Film Noir - Danger, Darkness and Dames

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

County Theater ART HOUSE

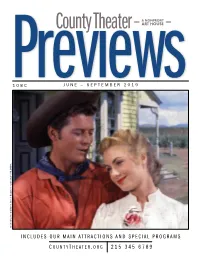

A NONPROFIT County Theater ART HOUSE Previews108C JUNE – SEPTEMBER 2019 Gordon MacRae and Shirley Jones in Rodgers & Hammerstein’s OKLAHOMA! & Hammerstein’s in Rodgers Gordon MacRae and Shirley Jones INCLUDES OUR MAIN ATTRACTIONS AND SPECIAL PROGRAMS C OUNTYT HEATER.ORG 215 345 6789 Welcome to the nonprofit County Theater The County Theater is a nonprofit, tax-exempt 501(c)(3) organization. Policies ADMISSION Children under 6 – Children under age 6 will not be admitted to our films or programs unless specifically indicated. General ............................................................$11.25 Late Arrivals – The Theater reserves the right to stop selling Members ...........................................................$6.75 tickets (and/or seating patrons) 10 minutes after a film has Seniors (62+) & Students ..................................$9.00 started. Matinees Outside Food and Drink – Patrons are not permitted to bring Mon, Tues, Thurs & Fri before 4:30 outside food and drink into the theater. Sat & Sun before 2:30 .....................................$9.00 Wed Early Matinee before 2:30 ........................$8.00 Accessibility & Hearing Assistance – The County Theater has wheelchair-accessible auditoriums and restrooms, and is Affiliated Theater Members* ...............................$6.75 equipped with hearing enhancement headsets and closed cap- You must present your membership card to obtain membership discounts. tion devices. (Please inquire at the concession stand.) The above ticket prices are subject to change. Parking Check our website for parking information. THANK YOU MEMBERS! Your membership is the foundation of the theater’s success. Without your membership support, we would not exist. Thank you for being a member. Contact us with your feedback How can you support or questions at 215 348 1878 x115 or email us at COUNTY THEATER the County Theater? MEMBER [email protected]. -

(#) Indicates That This Book Is Available As Ebook Or E

ADAMS, ELLERY 11.Indigo Dying 6. The Darling Dahlias and Books by the Bay Mystery 12.A Dilly of a Death the Eleven O'Clock 1. A Killer Plot* 13.Dead Man's Bones Lady 2. A Deadly Cliché 14.Bleeding Hearts 7. The Unlucky Clover 3. The Last Word 15.Spanish Dagger 8. The Poinsettia Puzzle 4. Written in Stone* 16.Nightshade 9. The Voodoo Lily 5. Poisoned Prose* 17.Wormwood 6. Lethal Letters* 18.Holly Blues ALEXANDER, TASHA 7. Writing All Wrongs* 19.Mourning Gloria Lady Emily Ashton Charmed Pie Shoppe 20.Cat's Claw 1. And Only to Deceive Mystery 21.Widow's Tears 2. A Poisoned Season* 1. Pies and Prejudice* 22.Death Come Quickly 3. A Fatal Waltz* 2. Peach Pies and Alibis* 23.Bittersweet 4. Tears of Pearl* 3. Pecan Pies and 24.Blood Orange 5. Dangerous to Know* Homicides* 25.The Mystery of the Lost 6. A Crimson Warning* 4. Lemon Pies and Little Cezanne* 7. Death in the Floating White Lies Cottage Tales of Beatrix City* 5. Breach of Crust* Potter 8. Behind the Shattered 1. The Tale of Hill Top Glass* ADDISON, ESME Farm 9. The Counterfeit Enchanted Bay Mystery 2. The Tale of Holly How Heiress* 1. A Spell of Trouble 3. The Tale of Cuckoo 10.The Adventuress Brow Wood 11.A Terrible Beauty ALAN, ISABELLA 4. The Tale of Hawthorn 12.Death in St. Petersburg Amish Quilt Shop House 1. Murder, Simply Stitched 5. The Tale of Briar Bank ALLAN, BARBARA 2. Murder, Plain and 6. The Tale of Applebeck Trash 'n' Treasures Simple Orchard Mystery 3. -

