Our New Warner Bros. Theater!

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 Newcomer Among 5 Dealers Elected to CATA Board Seats

Volume 108, No. 12 June 27, 2011 Upcoming DealersEdge Webinars 1 newcomer among 5 dealers The Chicago Automobile Trade Association has estab- elected to CATA board seats lished a partnership with DealersEdge to provide high- quality training and informational Webinars that offer Results announced at Expo the content to CATA member dealers at a significantly An enthusiastic crowd of CATA board of directors discounted rate. dealers and their managers showed four incumbents and The rate for CATA members for the weekly presenta- showed up June 22 for the one newcomer won elec- tions is $149, half what is charged to users who do not 2nd annual CATA Dealer tion to three-year terms. Ed subscribe to DealersEdge. Webinars premiere on a near- Meeting & Expo, and they Burke, Dan Marks, Mike weekly basis. liked what they saw: 45 allied McGrath Jr. and Colin Even for dealers who hold an annual membership with members explaining their Wickstrom all won second DealersEdge, the new relationship with the CATA repre- products and services, and terms on the board. Bill sents a savings because DealersEdge offers its Webinars 11 educational seminars pre- Haggerty won for the first to its own members for $198. Regular annual member- sented during the day. time. ship fees are $397, and normal Webinar fees are $298 for At the Expo, results of A director may serve up non-DealersEdge members. this month’s balloting for the to three terms. Once purchased, DealersEdge Webinars and ac- companying PDF files can be downloaded and viewed Professionalism trumps price: study later—and repeatedly. -

Sentence Overturned for Centralia Gang Member Who Was Sent to Prison for 92 Years at Age 16 Shooting Sentence Shattered

Tenino Mayor Now the Subject of Investigation Following Alleged Sexual Activity in City Vehicle / Main 5 $1 Midweek Edition Thursday, Sept. 20, 2012 Reaching 110,000 Readers in Print and Online — www.chronline.com Cofee cups are seen in one of Ron Gaul’s cofee-stained paintings at the Morgan Art Centre in Toledo on Monday evening. See more in today’s Life: A&E. Pete Caster / [email protected] Two Local Women Charged Following Death of Intoxicated 16-Year-Old Chehalis Boy / Main 4 Sentence Overturned for Centralia Gang Member Who Was Sent to Prison for 92 Years at Age 16 Shooting Sentence Shattered Left: Guadalupe Solis- Diaz Jr., convicted for 2007 drive-by shooting in downtown Centralia DRIVE-BY Man make an appearance in a Lewis County courtroom after the Convicted for 2007 Washington Court of Appeals ‘‘Underwood failed to make ‘reasonable Drive-By Shooting to be ruled that his 92-year sentence efforts’ at advocating for his client during was unconstitutional and that his Resentenced legal representation during his sentencing ... Underwood did not to inform By Stephanie Schendel sentencing was “constitutionally deficient.” the court of a number of important factual [email protected] Guadalupe Solis-Diaz Jr. was and procedural considerations.’’ The former Centralia High 16 when he sprayed bullets along School student convicted for the the east side of Tower Avenue in Above: Michael Underwood, court 2007 drive-by shooting in down- according to unpublished opinion of the Washington State Court of Appeals appointed attorney for -

