516134 George Mason JLEP 8.3 R3.Ps

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Extent to Which the Common Law Is Applied in Determining What

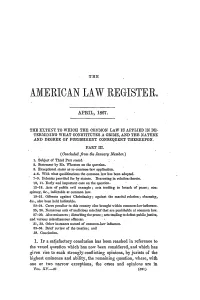

THE AMERICAN LAW REGISTER, APRIL, 1867. THE EXTE'N"IT TO WHICH THE COM ON LAW IS APPLIED IN DE- TERMINING WHAT CONSTITUTES A CRIME, AND THE NATURE AND DEGREE OF PUNISHMENT CONSEQUENT THEREUPON. PART III. (Concluded from the January.umber.) 1. Subject of Third. Part stated. 2. Statement by .Mr. Wheaton on tie question. 3. Exceptional states as to common-law application. 4-6. With what qualifications the common law has been adopted. 7-9. Felonies provided for by statute. Reasoning in relation thereto. 10, 11. Early and important case on the question. 12-18. Acts of public evil example; acts tending to breach of peace; con- -piracy, &c., indictable at common law. 19-21. Offences against Christianity; against the marital relation; obscenity, &c., also been held indictable. 22-24. Cases peculiar to this country also brought within common-law influence. 25, 26. 'Numerous acts of malicious mischief that are punishable at common law. 27-30. Also nuisances ; disturbing the peace; acts tenxding to defeat public justice. and various miscellaneous offences. 31, 32. Other instances named of common-law influence. 33-36. Brief review of the treatise; and 38. Conclusion. 1. IF a satisfactory conclusion has been reached in reference to the vexed question which has now been considered, and which has given rise to such strongly-conflicting opinions, by jurists of the highest eminence and ability, the remaining question, where, with one or two narrow exceptions, the eases and opinions are in VOL. XV.-21 (321) APPLICATION OF THE COMMON LAW almost perfect accord, cannot be attended with much difficulty. -

Vania Is Especi

THE PUNISHMENT OF CRIME IN PROVINCIAL PENNSYLVANIA HE history of the punishment of crime in provincial Pennsyl- vania is especially interesting, not only as one aspect of the Tbroad problem of the transference of English institutions to America, a phase of our development which for a time has achieved a somewhat dimmed significance in a nationalistic enthusiasm to find the conditioning influence of our development in that confusion and lawlessness of our own frontier, but also because of the influence of the Quakers in the development df our law. While the general pat- tern of the criminal law transferred from England to Pennsylvania did not differ from that of the other colonies, in that the law and the courts they evolved to administer the law, like the form of their cur- rency, their methods of farming, the games they played, were part of their English cultural heritage, the Quakers did arrive in the new land with a new concept of the end of the criminal law, and proceeded immediately to give force to this concept by statutory enactment.1 The result may be stated simply. At a time when the philosophy of Hobbes justified any punishment, however harsh, provided it effec- tively deterred the occurrence of a crime,2 when commentators on 1 Actually the Quakers voiced some of their views on punishment before leaving for America in the Laws agreed upon in England, wherein it was provided that all pleadings and process should be short and in English; that prisons should be workhouses and free; that felons unable to make satisfaction should become bond-men and work off the penalty; that certain offences should be published with double satisfaction; that estates of capital offenders should be forfeited, one part to go to the next of kin of the victim and one part to the next of kin of the criminal; and that certain offences of a religious and moral nature should be severely punished. -

