Policy: Foundations and Practice, having been approved in respect to style and intellectual content, is referred to you for judgment. We have read this dissertation and recommend that it be approved. Dr. Nicholas Onuf Dr. Charles MacDonald Dr. Richard Olson Dr. 1Mohiaddin Mesbahi, Major Professor Date of Defense: November 7, 2005 The dissertation of Majid Al-Khalili is approved. Interim Dean Mark Szuchman C lege of Arts and Scenps Dean ouglas Wartzok University Graduate School Florida International University, 2005 ii @ Copyright 2005 by Majid Al-Khalili All rights reserved. -

Order Form Full

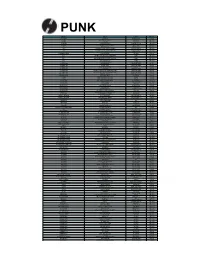

PUNK ARTIST TITLE LABEL RETAIL 100 DEMONS 100 DEMONS DEATHWISH INC RM90.00 4-SKINS A FISTFUL OF 4-SKINS RADIATION RM125.00 4-SKINS LOW LIFE RADIATION RM114.00 400 BLOWS SICKNESS & HEALTH ORIGINAL RECORD RM117.00 45 GRAVE SLEEP IN SAFETY (GREEN VINYL) REAL GONE RM142.00 999 DEATH IN SOHO PH RECORDS RM125.00 999 THE BIGGEST PRIZE IN SPORT (200 GR) DRASTIC PLASTIC RM121.00 999 THE BIGGEST PRIZE IN SPORT (GREEN) DRASTIC PLASTIC RM121.00 999 YOU US IT! COMBAT ROCK RM120.00 A WILHELM SCREAM PARTYCRASHER NO IDEA RM96.00 A.F.I. ANSWER THAT AND STAY FASHIONABLE NITRO RM119.00 A.F.I. BLACK SAILS IN THE SUNSET NITRO RM119.00 A.F.I. SHUT YOUR MOUTH AND OPEN YOUR EYES NITRO RM119.00 A.F.I. VERY PROUD OF YA NITRO RM119.00 ABEST ASYLUM (WHITE VINYL) THIS CHARMING MAN RM98.00 ACCUSED, THE ARCHIVE TAPES UNREST RECORDS RM108.00 ACCUSED, THE BAKED TAPES UNREST RECORDS RM98.00 ACCUSED, THE NASTY CUTS (1991-1993) UNREST RM98.00 ACCUSED, THE OH MARTHA! UNREST RECORDS RM93.00 ACCUSED, THE RETURN OF MARTHA SPLATTERHEAD (EARA UNREST RECORDS RM98.00 ACCUSED, THE RETURN OF MARTHA SPLATTERHEAD (SUBC UNREST RECORDS RM98.00 ACHTUNGS, THE WELCOME TO HELL GOING UNDEGROUND RM96.00 ACID BABY JESUS ACID BABY JESUS SLOVENLY RM94.00 ACIDEZ BEER DRINKERS SURVIVORS UNREST RM98.00 ACIDEZ DON'T ASK FOR PERMISSION UNREST RM98.00 ADICTS, THE AND IT WAS SO! (WHITE VINYL) NUCLEAR BLAST RM127.00 ADICTS, THE TWENTY SEVEN DAILY RECORDS RM120.00 ADOLESCENTS ADOLESCENTS FRONTIER RM97.00 ADOLESCENTS BRATS IN BATTALIONS NICKEL & DIME RM96.00 ADOLESCENTS LA VENDETTA FRONTIER RM95.00 ADOLESCENTS -

The Warrior Christ and His Gallows Tree

BACHELOR THESIS ENGLISH LANGUAGE AND CULTURE THE WARRIOR CHRIST AND HIS GALLOWS TREE The Dream of the Rood as an Example of Religious Syncretism MARIUS T. KOELINK SUPERVISED BY DRS. MONIQUE TANGELDER RADBOUD UNIVERSITY NIJMEGEN Abstract The Dream of the Rood is an Old English poem that contains both pagan and Christian elements. This mix has given rise to much debate on the nature of the pagan-Christian relationship in the Dream’s religiosity. The argument here is that Anglo-Saxon Christianity should be understood as a syncretic religion: a unique blend of different cultural and religious traditions that have merged into a seamless whole. Syncretism and inculturation are often used as blanket terms for interreligious phenomena, but Baer’s framework describes syncretism as a specific stage in the conversion process. Using syncretism as a framework, we see that the pagan elements in the Dream are projected onto Christian concepts and even used to strengthen Christian narratives. This is Christianity as experienced through a pagan heritage. There is no exhaustive theoretical framework of syncretism, but the Dream’s religiosity may serve as a case study to expand existing theories. Keywords: syncretism, The Dream of the Rood, Old English, poetry, Anglo-Saxon, Christianity, paganism, inculturation, religion Table of Contents Introduction 1 1. Searching for Anglo-Saxon Paganism 3 1.1 Vanished Paganism 3 1.2 Hidden Paganism 4 1.3 Lost Paganism 5 2. The Shape of Anglo-Saxon Christianity 7 2.1 Syncretism: An Introduction 7 2.2 Anglo-Saxon Christianity as a Syncretic Religion 11 2.3 Remaining Difficulties 15 3.