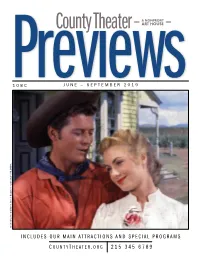

County Theater ART HOUSE

A NONPROFIT County Theater ART HOUSE Previews108C JUNE – SEPTEMBER 2019 Gordon MacRae and Shirley Jones in Rodgers & Hammerstein’s OKLAHOMA! & Hammerstein’s in Rodgers Gordon MacRae and Shirley Jones INCLUDES OUR MAIN ATTRACTIONS AND SPECIAL PROGRAMS C OUNTYT HEATER.ORG 215 345 6789 Welcome to the nonprofit County Theater The County Theater is a nonprofit, tax-exempt 501(c)(3) organization. Policies ADMISSION Children under 6 – Children under age 6 will not be admitted to our films or programs unless specifically indicated. General ............................................................$11.25 Late Arrivals – The Theater reserves the right to stop selling Members ...........................................................$6.75 tickets (and/or seating patrons) 10 minutes after a film has Seniors (62+) & Students ..................................$9.00 started. Matinees Outside Food and Drink – Patrons are not permitted to bring Mon, Tues, Thurs & Fri before 4:30 outside food and drink into the theater. Sat & Sun before 2:30 .....................................$9.00 Wed Early Matinee before 2:30 ........................$8.00 Accessibility & Hearing Assistance – The County Theater has wheelchair-accessible auditoriums and restrooms, and is Affiliated Theater Members* ...............................$6.75 equipped with hearing enhancement headsets and closed cap- You must present your membership card to obtain membership discounts. tion devices. (Please inquire at the concession stand.) The above ticket prices are subject to change. Parking Check our website for parking information. THANK YOU MEMBERS! Your membership is the foundation of the theater’s success. Without your membership support, we would not exist. Thank you for being a member. Contact us with your feedback How can you support or questions at 215 348 1878 x115 or email us at COUNTY THEATER the County Theater? MEMBER [email protected]. -

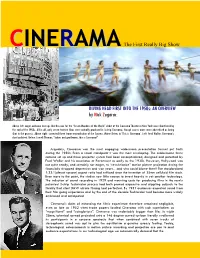

CINERAMA: the First Really Big Show

CCINEN RRAMAM : The First Really Big Show DIVING HEAD FIRST INTO THE 1950s:: AN OVERVIEW by Nick Zegarac Above left: eager audience line ups like this one for the “Seven Wonders of the World” debut at the Cinerama Theater in New York were short lived by the end of the 1950s. All in all, only seven feature films were actually produced in 3-strip Cinerama, though scores more were advertised as being shot in the process. Above right: corrected three frame reproduction of the Cypress Water Skiers in ‘This is Cinerama’. Left: Fred Waller, Cinerama’s chief architect. Below: Lowell Thomas; “ladies and gentlemen, this is Cinerama!” Arguably, Cinerama was the most engaging widescreen presentation format put forth during the 1950s. From a visual standpoint it was the most enveloping. The cumbersome three camera set up and three projector system had been conceptualized, designed and patented by Fred Waller and his associates at Paramount as early as the 1930s. However, Hollywood was not quite ready, and certainly not eager, to “revolutionize” motion picture projection during the financially strapped depression and war years…and who could blame them? The standardized 1:33:1(almost square) aspect ratio had sufficed since the invention of 35mm celluloid film stock. Even more to the point, the studios saw little reason to invest heavily in yet another technology. The induction of sound recording in 1929 and mounting costs for producing films in the newly patented 3-strip Technicolor process had both proved expensive and crippling adjuncts to the fluidity that silent B&W nitrate filming had perfected. -

The Search for Spectators: Vistavision and Technicolor in the Searchers Ruurd Dykstra the University of Western Ontario, [email protected]

Kino: The Western Undergraduate Journal of Film Studies Volume 1 | Issue 1 Article 1 2010 The Search for Spectators: VistaVision and Technicolor in The Searchers Ruurd Dykstra The University of Western Ontario, [email protected] Abstract With the growing popularity of television in the 1950s, theaters experienced a significant drop in audience attendance. Film studios explored new ways to attract audiences back to the theater by making film a more totalizing experience through new technologies such as wide screen and Technicolor. My paper gives a brief analysis of how these new technologies were received by film critics for the theatrical release of The Searchers ( John Ford, 1956) and how Warner Brothers incorporated these new technologies into promotional material of the film. Keywords Technicolor, The Searchers Recommended Citation Dykstra, Ruurd (2010) "The Search for Spectators: VistaVision and Technicolor in The Searchers," Kino: The Western Undergraduate Journal of Film Studies: Vol. 1 : Iss. 1 , Article 1. Dykstra: The Search for Spectators The Search for Spectators: VistaVision and Technicolor in The Searchers by Ruurd Dykstra In order to compete with the rising popularity of television, major Hollywood studios lured spectators into the theatres with technical innovations that television did not have - wider screens and brighter colors. Studios spent a small fortune developing new photographic techniques in order to compete with one another; this boom in photographic research resulted in a variety of different film formats being marketed by each studio, each claiming to be superior to the other. Filmmakers and critics alike valued these new formats because they allowed for a bright, clean, crisp image to be projected on a much larger screen - it enhanced the theatre going experience and brought about a re- appreciation for film’s visual aesthetics. -

