Vania Is Especi

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Extent to Which the Common Law Is Applied in Determining What

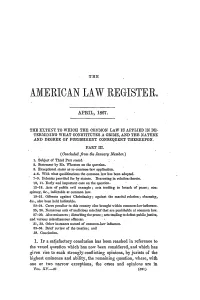

THE AMERICAN LAW REGISTER, APRIL, 1867. THE EXTE'N"IT TO WHICH THE COM ON LAW IS APPLIED IN DE- TERMINING WHAT CONSTITUTES A CRIME, AND THE NATURE AND DEGREE OF PUNISHMENT CONSEQUENT THEREUPON. PART III. (Concluded from the January.umber.) 1. Subject of Third. Part stated. 2. Statement by .Mr. Wheaton on tie question. 3. Exceptional states as to common-law application. 4-6. With what qualifications the common law has been adopted. 7-9. Felonies provided for by statute. Reasoning in relation thereto. 10, 11. Early and important case on the question. 12-18. Acts of public evil example; acts tending to breach of peace; con- -piracy, &c., indictable at common law. 19-21. Offences against Christianity; against the marital relation; obscenity, &c., also been held indictable. 22-24. Cases peculiar to this country also brought within common-law influence. 25, 26. 'Numerous acts of malicious mischief that are punishable at common law. 27-30. Also nuisances ; disturbing the peace; acts tenxding to defeat public justice. and various miscellaneous offences. 31, 32. Other instances named of common-law influence. 33-36. Brief review of the treatise; and 38. Conclusion. 1. IF a satisfactory conclusion has been reached in reference to the vexed question which has now been considered, and which has given rise to such strongly-conflicting opinions, by jurists of the highest eminence and ability, the remaining question, where, with one or two narrow exceptions, the eases and opinions are in VOL. XV.-21 (321) APPLICATION OF THE COMMON LAW almost perfect accord, cannot be attended with much difficulty. -

Abolishing the Crime of Public Nuisance and Modernising That of Public Indecency

International Law Research; Vol. 6, No. 1; 2017 ISSN 1927-5234 E-ISSN 1927-5242 Published by Canadian Center of Science and Education Abolishing the Crime of Public Nuisance and Modernising That of Public Indecency Graham McBain1,2 1 Peterhouse, Cambridge, UK 2 Harvard Law School, USA Correspondence: Graham McBain, 21 Millmead Terrace, Guildford, Surrey GU2 4AT, UK. E-mail: [email protected] Received: November 20, 2016 Accepted: February 19, 2017 Online Published: March 7, 2017 doi:10.5539/ilr.v6n1p1 URL: https://doi.org/10.5539/ilr.v6n1p1 1. INTRODUCTION Prior articles have asserted that English criminal law is very fragmented and that a considerable amount of the older law - especially the common law - is badly out of date.1 The purpose of this article is to consider the crime of public nuisance (also called common nuisance), a common law crime. The word 'nuisance' derives from the old french 'nuisance' or 'nusance' 2 and the latin, nocumentum.3 The basic meaning of the word is that of 'annoyance';4 In medieval English, the word 'common' comes from the word 'commune' which, itself, derives from the latin 'communa' - being a commonality, a group of people, a corporation.5 In 1191, the City of London (the 'City') became a commune. Thereafter, it is usual to find references with that term - such as common carrier, common highway, common council, common scold, common prostitute etc;6 The reference to 'common' designated things available to the general public as opposed to the individual. For example, the common carrier, common farrier and common innkeeper exercised a public employment and not just a private one. -