Wallace Stegner and the De-Mythologizing of the American West" (2004)

Digital Commons @ George Fox University Faculty Publications - Department of Professional Department of Professional Studies Studies 2004 Angling for Repose: Wallace Stegner and the De- Mythologizing of the American West Jennie A. Harrop George Fox University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/dps_fac Recommended Citation Harrop, Jennie A., "Angling for Repose: Wallace Stegner and the De-Mythologizing of the American West" (2004). Faculty Publications - Department of Professional Studies. Paper 5. http://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/dps_fac/5 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Professional Studies at Digital Commons @ George Fox University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications - Department of Professional Studies by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ George Fox University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ANGLING FOR REPOSE: WALLACE STEGNER AND THE DE-MYTHOLOGIZING OF THE AMERICAN WEST A Dissertation Presented to The Faculty of Arts and Humanities University of Denver In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy by Jennie A. Camp June 2004 Advisor: Dr. Margaret Earley Whitt Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. ©Copyright by Jennie A. Camp 2004 All Rights Reserved Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. GRADUATE STUDIES AT THE UNIVERSITY OF DENVER Upon the recommendation of the chairperson of the Department of English this dissertation is hereby accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Profess^inJ charge of dissertation Vice Provost for Graduate Studies / if H Date Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. -

12 Endangered Species Across the Globe Clinton, Chelsea 6.1 Did You Know That Blue Whales

6.0-7.0 Don't Let Them Clinton, Chelsea 6.1 Disappear: 12 Endangered Species Across the Globe Did you know that blue whales are the largest animals in the world? Or that sea otters wash their paws after every meal? The world is filled with millions of animal species, and all of them are unique and special. Many are on the path to extinction. In this book, Chelsea Clinton introduces young readers to a selection of endangered animals, sharing what makes them special, and also what threatens them. Taking readers through the course of a day, Don't Let Them Disappear talks about rhinos, tigers, whales, pandas and more, and provides helpful tips on what we all can do to help prevent these animals from disappearing from our world entirely. With warm and engaging art by Gianna Marino, this book is the perfect read for animal-lovers and anyone who cares about our planet. Ahsoka Johnston, E.K. 6.2 Fans have long wondered what happened to Ahsoka after she left the Jedi Order near the end of the Clone Wars, and before she re-appeared as the mysterious Rebel operative Fulcrum in Rebels. Finally, her story will begin to be told. Following her experiences with the Jedi and the devastation of Order 66, Ahsoka is unsure she can be part of a larger whole ever again. But her desire to fight the evils of the Empire and protect those who need it will lead her right to Bail Organa, and the Rebel Alliance.... Supernova Meyer, Marissa 6.3 All's fair in love and anarchy.. -

The Broken Ideals of Love and Family in Film Noir

1 Murder, Mugs, Molls, Marriage: The Broken Ideals of Love and Family in Film Noir Noir is a conversation rather than a single genre or style, though it does have a history, a complex of overlapping styles and typical plots, and more central directors and films. It is also a conversation about its more common philosophies, socio-economic and sexual concerns, and more expansively its social imaginaries. MacIntyre's three rival versions suggest the different ways noir can be studied. Tradition's approach explains better the failure of the other two, as will as their more limited successes. Something like the Thomist understanding of people pursuing perceived (but faulty) goods better explains the neo- Marxist (or other power/conflict) model and the self-construction model. Each is dependent upon the materials of an earlier tradition to advance its claims/interpretations. [Styles-studio versus on location; expressionist versus classical three-point lighting; low-key versus high lighting; whites/blacks versus grays; depth versus flat; theatrical versus pseudo-documentary; variety of felt threat levels—investigative; detective, procedural, etc.; basic trust in ability to restore safety and order versus various pictures of unopposable corruption to a more systemic nihilism; melodramatic vs. colder, more distant; dialogue—more or less wordy, more or less contrived, more or less realistic; musical score—how much it guides and dictates emotions; presence or absence of humor, sentiment, romance, healthy family life; narrator, narratival flashback; motives for criminality and violence-- socio- economic (expressed by criminal with or without irony), moral corruption (greed, desire for power), psychological pathology; cinematography—classical vs. -