The Films of Raoul Walsh, Part 1

Contents Screen Valentines: Great Movie Romances Screen Valentines: Great Movie Romances .......... 2 February 7–March 20 Vivien Leigh 100th ......................................... 4 30th Anniversary! 60th Anniversary! Burt Lancaster, Part 1 ...................................... 5 In time for Valentine's Day, and continuing into March, 70mm Print! JOURNEY TO ITALY [Viaggio In Italia] Play Ball! Hollywood and the AFI Silver offers a selection of great movie romances from STARMAN Fri, Feb 21, 7:15; Sat, Feb 22, 1:00; Wed, Feb 26, 9:15 across the decades, from 1930s screwball comedy to Fri, Mar 7, 9:45; Wed, Mar 12, 9:15 British couple Ingrid Bergman and George Sanders see their American Pastime ........................................... 8 the quirky rom-coms of today. This year’s lineup is bigger Jeff Bridges earned a Best Actor Oscar nomination for his portrayal of an Courtesy of RKO Pictures strained marriage come undone on a trip to Naples to dispose Action! The Films of Raoul Walsh, Part 1 .......... 10 than ever, including a trio of screwball comedies from alien from outer space who adopts the human form of Karen Allen’s recently of Sanders’ deceased uncle’s estate. But after threatening each Courtesy of Hollywood Pictures the magical movie year of 1939, celebrating their 75th Raoul Peck Retrospective ............................... 12 deceased husband in this beguiling, romantic sci-fi from genre innovator John other with divorce and separating for most of the trip, the two anniversaries this year. Carpenter. His starship shot down by U.S. air defenses over Wisconsin, are surprised to find their union rekindled and their spirits moved Festival of New Spanish Cinema .................... -

Summer Classic Film Series, Now in Its 43Rd Year

Austin has changed a lot over the past decade, but one tradition you can always count on is the Paramount Summer Classic Film Series, now in its 43rd year. We are presenting more than 110 films this summer, so look forward to more well-preserved film prints and dazzling digital restorations, romance and laughs and thrills and more. Escape the unbearable heat (another Austin tradition that isn’t going anywhere) and join us for a three-month-long celebration of the movies! Films screening at SUMMER CLASSIC FILM SERIES the Paramount will be marked with a , while films screening at Stateside will be marked with an . Presented by: A Weekend to Remember – Thurs, May 24 – Sun, May 27 We’re DEFINITELY Not in Kansas Anymore – Sun, June 3 We get the summer started with a weekend of characters and performers you’ll never forget These characters are stepping very far outside their comfort zones OPENING NIGHT FILM! Peter Sellers turns in not one but three incomparably Back to the Future 50TH ANNIVERSARY! hilarious performances, and director Stanley Kubrick Casablanca delivers pitch-dark comedy in this riotous satire of (1985, 116min/color, 35mm) Michael J. Fox, Planet of the Apes (1942, 102min/b&w, 35mm) Humphrey Bogart, Cold War paranoia that suggests we shouldn’t be as Christopher Lloyd, Lea Thompson, and Crispin (1968, 112min/color, 35mm) Charlton Heston, Ingrid Bergman, Paul Henreid, Claude Rains, Conrad worried about the bomb as we are about the inept Glover . Directed by Robert Zemeckis . Time travel- Roddy McDowell, and Kim Hunter. Directed by Veidt, Sydney Greenstreet, and Peter Lorre. -