Quakers & Capitalism — Introduction

Quakers and Capitalism Introduction to the book Quakers and Capitalism by Steven Davison Who would you say is the second most famous Quaker? I am assuming that William Penn is the first most famous Quaker, and that Richard Nixon does not qualify as a Friend, despite his nominal membership. In the United States, it might be Herbert Hoover. He’s certainly famous enough. Problem is, so few people know he was an active Friend all his life. The answer, I propose, is John Bellers. A prominent British Friend around the turn of the 18th century, Bellers was well known to his contemporaries. Yet you would join an overwhelming majority of modern American Quakers if you have never heard of this man. So why do I say he’s the second most well known Friend in world history? Because some of his essays were required reading in Soviet schools throughout the Soviet period in the former Soviet Union—tens of millions of Russians have known who he is. Because he impressed Karl Marx and Friederich Engels so much that Das Kapital mentions him by name. Here is a man who enjoyed the fullest respect of his own generation, who possessed a deep, compassionate heart and a creative and far-ranging mind, who brought these faculties to bear on the problems of his own time in searching moral critique and bold proposals for pragmatic solutions to the problems he so clearly defined—in some cases for the first time. With equal measures of insight and foresight, Bellers wrote about economics and the plight of the worker, medical research and education, international politics and domestic social policy. -

The Gendered Nature of Quaker Charity

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Undergraduate Humanities Forum 2013-2014: Penn Humanities Forum Undergraduate Violence Research Fellows 5-2014 The Gendered Nature of Quaker Charity Panarat Anamwathana University of Pennsylvania Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/uhf_2014 Part of the History of Religion Commons Anamwathana, Panarat, "The Gendered Nature of Quaker Charity" (2014). Undergraduate Humanities Forum 2013-2014: Violence. 11. https://repository.upenn.edu/uhf_2014/11 This paper was part of the 2013-2014 Penn Humanities Forum on Violence. Find out more at http://www.phf.upenn.edu/annual-topics/violence. This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/uhf_2014/11 For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Gendered Nature of Quaker Charity Abstract For a holistic understanding of violence, the study of its antithesis, nonviolence, is necessary. A primary example of nonviolence is charity. Not only does charity prevent violence from rogue vagrants, but it also is an act of kindness. In seventeenth-century England, when a third of the population lived below the poverty line, charity was crucial. Especially successful were Quaker charity communities and the early involvement of Quaker women in administering aid. This is remarkable, considering that most parish- appointed overseers of the poor were usually male. What explains this phenomenon that women became the main administrators of Quaker charity? Filling in this gap of knowledge would shed further light on Quaker gender dynamics and the Quaker values that are still found in American culture today. Keywords Quakers, charity Disciplines History of Religion Comments This paper was part of the 2013-2014 Penn Humanities Forum on Violence. -

Old-Time Punishments

Presented to the UNIVERSITY OF TORONTO LIBRARY by the ONTARIO LEGISLATIVE LIBRARY 1980 (\V\ 7- OLD-TIME PUNISHMENTS. WORKS BY WILLIAM ANDREWS, F.R.H.S. Mr. William Andrews has produced several books of singular value in their historical and archaeological character. He has a genius for digging among dusty parchments and old books, and for bringing out from among them that which it is likely the public of to-day will care to read. Scotsman. Curiosities of the Church. A volume both entertaining and instructive, throwing much light on the manners and customs of bygone generations of Churchmen, and will be read to-day with much interest. Nftitbery House Magazine. An extremely interesting volume. North British Daily Mail. A work of lasting interest. Hull Kxaminer. Full of interest. The Globe. The reader will find much in this book to interest, instruct, and amuse. Home Chimes. We feel sure that many will feel grateful to Mr. Andrews for having produced such an interesting book. The Antiquary. Historic Yorkshire. Cuthbert Bede, the popular author of "Verdant Green," writing to Society, says: "Historic Yorkshire," by William Andrews, will be of great interest and value to everyone connected with England's largest county. Mr. Andrews not only writes with due enthusiasm for his subject, but has arranged and marshalled his facts and figures with great skill, and produced a thoroughly popular work that will be read eagerly and with advantage. Historic Romance. STRANGE STORIES, CHARACTERS, SCENES, MYSTERIES, AND MEMORABLE EVENTS IN THE HISTORY OF OLD ENGLAND. In his present work Mr. Andrews has traversed a wider field than in his last book, "Historic Yorkshire," but it is marked by the same painstaking care for accuracy, and also by the pleasant way in which he popularises strange stories and out-of-the-way scenes in English History. -

