Thesis Final Copy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Extent to Which the Common Law Is Applied in Determining What

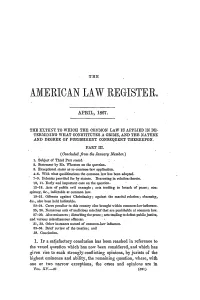

THE AMERICAN LAW REGISTER, APRIL, 1867. THE EXTE'N"IT TO WHICH THE COM ON LAW IS APPLIED IN DE- TERMINING WHAT CONSTITUTES A CRIME, AND THE NATURE AND DEGREE OF PUNISHMENT CONSEQUENT THEREUPON. PART III. (Concluded from the January.umber.) 1. Subject of Third. Part stated. 2. Statement by .Mr. Wheaton on tie question. 3. Exceptional states as to common-law application. 4-6. With what qualifications the common law has been adopted. 7-9. Felonies provided for by statute. Reasoning in relation thereto. 10, 11. Early and important case on the question. 12-18. Acts of public evil example; acts tending to breach of peace; con- -piracy, &c., indictable at common law. 19-21. Offences against Christianity; against the marital relation; obscenity, &c., also been held indictable. 22-24. Cases peculiar to this country also brought within common-law influence. 25, 26. 'Numerous acts of malicious mischief that are punishable at common law. 27-30. Also nuisances ; disturbing the peace; acts tenxding to defeat public justice. and various miscellaneous offences. 31, 32. Other instances named of common-law influence. 33-36. Brief review of the treatise; and 38. Conclusion. 1. IF a satisfactory conclusion has been reached in reference to the vexed question which has now been considered, and which has given rise to such strongly-conflicting opinions, by jurists of the highest eminence and ability, the remaining question, where, with one or two narrow exceptions, the eases and opinions are in VOL. XV.-21 (321) APPLICATION OF THE COMMON LAW almost perfect accord, cannot be attended with much difficulty. -

Vania Is Especi

THE PUNISHMENT OF CRIME IN PROVINCIAL PENNSYLVANIA HE history of the punishment of crime in provincial Pennsyl- vania is especially interesting, not only as one aspect of the Tbroad problem of the transference of English institutions to America, a phase of our development which for a time has achieved a somewhat dimmed significance in a nationalistic enthusiasm to find the conditioning influence of our development in that confusion and lawlessness of our own frontier, but also because of the influence of the Quakers in the development df our law. While the general pat- tern of the criminal law transferred from England to Pennsylvania did not differ from that of the other colonies, in that the law and the courts they evolved to administer the law, like the form of their cur- rency, their methods of farming, the games they played, were part of their English cultural heritage, the Quakers did arrive in the new land with a new concept of the end of the criminal law, and proceeded immediately to give force to this concept by statutory enactment.1 The result may be stated simply. At a time when the philosophy of Hobbes justified any punishment, however harsh, provided it effec- tively deterred the occurrence of a crime,2 when commentators on 1 Actually the Quakers voiced some of their views on punishment before leaving for America in the Laws agreed upon in England, wherein it was provided that all pleadings and process should be short and in English; that prisons should be workhouses and free; that felons unable to make satisfaction should become bond-men and work off the penalty; that certain offences should be published with double satisfaction; that estates of capital offenders should be forfeited, one part to go to the next of kin of the victim and one part to the next of kin of the criminal; and that certain offences of a religious and moral nature should be severely punished. -