Pittsburgh Vacant Lot T O O L K

PITTSBURGH VACANT LOT TOOLKIT Resource Guide VLTk December 2015 ABOUT THE toolkit The Vacant Lot Toolkit is a comprehensive overview of the goals, policies, processes, procedures, and guidelines for transforming vacant, blighted lots into temporary edible, flower, and rain gardens. Residents of the City of Pittsburgh can refer to this toolkit when thinking about creating a vacant lot project on City-owned land, and will find it useful throughout the process. The toolkit can also be a resource for projects on other public and privately owned land throughout the city. The City of Pittsburgh thanks you for your time, creativity, and stewardship to creating transformative projects in your ACKNOWLEDGMENTS neighborhoods. We look forward collaborating with you and VLTK Project Manager watching your projects grow. Josh Lippert, ASLA, Senior Environmental Planner Andrew Dash, AICP, Assistant Director For questions please refer to the Vacant Lot Toolkit Website: VLTK Program COORDINATOR www.pittsburghpa.gov/dcp/adoptalot Shelly Danko+Day, Open Space Specialist VLTK ADVISORY COMMITTEE City of Pittsburgh - Department of City Planning Raymond W. Gastil, AICP, Director **Please note that this toolkit is for new projects as well as City of Pittsburgh - Office of the Mayor existing projects that do not possess a current license, lease, Alex Pazuchanics right-of-entry, or waiver for City-owned property. Projects that exist without these will have to contact the Open Space Specialist City of Pittsburgh - Office of Sustainability and/or begin through the -

The Broken Ideals of Love and Family in Film Noir

1 Murder, Mugs, Molls, Marriage: The Broken Ideals of Love and Family in Film Noir Noir is a conversation rather than a single genre or style, though it does have a history, a complex of overlapping styles and typical plots, and more central directors and films. It is also a conversation about its more common philosophies, socio-economic and sexual concerns, and more expansively its social imaginaries. MacIntyre's three rival versions suggest the different ways noir can be studied. Tradition's approach explains better the failure of the other two, as will as their more limited successes. Something like the Thomist understanding of people pursuing perceived (but faulty) goods better explains the neo- Marxist (or other power/conflict) model and the self-construction model. Each is dependent upon the materials of an earlier tradition to advance its claims/interpretations. [Styles-studio versus on location; expressionist versus classical three-point lighting; low-key versus high lighting; whites/blacks versus grays; depth versus flat; theatrical versus pseudo-documentary; variety of felt threat levels—investigative; detective, procedural, etc.; basic trust in ability to restore safety and order versus various pictures of unopposable corruption to a more systemic nihilism; melodramatic vs. colder, more distant; dialogue—more or less wordy, more or less contrived, more or less realistic; musical score—how much it guides and dictates emotions; presence or absence of humor, sentiment, romance, healthy family life; narrator, narratival flashback; motives for criminality and violence-- socio- economic (expressed by criminal with or without irony), moral corruption (greed, desire for power), psychological pathology; cinematography—classical vs. -