Unusual Punishments” in Anglo- American Law: the Ed Ath Penalty As Arbitrary, Discriminatory, and Cruel and Unusual John D

Northwestern Journal of Law & Social Policy Volume 13 | Issue 4 Article 2 Spring 2018 The onceptC of “Unusual Punishments” in Anglo- American Law: The eD ath Penalty as Arbitrary, Discriminatory, and Cruel and Unusual John D. Bessler Recommended Citation John D. Bessler, The Concept of “Unusual Punishments” in Anglo-American Law: The Death Penalty as Arbitrary, Discriminatory, and Cruel and Unusual, 13 Nw. J. L. & Soc. Pol'y. 307 (2018). https://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/njlsp/vol13/iss4/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Northwestern Pritzker School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Northwestern Journal of Law & Social Policy by an authorized editor of Northwestern Pritzker School of Law Scholarly Commons. Copyright 2018 by Northwestern University Pritzker School of Law `Vol. 13, Issue 4 (2018) Northwestern Journal of Law and Social Policy The Concept of “Unusual Punishments” in Anglo-American Law: The Death Penalty as Arbitrary, Discriminatory, and Cruel and Unusual John D. Bessler* ABSTRACT The Eighth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution, like the English Bill of Rights before it, safeguards against the infliction of “cruel and unusual punishments.” To better understand the meaning of that provision, this Article explores the concept of “unusual punishments” and its opposite, “usual punishments.” In particular, this Article traces the use of the “usual” and “unusual” punishments terminology in Anglo-American sources to shed new light on the Eighth Amendment’s Cruel and Unusual Punishments Clause. The Article surveys historical references to “usual” and “unusual” punishments in early English and American texts, then analyzes the development of American constitutional law as it relates to the dividing line between “usual” and “unusual” punishments. -

Pennsylvania Magazine of HISTORY and BIOGRAPHY

THE Pennsylvania Magazine OF HISTORY AND BIOGRAPHY The Proprietors of the Province of West New Jersey, 1674-1702 OTH West New Jersey and East New Jersey were uneasy proprietary colonies because of the uncertainty respecting B their rights of government. Indeed, in 1702 they were forced to surrender their proprietary status, and were reunited under royal control. The establishment of West New Jersey, however, is of his- torical importance as a concerted effort of the Friends to create a self-contained Quaker colony in America some years before the founding of Pennsylvania. The grand strategy of the Society of Friends, which reached its apex in 1681-1682 with the planting of Pennsylvania and the purchase of East Jersey, cannot be compre- hended without the knowledge afforded by the West Jersey experi- ment. If all had succeeded, the Quakers would have controlled a domain extending from New York to Maryland and westward to the Ohio. The historian of the Quaker colonies, however, has rested con- tent in his knowledge of such seeming disparate occurrences as George Fox's journey to the Delaware in 1672, Penn's service as a Byllynge Trustee in 1675, and his participation as a joint purchaser of East Jersey in 1682. Obviously, a reconstruction of the early history of the Quaker colonies is needed, and the key to our under- standing lies in the founding of West New Jersey, the first of these. The establishment of this colony was not only a major project of the 117 Il8 JOHN E. POMFRET April Friends, but it elicited the support of the most substantial of them in the north country, the Midlands, London and Middlesex, and the Dublin area of Ireland. -

Critics Duped by Reds' Propaganda WASHINGTON (AP) — Eagleton's Past Psychiatric Is Vietnam, and Nixon In- President Said

