The Rhetoric of Legal Crisis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

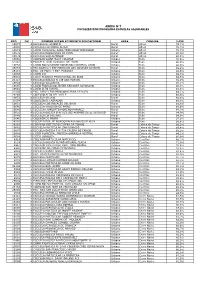

Porcentaje Alumnos Prioritarios 2019

Año Año RBD Nombre del establecimiento Dependencia Concentración proceso matrícula 1 LICEO POLITECNICO ARICA Municipal DAEM 2019 2018 62,41 2 PARVULARIO LAS ESPIGUITAS Municipal DAEM 2019 2018 30,26 3 ESC. PEDRO VICENTE GUTIERREZ TORRES Municipal DAEM 2019 2018 10,48 4 LICEO OCTAVIO PALMA PEREZ Municipal DAEM 2019 2018 53,07 5 JOVINA NARANJO FERNANDEZ Municipal DAEM 2019 2018 48,99 7 L. POLI. ANTONIO VARAS DE LA BARRA Municipal DAEM 2019 2018 71,17 8 COLEGIO INTEGRADO EDUARDO FREI MONTALVA Municipal DAEM 2019 2018 58,85 9 ESCUELA REPUBLICA DE ISRAEL Municipal DAEM 2019 2018 45,20 10 ESCUELA REPUBLICA DE FRANCIA Municipal DAEM 2019 2018 66,51 11 ESC. GRAL. PEDRO LAGOS MARCHANT Municipal DAEM 2019 2018 79,55 12 ESCUELA GRAL JOSE MIGUEL CARRERA Municipal DAEM 2019 2018 60,25 13 ESCUELA MANUEL RODRIGUEZ ERDOYZA Municipal DAEM 2019 2018 79,05 14 ESCUELA ROMULO J. PENA MATURANA Municipal DAEM 2019 2018 54,61 15 LICEO ARTISTICO DR. JUAN NOE CREVANI Municipal DAEM 2019 2018 50,61 16 ESCUELA REGIMIENTO RANCAGUA Municipal DAEM 2019 2018 62,47 17 ESCUELA SUBTTE. LUIS CRUZ MARTINEZ Municipal DAEM 2019 2018 69,50 18 ESC. COMTE. JUAN JOSE SAN MARTIN Municipal DAEM 2019 2018 76,13 19 ESC. HUMBERTO VALENZUELA GARCIA Municipal DAEM 2019 2018 73,20 20 ESCUELA TUCAPEL Municipal DAEM 2019 2018 73,84 21 ESCUELA CARLOS GUIRAO MASSIF Municipal DAEM 2019 2018 0,00 22 ESCUELA GABRIELA MISTRAL Municipal DAEM 2019 2018 68,54 25 COLEGIO CENTENARIO DE ARICA Municipal DAEM 2019 2018 72,62 26 ESCUELA REPUBLICA DE ARGENTINA Municipal DAEM 2019 2018 69,99 27 ESCUELA ESMERALDA Municipal DAEM 2019 2018 66,31 28 ESCUELA RICARDO SILVA ARRIAGADA Municipal DAEM 2019 2018 52,21 29 ESCUELA AMERICA Municipal DAEM 2019 2018 72,89 30 ESCUELA DR. -

Cinco Crónicas Políticas De Chile Y La Primera Mitad Del Siglo Xx (1920-1952)