The Opening of the Atlantic World: England's

THE OPENING OF THE ATLANTIC WORLD: ENGLAND’S TRANSATLANTIC INTERESTS DURING THE REIGN OF HENRY VIII By LYDIA TOWNS DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at The University of Texas at Arlington May, 2019 Arlington, Texas Supervising Committee: Imre Demhardt, Supervising Professor John Garrigus Kathryne Beebe Alan Gallay ABSTRACT THE OPENING OF THE ATLANTIC WORLD: ENGLAND’S TRANSATLANTIC INTERESTS DURING THE REIGN OF HENRY VIII Lydia Towns, Ph.D. The University of Texas at Arlington, 2019 Supervising Professor: Imre Demhardt This dissertation explores the birth of the English Atlantic by looking at English activities and discussions of the Atlantic world from roughly 1481-1560. Rather than being disinterested in exploration during the reign of Henry VIII, this dissertation proves that the English were aware of what was happening in the Atlantic world through the transnational flow of information, imagined the potentials of the New World for both trade and colonization, and actively participated in the opening of transatlantic trade through transnational networks. To do this, the entirety of the Atlantic, all four continents, are considered and the English activity there analyzed. This dissertation uses a variety of methods, examining cartographic and literary interpretations and representations of the New World, familial ties, merchant networks, voyages of exploration and political and diplomatic material to explore my subject across the social strata of England, giving equal weight to common merchants’ and scholars’ perceptions of the Atlantic as I do to Henry VIII’s court. Through these varied methods, this dissertation proves that the creation of the British Atlantic was not state sponsored, like the Spanish Atlantic, but a transnational space inhabited and expanded by merchants, adventurers and the scholars who created imagined spaces for the English. -

Abolishing the Crime of Public Nuisance and Modernising That of Public Indecency

International Law Research; Vol. 6, No. 1; 2017 ISSN 1927-5234 E-ISSN 1927-5242 Published by Canadian Center of Science and Education Abolishing the Crime of Public Nuisance and Modernising That of Public Indecency Graham McBain1,2 1 Peterhouse, Cambridge, UK 2 Harvard Law School, USA Correspondence: Graham McBain, 21 Millmead Terrace, Guildford, Surrey GU2 4AT, UK. E-mail: [email protected] Received: November 20, 2016 Accepted: February 19, 2017 Online Published: March 7, 2017 doi:10.5539/ilr.v6n1p1 URL: https://doi.org/10.5539/ilr.v6n1p1 1. INTRODUCTION Prior articles have asserted that English criminal law is very fragmented and that a considerable amount of the older law - especially the common law - is badly out of date.1 The purpose of this article is to consider the crime of public nuisance (also called common nuisance), a common law crime. The word 'nuisance' derives from the old french 'nuisance' or 'nusance' 2 and the latin, nocumentum.3 The basic meaning of the word is that of 'annoyance';4 In medieval English, the word 'common' comes from the word 'commune' which, itself, derives from the latin 'communa' - being a commonality, a group of people, a corporation.5 In 1191, the City of London (the 'City') became a commune. Thereafter, it is usual to find references with that term - such as common carrier, common highway, common council, common scold, common prostitute etc;6 The reference to 'common' designated things available to the general public as opposed to the individual. For example, the common carrier, common farrier and common innkeeper exercised a public employment and not just a private one. -

Annual Report 2009-2010

Contents The Department Introduction……………………………………………………….………………………2 Staff and affiliates………………………………………………….…………………….4 Visitors and students……………………………………………….……………………5 Comings and goings………………………………………………..……………………6 Roles and responsibilities………………………………………….……………………6 Prizes, projects and honours……………………………………………………………8 Seminars and special lectures…………………………………….……………………10 Students Student statistics…………………………………………………………………………12 Part II essay and dissertation titles…………………………………………………….13 MPhil and Part III essay and dissertation titles……………………………………….17 PhD theses………………………………………………………………………………..22 Transferable skills………………………………………………………………………..24 The Library Annual report of the Whipple Library……………………………………………..……29 The Museum Annual report of the Whipple Museum of the History of Science………………..…33 Individuals Annual reports of members of the Department………….……………………………45 Seminar Programmes Michaelmas Term 2009…………………………………………………………………101 Lent Term 2010……………………………………………………………………….…112 Easter Term 2010…………………………………………………………………….…122 Department of History and Philosophy of Science, University of Cambridge Free School Lane, Cambridge, CB2 3RH Telephone: 01223 334500 Fax: 01223 334554 www.hps.cam.ac.uk 1 The Department Introduction Welcome to the 2009–10 Annual Report. It was another busy year for the Department of History and Philosophy of Science and many of the main activities were to do with people and staffing, highlighting the fact that it is the people who make the Department a success. Liba Taub was successful in her application for promotion to Professor and Tim Lewens was successful in his application for promotion to Reader, and we would like to congratulate them both on their new positions which commence in October 2010. During the course of the year Hasok Chang was appointed as the Department’s Rausing Professor, taking up the post previously held by Peter Lipton. Hasok joined the Department in September 2010 and we would like to extend our warm welcomes to him. -