Court Challenge SEE STORY BELOW The Weather THEDAILY FINAL Partly cloudy today, mgn around 80. Fair tonight. Most- ) Red Bank, Freehold ~T~ ly sunny tomorrow and Sun- I Long Branch 1 day, little temperature EDITION change. 24 PAGES Momnoutli Comity's Outstanding Home Newspaper VOL.95 NO.24 RED BANK, NJ. FRIDAY, JULY 28,1972 TENCENTS ' McGann Voids Common-Scold By HALLIE SCHRAEGER "A man might be 'trouble- took a swipe a( New Jersey's carry a pocket edition of for his definition of a common Judge McGann commented S. A. 2A:85-1 purports to make some and angry' and, by his "catch-all" statute (N. J. S; Blackstone with him." scold: "a public nuisance to in a footnote that the specified criminal the common law of- FREEHOLD — Finding the 'brawling and wrangling A. 2A:85-1), which, he said, is Sir William Blackstone her neighborhood, for which penalty constitutes cruel and fense of being a common ancient common law charge among' his 'neighbors, break "all that the average person (1723-1780), the most famous, offense she may be indicted unusual punishment.) scold, it is void because of its of being a "common scold" the' peace, increase discord^ has to guide his conduct." of English jurists, was the au- and, if convicted, shall be sen- "To a die-hard male chau- vagueness and is con- outmoded, unconstitutionally and become a nuisance to the Judge McGann said that thor ofi "Commentaries on the tenced to be placed in a cer- vinist, the public utterances of stitutionally unenforceable," vague and discriminatory, Su- neighborhood,' yet he could statute tells the average per- Laws of England" (1775) still tain engine of correction a dedicated woman's liber- be said. -

John Bellers (1654–1725): ‘A Veritable Phenomenon in the History of Political Economy’

Digital Commons @ George Fox University Faculty Publications - College of Christian Studies College of Christian Studies 2019 John Bellers (1654–1725): ‘A Veritable Phenomenon in the History of Political Economy’ Paul N. Anderson Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/ccs Part of the Christianity Commons John Bellers (1654–1725): ‘A Veritable Phenomenon in the History of Political Economy’ Paul N. Anderson What sort of a person would be an inspiration to Karl Marx and a champion of free trade, an advocate of gainful employment and hard work, a herald of providing education and medical care for the poor while also seeing their labour as the greatest resources of the rich, a prophetic voice seeking to curb the ills of heavy drinking and the developing of worthy living quarters for workers, a challenger of dishonesty in public service and in Parliament while also calling for a unified state of Europe and Christian unity, an exhorter of Friends to spiritual discipline, anger management, and prayer while also disparaging corporal punishment, needless imprisonment, and the death penalty? Such a person is John Bellers (1654–1725), and as Vail Palmer points out, only two leaders of Quakerism in the early years the movement are known beyond its religious appraisals: William Penn and John Bellers.1 Interestingly, however, the contribution of Bellers is better known among Marxist historians and socialism theorists than among students of Quakerism and religious history.2 While Bellers is covered in many textbooks on Marxism, his place in introductory Quaker texts is either absent or modest.3 Nonetheless, Bellers deserves a place as a leading 1T. -

Criminal Law Act 1967

Criminal Law Act 1967 CHAPTER 58 ARRANGEMENT OF SECTIONS PART I FELONY AND MISDEMEANOUR Section 1. Abolition of distinction between felony and misdemeanour. 2. Arrest without warrant. 3. Use of force in making arrest, etc. 4. Penalties for assisting offenders. 5. Penalties for concealing offences or giving false information. 6. Trial of offences. 7. Powers of dealing with offenders. 8. Jurisdiction of quarter sessions. 9. Pardon. 10. Amendments of particular enactments, and repeals. 11. Extent of Part I, and provision for Northern Ireland. 12. Commencement, savings, and other general provisions. PART II OBSOLETE CRIMES 13. Abolition of certain offences, and consequential repeals. PART III SUPPLEMENTARY 14. Civil rights in respect of maintenance and champerty. 15. Short title. SCHEDULES : Schedule 1-Lists of offences falling, or not falling, within jurisdiction of quarter sessions. Schedule 2-Supplementary amendments. Schedule 3-Repeals (general). Schedule 4--Repeals (obsolete crimes). A Criminal Law Act 1967 CH. 58 1 ELIZABETH II 1967 CHAPTER 58 An Act to amend the law of England and Wales by abolishing the division of crimes into felonies and misdemeanours and to amend and simplify the law in respect of matters arising from or related to that division or the abolition of it; to do away (within or without England and Wales) with certain obsolete crimes together with the torts of maintenance and champerty; and for purposes connected therewith. [21st July 1967] BE IT ENACTED by the Queen's most Excellent Majesty, by and with the advice and consent of the Lords Spiritual and Temporal, and Commons, in this present Parliament assembled, and by the authority of the same, as follows:- PART I FELONY AND MISDEMEANOUR 1.-(1) All distinctions between felony and misdemeanour are Abolition of abolished. -