1,000 Films to See Before You Die Published in the Guardian, June 2007

1,000 Films to See Before You Die Published in The Guardian, June 2007 http://film.guardian.co.uk/1000films/0,,2108487,00.html Ace in the Hole (Billy Wilder, 1951) Prescient satire on news manipulation, with Kirk Douglas as a washed-up hack making the most of a story that falls into his lap. One of Wilder's nastiest, most cynical efforts, who can say he wasn't actually soft-pedalling? He certainly thought it was the best film he'd ever made. Ace Ventura: Pet Detective (Tom Shadyac, 1994) A goofy detective turns town upside-down in search of a missing dolphin - any old plot would have done for oven-ready megastar Jim Carrey. A ski-jump hairdo, a zillion impersonations, making his bum "talk" - Ace Ventura showcases Jim Carrey's near-rapturous gifts for physical comedy long before he became encumbered by notions of serious acting. An Actor's Revenge (Kon Ichikawa, 1963) Prolific Japanese director Ichikawa scored a bulls-eye with this beautifully stylized potboiler that took its cues from traditional Kabuki theatre. It's all ballasted by a terrific double performance from Kazuo Hasegawa both as the female-impersonator who has sworn vengeance for the death of his parents, and the raucous thief who helps him. The Addiction (Abel Ferrara, 1995) Ferrara's comic-horror vision of modern urban vampires is an underrated masterpiece, full- throatedly bizarre and offensive. The vampire takes blood from the innocent mortal and creates another vampire, condemned to an eternity of addiction and despair. Ferrara's mob movie The Funeral, released at the same time, had a similar vision of violence and humiliation. -

Member Calendar MAR

Member Calendar MAR APR Mar–Apr 2019 “I never get over wondering at your prodigiousness,” MoMA founding director Alfred H. Barr Jr. mused admiringly to Lincoln Kirstein in 1945. Indeed, the extent of Kirstein’s influence on American culture in the 1930s and ’40s is hard to overstate. Best known for having cofounded, with the Russian choreographer George Balanchine, the School of American Ballet and the New York City Ballet, Kirstein was also a key figure in MoMA’s early history. Organizing exhibitions, writing catalogue essays, donating works to the Museum, and making acquisitions on its behalf, Kirstein championed a vision of modernism that favored figuration over abstraction and argued for an interdisciplinary marriage between the arts. Lincoln Kirstein’s Modern (Member Previews start March 13) invites you to rediscover rich areas of MoMA’s collection through the eyes of this impresario and tastemaker. The nearly 300 works on view include set and costume designs for the ballet; photography that explores American themes; sculpture that finds inspiration in folk art and classicism; finely rendered realist and magic-realist paintings; and the Latin American works that Kirstein purchased for the Museum in 1942. Some of these works might be old favorites, while others may represent new discoveries. The same is true for the Museum’s wide-ranging offerings this spring: the objects in The Value of Good Design may be things you use in your daily life; the paintings in Joan Miró: The Birth of the World may be familiar friends; while the recent acquisitions in New Order: Art and Technology in the Twenty-First Century have mostly not been seen before. -

