Jewish Baths of Siracusa

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Presentazione Standard Di Powerpoint

CEPR European Conference on Household Finance 2018 WELCOME GUIDE Ortygia Business School Via Roma, 124 96100 Siracusa +39 0931 69510 www.ortygiabs.org [email protected] The Conference Venue Ortygia Business School Via Roma, 124 96100 Siracusa +39 0931 69510 www.ortygiabs.org [email protected] Hotel Accommodation Grand Hotel Ortigia https://www.grandhotelortigia.it/ Des Etrangers http://www.desetrangers.com/ Ortygia Business School Via Roma, 124 96100 Siracusa +39 0931 69510 www.ortygiabs.org [email protected] Hotel Accommodation Palazzo Gilistro https://www.palazzogilistro.it/ Hotel Gutkowski http://www.guthotel.it/ Ortygia Business School Via Roma, 124 96100 Siracusa +39 0931 69510 www.ortygiabs.org [email protected] Transport Catania Airport Fontanarossa http://www.aeroporto.catania.it/ Train Station Siracusa https://goo.gl/6AK4Ee Ortygia Business School Via Roma, 124 96100 Siracusa +39 0931 69510 www.ortygiabs.org [email protected] 1 – The Greek theatre Impressive, solemn, intriguing, with stunning views. It may happen that, while sitting on the big stone steps , you hear the voices of the great Greek heroes, Agamemnon, Medea or Oedipus, even if there are no actors on the stage …this is such an evocative place! It keeps evidences of several historic periods, from the prehistoric ages to Late Antiquity and the Byzantine era. The Greek Theatre is one of the biggest in the world, entirely carved into the rock. In ancient times it was used for plays and popular assemblies, today it is the place where the Greek tragedies live again through the Series of Classical Performances that take place every year thanks to the INDA, National Institute of Ancient Drama. -

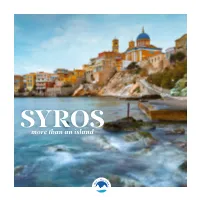

More Than an Island 2 MORE THAN an ISLAND

SYROS more than an island 2 MORE THAN AN ISLAND... ΧΧΧ TABLE OF CONTENTS Discovering Syros .................................... 4 Introduction From myth to history ............................. 6 History The two Doctrines .................................. 8 Religion will never forget the dreamy snowy white color, which got in my eyes when I landed in Syros at Two equal tribes this fertile land I dawn. Steamers always arrive at dawn, at this divide, where two fair cities rise all-white swan of the Aegean Sea that is as if it is with equal pride ...................................... 10 sleeping on the foams, with which the rainmaker is sprinkling. Kaikias, the northeast wind; on her Cities and countryside eastern bare side, the renowned Vaporia, which is Economy of Syros .................................... 14 always anchored beyond St. Nicholas, a fine piece of a crossway, and immortal Nisaki downtown, the Tourism, agricultural production, swan’s proud neck, with Vafiadakis’s buildings, and crafts and traditional shipbuilding the solid towers of the Customs Office, where the waves alive, as if they are hopping, laughing, run- Authentic beauty ..................................... 16 ning, chuckling, hunting, fighting, kissing, being Beaches, flora and fauna, habitats, baptized, swimming, brides white like foam. climate and geotourism At such time and in this weather, I landed on my dream island. I don’t know why some mysteries lie Culture, twelve months a year .......... 18 in man’s heart, always remaining dark and unex- Architecture, tradition, theatre, literature, plained. I loved Syra, ever since I first saw it. I loved music, visual arts and gastronomy her and wanted to see her again. I wanted to gaze at her once more. -

Elia Samuele Artom Go to Personal File

Intellectuals Displaced from Fascist Italy © Firenze University Press 2019 Elia Samuele Artom Go to Personal File «When, in 1938, I delivered my last lecture at this University, as a libero docente Link to other connected Lives on the [lecturer with official certification to teach at the university] of Hebrew language move: and literature I would not have believed...»: in this way, Elia Samuele Artom opened Emanuele Menachem the commemoration of his brother-in-law, Umberto Cassuto, on 28 May 1952 in Artom 1 Enzo Bonaventura Florence, where he was just passing through . Umberto Cassuto The change that so many lives, like his own, had to undergo as a result of anti- Anna Di Gioacchino Cassuto Jewish laws was radical. Artom embarked for Mandatory Palestine in September Enrico Fermi Kalman Friedman 1939, with his younger son Ruben. Upon arrival he found a land that was not simple, Dante Lattes whose ‘promise’ – at the center of the sources of tradition so dear to him – proved Alfonso Pacifici David Prato to be far more elusive than certain rhetoric would lead one to believe. Giulio Racah His youth and studies Elia Samuele Artom was born in Turin on 15 June 1887 to Emanuele Salvador (8 December 1840 – 17 June 1909), a post office worker from Asti, and Giuseppina Levi (27 August 1849 – 1 December 1924), a kindergarten teacher from Carmagnola2. He immediately showed a unique aptitude for learning: after being privately educated,3 he obtained «the high school honors diploma» in 1904; he graduated in literature «with full marks and honors» from the Facoltà di Filosofia e 1 Elia Samuele Artom, Umberto Cassuto, «La Rassegna mensile di Israel», 18, 1952, p. -