Abolishing the Crime of Public Nuisance and Modernising That of Public Indecency

International Law Research; Vol. 6, No. 1; 2017 ISSN 1927-5234 E-ISSN 1927-5242 Published by Canadian Center of Science and Education Abolishing the Crime of Public Nuisance and Modernising That of Public Indecency Graham McBain1,2 1 Peterhouse, Cambridge, UK 2 Harvard Law School, USA Correspondence: Graham McBain, 21 Millmead Terrace, Guildford, Surrey GU2 4AT, UK. E-mail: [email protected] Received: November 20, 2016 Accepted: February 19, 2017 Online Published: March 7, 2017 doi:10.5539/ilr.v6n1p1 URL: https://doi.org/10.5539/ilr.v6n1p1 1. INTRODUCTION Prior articles have asserted that English criminal law is very fragmented and that a considerable amount of the older law - especially the common law - is badly out of date.1 The purpose of this article is to consider the crime of public nuisance (also called common nuisance), a common law crime. The word 'nuisance' derives from the old french 'nuisance' or 'nusance' 2 and the latin, nocumentum.3 The basic meaning of the word is that of 'annoyance';4 In medieval English, the word 'common' comes from the word 'commune' which, itself, derives from the latin 'communa' - being a commonality, a group of people, a corporation.5 In 1191, the City of London (the 'City') became a commune. Thereafter, it is usual to find references with that term - such as common carrier, common highway, common council, common scold, common prostitute etc;6 The reference to 'common' designated things available to the general public as opposed to the individual. For example, the common carrier, common farrier and common innkeeper exercised a public employment and not just a private one. -

Litigation Funding: Status and Issues

Centre for Socio‐Legal Studies, Oxford Lincoln Law School LITIGATION FUNDING: STATUS AND ISSUES RESEARCH REPORT Christopher Hodges, John Peysner and Angus Nurse January 2012 sponsored by 1 Summary Litigation funding is new and topical. It has the capacity to significantly alter the litigation scene. It gives rise to particular issues that need understanding and attention. It is relevant only in certain situations, and while it is not a possible solution to all types of claims it has the potential to significantly increase opportunities to pursue certain claims. The basic model of litigation funding is an investment business based on securing an appropriate return on investment. It is not a banking loan as no interest is charged, and not insurance as no premium is charged. Investment is made in any case that has a sufficient prospect of success on its merits, and has a strong legal team with a convincing case strategy. In some types of offering, however, the model of litigation funding can appear to be more like the provision of legal services. This is where a funder, sometimes from a legal services background, conducts a detailed assessment of the legal merits of a case (including obtaining or providing specialist legal advice on the case) prior to agreeing to funding. Funders determine the risk, and ultimately the extent of the investment, based on an assessment of the merits of the case, the solvency of the defendant (or, in the case of a funded defendant, the resources of the claimant) and the size of the claim and likely return. However, during this research the contrary view that litigation funding is part of the legal services market has been raised. -

Old-Time Punishments

Presented to the UNIVERSITY OF TORONTO LIBRARY by the ONTARIO LEGISLATIVE LIBRARY 1980 (\V\ 7- OLD-TIME PUNISHMENTS. WORKS BY WILLIAM ANDREWS, F.R.H.S. Mr. William Andrews has produced several books of singular value in their historical and archaeological character. He has a genius for digging among dusty parchments and old books, and for bringing out from among them that which it is likely the public of to-day will care to read. Scotsman. Curiosities of the Church. A volume both entertaining and instructive, throwing much light on the manners and customs of bygone generations of Churchmen, and will be read to-day with much interest. Nftitbery House Magazine. An extremely interesting volume. North British Daily Mail. A work of lasting interest. Hull Kxaminer. Full of interest. The Globe. The reader will find much in this book to interest, instruct, and amuse. Home Chimes. We feel sure that many will feel grateful to Mr. Andrews for having produced such an interesting book. The Antiquary. Historic Yorkshire. Cuthbert Bede, the popular author of "Verdant Green," writing to Society, says: "Historic Yorkshire," by William Andrews, will be of great interest and value to everyone connected with England's largest county. Mr. Andrews not only writes with due enthusiasm for his subject, but has arranged and marshalled his facts and figures with great skill, and produced a thoroughly popular work that will be read eagerly and with advantage. Historic Romance. STRANGE STORIES, CHARACTERS, SCENES, MYSTERIES, AND MEMORABLE EVENTS IN THE HISTORY OF OLD ENGLAND. In his present work Mr. Andrews has traversed a wider field than in his last book, "Historic Yorkshire," but it is marked by the same painstaking care for accuracy, and also by the pleasant way in which he popularises strange stories and out-of-the-way scenes in English History. -