Old-Time Punishments

Presented to the UNIVERSITY OF TORONTO LIBRARY by the ONTARIO LEGISLATIVE LIBRARY 1980 (\V\ 7- OLD-TIME PUNISHMENTS. WORKS BY WILLIAM ANDREWS, F.R.H.S. Mr. William Andrews has produced several books of singular value in their historical and archaeological character. He has a genius for digging among dusty parchments and old books, and for bringing out from among them that which it is likely the public of to-day will care to read. Scotsman. Curiosities of the Church. A volume both entertaining and instructive, throwing much light on the manners and customs of bygone generations of Churchmen, and will be read to-day with much interest. Nftitbery House Magazine. An extremely interesting volume. North British Daily Mail. A work of lasting interest. Hull Kxaminer. Full of interest. The Globe. The reader will find much in this book to interest, instruct, and amuse. Home Chimes. We feel sure that many will feel grateful to Mr. Andrews for having produced such an interesting book. The Antiquary. Historic Yorkshire. Cuthbert Bede, the popular author of "Verdant Green," writing to Society, says: "Historic Yorkshire," by William Andrews, will be of great interest and value to everyone connected with England's largest county. Mr. Andrews not only writes with due enthusiasm for his subject, but has arranged and marshalled his facts and figures with great skill, and produced a thoroughly popular work that will be read eagerly and with advantage. Historic Romance. STRANGE STORIES, CHARACTERS, SCENES, MYSTERIES, AND MEMORABLE EVENTS IN THE HISTORY OF OLD ENGLAND. In his present work Mr. Andrews has traversed a wider field than in his last book, "Historic Yorkshire," but it is marked by the same painstaking care for accuracy, and also by the pleasant way in which he popularises strange stories and out-of-the-way scenes in English History. -

Unusual Punishments” in Anglo- American Law: the Ed Ath Penalty As Arbitrary, Discriminatory, and Cruel and Unusual John D

Northwestern Journal of Law & Social Policy Volume 13 | Issue 4 Article 2 Spring 2018 The onceptC of “Unusual Punishments” in Anglo- American Law: The eD ath Penalty as Arbitrary, Discriminatory, and Cruel and Unusual John D. Bessler Recommended Citation John D. Bessler, The Concept of “Unusual Punishments” in Anglo-American Law: The Death Penalty as Arbitrary, Discriminatory, and Cruel and Unusual, 13 Nw. J. L. & Soc. Pol'y. 307 (2018). https://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/njlsp/vol13/iss4/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Northwestern Pritzker School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Northwestern Journal of Law & Social Policy by an authorized editor of Northwestern Pritzker School of Law Scholarly Commons. Copyright 2018 by Northwestern University Pritzker School of Law `Vol. 13, Issue 4 (2018) Northwestern Journal of Law and Social Policy The Concept of “Unusual Punishments” in Anglo-American Law: The Death Penalty as Arbitrary, Discriminatory, and Cruel and Unusual John D. Bessler* ABSTRACT The Eighth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution, like the English Bill of Rights before it, safeguards against the infliction of “cruel and unusual punishments.” To better understand the meaning of that provision, this Article explores the concept of “unusual punishments” and its opposite, “usual punishments.” In particular, this Article traces the use of the “usual” and “unusual” punishments terminology in Anglo-American sources to shed new light on the Eighth Amendment’s Cruel and Unusual Punishments Clause. The Article surveys historical references to “usual” and “unusual” punishments in early English and American texts, then analyzes the development of American constitutional law as it relates to the dividing line between “usual” and “unusual” punishments. -

Critics Duped by Reds' Propaganda WASHINGTON (AP) — Eagleton's Past Psychiatric Is Vietnam, and Nixon In- President Said