CINCO CRÓNICAS POLÍTICAS DE CHILE Y LA PRIMERA MITAD DEL SIGLO XX (1920-1952) Memoria para optar al Título Profesional de Periodista Autores: Camilo Esteban Espinoza Mendoza Franco Elí Pardo Carvallo Profesor Guía: Eduardo Luis Santa Cruz Achurra Santiago, Chile, 2015 ÍNDICE Introducción pág. 3 Presentación pág. 7 El viaje de Recabarren pág. 20 Marmaduke Grove: Tiempos de militares pág. 54 El León todavía ruge: El caso Topaze pág. 77 El Ariostazo pág. 114 El duelo Allende-Rettig pág. 158 Conclusiones pág. 199 Bibliografía pág. 204 Evaluación pág. 212. 2 INTRODUCCIÓN Chile, particularmente durante la vigencia de su Constitución de 1925, para muchos politólogos gozó de una estabilidad “excepcional” dentro de Latinoamérica, emprendiendo un proyecto modernizador en base al respeto de su sistema institucional sin mayores sobresaltos en el camino. Sin embargo, aquella visión suele pasar por alto la serie de quiebres que rodearon la instalación de dicha Carta Magna, así como el surgimiento y llegada al poder de líderes populistas y autoritarios, militares reformistas y antiliberales, tecnócratas con proyectos apartidistas frustrados, e incluso el primer presidente marxista electo en el mundo. Lo cierto es que en un contexto de guerras mundiales y guerra fría, el país se embarcó en un intento democratizador que buscó romper con el oligárquico Chile decimonónico. La idea central pasaba por incluir en su sistema político - por lo menos en la forma- a una serie de sectores sociales hasta entonces absolutamente ajenos a la toma de decisiones. Sin embargo, no existió una única forma de afrontar el desafío, ni un camino llano que diese continuidad política al proceso. -

El Rol Del Estado Chileno En La Búsqueda Del Desarrollo Nacional (1920-1931)

Espacio Regional Volumen 2, Número 6, Osorno, 2009, pp. 119 - 132 EL ROL DEL ESTADO CHILENO EN LA BÚSQUEDA DEL DESARROLLO NACIONAL (1920-1931) Jorge Gaete Lagos [email protected] Universidad Andrés Bello Santiago, Chile RESUMEN El año 1924 representó un cambio profundo para la historia nacional, ya que se puso fin al régimen oligárquico-parlamentario, y se dio inicio a una etapa de transición que estuvo liderada por los militares, la cual se prolongó hasta 1932. Al integrarse a la escena política, ellos llevaron a cabo diversas reformas. Entre estas, podemos destacar que al Estado le otorgaron un mayor protagonismo en el país al asumir este la tarea de garantizar el “bien común” de la sociedad, lo cual se plasmó en la Constitución de 1925. Posteriormente, adquirió una función económica, ya que participó junto al sector privado y los sindicatos en los proyectos de desarrollo que comenzaron a gestarse. Por ende, este artículo estudiará el dinamismo que tuvo el Estado durante la década de 1920, y pondrá énfasis en la labor que asumió en el gobierno de Carlos Ibáñez del Campo (1927-1931). De esta forma, se mostrarán los antecedentes que tuvo el concepto de “Estado de bienestar”, el cual se concretó en 1939 con la llegada del Frente Popular. Palabras claves: Estado, eficiencia, proteccionismo, fomento, desarrollo económico, progreso ABSTRACT The year 1924 represented a profound change in national history as it ended the parliamentary- oligarchic regime, and began a transition that was led by the military, which lasted until 1932. On joining the political scene, they carried out various reforms. -

