Judicial Legislation in Criminal Law

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Charging Language

1. TABLE OF CONTENTS Abduction ................................................................................................73 By Relative.........................................................................................415-420 See Kidnapping Abuse, Animal ...............................................................................................358-362,365-368 Abuse, Child ................................................................................................74-77 Abuse, Vulnerable Adult ...............................................................................78,79 Accessory After The Fact ..............................................................................38 Adultery ................................................................................................357 Aircraft Explosive............................................................................................455 Alcohol AWOL Machine.................................................................................19,20 Retail/Retail Dealer ............................................................................14-18 Tax ................................................................................................20-21 Intoxicated – Endanger ......................................................................19 Disturbance .......................................................................................19 Drinking – Prohibited Places .............................................................17-20 Minors – Citation Only -

Extent to Which the Common Law Is Applied in Determining What

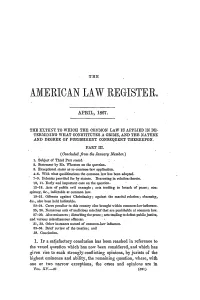

THE AMERICAN LAW REGISTER, APRIL, 1867. THE EXTE'N"IT TO WHICH THE COM ON LAW IS APPLIED IN DE- TERMINING WHAT CONSTITUTES A CRIME, AND THE NATURE AND DEGREE OF PUNISHMENT CONSEQUENT THEREUPON. PART III. (Concluded from the January.umber.) 1. Subject of Third. Part stated. 2. Statement by .Mr. Wheaton on tie question. 3. Exceptional states as to common-law application. 4-6. With what qualifications the common law has been adopted. 7-9. Felonies provided for by statute. Reasoning in relation thereto. 10, 11. Early and important case on the question. 12-18. Acts of public evil example; acts tending to breach of peace; con- -piracy, &c., indictable at common law. 19-21. Offences against Christianity; against the marital relation; obscenity, &c., also been held indictable. 22-24. Cases peculiar to this country also brought within common-law influence. 25, 26. 'Numerous acts of malicious mischief that are punishable at common law. 27-30. Also nuisances ; disturbing the peace; acts tenxding to defeat public justice. and various miscellaneous offences. 31, 32. Other instances named of common-law influence. 33-36. Brief review of the treatise; and 38. Conclusion. 1. IF a satisfactory conclusion has been reached in reference to the vexed question which has now been considered, and which has given rise to such strongly-conflicting opinions, by jurists of the highest eminence and ability, the remaining question, where, with one or two narrow exceptions, the eases and opinions are in VOL. XV.-21 (321) APPLICATION OF THE COMMON LAW almost perfect accord, cannot be attended with much difficulty. -

Vania Is Especi

THE PUNISHMENT OF CRIME IN PROVINCIAL PENNSYLVANIA HE history of the punishment of crime in provincial Pennsyl- vania is especially interesting, not only as one aspect of the Tbroad problem of the transference of English institutions to America, a phase of our development which for a time has achieved a somewhat dimmed significance in a nationalistic enthusiasm to find the conditioning influence of our development in that confusion and lawlessness of our own frontier, but also because of the influence of the Quakers in the development df our law. While the general pat- tern of the criminal law transferred from England to Pennsylvania did not differ from that of the other colonies, in that the law and the courts they evolved to administer the law, like the form of their cur- rency, their methods of farming, the games they played, were part of their English cultural heritage, the Quakers did arrive in the new land with a new concept of the end of the criminal law, and proceeded immediately to give force to this concept by statutory enactment.1 The result may be stated simply. At a time when the philosophy of Hobbes justified any punishment, however harsh, provided it effec- tively deterred the occurrence of a crime,2 when commentators on 1 Actually the Quakers voiced some of their views on punishment before leaving for America in the Laws agreed upon in England, wherein it was provided that all pleadings and process should be short and in English; that prisons should be workhouses and free; that felons unable to make satisfaction should become bond-men and work off the penalty; that certain offences should be published with double satisfaction; that estates of capital offenders should be forfeited, one part to go to the next of kin of the victim and one part to the next of kin of the criminal; and that certain offences of a religious and moral nature should be severely punished. -