Raoul Walsh to Attend Opening of Retrospective Tribute at Museum

The Museum of Modern Art jl west 53 Street, New York, N.Y. 10019 Tel. 956-6100 Cable: Modernart NO. 34 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE RAOUL WALSH TO ATTEND OPENING OF RETROSPECTIVE TRIBUTE AT MUSEUM Raoul Walsh, 87-year-old film director whose career in motion pictures spanned more than five decades, will come to New York for the opening of a three-month retrospective of his films beginning Thursday, April 18, at The Museum of Modern Art. In a rare public appearance Mr. Walsh will attend the 8 pm screening of "Gentleman Jim," his 1942 film in which Errol Flynn portrays the boxing champion James J. Corbett. One of the giants of American filmdom, Walsh has worked in all genres — Westerns, gangster films, war pictures, adventure films, musicals — and with many of Hollywood's greatest stars — Victor McLaglen, Gloria Swanson, Douglas Fair banks, Mae West, James Cagney, Humphrey Bogart, Marlene Dietrich and Edward G. Robinson, to name just a few. It is ultimately as a director of action pictures that Walsh is best known and a growing body of critical opinion places him in the front rank with directors like Ford, Hawks, Curtiz and Wellman. Richard Schickel has called him "one of the best action directors...we've ever had" and British film critic Julian Fox has written: "Raoul Walsh, more than any other legendary figure from Hollywood's golden past, has truly lived up to the early cinema's reputation for 'action all the way'...." Walsh's penchant for action is not surprising considering he began his career more than 60 years ago as a stunt-rider in early "westerns" filmed in the New Jersey hills. -

Film Soleil 28/9/05 3:35 Pm Page 2 Film Soleil 28/9/05 3:35 Pm Page 3

Film Soleil 28/9/05 3:35 pm Page 2 Film Soleil 28/9/05 3:35 pm Page 3 Film Soleil D.K. Holm www.pocketessentials.com This edition published in Great Britain 2005 by Pocket Essentials P.O.Box 394, Harpenden, Herts, AL5 1XJ, UK Distributed in the USA by Trafalgar Square Publishing P.O.Box 257, Howe Hill Road, North Pomfret, Vermont 05053 © D.K.Holm 2005 The right of D.K.Holm to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may beliable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages. The book is sold subject tothe condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out or otherwise circulated, without the publisher’s prior consent, in anyform, binding or cover other than in which it is published, and without similar condi-tions, including this condition being imposed on the subsequent publication. A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN 1–904048–50–1 2 4 6 8 10 9 7 5 3 1 Book typeset by Avocet Typeset, Chilton, Aylesbury, Bucks Printed and bound by Cox & Wyman, Reading, Berkshire Film Soleil 28/9/05 3:35 pm Page 5 Acknowledgements There is nothing -

Kiss Me Deadly by Alain Silver

Kiss Me Deadly By Alain Silver “A savage lyricism hurls us into a world in full decomposition, ruled by the dissolute and the cruel,” wrote Raymond Borde and Etienne Chaumeton about “Kiss Me Deadly” in their seminal study “Panorama du Film Noir Américain.” “To these violent and corrupt intrigues, Aldrich brings the most radical of solutions: nuclear apoca- lypse.” From the beginning, “Kiss Me Deadly” is a true sensory explosion. In the pre- credit sequence writer A.I. Bezzerides and producer/director Robert Aldrich introduce Christina (Cloris Leachman), a woman in a trench coat, who stumbles out of the pitch darkness onto a two-lane blacktop. While her breathing fills the soundtrack with am- plified, staccato gasps, blurred metallic shapes flash by without stopping. She posi- tions herself in the center of the roadway until oncoming headlights blind her with the harsh glare of their high beams. Brakes grab, tires scream across the asphalt, and a Jaguar spins off the highway in a swirl of dust. A close shot reveals Mike Hammer Robert Aldrich on the set of "Attack" in 1956 poses with the first (Ralph Meeker) behind the wheel: over the edition of "Panorama of American Film Noir." Photograph sounds of her panting and jazz on the car ra- courtesy Adell Aldrich. dio. The ignition grinds repeatedly as he tries to restart the engine. Finally, he snarls at her, satisfaction of the novel into a blacker, more sardon- “You almost wrecked my car! Well? Get in!” ic disdain for the world in general, the character be- comes a cipher for all the unsavory denizens of the For pulp novelist Mickey Spillane, Hammer's very film noir underworld. -