Court Challenge SEE STORY BELOW The Weather THEDAILY FINAL Partly cloudy today, mgn around 80. Fair tonight. Most- ) Red Bank, Freehold ~T~ ly sunny tomorrow and Sun- I Long Branch 1 day, little temperature EDITION change. 24 PAGES Momnoutli Comity's Outstanding Home Newspaper VOL.95 NO.24 RED BANK, NJ. FRIDAY, JULY 28,1972 TENCENTS ' McGann Voids Common-Scold By HALLIE SCHRAEGER "A man might be 'trouble- took a swipe a( New Jersey's carry a pocket edition of for his definition of a common Judge McGann commented S. A. 2A:85-1 purports to make some and angry' and, by his "catch-all" statute (N. J. S; Blackstone with him." scold: "a public nuisance to in a footnote that the specified criminal the common law of- FREEHOLD — Finding the 'brawling and wrangling A. 2A:85-1), which, he said, is Sir William Blackstone her neighborhood, for which penalty constitutes cruel and fense of being a common ancient common law charge among' his 'neighbors, break "all that the average person (1723-1780), the most famous, offense she may be indicted unusual punishment.) scold, it is void because of its of being a "common scold" the' peace, increase discord^ has to guide his conduct." of English jurists, was the au- and, if convicted, shall be sen- "To a die-hard male chau- vagueness and is con- outmoded, unconstitutionally and become a nuisance to the Judge McGann said that thor ofi "Commentaries on the tenced to be placed in a cer- vinist, the public utterances of stitutionally unenforceable," vague and discriminatory, Su- neighborhood,' yet he could statute tells the average per- Laws of England" (1775) still tain engine of correction a dedicated woman's liber- be said. -

Criminal Law Act 1967

Criminal Law Act 1967 CHAPTER 58 ARRANGEMENT OF SECTIONS PART I FELONY AND MISDEMEANOUR Section 1. Abolition of distinction between felony and misdemeanour. 2. Arrest without warrant. 3. Use of force in making arrest, etc. 4. Penalties for assisting offenders. 5. Penalties for concealing offences or giving false information. 6. Trial of offences. 7. Powers of dealing with offenders. 8. Jurisdiction of quarter sessions. 9. Pardon. 10. Amendments of particular enactments, and repeals. 11. Extent of Part I, and provision for Northern Ireland. 12. Commencement, savings, and other general provisions. PART II OBSOLETE CRIMES 13. Abolition of certain offences, and consequential repeals. PART III SUPPLEMENTARY 14. Civil rights in respect of maintenance and champerty. 15. Short title. SCHEDULES : Schedule 1-Lists of offences falling, or not falling, within jurisdiction of quarter sessions. Schedule 2-Supplementary amendments. Schedule 3-Repeals (general). Schedule 4--Repeals (obsolete crimes). A Criminal Law Act 1967 CH. 58 1 ELIZABETH II 1967 CHAPTER 58 An Act to amend the law of England and Wales by abolishing the division of crimes into felonies and misdemeanours and to amend and simplify the law in respect of matters arising from or related to that division or the abolition of it; to do away (within or without England and Wales) with certain obsolete crimes together with the torts of maintenance and champerty; and for purposes connected therewith. [21st July 1967] BE IT ENACTED by the Queen's most Excellent Majesty, by and with the advice and consent of the Lords Spiritual and Temporal, and Commons, in this present Parliament assembled, and by the authority of the same, as follows:- PART I FELONY AND MISDEMEANOUR 1.-(1) All distinctions between felony and misdemeanour are Abolition of abolished. -

Third Party Funding in Australia and Europe” Dr

Searle Civil Justice Institute Public Policy Initiative: Third-Party Financing of Litigation: Civil Justice Friend or Foe? “Third Party Funding in Australia and Europe” Dr. George R. Barker Working Paper – Please do not cite December 21, 2011 (c) George Barker – 13 December 2011 All rights reserved Centre for Law and Economics Ltd 2011 Contents INTRODUCTION AND OUTLINE ....................................................................... 3 PART I: ECONOMICS OF LITIGATION FUNDING ............................................ 4 PART II: LITIGATION FUNDING IN AUSTRALIA .............................................7 Section A. The Evolution of Legal Rules on Litigation Funders in Australia ..............7 A. Maintenance, & Champerty ................................................................... 8 B. Lawyers and Contingency Fees ............................................................ 15 C. Adverse Costs Orders .......................................................................... 16 D. Federal Regulation............................................................................... 17 Section B. Litigation Funders in Australia .............................................................. 21 A. Funders ............................................................................................... 21 B. Selection of Cases .............................................................................. 22 C. Commissions & Other Relevant Criteria .............................................. 28 D. Success rates ..................................................................................... -