Criminal Code 2003.Pmd 273 11/27/2004, 12:35 PM 274 No

273 No. 9 ] Criminal Code [2004. SAINT LUCIA ______ No. 9 of 2004 ARRANGEMENT OF SECTIONS CHAPTER ONE General Provisions PART I PRELIMINARY Section 1. Short title 2. Commencement 3. Application of Code 4. General construction of Code 5. Common law procedure to apply where necessary 6. Interpretation PART II JUSTIFICATIONS AND EXCUSES 7. Claim of right 8. Consent by deceit or duress void 9. Consent void by incapacity 10. Consent by mistake of fact 11. Consent by exercise of undue authority 12. Consent by person in authority not given in good faith 13. Exercise of authority 14. Explanation of authority 15. Invalid consent not prejudicial 16. Extent of justification 17. Consent to fight cannot justify harm 18. Consent to killing unjustifiable 19. Consent to harm or wound 20. Medical or surgical treatment must be proper 21. Medical or surgical or other force to minors or others in custody 22. Use of force, where person unable to consent 23. Revocation annuls consent 24. Ignorance or mistake of fact criminal code 2003.pmd 273 11/27/2004, 12:35 PM 274 No. 9 ] Criminal Code [2004. 25. Ignorance of law no excuse 26. Age of criminal responsibility 27. Presumption of mental disorder 28. Intoxication, when an excuse 29. Aider may justify same force as person aided 30. Arrest with or without process for crime 31. Arrest, etc., other than for indictable offence 32. Bona fide assistant and correctional officer 33. Bona fide execution of defective warrant or process 34. Reasonable use of force in self-defence 35. Defence of property, possession of right 36. -

American Influence on Israel's Jurisprudence of Free Speech Pnina Lahav

Hastings Constitutional Law Quarterly Volume 9 Article 2 Number 1 Fall 1981 1-1-1981 American Influence on Israel's Jurisprudence of Free Speech Pnina Lahav Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/ hastings_constitutional_law_quaterly Part of the Constitutional Law Commons Recommended Citation Pnina Lahav, American Influence on Israel's Jurisprudence of Free Speech, 9 Hastings Const. L.Q. 21 (1981). Available at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hastings_constitutional_law_quaterly/vol9/iss1/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Hastings Constitutional Law Quarterly by an authorized editor of UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ARTICLES American Influence on Israel's Jurisprudence of Free Speech By PNINA LAHAV* Table of Contents Introduction ........................................................ 23 Part 1: 1953-Enter Probable Danger ............................... 27 A. The Case of Kol-Ha'am: A Brief Summation .............. 27 B. The Recipient System on the Eve of Transplantation ....... 29 C. Justice Agranat: An Anatomy of Transplantation, Grand Style ...................................................... 34 D. Jurisprudence: Interest Balancing as the Correct Method to Define the Limitations on Speech .......................... 37 1. The Substantive Material Transplanted ................. 37 2. The Process of Transplantation -

No. 11-210 in the Supreme Court of the United States ______UNITED STATES of AMERICA, Petitioner, V

No. 11-210 In the Supreme Court of the United States ______________________________________________ UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, Petitioner, v. XAVIER ALVAREZ, Respondent. ___________________________________________ ON THE WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE NINTH CIRCUIT __________________________________________ AMICUS CURIAE BRIEF OF THE THOMAS JEFFERSON CENTER FOR THE PROTECTION OF FREE EXPRESSION IN SUPPORT OF RESPONDENT BRUCE D. BROWN J. JOSHUA WHEELER* BAKER HOSTETLER LLP JESSE HOWARD BAKER IV WASHINGTON SQUARE The Thomas Jefferson 1050 Connecticut Avenue, NW Center for the Protection of Washington, DC 20036-5304 Free Expression P: 202-861-1660 400 Worrell Drive [email protected] Charlottesville, VA 22911 P: 434-295-4784 KATAYOUN A. DONNELLY [email protected] BAKER HOSTETLER LLP 303 East 17th Avenue Denver, CO 80203-1264 303-861-4038 [email protected] *Counsel of Record for Amicus Curiae TABLE OF CONTENTS Page TABLE OF AUTHORITIES .................................... iv STATEMENT OF INTEREST OF AMICUS CURIAE ................................................................... 1 SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT .................................. 1 ARGUMENT ............................................................. 3 I. THE STOLEN VALOR ACT CREATES AN UNPROTECTED CATEGORY OF SPEECH NOT PREVIOUSLY RECOGNIZED IN THIS COURT‘S FIRST AMENDMENT DECISIONS. A. The statute does not regulate fraudulent or defamatory speech. ............. 4 B. The historical tradition of stringent restrictions on the speech of military personnel does not encompass false statements about military service made by civilians ........................................ 5 II. HISTORY REJECTS AN EXCEPTION TO THE FIRST AMENDMENT BASED ON PROTECTING THE REPUTATION OF GOVERNMENT INSTITUTIONS. A. Origins of seditious libel laws. ................... 8 B. The court‘s reflections on seditious libel laws. .................................................. 11 ii III. NEITHER CONGRESS NOR THE COURTS MAY SIMPLY CREATE NEW CATEGORIES OF UNPROTECTED SPEECH BASED ON A BALANCING TEST. -

