The Japanese Art of Listening an Ethnographic Investigation Into the Role of the Listener

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Images and Words. an Interdisciplinary Unit for Sixth-Grade Art and Language Arts Classes

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 391 771 SO 026 096 AUTHOR Lyons, Nancy Hai,:te; Ridley, Sarah TITLE Japan: Images and Words. An Interdisciplinary Unit for Sixth-Grade Art and Language Arts Classes. INSTITUTION Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC. Arthur M. Sackler Gallery. PUB DATE 94 NOTE 66p.; Color slides and prints not included in this document. AVAILABLE FROM Education Department, Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC 20560 ($24 plus $4.50 shipping and handling; packet includes six color slides and six color prints). PUB TYPE Guides Classroom Use Teaching Guides (For Teacher) (052) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC03 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Area Studies; *Art; Art Activities; Art Appreciation; *Art Education; Foreign Countries; Grade 6; *Interdisciplinary Approach; Intermediate Grades; *Japanese Culture; *Language Arts; Painting (Visual Arts) ;Visual_ Arts IDENTIFIERS Japan; *Japanese Art ABSTRACT This packet, written for teachers of sixth-grade art and language arts courses, is designed to inspire creative expression in words and images through an appreciation for Japanese art. The selection of paintings presented are from the Freer Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Institution. The interdisCiplinary approach, combines art and language arts. Lessons may be presented independently or together as a unit. Six images of art are provided as prints, slides, and in black and white photographic reproductions. Handouts for student use and a teacher's lesson guide also are included. Lessons begin with an anticipatory set designed to help students begin thinking about issues that will be discussed. A motivational activity, a development section, clusure, and follow-up activities are given for each lesson. Background information is provided at the end of each lesson. -

Title the NEET and Hikikomori Spectrum

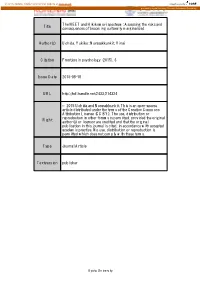

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Kyoto University Research Information Repository The NEET and Hikikomori spectrum: Assessing the risks and Title consequences of becoming culturally marginalized. Author(s) Uchida, Yukiko; Norasakkunkit, Vinai Citation Frontiers in psychology (2015), 6 Issue Date 2015-08-18 URL http://hdl.handle.net/2433/214324 © 2015 Uchida and Norasakkunkit. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original Right author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms. Type Journal Article Textversion publisher Kyoto University ORIGINAL RESEARCH published: 18 August 2015 doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01117 The NEET and Hikikomori spectrum: Assessing the risks and consequences of becoming culturally marginalized Yukiko Uchida 1* and Vinai Norasakkunkit 2 1 Kokoro Research Center, Kyoto University, Kyoto, Japan, 2 Department of Psychology, Gonzaga University, Spokane, WA, USA An increasing number of young people are becoming socially and economically marginalized in Japan under economic stagnation and pressures to be more globally competitive in a post-industrial economy. The phenomena of NEET/Hikikomori (occupational/social withdrawal) have attracted global attention in recent years. Though the behavioral symptoms of NEET and Hikikomori can be differentiated, some commonalities in psychological features can be found. Specifically, we believe that both NEET and Hikikomori show psychological tendencies that deviate from those Edited by: Tuukka Hannu Ilmari Toivonen, governed by mainstream cultural attitudes, values, and behaviors, with the difference University of London, UK between NEET and Hikikomori being largely a matter of degree. -

The Otaku Phenomenon : Pop Culture, Fandom, and Religiosity in Contemporary Japan

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository Electronic Theses and Dissertations 12-2017 The otaku phenomenon : pop culture, fandom, and religiosity in contemporary Japan. Kendra Nicole Sheehan University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/etd Part of the Comparative Methodologies and Theories Commons, Japanese Studies Commons, and the Other Religion Commons Recommended Citation Sheehan, Kendra Nicole, "The otaku phenomenon : pop culture, fandom, and religiosity in contemporary Japan." (2017). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 2850. https://doi.org/10.18297/etd/2850 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE OTAKU PHENOMENON: POP CULTURE, FANDOM, AND RELIGIOSITY IN CONTEMPORARY JAPAN By Kendra Nicole Sheehan B.A., University of Louisville, 2010 M.A., University of Louisville, 2012 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of the University of Louisville in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Humanities Department of Humanities University of Louisville Louisville, Kentucky December 2017 Copyright 2017 by Kendra Nicole Sheehan All rights reserved THE OTAKU PHENOMENON: POP CULTURE, FANDOM, AND RELIGIOSITY IN CONTEMPORARY JAPAN By Kendra Nicole Sheehan B.A., University of Louisville, 2010 M.A., University of Louisville, 2012 A Dissertation Approved on November 17, 2017 by the following Dissertation Committee: __________________________________ Dr. -