Heuristics, Biases, and Consumer Litigation Funding at the Bargaining Table

Heuristics, Biases, and Consumer Litigation Funding at the Bargaining Table I. INTRODUCTION .................................................................. 262 II. CURRENT LANDSCAPE OF CONSUMER LITIGATION FUNDING ........................................................................... 264 A. Snapshot of the Blooming Consumer-Litigation- Funding Business .................................................. 265 B. Consumer-Litigation-Funding Concerns ................ 267 1. Consumer-Protection Concerns ................... 267 2. Judicial-System Concerns ........................... 268 C. Judicial and Regulatory Responses ........................ 270 1. Responses to Consumer-Protection Concerns ..................................................... 271 2. Responses to Judicial-System Concerns ...... 273 III. CONSUMER LITIGATION FUNDING AND SETTLEMENT .......... 275 A. Standard Law-and-Economics Model of Settlement .......................................................... 278 B. Behavioral Law-and-Economics Framework for Settlement ......................................................... 280 1. From Optimistic to Overoptimistic: Litigation Funding and the Self-Serving Bias ............................................................. 281 2. Winner or Loser? Litigation Funding and Framing ...................................................... 284 IV. DEFLATING OVEROPTIMISM AND REFRAMING FAIR SETTLEMENT OFFERS ........................................................ 289 A. Pure Paternalism: Banning Litigation Funding ..... 290 B. System -

Unusual Punishments” in Anglo- American Law: the Ed Ath Penalty As Arbitrary, Discriminatory, and Cruel and Unusual John D

Northwestern Journal of Law & Social Policy Volume 13 | Issue 4 Article 2 Spring 2018 The onceptC of “Unusual Punishments” in Anglo- American Law: The eD ath Penalty as Arbitrary, Discriminatory, and Cruel and Unusual John D. Bessler Recommended Citation John D. Bessler, The Concept of “Unusual Punishments” in Anglo-American Law: The Death Penalty as Arbitrary, Discriminatory, and Cruel and Unusual, 13 Nw. J. L. & Soc. Pol'y. 307 (2018). https://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/njlsp/vol13/iss4/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Northwestern Pritzker School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Northwestern Journal of Law & Social Policy by an authorized editor of Northwestern Pritzker School of Law Scholarly Commons. Copyright 2018 by Northwestern University Pritzker School of Law `Vol. 13, Issue 4 (2018) Northwestern Journal of Law and Social Policy The Concept of “Unusual Punishments” in Anglo-American Law: The Death Penalty as Arbitrary, Discriminatory, and Cruel and Unusual John D. Bessler* ABSTRACT The Eighth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution, like the English Bill of Rights before it, safeguards against the infliction of “cruel and unusual punishments.” To better understand the meaning of that provision, this Article explores the concept of “unusual punishments” and its opposite, “usual punishments.” In particular, this Article traces the use of the “usual” and “unusual” punishments terminology in Anglo-American sources to shed new light on the Eighth Amendment’s Cruel and Unusual Punishments Clause. The Article surveys historical references to “usual” and “unusual” punishments in early English and American texts, then analyzes the development of American constitutional law as it relates to the dividing line between “usual” and “unusual” punishments. -

SUPREME COURT STATE of COLORADO 2 East 14Th Avenue Denver, CO 80203 on Certiorari to the Colorado Court of Appeals Hon

SUPREME COURT STATE OF COLORADO 2 East 14th Avenue Denver, CO 80203 On Certiorari to the Colorado Court of Appeals Hon. John D. Dailey, Steven L. Bernard, and Richard L. Gabriel, Judges, Case No. 2012CA1130 District Court, City and County of Denver Hon. Brian Whitney and Edward D. Bronfin, Judges, Case No. 2010CV8380 OASIS LEGAL FINANCE GROUP, LLC; OASIS LEGAL FINANCE, LLC; OASIS LEGAL FINANCE OPERATING COMPANY, LLC; and PLAINTIFF FUNDING HOLDING, INC., d/b/a LAWCASH, ♦ COURT USE ONLY A Petitioners, Case No. 2013SC0497 v. JOHN W. SUTHERS, in his capacity as Attorney General of the State of Colorado; and JULIE ANN MEADE, in her capacity as the Administrator, Uniform Consumer Credit Code, Respondents. David R. Fine, #16852 MCKENNA LONG & ALDRIDGE LLP 1400 Wewatta Street, Suite 700 Denver, Colorado 80202-5556 Tel: (303) 634-4000 Fax: (303) 634-4400 ATTORNEY FOR AMICI CURIAE CHAMBER OF COMMERCE OF THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA AND DENVER METRO CHAMBER OF COMMERCE ADDENDUM TOAMICI CURIAE BRIEF OF CHAMBER OF COMMERCE OF THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA AND THE DENVER METRO CHAMBER OF COMMERCE IN SUPPORT OF RESPONDENTS ADDENDUM EXHIBIT 1 Lawsuit FinancingFinancing Terms Terms and and Conditions Conditions I Oasis I Oasis Legal Legal Finance Finance Page 11 ofof 33 Oasis 1-877-333-6675 Legal Final/COFinance'. WELIVE CHAT 1 1=CHAT itall= Lawsuit fundingFunding Structured settlements Setttements Resources About Oasis Attorneys Site Search: : SEARCH Ver esteeste sitiositio en en espalloi espanol Select Language Language V Start YourYour FREEFREE ApplicationApplication Nowt Nowt Oasis Legal Legal Lawsuit Lawsuit Financing Financing Terms Terms and andConditions Conditions Al Fields are RewiredRequired FistFirst Name: Name: • Oasis specializesspecialzes inIn lawsuitlawsuit financing financing for for individual individual plaintiffs. -