Marshall Islands Consolidated Legislation

Criminal Code [31 MIRC Ch 1] http://www.paclii.org/mh/legis/consol_act/cc94/ Home | Databases | WorldLII | Search | Feedback Marshall Islands Consolidated Legislation You are here: PacLII >> Databases >> Marshall Islands Consolidated Legislation >> Criminal Code [31 MIRC Ch 1] Database Search | Name Search | Noteup | Download | Help Criminal Code [31 MIRC Ch 1] 31 MIRC Ch 1 MARSHALL ISLANDS REVISED CODE 2004 TITLE 31. - CRIMES AND PUNISHMENTS CHAPTER 1. CRIMINAL CODE ARRANGEMENT OF SECTIONS Section PART I - GENERAL PROVISIONS §101 . Short title. §102 . Classification of crimes. §103. Definitions, Burden of Proof; General principles of liability; Requirements of culpability. §104 . Accessories. §105 . Attempts. §106 . Insanity. §107 . Presumption as to responsibility of children. §108 . Limitation of prosecution. §109. Limitation of punishment for crimes in violation of native customs. PART II - ABUSE OF PROCESS §110 . Interference with service of process. §111 .Concealment, removal or alteration of record or process. PART III - ARSON §112 . Defined; punishment. PART IV - ASSAULT AND BATTERY §113 . Assault. §114 . Aggravated assault. §115 . Assault and battery. §116 . Assault and battery with a dangerous weapon. 1 of 37 25/08/2011 14:51 Criminal Code [31 MIRC Ch 1] http://www.paclii.org/mh/legis/consol_act/cc94/ PART V - BIGAMY §117 . Defined; punishment. PART VI - BRIBERY §118 . Defined; punishment. PART VII - BURGLARY §119. Defined; punishment. PART VIII - CONSPIRACY §120 . Defined, punishment. PART IX – COUNTERFEITING §121 . Defined; punishment. PART X - DISTURBANCES, RIOTS, AND OTHER CRIMES AGAINST THE PEACE §122 . Disturbing the peace. §123 . Riot. §124. Drunken and disorderly conduct. §125 . Affray. §126 . Security to keep the peace. PART XI - ESCAPE AND RESCUE §127. Escape. -

Gfniral Statutes

GFNIRAL STATUTES OF THE STATE OF MINNESOTA, IN FOROE JANUARY, 1891. VOL.2. CowwNnro ALL TEE LAw OP & GENERAJ NATURE Now IN FORCE AND NOT IN VOL. 1, THE SAME BEING TEE CODE OF Civu PROCEDURE AND ALL REME- DIAL LAW, THE PROBATE CODE, THE PENAL CODE AND THE CEnt- JRAL PROCEDURE, THE CoNSTITuTIoNS AND ORGANIc ACTS. COMPILED AND ANNOTATED BY JNO. F. KELLY, OF TUE Sr. Pui BAR. SECOND EDITION. ST. PAUL: PUBLISHED BY THE AUTHOR 1891. A MINNESOTA STATUTES 1891 IN] EX To Vols. 1 and , except as Indicated by the cross-references, to Vol. 1. A - ACCOUNTS. (cqinued)-- officers'., of corporation, altering, §6448. ABANDONMNT (see CHILD)- presentation, of fraudulent, when felony, Qf, insane person, penalty fpr, §5895, §6507. of lands condemned for public use, §1229. ABATE- ACCOUN,T BOOKS- reognizance.not to abate, when, §439. • are p'rirna.facie evidence, §51'12. action to, nuisapee, §*442 ACCUSATION- actions abated when, §4738. to remove attorneys, §4376. board of health, sa,ll, hat,nuisapces, i9, %vriting. veiifipd, '4l77. §5SS, 589.. ACCUSED- warrant to, §591. rigMsof; §6626 ABBREViATIONS- iii describing lands, §1582. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS (see Index to 'Vol. ABDUCTION (see SEDUCTION; KTDNAP- of 1eeds of land, §4121. RING)-. certifipa.te of. §4122. defined, pnnishment,f,or, §6196. ii qter.sta,tes, §4.23. evidence required to cnvitof, §6197. in foreign countries. §4124. ABETTING (see AIDIN-)- iefusaI to aknplege, §4125. ABOLISHED- proceedings to eompl, §4126. dower anl curtesy is, §4001.. defective, to, cqnveyanqes legalized-. certain defects legalized, §4164. ABORTION (see INDECENT ARTICLES)- ntnslapghter in first degree, when, by officer whose ternl. has çxpired, §4165, §6H5, GUll. -