Rbd Dv Nombre Establecimiento

ANEXO N°7 FOCALIZACIÓN PROGRAMA ESCUELAS SALUDABLES RBD DV NOMBRE ESTABLECIMIENTO EDUCACIONAL AREA COMUNA %IVE 10877 4 ESCUELA EL ASIENTO Rural Alhué 74,7% 10880 4 ESCUELA HACIENDA ALHUE Rural Alhué 78,3% 10873 1 LICEO MUNICIPAL SARA TRONCOSO TRONCOSO Urbano Alhué 78,7% 10878 2 ESCUELA BARRANCAS DE PICHI Rural Alhué 80,0% 10879 0 ESCUELA SAN ALFONSO Rural Alhué 90,3% 10662 3 COLEGIO SAINT MARY COLLEGE Urbano Buin 76,5% 31081 6 ESCUELA SAN IGNACIO DE BUIN Urbano Buin 86,0% 10658 5 LICEO POLIVALENTE MODERNO CARDENAL CARO Urbano Buin 86,0% 26015 0 ESC.BASICA Y ESP.MARIA DE LOS ANGELES DE BUIN Rural Buin 88,2% 26111 4 ESC. DE PARV. Y ESP. PUKARAY Urbano Buin 88,6% 10638 0 LICEO 131 Urbano Buin 89,3% 25591 2 LICEO TECNICO PROFESIONAL DE BUIN Urbano Buin 89,5% 26117 3 ESCUELA BÁSICA N 149 SAN MARCEL Urbano Buin 89,9% 10643 7 ESCUELA VILLASECA Urbano Buin 90,1% 10645 3 LICEO FRANCISCO JAVIER KRUGGER ALVARADO Urbano Buin 90,8% 10641 0 LICEO ALTO JAHUEL Urbano Buin 91,8% 31036 0 ESC. PARV.Y ESP MUNDOPALABRA DE BUIN Urbano Buin 92,1% 26269 2 COLEGIO ALTO DEL VALLE Urbano Buin 92,5% 10652 6 ESCUELA VILUCO Rural Buin 92,6% 31054 9 COLEGIO EL LABRADOR Urbano Buin 93,6% 10651 8 ESCUELA LOS ROSALES DEL BAJO Rural Buin 93,8% 10646 1 ESCUELA VALDIVIA DE PAINE Urbano Buin 93,9% 10649 6 ESCUELA HUMBERTO MORENO RAMIREZ Rural Buin 94,3% 10656 9 ESCUELA BASICA G-N°813 LOS AROMOS DE EL RECURSO Rural Buin 94,9% 10648 8 ESCUELA LO SALINAS Rural Buin 94,9% 10640 2 COLEGIO DE MAIPO Urbano Buin 97,9% 26202 1 ESCUELA ESP. -

El Discurso Pedagógico De Pedro Aguirre Cerda. Ximena Recio

SERIE MONOGRAFIAS HISTORICAS Nº 10 EL DISCURSO PEDAGÓGICO DE PEDRO AGUIRRE CERDA Ximena M. Recio Palma INSTITUTO DE HISTORIA FACULTAD DE FILOSOFÍA Y EDUCACIÓN UNIVERSIDAD CATÓLICA DE VALPARAÍSO 1 2 Indice PROLOGO ................................................................................................................... I CAPITULO I PERFIL BIOGRÁFICO: EL POLÍTICO Y EL MAESTRO ANTES DE ASUMIR LA PRIMERA MAGISTRATURA......................................... 1 CAPITULO II LA EDUCACION EN EL IDEARIO DE AGUIRRE CERDA................................................................................................ 32 1. La Doctrina Radical como Paradigma de Base ................................................ 39 1.1 La crítica al Liberalismo ................................................................................... 41 1.2 El Positivismo Científico .................................................................................. 43 2. Educación y Democracia .................................................................................. 46 3. Educación y Economía ..................................................................................... 50 CAPITULO III LA «ESCUELA NUEVA» ........................................................................................... 57 1. El Magisterio ..................................................................................................... 60 1.1 Su elevación económico-social y la Libertad de Cátedra ................................ 60 1.2 Iniciativas de capacitación para -

The Chilean Miracle

Proefschrift DEF stramien 14-09-2005 09:35 Pagina 1 The Chilean miracle PATRIMONIALISM IN A MODERN FREE-MARKET DEMOCRACY Proefschrift DEF stramien 14-09-2005 09:35 Pagina 2 The Chilean miracle Promotor: PATRIMONIALISM IN A MODERN Prof. dr. P. Richards FREE-MARKET DEMOCRACY Hoogleraar Technologie en Agrarische Ontwikkeling Wageningen Universiteit Copromotor: Dr. C. Kay Associate Professor in Development Studies Institute of Social Studies, Den Haag LUCIAN PETER CHRISTOPH PEPPELENBOS Promotiecommissie: Prof. G. Mars Brunel University of London Proefschrift Prof. dr. S.W.F. Omta ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor Wageningen Universiteit op gezag van de rector magnificus van Wageningen Universiteit, Prof. dr. ir. J.D. van der Ploeg prof. dr. M. J. Kropff, Wageningen Universiteit in het openbaar te verdedigen op maandag 10 oktober 2005 Prof. dr. P. Silva des namiddags te vier uur in de Aula. Universiteit Leiden Dit onderzoek is uitgevoerd binnen de onderzoeksschool CERES Proefschrift DEF stramien 14-09-2005 09:35 Pagina 4 Preface The work that follows is an attempt to blend together cultural anthropology with managerial sciences in a study of Chilean agribusiness and political economy. It also blends together theory and practice, in a new account of Chilean institutional culture validated through real-life consultancy experiences. This venture required significant cooperation from various angles. I thank all persons in Chile who contributed to the fieldwork for this study. Special Peppelenbos, Lucian thanks go to local managers and technicians of “Tomatio” - a pseudonym for the firm The Chilean miracle. Patrimonialism that cooperated extensively and became key subject of this study. -