The Representation of Suicide in the Cinema

The Representation of Suicide in the Cinema John Saddington Submitted for the degree of PhD University of York Department of Sociology September 2010 Abstract This study examines representations of suicide in film. Based upon original research cataloguing 350 films it considers the ways in which suicide is portrayed and considers this in relation to gender conventions and cinematic traditions. The thesis is split into two sections, one which considers wider themes relating to suicide and film and a second which considers a number of exemplary films. Part I discusses the wider literature associated with scholarly approaches to the study of both suicide and gender. This is followed by quantitative analysis of the representation of suicide in films, allowing important trends to be identified, especially in relation to gender, changes over time and the method of suicide. In Part II, themes identified within the literature review and the data are explored further in relation to detailed exemplary film analyses. Six films have been chosen: Le Feu Fol/et (1963), Leaving Las Vegas (1995), The Killers (1946 and 1964), The Hustler (1961) and The Virgin Suicides (1999). These films are considered in three chapters which exemplify different ways that suicide is constructed. Chapters 4 and 5 explore the two categories that I have developed to differentiate the reasons why film characters commit suicide. These are Melancholic Suicide, which focuses on a fundamentally "internal" and often iII understood motivation, for example depression or long term illness; and Occasioned Suicide, where there is an "external" motivation for which the narrative provides apparently intelligible explanations, for instance where a character is seen to be in danger or to be suffering from feelings of guilt. -

Ben Kingsley Téa Leoni Luke Wilson T S O P K R O Y W

SCHW ÄRZER KANNEINEK OMÖDIE NICHTSEIN LUKE WILSON LUKE TÉA LEONI BEN KINGSLEY EINE KILLERKOMÖDIE VON JOHNDAHL VON EINE KILLERKOMÖDIE NEW YORK POST SCHWÄRZER KANN EINE KOMÖDIE NICHT SEIN NEW YORK POST FRANK BEN KINGSLEY LAUREL TÉA LEONI TOM LUKE WILSON BEN KINGSLEY TÉA LEONI LUKE WILSON O'LEARY DENNIS FARINA ROMAN PHILIP BAKER HALL YOU KILL ME DAVE BILL PULLMAN REGIE JOHN DAHL EINE RABENSCHWARZE KILLERKOMÖDIE DREHBUCH CHRISTOPHER MARKUS VON JOHN DAHL STEPHEN MCFEELY PRODUKTION CAROL BAUM AL CORLEY MIKE MARCUS USA 2007 EUGENE MUSSO BART ROSENBLATT 92 MINUTEN ZVI HOWARD ROSENMAN 2.35:1 KOPRODUKTION KIM OLSEN KAMERA JEFFREY JUR, A.S.R. DOLBY SRD SCHNITT SCOTT CHESTNUT AUSSTATTUNG JOHN DONDERTMAN KOSTÜME LINDA MADDEN MUSIK MARCELO ZARVOS SYNOPSIS Frank ist ein Gangster, ein Mafia-Killer und Auftragsmörder. Zynisch und gelassen sieht er das Töten als eine Art des Geldverdienens. Wären seine ausgeprägten Alkoholprobleme nicht, hätte er mit dem auf Disziplin gegründeten mafiösen Familiengeist keine Probleme. Doch leider verschläft er einen wichtigen Auftragsmord im Alkoholrausch, und das bisher in festem Familienbesitz stehende Geschäft mit Schneepflügen ist ernsthaft in Gefahr. Der Buffaloer Schnee- und Stadtlandschaft steht ein Machtwechsel ins Haus. Nachdem sein Onkel ein Machtwort gesprochen hat, wird Frank ohne viel Federlesen nach San Francisco verfrachtet, wo der zwielichtige Dave ihm Wohnung, Job und eine 12-Punkte-Therapie bei den anonymen Alkoholikern verschafft. Als frisch gebackener Leichen- kosmetiker in einem Bestattungsunternehmen darf er sich nun nicht mehr mit dem Töten, sondern nur noch mit den Toten beschäftigen. Inmitten einer kuriosen Schar von Freunden, Feinden, Auf- passern, lebensbejahenden Alkoholikern und untröstlichen Angehörigen wird Franks Leben völlig auf den Kopf gestellt.