The Significance of Anime As a Novel Animation Form, Referencing Selected Works by Hayao Miyazaki, Satoshi Kon and Mamoru Oshii

The significance of anime as a novel animation form, referencing selected works by Hayao Miyazaki, Satoshi Kon and Mamoru Oshii Ywain Tomos submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Aberystwyth University Department of Theatre, Film and Television Studies, September 2013 DECLARATION This work has not previously been accepted in substance for any degree and is not being concurrently submitted in candidature for any degree. Signed………………………………………………………(candidate) Date …………………………………………………. STATEMENT 1 This dissertation is the result of my own independent work/investigation, except where otherwise stated. Other sources are acknowledged explicit references. A bibliography is appended. Signed………………………………………………………(candidate) Date …………………………………………………. STATEMENT 2 I hereby give consent for my dissertation, if accepted, to be available for photocopying and for inter-library loan, and for the title and summary to be made available to outside organisations. Signed………………………………………………………(candidate) Date …………………………………………………. 2 Acknowledgements I would to take this opportunity to sincerely thank my supervisors, Elin Haf Gruffydd Jones and Dr Dafydd Sills-Jones for all their help and support during this research study. Thanks are also due to my colleagues in the Department of Theatre, Film and Television Studies, Aberystwyth University for their friendship during my time at Aberystwyth. I would also like to thank Prof Josephine Berndt and Dr Sheuo Gan, Kyoto Seiko University, Kyoto for their valuable insights during my visit in 2011. In addition, I would like to express my thanks to the Coleg Cenedlaethol for the scholarship and the opportunity to develop research skills in the Welsh language. Finally I would like to thank my wife Tomoko for her support, patience and tolerance over the last four years – diolch o’r galon Tomoko, ありがとう 智子. -

Religion and Romanticism in Michael Ende's <I>The Neverending Story</I>

Volume 18 Number 1 Article 11 Fall 10-15-1991 Religion and Romanticism in Michael Ende's The Neverending Story Kath Filmer Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore Part of the Children's and Young Adult Literature Commons Recommended Citation Filmer, Kath (1991) "Religion and Romanticism in Michael Ende's The Neverending Story," Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature: Vol. 18 : No. 1 , Article 11. Available at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore/vol18/iss1/11 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Mythopoeic Society at SWOSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature by an authorized editor of SWOSU Digital Commons. An ADA compliant document is available upon request. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To join the Mythopoeic Society go to: http://www.mythsoc.org/join.htm Mythcon 51: A VIRTUAL “HALFLING” MYTHCON July 31 - August 1, 2021 (Saturday and Sunday) http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-51.htm Mythcon 52: The Mythic, the Fantastic, and the Alien Albuquerque, New Mexico; July 29 - August 1, 2022 http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-52.htm Abstract Deplores lack of critical attention to The Neverending Story, which she reads as “a profoundly religious text” which includes both spiritual and psychological growth. Additional Keywords Ende, Michael. The Neverending Story; Ende, Michael. The Neverending Story—Literary theory in; Ende, Michael. The Neverending Story—Religious aspects; Ende, Michael. -

No.766 (November Issue)

NBTHK SWORD JOURNAL ISSUE NUMBER 766 November, 2020 Meito Kansho: Examination of Important Swords Juyo Bijutsuhin, Important Cultural Property Type: Tachi Mei: Unji Length: 2 shaku 4 sun 4 bu 7 rin (74.15 cm) Sori: 9 bu 6 rin (2.9 cm) Motohaba: 9 bu 2 rin (2.8 cm) Sakihaba: 5 bu 9 rin (1.8 cm) Motokasane: 2 bu (0.6 cm) Sakikasane: 1 bu 2 rin (0.35 cm) Kissaki length: 8 bu 9 rin (2.7 cm) Nakago length: 6 sun 7 bu 3 rin (20.4 cm) Nakago sori: 7 rin (0.2 cm) Commentary This is a shinogi-zukuri tachi with an ihorimune. The width is standard, and the widths at the moto and saki are slightly different. There is a standard thickness, a large sori, and a chu-kissaki. The jigane has itame hada mixed with mokume and nagare hada, and the hada is barely visible. There are fine ji-nie, chikei, and jifu utsuri. The hamon is a wide suguha mixed with ko-gunome, ko-choji, and square features. There are frequent ashi and yo, and some places have saka-ashi. There is a tight nioiguchi with abundant ko-nie, and some kinsuji and sunagashi. The boshi on the omote is straight and there is a large round tip. The ura has a round tip, and there is a return. The nakago is suriage, and the nakago jiri is almost kiri, and the newer yasurime are sujichigai, and we cannot determine what style the old yasurime were. There are three mekugi-ana, On the omote, under the third mekugi-ana (the original mekugi-ana) there is a two kanji signature. -