Discusiones Entre Honorables

FlAC S o TOMAS MOULIAN ECUADOR ISABEL TORRES DUJISIN r,~~\ .~... i'\ . :~~;.~ '.' .. ~ :;1 ';.-/ BIBLIOTECA DISCUSIONES ENTRE HONORABLES LAS CANDIDATURAS PRESIDENCIALES DE LA DERECHA ENTRE 1938 Y 1946 . FL~CSO •Biblioteca FLACSO Facultad Latinoamericana de Ciencias Sociales t'tSL CUT. 15'21 S ~,.~, IO'T!CA • n.AC!O ©FLACSO Inscripción Nº 68.645 ISBN 956-205-027 Diseño de Portada: Ximena Subercaseaux. Corrector y Supervisor: Leonel Roach. Composición y Diagramación: CRAN Ud Impresor: Imprenta Pucará 1a Edición de 1000 ejemplares, diciembre Impreso en Chile / Printed in Chile. INDICE AGRADECIMIENTOS 11 PROLOGO. Julio Subercaseaux 13 Capítulo Primero ORIGEN y SITUACION DE LA DERECHA HACIA 1933 21 I. La debilidad de la derecha en el sistema emergente de partidos " 21 1. La nueva estructura del sistema de partidos 23 "1' 2. La situación de la derecha 28. a) El fracaso de los intentos de modernización 28 b) La hegemonía del liberansmo económico 35 Capítulo Segundo LA CANDIDATURA DE GUSTAVO ROSS 43 .I. La coyuntura previa al proceso decisional de la derecha 43 1. Las elecciones parlamentarias de 1937 44 2. La renuncia de Gustavo Ross al Ministerio de Hacienda 53 3. El afianzamiento de las posiciones del Frente Popular en el radicalismo 56 4. El lanzamiento de la candidatura de Ibáñez 65 5. La creciente autonomización de la Juventud Conservadora. 68 II. El proceso decisional de la derecha 70 1. Los problemas en el Partido Conservador: la quina de la Juventud 71 2. Las luchas internas en el Partido Liberal 81 3. La candidatura Mane Gormaz 88 4. La Convención Presidencial de la derecha 92 5. -

The Structure of Political Conflict: Kinship Networks and Political Alignments in the Civil Wars of Nineteenth-Century Chile

THE STRUCTURE OF POLITICAL CONFLICT: KINSHIP NETWORKS AND POLITICAL ALIGNMENTS IN THE CIVIL WARS OF NINETEENTH-CENTURY CHILE Naim Bro This dissertation is submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Department of Sociology St Catharine’s College University of Cambridge July 2019 1 This thesis is the result of my own work and includes nothing which is the outcome of work done in collaboration except as declared in the Preface and specified in the text. It is not substantially the same as any that I have submitted, or, is being concurrently submitted for a degree or diploma or other qualification at the University of Cambridge or any other University or similar institution except as declared in the Preface and specified in the text. I further state that no substantial part of my thesis has already been submitted, or, is being concurrently submitted for any such degree, diploma or other qualification at the University of Cambridge or any other University or similar institution except as declared in the Preface and specified in the text. It does not exceed the prescribed word limit for the relevant Degree Committee. 2 THE STRUCTURE OF POLITICAL CONFLICT: KINSHIP NETWORKS AND POLITICAL ALIGNMENTS IN THE CIVIL WARS OF NINETEENTH-CENTURY CHILE Naim Bro Abstract Based on a novel database of kinship relations among the political elites of Chile in the nineteenth century, this thesis identifies the impact of family networks on the formation of political factions in the period 1828-1894. The sociological literature theorising the cleavages that divided elites during the initial phases of state formation has focused on three domains: 1) The conflict between an expanding state and the elites; 2) the conflict between different economic elites; and 3) the conflict between cultural and ideological blocs. -