Catalogue of Manuscripts in the Roth Collection’, Contributed by Cecil Roth Himself to the Alexander Marx Jubilee Volume (New York, 1950), Where It Forms Pp

Handlist 164 LEEDS UNIVERSITY LIBRARY Provisional handlist of manuscripts in the Roth Collection Introduction Dr Cecil Roth (1899-1970), the Jewish historian, was born on 5 March 1899 in Dalston, London, the youngest of the four sons of Joseph and Etty Roth. Educated at the City of London School, he saw active service in France in 1918 and then read history at Merton College, Oxford, obtaining a first class degree in modern history in 1922, and a DPhil in 1924; his thesis was published in 1925 as The Last Florentine Republic. In 1928 he married Irene Rosalind Davis. They had no children. Roth soon turned to Jewish studies, his interest from childhood, when he had a traditional religious education and learned Hebrew from the Cairo Genizah scholar Jacob Mann. He supported himself by freelance writing until in 1939 he received a specially created readership in post-biblical Jewish studies at the University of Oxford, where he taught until his retirement in 1964. He then settled in Israel and divided his last years between New York, where he was visiting professor at Queens’ College in City University and Stern College, and Jerusalem. He died in Jerusalem on 21 June 1970. Roth’s literary output was immense, ranging from definitive histories of the Jews both globally and in several particular countries, to bibliographical works, studies of painting, scholarly research, notably on the Dead Sea scrolls, and biographical works. But his crowning achievement was the editorship of the Encyclopaedia Judaica, which appeared in the year of his death. Throughout his life Roth collected both books and manuscripts, and art objects. -

An Italian Tune in the Synagogue: an Unexplored Contrafactum by Leon Modena∗

Kedem G OLDEN AN ITALIAN TUNE IN THE SYNAGOGUE: AN UNEXPLORED CONTRAFACTUM BY LEON MODENA∗ ABSTRACT Leon Modena, one of the celebrated personalities of Italian Jewry in the early modern period, is known for his extensive, life-long involvement with music in its various theoretical and practical aspects. The article presents additional evidence that has gone unnoticed in previous studies of Modena’s musical endeavors: his adaption of a polyphonic, secular Italian melody, for the singing of a liturgical hymn. After identifying the melody and suggesting a possible date for the compo- sition of the Hebrew text, the article proceeds to discuss it in a broader context of the Jewish musical culture at the turn of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, in particular contemporary Jewish views to the use of “foreign” melodies in the syna- gogue. The article concludes with an attempt to situate it as part of Modena’s thought of art music. RÉSUMÉ Léon Modène, une des personnalités célèbres du judaïsme italien du début de la période moderne, est connu pour s’être impliqué de près dans le monde de la musique et ses divers aspects, aussi bien théoriques que pratiques. Le présent article présente un exemple supplémentaire de cette implication, passé inaperçu dans les études antérieures: l’adaptation par Modène d’une mélodie polyphonique profane italienne en un hymne liturgique. Après avoir identifié la mélodie et suggéré la date éventuelle de la composition du texte hébreu, l’article analyse cet hymne dans le contexte plus large de la culture musicale juive au tournant des XVIe et XVIIe siècles, notamment en tenant compte des opinions juives contemporaines sur l’usage de chants «étrangers «dans la synagogue. -

University Microfilms International

ANCIENT EUBOEA: STUDIES IN THE HISTORY OF A GREEK ISLAND FROM EARLIEST TIMES TO 404 B.C. Item Type text; Dissertation-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Vedder, Richard Glen, 1950- Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 11/10/2021 05:15:39 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/290465 INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1.The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. -