Universitatea

10.2478/ewcp-2020-0011 Japan’s Food Culture – From Dango (Dumplings) to Tsukimi (Moon-Viewing) Burgers OANA-MARIA BÎRLEA Babeș-Bolyai University, Cluj-Napoca, Romania Abstract The purpose of this essay is to present how Japanese eating habits have changed in the context of globalization. We start from the premise that eating is not merely about meeting a basic need, but about creating a relationship with nature. It can be regarded as a ritual practice because it reveals a culture and its people’s beliefs, values and mind-sets. As Geert Hofstede et al. note, life in Japan is highly ritualized and there are a lot of ceremonies (192). Starting from the idea that food consumption is based on rituals too, we intend to explain the relationship between eating habits and lifestyle change in contemporary Japan. Considering that the Japanese diet is based on whole or minimally processed foods, we ask ourselves how Western food habits ended up being adopted and adapted so quickly in the Japanese society. With this purpose in mind, we intend to describe some of the most important festivals and celebrations in Japan, focusing on the relationship between special occasions and food. In other words, we aim to explain the cultural significance of food and eating and to see if and how these habits have changed in time. Keywords: Japan, Japanese culture, gastronomy, globalization, traditional eating, modern eating, food studies, eating habits, change, food-body-self relationship. Oana-Maria Bîrlea 55 Introduction The Japanese are known for their attention to detail, balance and desire to improve (Sarkar 134). -

Northern Gothic: Werner Haftmann's German

documenta studies #11 December 2020 NANNE BUURMAN Northern Gothic: Werner Haftmann’s German Lessons, or A Ghost (Hi)Story of Abstraction This essay by the documenta and exhibition scholar Nanne Buurman I See documenta: Curating the History of the Present, ed. by Nanne Buurman and Dorothee Richter, special traces the discursive tropes of nationalist art history in narratives on issue, OnCurating, no. 13 (June 2017). German pre- and postwar modernism. In Buurman’s “Ghost (Hi)Story of Abstraction” we encounter specters from the past who swept their connections to Nazism under the rug after 1945, but could not get rid of them. She shows how they haunt art history, theory, the German feuilleton, and even the critical German postwar literature. The editor of documenta studies, which we founded together with Carina Herring and Ina Wudtke in 2018, follows these ghosts from the history of German art and probes historical continuities across the decades flanking World War II, which she brings to the fore even where they still remain implicit. Buurman, who also coedited the volume documenta: Curating the History of the Present (2017),I thus uses her own contribution to documenta studies to call attention to the ongoing relevance of these historical issues for our contemporary practices. Let’s consider the Nazi exhibition of so-called Degenerate Art, presented in various German cities between 1937 and 1941, which is often regarded as documenta’s negative foil. To briefly recall the facts: The exhibition brought together more than 650 works by important artists of its time, with the sole aim of stigmatizing them and placing them in the context of the Nazis’ antisemitic racial ideology. -

November 2013 School Server Crashes, of Hard Knocks All Data Lost Concussion Dan- Principal Says Low Budget, Gers Haunt High High Turnover and Old Age School Football

The Poly Optimist John H. Francis Polytechnic High School Vol. XCIX, No. 4 Serving the Poly Community Since 1913 November 2013 School Server Crashes, of Hard Knocks All Data Lost Concussion dan- Principal says low budget, gers haunt high high turnover and old age school football. responsible for tech failure. By Danny Lopez By Yenifer Rodriguez of recovering the files, including Staff Writer Editor in Chief outsourcing. “There are companies that specialize in recovering data from High school football players Several Poly faculty members damaged or corrupted hard drives,” are nearly twice as likely to sustain lost years of data when a local stor- Schwagle said. “So I’m going to a concussion as college players, age drive, known as the “H” drive, according to a recent study by the failed two weeks ago. [ See Server, pg 6 ] Institute of Medicine. “We have no error codes, no Because a young athlete’s brain symptoms, nothing to tell us what is still developing, the effects of a went wrong,” said ROP teacher and Photo by Lirio Alberto concussion, or even many smaller computer expert Javier Rios. Giving Back hits over a season, can be far more SHOWTIME: Parrot freshman Priscilla Castaneda danced for the Clippers. The device was ten years old, ac- Two Parrots who got detrimental to a high school player cording to Rios. No back up system compared to head injury in a college was in place. help themselves are try- player. Poly Frosh Dances at “A lot of turnover in the technol- ing to return the favor. The study estimated that high ogy office and budgets cuts of 20% school football players suffered 11.2 school wide in the last few years By Christine Maralit concussions for every 10,000 games Staples Half-time Show have affected our ability to man- Staff Writer and practices. -