Of the Friends' Historical Society

THE JOURNAL OF THE FRIENDS' HISTORICAL SOCIETY VOLUME FORTY-FOUR NUMBER TWO 1952 FRIENDS' HISTORICAL SOCIETY FRIENDS HOUSE, EUSTON ROAD, LONDON, N.W.I also obtainable at Friends Book Store 302 Arch Street, Philadelphia 6, Pa, U.S.A. Price Yearly ios» The Journal of George Fox EDITED BY JOHN L. NICKALLS \ A new edition of George Fox's Journal, complete, newly edited from the original sources and previous editions, with spelling, punctuation and contractions modified to make a book easily read today and yet authentic. Perm's Life of Fox is included and Dr H. J. Cadbury has provided an epilogue. With an introduction by Dr Geoffrey Nuttall. 215. net CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS LONDON AND NEW YORK Contents PAGE Tercentenary Commemoration Notes 49 The Devotional Life of Early Friends. Beatrice Saxon t^ IV &1/V » • •• •• •• •• The Catholic Boys at Ackworth: from Letters before and after their time there. John Sturge Stephens 70 Early Marriage Certificates. Henry J. Cadbury 79 * Two Italian Reporters on Quakerism 82 Microfilms of Friends' Registers in Ireland 87 Recent Publications 88 Notes and Queries 99 Index to Vol. XLIV 104 Vol. XLIV No. 2 1952 THE JOURNAL OF THE FRIENDS' HISTORICAL SOCIETY Publishing Office: Friends House, Euston Road, London, N. W. i. Communications should be addressed to the Editor at Friends House. Tercentenary Commemoration Notes Presidential Address at Lancaster REDERICK B. TOLLES gave his Presidential address on The Atlantic Community of the Early Friends at FLancaster Meeting House on the evening of Wednesday, i3th August. Many visitors to the Tercentenary com memorations were present, and two smaller audiences in adjacent rooms heard the address relayed. -

Agenda and Papers for 7 October 2017 Meeting

Calling Letter . Yearly Meeting of the Religious Society of Friends (Quakers) in Britain To members of Meeting for Sufferings 10 September 2017 Dear Friends, Our next meeting will be at Friends Meeting House, 6, Mount Street, Manchester on Saturday 7th October, starting as usual at 10am – and almost all of you have already registered! Those representatives who are in Manchester on the Friday evening before are warmly invited to food and fellowship with local friends at the Meeting House from about 6pm to 8pm. There will be various displays there (on Friday and Saturday) about local Quaker work including Quaker Social Justice, LGBT/Pride, and Quaker Congo Partnership. There will be Friends present from each of the four local Area Meetings - Manchester and Warrington, Hardshaw and Mann, East Cheshire and Pendle Hill. However our meeting on Saturday will be in the usual format as you will see from the attached agenda. The key items this time are: receipt of various minutes consideration of the phrase ‘Quakers in Britain’ and of communication more generally consideration of Yearly Meeting Gathering 2017 (and in particular receipt and consideration of the minutes of Yearly Meeting) engagement with Quaker Peace and Social Witness Central Committee (QPSWCC). Information from the central committees enables us to learn directly from them about their discernment on issues relating to the nature of the work undertaken by Britain Yearly Meeting and enables us to respond directly to any queries, whilst furthering the work towards the vision encapsulated in ‘Our faith in the future’. Included in this mailing are the minutes from Meeting for Sufferings Arrangements Group and I draw your attention to the reflection on our last meeting.