Court of Appeals, State of Colorado

COURT OF APPEALS, STATE OF COLORADO Colorado State Judicial Building 2 East 14th Avenue Denver, Colorado 80203 Appeal from the Denver County District Court Honorable Edward D. Bronfin, District Court Judge Civil Action No. 10CV8380 Plaintiffs-Appellants: OASIS LEGAL FINANCE GROUP, LLC; OASIS LEGAL FINANCE, LLC; OASIS LEGAL FINANCE OPERATING COMPANY, LLC; and PLAINTIFF FUNDING HOLDING, INC., d/b/a LAWCASH, v. Defendants-Appellees: JOHN W. SUTHERS, in his capacity as Attorney General of the State of Colorado; and LAURA E. UDIS, in her capacity as the Administrator, Uniform Consumer Credit Code. COURT USE ONLY Attorneys for Plaintiffs-Appellants: Case Number: 12CA1130 Names: Jason R. Dunn, #33011 Karl L. Schock, #38239 Address: Brownstein Hyatt Farber Schreck LLP 410 Seventeenth Street, Suite 2200 Denver, Colorado 80202 Phone No.: (303) 223-1100 E-mail: jdunn @bhfs.com [email protected] APPELLANTS' OPENING BRIEF CERTIFICATE OF COMPLIANCE I hereby certify that this brief complies with all requirements of C.A.R. 28 and C.A.R. 32, including all formatting requirements set forth in these rules. Specifically, the undersigned certifies that: The brief complies with C.A.R. 28(g). Choose one: It contains 6,672 words. The brief complies with C.A.R. 28(k). X For the party raising the issue: It contains under a separate heading (1) a concise statement of the applicable standard of appellate review with citation to authority; and (2) a citation to the precise location in the record, not to an entire document, where the issue was raised and ruled on. s/ Jason R. Dunn Jason R. -

Reshaping Third-Party Funding

Washington and Lee University School of Law Washington & Lee University School of Law Scholarly Commons Scholarly Articles Faculty Scholarship 2-2017 Reshaping Third-Party Funding Victoria Sahani Washington and Lee University School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.wlu.edu/wlufac Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Victoria Shannon Sahani, Reshaping Third-Party Funding, 91 Tul. L. Rev. 405 (2017). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Washington & Lee University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Scholarly Articles by an authorized administrator of Washington & Lee University School of Law Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TULANE LAW REVIEW VOL. 91 FEBRUARY 2017 NO. 3 Reshaping Third-Party Funding Victoria Shannon Sahani* Third-party funding is a controversial business arrangement whereby an outside entity—called a third-party funder—finances the legal representation of a party involved in litigation or arbitration or finances a law firm’s portfolio of cases in return for a profit. * © 2017 Victoria Shannon Sahani. Associate Professor of Law, Washington and Lee University School of Law; J.D., Harvard Law School; A.B., Harvard University; coauthor of the book THIRD-PARTY FUNDING IN INTERNATIONAL ARBITRATION (forthcoming 2017) (with Lisa Bench Nieuwveld); member of the Third-Party Funding Task Force (http://www.arbitration-icca.org/projects/Third_Party_Funding.html); member of the Advisory Council of the Alliance for Responsible Consumer Legal Funding (ARC Legal Funding) (http://arclegalfunding.org/). The author would like to thank Catherine Rogers, Tony Sebok, Maya Steinitz, Jason Rantanen, Renee Jones, Nicola Sharpe, Shaun Shaughnessy, Margaret Hu, Brant Hellwig, Chris Drahozal, Angela Onwuachi-Willig, Tai- Heng Cheng, Jean Y. -