The Law of Crimes

THE Law of Crimes. By JOHN WILDER MAY, CHIEF JUSTICE OF THE MUNICIPAL COURT, AND LATE PROSECUTING OFFICER FOR BOSTON. BOSTON: LITTLE, BROWN, AND COMPANY. 1881. T M Copyright, 1880, By John Wilder Mat. 3332- 2_3 University Press : John Wilson and Son, Cambridge. PREFACE. In the following pages the author has endeavored to state briefly the general principles underlying the Criminal Law, and to define the several common- law crimes, and such statutory crimes — mala in se, and not merely mala prohibita or police regulations 1 — as may be said to be common statute crimes. The brevity of this treatise did not admit of a history of what the law has been, nor a discussion of what it ought to be ; but only a statement of what it is. In the cases cited will be found ample learning upon the first of these points. Digressions upon the second would be out of place in a book designed as a lawyer's and student's hand-book. The alphabetical arrangement has been adopted in the second chapter, as, on the whole, more convenient for the practising lawyer. The student, however, will perhaps find it to his advantage, on first peru- 1 On the question of the limitation of this power of police regu- lation, see 2 Kent's Com. 840; Com. v. Alger, 7 Cush. (Mass.) 63; Thorp v. R. & B. Railroad Co., 27 Vt. 149 ; Slaughter-House Cases, 16 Wall. (U. S.) 36. IV PREFACE. sal, instead of reading consecutively, to pursue the more scientific method of grouping the titles ; taking first, for instance, crimes against the person, — as Assault, Homicide, and the other crimes where force applied to the person is a leading characteristic ; then crimes against property, — as Larceny, Embezzle- ment, Cheating, False Pretences, and the like, where fraud is a leading characteristic ; to be followed by Robbery, Burglary, Arson, Malicious Mischief; and concluding with such crimes as militate against the public peace, safety, morals, good order, and policy, — as Nuisances generally, Treason, Blasphemy, Libel, Adultery, and the like. -

Abolishing the Common Law Offence of Keeping a Disorderly House

Journal of Politics and Law; Vol. 8, No. 2; 2015 ISSN 1913-9047 E-ISSN 1913-9055 Published by Canadian Center of Science and Education Abolishing the Common Law Offence of Keeping a Disorderly House Graham McBain1,2 1 Peterhouse, Cambridge, UK 2 Harvard Law School, USA Correspondence: Graham McBain, 21 Millmead Terrace, Guildford, Surrey GU2 4AT, UK. E-mail: [email protected] Received: December 5, 2014 Accepted: December 22, 2014 Online Published: May 27, 2015 doi:10.5539/jpl.v8n2p17 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.5539/jpl.v8n2p17 1. Introduction A previous article has reviewed the law in relation to escape, prison breach and rescue1 which, it argues, should now be made statutory offences. This article looks at another common law offence - one of ‘keeping a disorderly house’- which, it is asserted, should be abolished, being obsolete. In medieval times - especially in London - this crime was designed to suppress brothels as well as other sexual conduct (such as adultery and fornication) which it was deemed appropriate for the criminal law to punish. Thus, in respect of the latter, it appears it was a London custom that a constable - on receipt of an information - had the legal right to enter a house where a person was suspected of committing adultery or fornication and ‘carry them to prison.’2 From ‘disorderly house’ being a reference to a place where socially unacceptable sexual activity was carried on, the concept was extended to cover common gaming houses. Also, to play houses (theatres),3 common inns and ‘common’ houses (that is, ones to which the public had access) where cock-fights were held; Since these places also tended to be venues for illicit sexual activity, it is understandable how they came to be embraced within the concept.