Proyectos De Reformas De Iniciativa De Parlamentarios. a Las Constituciones Politicas De La Republica De Chile De 1925 Y 1980

Re vista de Derecho de la Universidad Cmólica de Valparaiso xvm ( 1997) PROYECTOS DE REFORMAS DE INICIA TIV A DE PARLAMENTARlOS, A LAS CONSTITUCIONES POLÍTICAS DE LA REP ÚBLICA DE CHILE DE 1925 Y 1980' SERGIO C A RR ASCO D . Universidad de Concepción l . PROPÓSITOS Apreciando que se trata de una malcria dc interesop oco estudiadal y de importancia. se plantea investigar: a) Si los proyectos de r¡;COlmas constitucion a le s~ de iniciativa de parlamentarios, son pocos o muchos. b) Las finalidades de tales proyectos. c) Si la siluaciún, en este aspct:lo. e·s similar o es di sr inra respecto de las Constitu ciones Polilicos de 1925 y 1980. d) Los resultados de los proyectos, en cuanto a su incorporación a los textos consti tucionales. 2. NÚMERO DE PROYECTOS 1\ 1 aspec to de si los proyectos en esnld io son pocos O muchos, es fácil concluir que fu eron -en nllmero- lIIud lOS. Relati vamente a la Consti tución Política de 1925. entre los años 1927 a 1969. se presentaron 83 proyectos: 57 (68,67%) de in ic.iativa de diputados y 26 (3 1,33%) de scnadorcs. Sólo entre 1950 a 1969 tueron 45. o sea. más de dos anuales en prome dio. Ilubo entonces una sostenida disposición de proponerse. frecuentemente, refor mas al texto constitucional con permanente tendencia al aumento. Si se considera e~ t c aspecto aproximadamente por décadas, el número de inicia ti vas -varias sobre dj versas materias- es: El presente trabajo deriva, principalmente, del Proyecto CONICYT-FONDECYf N' 193 0466. -

Cuadernos De Historia 49 Cuadernos De

CUADERNOS DE HISTORIA 49 CUADERNOS DE Santiago de Chile December of 2018 SUMMARY HISTORIA 49 Articles ISSN 0716-1832 versión impresa ISSN 0719-1243 versión electrónica The first stakes of John Thomas North’s nitrate kingdom. The origin of the myth .. 7-36 Sergio González Miranda Ways to lose the opportunity. Economies and Latin American independences, State of the art .................................................................................................................... 37-72 Antonio Santamaría García Japan´s Public Diplomacy and the Chilean Press during World War Two ............... 73-97 Pedro Iacobelli D. and Nicolás Camino V. On the origins of anti-peronism: the Democratic Union and the establishment of aguinaldo (1945-46) ............................................................................................. 99-123 Pablo Pizzorno Communist officials in the Government of González Videla, 1946-1947 ................ 125-173 Jorge Rojas Flores Dictatorship and Hegemonic Construction in a Regional Space: The CEMA Case at the ‘Greater Concepción’, 1973-1976 ................................................................... 175-193 Danny Monsálvez Araneda and Millaray Cárcamo Hermosilla Theological reason for the instrumental implementation of neoliberalism in Chile under the military civil dictatorship, 1973-1982 ....................................................... 195-220 Jorge Olguín Olate Documents DICIEMBRE 2018 People and landscapes of the chilean pacific ocean and southern peru, seen by a british corsair. Account -

MEMORI a DEL DECANO De La Facultad De Ciencias Jurídicas Y Sociales De La Universidad De Chile