Critics Duped by Reds' Propaganda WASHINGTON (AP) — Eagleton's Past Psychiatric Is Vietnam, and Nixon In- President Said

Court Challenge SEE STORY BELOW The Weather THEDAILY FINAL Partly cloudy today, mgn around 80. Fair tonight. Most- ) Red Bank, Freehold ~T~ ly sunny tomorrow and Sun- I Long Branch 1 day, little temperature EDITION change. 24 PAGES Momnoutli Comity's Outstanding Home Newspaper VOL.95 NO.24 RED BANK, NJ. FRIDAY, JULY 28,1972 TENCENTS ' McGann Voids Common-Scold By HALLIE SCHRAEGER "A man might be 'trouble- took a swipe a( New Jersey's carry a pocket edition of for his definition of a common Judge McGann commented S. A. 2A:85-1 purports to make some and angry' and, by his "catch-all" statute (N. J. S; Blackstone with him." scold: "a public nuisance to in a footnote that the specified criminal the common law of- FREEHOLD — Finding the 'brawling and wrangling A. 2A:85-1), which, he said, is Sir William Blackstone her neighborhood, for which penalty constitutes cruel and fense of being a common ancient common law charge among' his 'neighbors, break "all that the average person (1723-1780), the most famous, offense she may be indicted unusual punishment.) scold, it is void because of its of being a "common scold" the' peace, increase discord^ has to guide his conduct." of English jurists, was the au- and, if convicted, shall be sen- "To a die-hard male chau- vagueness and is con- outmoded, unconstitutionally and become a nuisance to the Judge McGann said that thor ofi "Commentaries on the tenced to be placed in a cer- vinist, the public utterances of stitutionally unenforceable," vague and discriminatory, Su- neighborhood,' yet he could statute tells the average per- Laws of England" (1775) still tain engine of correction a dedicated woman's liber- be said. -

Criminal Law Act 1967

Criminal Law Act 1967 CHAPTER 58 ARRANGEMENT OF SECTIONS PART I FELONY AND MISDEMEANOUR Section 1. Abolition of distinction between felony and misdemeanour. 2. Arrest without warrant. 3. Use of force in making arrest, etc. 4. Penalties for assisting offenders. 5. Penalties for concealing offences or giving false information. 6. Trial of offences. 7. Powers of dealing with offenders. 8. Jurisdiction of quarter sessions. 9. Pardon. 10. Amendments of particular enactments, and repeals. 11. Extent of Part I, and provision for Northern Ireland. 12. Commencement, savings, and other general provisions. PART II OBSOLETE CRIMES 13. Abolition of certain offences, and consequential repeals. PART III SUPPLEMENTARY 14. Civil rights in respect of maintenance and champerty. 15. Short title. SCHEDULES : Schedule 1-Lists of offences falling, or not falling, within jurisdiction of quarter sessions. Schedule 2-Supplementary amendments. Schedule 3-Repeals (general). Schedule 4--Repeals (obsolete crimes). A Criminal Law Act 1967 CH. 58 1 ELIZABETH II 1967 CHAPTER 58 An Act to amend the law of England and Wales by abolishing the division of crimes into felonies and misdemeanours and to amend and simplify the law in respect of matters arising from or related to that division or the abolition of it; to do away (within or without England and Wales) with certain obsolete crimes together with the torts of maintenance and champerty; and for purposes connected therewith. [21st July 1967] BE IT ENACTED by the Queen's most Excellent Majesty, by and with the advice and consent of the Lords Spiritual and Temporal, and Commons, in this present Parliament assembled, and by the authority of the same, as follows:- PART I FELONY AND MISDEMEANOUR 1.-(1) All distinctions between felony and misdemeanour are Abolition of abolished.