Offences and Punishments Under the New Criminal Code

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Extent to Which the Common Law Is Applied in Determining What

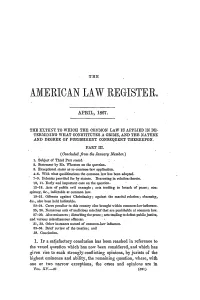

THE AMERICAN LAW REGISTER, APRIL, 1867. THE EXTE'N"IT TO WHICH THE COM ON LAW IS APPLIED IN DE- TERMINING WHAT CONSTITUTES A CRIME, AND THE NATURE AND DEGREE OF PUNISHMENT CONSEQUENT THEREUPON. PART III. (Concluded from the January.umber.) 1. Subject of Third. Part stated. 2. Statement by .Mr. Wheaton on tie question. 3. Exceptional states as to common-law application. 4-6. With what qualifications the common law has been adopted. 7-9. Felonies provided for by statute. Reasoning in relation thereto. 10, 11. Early and important case on the question. 12-18. Acts of public evil example; acts tending to breach of peace; con- -piracy, &c., indictable at common law. 19-21. Offences against Christianity; against the marital relation; obscenity, &c., also been held indictable. 22-24. Cases peculiar to this country also brought within common-law influence. 25, 26. 'Numerous acts of malicious mischief that are punishable at common law. 27-30. Also nuisances ; disturbing the peace; acts tenxding to defeat public justice. and various miscellaneous offences. 31, 32. Other instances named of common-law influence. 33-36. Brief review of the treatise; and 38. Conclusion. 1. IF a satisfactory conclusion has been reached in reference to the vexed question which has now been considered, and which has given rise to such strongly-conflicting opinions, by jurists of the highest eminence and ability, the remaining question, where, with one or two narrow exceptions, the eases and opinions are in VOL. XV.-21 (321) APPLICATION OF THE COMMON LAW almost perfect accord, cannot be attended with much difficulty. -

Imagereal Capture

Some Aspects of Theft of Computer Software by M. Dunning I. INTRODUCTION The purpose of this paper is to test the capability of New Zealand law to adequately deal with the impact that computers have on current notions of crimes relating to property. Has the criminal law kept pace with technology and continued to protect property interests or is our law flexible enough to be applied to new situations anyway? The increase of the moneyless society may mean a decrease in money motivated crimes of violence such as robbery, and an increase in white collar crime. Every aspect of life is being computerised-even our per sonality is on character files, with the attendant )ossibility of criminal breach of privacy. The problems confronted in this area are mostly definitional. While it may be easy to recognise morally opprobrious conduct, the object of such conduct may not be so easily categorised as criminal. A factor of this is a general lack of understanding of the computer process, so this would seem an appropriate place to begin the inquiry. II. THE COMPUTER Whiteside I identifies five key elements in a computer system. (1) Translation of data into a form readable by the computer, called input; and subject to manipulation by the introduction of false data. Remote terminals can be situated anywhere outside the cen tral processing unit (CPU), connected by (usually) telephone wires over which data may be transmitted, e.g. New Zealand banks on line to Databank. Outside users are given a site code number (identifying them) and an access code number (enabling entry to the CPU) which "plug" their remote terminal in. -

Common Law Fraud Liability to Account for It to the Owner

FRAUD FACTS Issue 17 March 2014 (3rd edition) INFORMATION FOR ORGANISATIONS Fraud in Scotland Fraud does not respect boundaries. Fraudsters use the same tactics and deceptions, and cause the same harm throughout the UK. However, the way in which the crimes are defined, investigated and prosecuted can depend on whether the fraud took place in Scotland or England and Wales. Therefore it is important for Scottish and UK-wide businesses to understand the differences that exist. What is a ‘Scottish fraud’? Embezzlement Overview of enforcement Embezzlement is the felonious appropriation This factsheet focuses on criminal fraud. There are many interested parties involved in of property without the consent of the owner In Scotland criminal fraud is mainly dealt the detection, investigation and prosecution with under the common law and a number where the appropriation is by a person who of statutory offences. The main fraud offences has received a limited ownership of the of fraud in Scotland, including: in Scotland are: property, subject to restoration at a future • Police Service of Scotland time, or possession of property subject to • common law fraud liability to account for it to the owner. • Financial Conduct Authority • uttering There is an element of breach of trust in • Trading Standards • embezzlement embezzlement making it more serious than • Department for Work and Pensions • statutory frauds. simple theft. In most cases embezzlement involves the appropriation of money. • Crown Office and Procurator Fiscal Service. It is important to note that the Fraud Act 2006 does not apply in Scotland (apart from Statutory frauds s10(1) which increases the maximum In addition there are a wide range of statutory Investigating fraud custodial sentence for fraudulent trading to offences which are closely related to the 10 years). -