MEMORI A DEL DECANO de la Facultad de Ciencias Jurídicas y Sociales de la Universidad de Chile 19 46- 1954 Separata DE LOS ANALES DE LA FACULTAD DE CIENCIAS JURIDICAS Y SOCIALES TERCERA EPOCA / YOL. I / N.°» 1-3 MEMO R I A I) E L D E C ANO de la Facultad de Ciencias Jurídicas v Sociales de la Universidad de Chile 1946-1954 Separata DE LOS ANA II-S DE LA FACULTAD DE CIENCIAS JURÍDICAS Y SOCIALES TERCERA EPOCA / VOL. I / N.«S 1-3 MEMORIA DEL DECANO DE LA FACULTAD DE CIENCIAS JURIDICAS Y SOCIALES DE LA UNIVERSIDAD DE CHILE 1946-1954 SUMARIO: I.—Servicios.—II. Labor general.—III. Funcionarios.—IV. Miembros Académicos.—V. Miembros Honorarios.—VI. Profesores Ordi- narios.—VII. Profesores Extraordinarios.—VIII. Escuelas de Servicio So- cial.—IX. Instituto y Escuela de Ciencias Políticas y Administrativas.— X. Alumnos de las Escuelas de Derecho.—XI. Reglamentos—XII. Planes y Programas de Estudios.—:XIII. Memorias de Licenciados.—XIV. Do- naciones.—XV. Premios.—XVI. Bibliotecas.—XVII. Anales.—XVIII. Construcción de la Escuela de Derecho de Valparaíso.—XIX. Construcción de bodegas en la Escuela de Derecho de Santiago.—XX. Editorial Jurídica de Chile.—XXI. Instituto Histórico y Bibliográfico de Ciencias Jurídicas y Sociales.—XXII. Presupuestos.—XXIII. Consejo Universitario.—XXIV. Establecimientos Particulares de Enseñanza Superior.—XXV. Conclusión. Honorable Facultad: En vísperas de terminar nuestro tercer período de Decano el 16 de abril de 1955, tenemos el honor de presentar a la H. Facultad esta Memoria que comprende prácticamente los tres períodos de tres años cada uno que hemos desempeñado dicho cargo. -

La Eterna Crisis Chilena 1924-1973. Ocaso De La Institucionalidad Demoliberal Entre Dos Pronunciamientos, Militar Y Cívico Militar

Revista Cruz de Sur, 2014, año IV, núm. 8 Págs. 87-149, ISSN: 2250-4478 La eterna crisis chilena 1924-1973. Ocaso de la institucionalidad demoliberal entre dos pronunciamientos, militar y cívico militar por Bernardino Bravo Lira I. Del Chile de ricos y pobres a la comunidad autoorganizada y la planificación global estatal desde arriba II. Autoorganización de la comunidad desde abajo y planificación global estatal desde arriba. III. Del Chile de ricos y pobres a la comunidad autoorganizada desde abajo. planificación global estatal desde arriba. IV. Del Estado interventor a la revolución desde arriba. V. El Chile Nuevo: global nonestado interventor. I. Introducción. Hasta principios del XX, bajo el régimen parlamentario, Chile se encontraba entre los países más estables del mundo, después de Inglaterra y Estados Unidos. Desde 1831 hasta 1924 los presidentes se sucedían regularmente, el congreso sesionaba sin interrupciones y las elecciones presidenciales, parlamentarias y municipales se verificaban en las fechas previstas. Esta fachada constitucional se acabó bruscamente al derrumbarse la república parlamentaria. La erosión venía de antes. Tras la revolución de 1891 el escenario había cambiado y cundía un difuso malestar y frustración. Desde luego, pasaron a segundo plano los dos temas de batalla en la lucha por desmontar la república ilustrada - confesionalidad del Estado y preeminencia presidencial-, y en 88 BERNARDINO BRAVO LIRA cambio, cobró inesperada urgencia el tercero: la protección de los desvalidos, que ahora se conoce como cuestión social. La igualdad legal impuesta desde arriba por el Estado, mediante la constitución y la codificación, a toda la población condena de hecho a las grandes mayorías a la indefensión, y da lugar a un Chile de ricos y pobres.