Film Noir - Danger, Darkness and Dames

Online Course: Film Noir - Danger, Darkness and Dames WRITTEN BY CHRIS GARCIA Welcome to Film Noir: Danger, Darkness and Dames! This online course was written by Chris Garcia, an Austin American-Statesman Film Critic. The course was originally offered through Barnes & Noble's online education program and is now available on The Midnight Palace with permission. There are a few ways to get the most out of this class. We certainly recommend registering on our message boards if you aren't currently a member. This will allow you to discuss Film Noir with the other members; we have a category specifically dedicated to noir. Secondly, we also recommend that you purchase the following books. They will serve as a companion to the knowledge offered in this course. You can click each cover to purchase directly. Both of these books are very well written and provide incredible insight in to Film Noir, its many faces, themes and undertones. This course is structured in a way that makes it easy for students to follow along and pick up where they leave off. There are a total of FIVE lessons. Each lesson contains lectures, summaries and an assignment. Note: this course is not graded. The sole purpose is to give students a greater understanding of Dark City, or, Film Noir to the novice gumshoe. Having said that, the assignments are optional but highly recommended. The most important thing is to have fun! Enjoy the course! Jump to a Lesson: Lesson 1, Lesson 2, Lesson 3, Lesson 4, Lesson 5 Lesson 1: The Seeds of Film Noir, and What Noir Means Social and artistic developments forged a new genre. -

12 Big Names from World Cinema in Conversation with Marrakech Audiences

The 18th edition of the Marrakech International Film Festival runs from 29 November to 7 December 2019 12 BIG NAMES FROM WORLD CINEMA IN CONVERSATION WITH MARRAKECH AUDIENCES Rabat, 14 November 2019. The “Conversation with” section is one of the highlights of the Marrakech International Film Festival and returns during the 18th edition for some fascinating exchanges with some of those who create the magic of cinema around the world. As its name suggests, “Conversation with” is a forum for free-flowing discussion with some of the great names in international filmmaking. These sessions are free and open to all: industry professionals, journalists, and the general public. During last year’s festival, the launch of this new section was a huge hit with Moroccan and internatiojnal film lovers. More than 3,000 people attended seven conversations with some legendary names of the big screen, offering some intense moments with artists, who generously shared their vision and their cinematic techniques and delivered some dazzling demonstrations and fascinating anecdotes to an audience of cinephiles. After the success of the previous edition, the Festival is recreating the experience and expanding from seven to 11 conversations at this year’s event. Once again, some of the biggest names in international filmmaking have confirmed their participation at this major FIFM event. They include US director, actor, producer, and all-around legend Robert Redford, along with Academy Award-winning French actor Marion Cotillard. Multi-award-winning Palestinian director Elia Suleiman will also be in attendance, along with independent British producer Jeremy Thomas (The Last Emperor, Only Lovers Left Alive) and celebrated US actor Harvey Keitel, star of some of the biggest hits in cinema history including Thelma and Louise, The Piano, and Pulp Fiction. -

Generic Affinities, Posthumanisms and Science-Fictional Imaginings

GENERIC AFFINITIES, POSTHUMANISMS, SCIENCE-FICTIONAL IMAGININGS SPECULATIVE MATTER: GENERIC AFFINITIES, POSTHUMANISMS AND SCIENCE-FICTIONAL IMAGININGS By LAURA M. WIEBE, B.A., M.A. A Thesis Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy McMaster University © Copyright by Laura Wiebe, October 2012 McMaster University DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY (2012) Hamilton, Ontario (English and Cultural Studies) TITLE: Speculative Matter: Generic Affinities, Posthumanisms and Science-Fictional Imaginings AUTHOR: Laura Wiebe, B.A. (University of Waterloo), M.A. (Brock University) SUPERVISOR: Professor Anne Savage NUMBER OF PAGES: vi, 277 ii ABSTRACT Amidst the technoscientific ubiquity of the contemporary West (or global North), science fiction has come to seem the most current of genres, the narrative form best equipped to comment on and work through the social, political and ethical quandaries of rapid technoscientific development and the ways in which this development challenges conventional understandings of human identity and rationality. By this framing, the continuing popularity of stories about paranormal phenomena and supernatural entities – on mainstream television, or in print genres such as urban fantasy and paranormal romance – may seem to be a regressive reaction against the authority of and experience of living in technoscientific modernity. Nevertheless, the boundaries of science fiction, as with any genre, are relational rather than fixed, and critical engagements with Western/Northern technoscientific knowledge and practice and modern human identity and being may be found not just in science fiction “proper,” or in the scholarly field of science and technology studies, but also in the related genres of fantasy and paranormal romance.