Abolishing the Crime of Public Nuisance and Modernising That of Public Indecency

International Law Research; Vol. 6, No. 1; 2017 ISSN 1927-5234 E-ISSN 1927-5242 Published by Canadian Center of Science and Education Abolishing the Crime of Public Nuisance and Modernising That of Public Indecency Graham McBain1,2 1 Peterhouse, Cambridge, UK 2 Harvard Law School, USA Correspondence: Graham McBain, 21 Millmead Terrace, Guildford, Surrey GU2 4AT, UK. E-mail: [email protected] Received: November 20, 2016 Accepted: February 19, 2017 Online Published: March 7, 2017 doi:10.5539/ilr.v6n1p1 URL: https://doi.org/10.5539/ilr.v6n1p1 1. INTRODUCTION Prior articles have asserted that English criminal law is very fragmented and that a considerable amount of the older law - especially the common law - is badly out of date.1 The purpose of this article is to consider the crime of public nuisance (also called common nuisance), a common law crime. The word 'nuisance' derives from the old french 'nuisance' or 'nusance' 2 and the latin, nocumentum.3 The basic meaning of the word is that of 'annoyance';4 In medieval English, the word 'common' comes from the word 'commune' which, itself, derives from the latin 'communa' - being a commonality, a group of people, a corporation.5 In 1191, the City of London (the 'City') became a commune. Thereafter, it is usual to find references with that term - such as common carrier, common highway, common council, common scold, common prostitute etc;6 The reference to 'common' designated things available to the general public as opposed to the individual. For example, the common carrier, common farrier and common innkeeper exercised a public employment and not just a private one. -

Choctaw Nation Criminal Code

Choctaw Nation Criminal Code Table of Contents Part I. In General ........................................................................................................................ 38 Chapter 1. Preliminary Provisions ............................................................................................ 38 Section 1. Title of code ............................................................................................................. 38 Section 2. Criminal acts are only those prescribed ................................................................... 38 Section 3. Crime and public offense defined ............................................................................ 38 Section 4. Crimes classified ...................................................................................................... 38 Section 5. Felony defined .......................................................................................................... 39 Section 6. Misdemeanor defined ............................................................................................... 39 Section 7. Objects of criminal code .......................................................................................... 39 Section 8. Conviction must precede punishment ...................................................................... 39 Section 9. Punishment of felonies ............................................................................................. 39 Section 10. Punishment of misdemeanor ................................................................................. -

![Chap. 10.] OFFENCES AGAINST PUBLIC JUSTICE](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9302/chap-10-offences-against-public-justice-949302.webp)

Chap. 10.] OFFENCES AGAINST PUBLIC JUSTICE

Chap. 10.] OFFENCES AGAINST PUBLIC JUSTICE. CHAPTER X. OF OFFENCES AGAINST PUBLIC JUSTICE. THE order of our distribution will next lead us to take into consideration such crimes and misdemeanors as more especially affect the commonwealth, or public polity of the kingdom: which, however, as well as those which are pecul- iarly pointed against the lives and security of private subjects, are also offences against the king, as the pater-familiasof the nation: to whom it appertains by his regal office to protect the community, and each individual therein, from every degree of injurious violence, by executing those laws which the people them- selves in conjunction with him have enacted; or at least have consented to, by an agreement either expressly made in the persons of their representatives, or by a tacit and implied consent presumed from and proved by immemorial usage. The species of crimes which we have now before us is subdivided into such a number of inferior and subordinate classes, that it would much exceed the bounds of an elementary treatise, and be insupportably tedious to the reader, were I to examine them all minutely, or with any degree of critical accuracy. I shall therefore confine myself principally to general definitions, or descriptions of this great variety of offences, and to the punishments inflicted by law for each particular offence; with now and then a few incidental observations: referring the student for more particulars to other voluminous authors; who have treated of these subjects with greater precision and more in detail than is consistent with the plan of these Commentaries. -

Criminal Law. Merger of Conspiracy Into Completed

RECENT CASES the beneficial owners to avoid the statutory liability. Corker v. Soper 53 F. (2d) igo (C.C.A. 5th 1931); 45 Harv. L. Rev. 580 (1932). There, since, the holding did not con- sist of a majority of the shares, obviously no centralization of control of the company was intended. The parent company in the principal case can be distinguished in that its primary purpose was to centralize control. In both cases, however, the fact that the holding companies were inadequately financed to meet the contingent liability attach- ing to bank stock can be considered as indicating an attempted evasion of the statute. To determine when a holding company is so inadequately financed as to justify a dis- regard of the corporate entity to the extent of holding its stockholders personally liable, its assets must be carefully scrutinized. Since the purpose of the statute is to provide a "secondary" protection to depositors, equalling the stock of the depositary bank, it should not be considered an evasion if the assets of the holding company are sufficient to satisfy that contingent liability on the bank shares held. Thus, where a holding company has a wide and diversified portfolio consisting of many strong operat- ing companies amply sufficient to satisfy any contingent liability on bank stock held, there should be no reason to hold its shareholders personally liable. And it is conceiv- able that a parent company, whose sole assets are stocks in a large number of sub- sidiary banks widely distributed geographically, would be adequately financed to pro- tect creditors of failing banks by converting some of the stocks of their solvent banks into cash.