Their Majesties the Emperor and Empress and the Imperial Family

Their Majesties the Emperor and Empress and the Imperial Family Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan January 2021 1 【Contents】 1. The Emperor and the Imperial Family 2. Personal Histories 3. Ceremonies of the Accession to the Throne (From Heisei to Reiwa) 4. Activities of Their Majesties the Emperor and Empress 5. Imperial Palace ※ NB: This material provides basic information about the Imperial Family, which helps foreign readers understand the role and the activities of the Imperial Family of Japan. Cover Photo: Nijubashi Bridges spanning the moat of the Imperial Palace, Tokyo 2 1. The Emperor and the Imperial Family ⃝ The Emperor 【 Position】 1 The Emperor is the symbol of the State and of the unity of the people, deriving his position from the will of the people with whom resides sovereign power (the Constitution of Japan, Article 1). 2 The Imperial Throne is dynastic and succeeded to in accordance with the Imperial House Law passed by the Diet (Constitution, Article 2). 【 Powers】 1 The Emperor performs only such acts in matters of state as are provided for in the Constitution, and has no powers related to government (Constitution, Article 4(1)). 2 The Emperor's acts in matters of State (Constitution, Articles 6, Article 7, and Article 4(2)). (1) Appointment of the Prime Minister as designated by the Diet (2) Appointment of the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court as designated by the Cabinet (3) Promulgation of amendments of the Constitution, laws, cabinet orders, and treaties (4) Convocation of the Diet (5) Dissolution of the House -

Event Report: Global Launching of the United Nations Decade On

EVENT REPORT 17–19 DECEMBER 2011 KANAZAWA, ISHIKAWA, JAPAN Global Launching of the United Nations Decade on Biodiversity 2011–2020 Prepared by the United Nations University Institute for Sustainability and Peace May 2012 Prepared by the United Nations University Institute for Sustainability and Peace Participants observe a traditional community agricultural site at Shiroyonesenmaida Rice Terraces, Noto. Contents EVENT REPORT 17–19 DECEMBER 2011 KANAZAWA, ISHIKAWA, JAPAN Global Launching of the United Nations Decade on Biodiversity 2011–2020 3 Executive Summary 4 Background Prepared by the United Nations University Institute for Sustainability and Peace nt Programme 5 Eve ?? March 2012 Prepared by the United Nations University Institute for Sustainability and Peace Event Report Global Launching of the 10 Three-day Event Report United Nations Decade on Biodiversity 10 Day 1 (17 December 2011) 2011–2020 10 Event 1: Commemorative Ceremony 17 Event 2: Reception 18 Day 2 (18 December 2011) 18 Event 1: International Workshop: Acknowledgements National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plans The United Nations University would like to express our gratitude to the 28 Workshop Participants Ministry of the Environment Japan and 29 Event 2: Commemorative Forum the Secretariat for the Convention on Biological Diversity for their generous support in the organization of this event. 30 Day 3 (19 December 2011) We would also like to acknowledge 31 Excursion 1: Noto the contributions of the participants 31 Excursion 2: Kaga by their attendance, to which we are grateful. By providing us with their 31 Excursion 3: Kanazawa expertise and experience it has not 31 Excursion 4: Kanazawa only made the event a success, but has demonstrated the global commitment to conserve biodiversity. -

A Thesis Entitled Yoshimoto Taka'aki, Communal Illusion, and The

A Thesis entitled Yoshimoto Taka’aki, Communal Illusion, and the Japanese New Left by Manuel Yang Submitted as partial fulfillment for requirements for The Master of Arts Degree in History ________________________ Adviser: Dr. William D. Hoover ________________________ Adviser: Dr. Peter Linebaugh ________________________ Dr. Alfred Cave ________________________ Graduate School The University of Toledo (July 2005) ACKNOWLEDGMENTS It is customary in a note of acknowledgments to make the usual mea culpa concerning the impossibility of enumerating all the people to whom the author has incurred a debt in writing his or her work, but, in my case, this is far truer than I can ever say. This note is, therefore, a necessarily abbreviated one and I ask for a small jubilee, cancellation of all debts, from those that I fail to mention here due to lack of space and invidiously ungrateful forgetfulness. Prof. Peter Linebaugh, sage of the trans-Atlantic commons, who, as peerless mentor and comrade, kept me on the straight and narrow with infinite "grandmotherly kindness" when my temptation was always to break the keisaku and wander off into apostate digressions; conversations with him never failed to recharge the fiery voltage of necessity and desire of historical imagination in my thinking. The generously patient and supportive free rein that Prof. William D. Hoover, the co-chair of my thesis committee, gave me in exploring subjects and interests of my liking at my own preferred pace were nothing short of an ideal that all academic apprentices would find exceedingly enviable; his meticulous comments have time and again mercifully saved me from committing a number of elementary factual and stylistic errors.