Cultic Connections in Pindar's Nemean 1

Cultic Connections in Pindar’s Nemean 1 This paper argues that Pindar’s evocation of Ortygia as the “hallowed breath of Alpheos” in the opening of Nemean 1 for Chromios of Aitna should be understood as an allusion to a wider network of the cult of the river god, Alpheos, shared by the Syracusans and the Peloponnesians. When Hieron founded Aitna, he recruited 5,000 Peloponnesians and 5,000 Syracusans as its new citizens (Diod. 11.49). Peloponnesian mercenaries moreover served in the armies of Gelon and Hieron and were likely granted Syracusan citizenship (Asheri). Recent scholarship has shown that myths in Pindar can unite communities (Foster), foment political change or maintain the status quo (Kowalzig), and advertise a city’s merits to panhellenic audiences (Hubbard). Understood in a context of Peloponnesian immigration to Sicily, the opening of Nemean 1 refers to Syracusan traditions connecting the Sicilian city not only to Olympia but also to a system of cult worship of Artemis Alpheioa in the Peloponnese. This cultic system emphasizes the shared tradition of the two populations Hieron in particular sought to unite. Interpreters who explain the opening line of Nemean 1 as a reference to Arethusa base their readings on the tradition that the Peloponnesian river Alpheos mixed its waters with the spring of Arethusa on the island of Ortygia in Syracuse (Dougherty, Foster). Literary evidence (Ibycus PMG 323, Paus. 5.7.3) and early Syracusan coinage confirm that Arethusa was an important civic symbol, and suggest that by the late 470s when Pindar composed Nemean 1, the bond between river and spring functioned as a metaphor for the city’s original foundation from Peloponnesians (Dougherty). -

From the Walls of Troy to the Canals of Venice Landmarks of Mediterranean Civilizations

FROM THE WALLS OF TROY TO THE CANALS OF VENICE Landmarks of Mediterranean Civilizations Private-Style Cruising Aboard the 50-Suite Corinthian September 12 – 23, 2013 Dear Traveler, From mythic prehistoric sites to magnificent Greek and Roman monuments, the Mediterranean features layer upon layer of history and culture set beautifully upon azure waters. Centuries of history imbue these shores, from ancient structures that remain remarkably intact to beautiful seaside walled towns that have retained their original character and architecture. And it was in these storied shores that our Western tradition was born. After the summer crowds have thinned, join us on a singularly unique cruise that is anchored between two historic cities of the sea, Istanbul and Venice. Each day you will revel in new vistas, historic and natural. Our voyage begins in Turkey—from the splendors of Istanbul to the walls of Troy and the magnificent monuments of Ephesus. Leaving the Anatolian coast, we journey to Crete, Zeus’s birthplace and home to the Labyrinth of the Minotaur at the remarkable palace of King Minos at Knossos. From here, Corinthian voyages to Syracuse in Sicily, one of the most important classical city-states, described by Cicero as the most beautiful of all Greek cities. Onward we travel to Otranto—once a Byzantine stronghold—on into the Adriatic, discovering back-to-back UNESCO World Heritage site ports in Montenegro and Croatia, and ending our journey in Venice, one of the world’s most remarkable cities. As our guides to the ancient cultures and empires we will encounter, we are privileged to have with us two renowned experts. -

Greek Colonization: Small and Large Islands Mario Lombardo

Mediterranean Historical Review Vol. 27, No. 1, June 2012, 73–85 Greek colonization: small and large islands Mario Lombardo Dipartimento di Beni Culturali, Universita` degli Studi del Salento, Lecce, Italy This article looks at the relation between insular identity and colonization, in Greek thought but also in Greek colonial practices; more precisely, it examines how islands of different sizes are perceived and presented in their role of ‘colonizing entities’, and as destinations of colonial undertakings. Size appears to play an important role: there seems to have been a tendency to settle small to medium sized islands with a single colony. Large islands too, such as Corsica and Sardinia, follow the pattern ‘one island – one polis’; the case of Sicily is very different, but even there, in a situation of crisis, a colonial island identity emerged. Similarly, a number of small to medium-sized single- polis islands of the Aegean acted as colonizing entities, although there is almost no mention of colonial undertakings by small and medium-sized Aegean islands that had more than one polis. Multi-polis islands, such as Rhodes or Crete – but not Euboea – are often presented as the ‘collective’ undertakers of significant colonial enterprises. Keywords: islands; insularity; identity; Greek colonization; Rhodes; Crete; Lesbos; Euboea; Sardinia; Corsica; Sicily 1. Islands are ubiquitous in the Mediterranean ecosystem, and particularly in the Aegean landscape; several important books have recently emphasized the important and manifold role played by insular locations in Antiquity.1 As ubiquitous presences in the Mediterranean scenery, islands also feature in the ancient Greek traditions concerning ‘colonial’ undertakings and practices. -

I QUADERNI DI Careggiissue 06

Issue 06 No. 06 I QUADERNI DI CAREGGI 6 / 2014 Common Goods from a Landscape Perspective Coordinators and Guest Editors: Saša Dobričič (University of Nova Gorica) Carlo Magnani (University I.U.A.V. of Venice) Bas Pedroli (University of Wageningen) Amy Strecker (University of Leiden) Quaderni di Careggi - Issue 06 / No. 6 - 5/2014 ISSN 2281-3195 In this number: Proceedings of the Sixth Careggi Seminar - Florence January 16-17, 2014 / Firenze 16-17 gennaio 2014 Scientific Editor: Dr. Amy Strecker: [email protected] Graphic layout: Fabrizio Bagatti - Organisation: Tessa Goodman - UNISCAPE - [email protected] - www.uniscape.eu Issue 06 No. 06 I QUADERNI DI CAREGGI 6 / 2014 Common Goods from a Landscape Perspective Coordinators and Guest Editors: Saša Dobričič (University of Nova Gorica) , Carlo Magnani (University I.U.A.V. of Venice) Bas Pedroli (University of Wageningen) , Amy Strecker (University of Leiden) Summary / Indice Introduction p. 3 Epistemology 5 L. Adli-Chebaiki, Pr.N. Chabby-Chemrouk Epistemological Draft on Landscape Syntax as a Common Good 5 M. Akasaka Whose View to Mount Fuji is in Tokyo? 9 A. Saavedra Cardoso Agro-Urbanism and the Right to Landscape Common Goods 15 M. Fiskervold Articulating Landscape as Common Good 20 C. Garau, P. Mistretta The Territory and City as a Common Good 26 C. Girardi From Commodity to Common Good: the Drama of the Landscape in Christo and Jeanne Claude 30 C. Mattiucci, S. Staniscia How to Deal with Landscape as a Common Good 34 L. Menatti Landscape as a Common Good: a Philosophical and Epistemological Analysis 40 J.M.Palerm The Requirement of Architecture for the Common Good 44 E. -

Relations Between Greek Settlers and Indigenous Sicilians at Megara Hyblaea, Syracuse, and Leontinoi in the 8Th and 7Th Centuries BCE

It’s Complicated: Relations Between Greek Settlers and Indigenous Sicilians at Megara Hyblaea, Syracuse, and Leontinoi in the 8th and 7th Centuries BCE Aaron Sterngass Professors Farmer, Edmonds, Kitroeff, and Hayton A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a Degree of Bachelor of Arts in the Departments of Classical Studies and History at Haverford College May 2019 i Table of Contents Table of Contents ................................................................................................................................ i Acknowledgements........................................................................................................................... iii Abstract ............................................................................................................................................ iv I. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................... 1 II. BACKGROUND INFORMATION PRE-750 BCE .................................................................................... 2 Greece ....................................................................................................................................................... 2 Euboea ...................................................................................................................................................... 4 Corinth ..................................................................................................................................................... -

The Island of the Sun: Spatial Aspect of Solstices in Early Greek Thought Tomislav Bilić

The Island of the Sun: Spatial Aspect of Solstices in Early Greek Thought Tomislav Bilić HE SOLSTICES are the defining moments in the annual solar motion. The phenomenon, representing the maxi- T mum solar distance from the equator (i.e., declination), is manifested both on the temporal and on the spatial level. With regard to the former, it entails recognition of the longest and the shortest daytimes of the year, with the length increas- ing from winter to summer solstice and decreasing during the remaining half of the year. This phenomenon is more pro- nounced with an increase in latitude, culminating in a 24-hour solstice daytime or night at ca. 66°. However, it is the spatial level that is discussed in this paper. The problem is approached by an analysis of several heliotropia, devices for marking or measuring solar turnings, and the Greek notion of solar turnings themselves, which is in its turn studied through discussion of the occurrences of the phrase τροπαὶ (ἠελίοιο) and its variants in traditional and in scientific texts.1 Both the name of the marking-device and the phrase with its 1 Both types of texts belong to a common Greek ethnographic context, which embraces a wide range of cultural phenomena. For the notion of ethnographic context see especially the works of M. Detienne: “The Myth of ‘Honeyed Orpheus’,” in R. L. Gordon (ed.), Myth, Religion and Society. Structuralist Essays by M. Detienne, L. Gernet, J.-P. Vernant and P. Vidal-Naquet (Cambridge 1981) 95–109, at 98–99, 106–109; The Gardens of Adonis.