Vania Is Especi

THE PUNISHMENT OF CRIME IN PROVINCIAL PENNSYLVANIA HE history of the punishment of crime in provincial Pennsyl- vania is especially interesting, not only as one aspect of the Tbroad problem of the transference of English institutions to America, a phase of our development which for a time has achieved a somewhat dimmed significance in a nationalistic enthusiasm to find the conditioning influence of our development in that confusion and lawlessness of our own frontier, but also because of the influence of the Quakers in the development df our law. While the general pat- tern of the criminal law transferred from England to Pennsylvania did not differ from that of the other colonies, in that the law and the courts they evolved to administer the law, like the form of their cur- rency, their methods of farming, the games they played, were part of their English cultural heritage, the Quakers did arrive in the new land with a new concept of the end of the criminal law, and proceeded immediately to give force to this concept by statutory enactment.1 The result may be stated simply. At a time when the philosophy of Hobbes justified any punishment, however harsh, provided it effec- tively deterred the occurrence of a crime,2 when commentators on 1 Actually the Quakers voiced some of their views on punishment before leaving for America in the Laws agreed upon in England, wherein it was provided that all pleadings and process should be short and in English; that prisons should be workhouses and free; that felons unable to make satisfaction should become bond-men and work off the penalty; that certain offences should be published with double satisfaction; that estates of capital offenders should be forfeited, one part to go to the next of kin of the victim and one part to the next of kin of the criminal; and that certain offences of a religious and moral nature should be severely punished. -

Criminal Code - General Remarks

-.=a;.t II it If you have issues viewing or accessing this file contact us at NCJRS.gov. U.S. Departrrent of Justice National Institute of Justice This document has been reproduced exactly as received from the person or organization originating it. Points of view or opinions stated in this document are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position or policies of the National Institute of Justice. Permission to reproduce this clilfl'~~G material has been granted by Public Domain/NIJ US Department of Justice to the National Criminal Justice Reference Service (NCJRS). Further reproduction outside of the NCJRS system requires permis sion of the c~t owner. 'r 'T 'r -- T 'Y ., - • - , 'T .. • - • ISS .1. -.. ," 4.•• EXTRATERRITORIAL JURISDICTION U.S. Department of Justice National Institute of Justice This document has been reproduced exaclly as received from the person or organization originating it. Points of view or opinions stated in this document are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position or policies of the Nationat tnstltute of Justice. Permission to reproduce this copyrighted material has been granted by Law Reform Commission of Canada to the National Criminal Justice Reference Service (NCJRS). Further reproduction outside of the NCJRS system requires permis· sion of the copyright owner. Une edition fran<;aise de ce document de travail est disponible. Son titre est : LA JURIDICTION EXTRA-TERRITORIALE Available by mail free of charge from: Law Reform Commission of Canada 130 Albert St., 7th Floor Ottawa, Canada KIA OL6 or Suite 310 Montreal, Quebec H3B 2N2 ©Ministry of Supply and Services Canada Catalogue No. -

'Ite Offences Against the Person

OFFENCES AGAINST THE PERSON ’ITE OFFENCES AGAINST THE PERSON ACT ARRANGEMENT OF SECTIONS 1. short title. Homicide 2. Capitall murders. 3. Sentence of death. Sentence of death not to be passed on pregnant mmm. Procedure where woman convicted of capital offence alleges she is pregnant. 3~.Life imprisonment for non-capital murder. 3~.Provisions as to procedure and regarding repulted and multiple murders. 3c. Proyisions as to appeab in relation to repeated and multiple murders. 3~.Provisions as to procedure regarding two or more murders tried together. 4. Abolition of ‘‘ms~~emalice’’. 5. Persons suffering from diminished responsibility. 6. Provocation. 7. suicide pact. 8. Conspiring or soliciting to commit murder. 9. Manslaughter. 10. Exasable homicide. 11. Petit tnasm. 12. Provision for trial of certain cases of murder or manslaryhtcr. Attempts to Murder 13. Administering poison, or wounding with intent to murder. 14. Destroying or damaging building with intent to murder. 15. Setting 6re to ship, etc., with intent to murder. 16. Attempting to administer poison, etc.. with intent to murder. 17. By other means attempting to commit murder. htters Threatening to Murder 18. Letters threatening to murder. [The inclusion of thiu page is authorized by L.N. 42/1995] OFFENCES A CAINST THE PERSON Acts Causing or Tending to Cause Donger to rife, or Bodily Harm 19. Preventing person endeavouring to save his life in shipwreck. 20. Shooting or attempting to shoot or wounding with intent to do grievous bodily harm. 21. What shall be deemed loaded arms. 22. Unlawful wounding. 23. Attempting to choke, etc., in order to commit indictable offence. -

Chapter 8 Criminal Conduct Offences

Chapter 8 Criminal conduct offences Page Index 1-8-1 Introduction 1-8-2 Chapter structure 1-8-2 Transitional guidance 1-8-2 Criminal conduct - section 42 – Armed Forces Act 2006 1-8-5 Violence offences 1-8-6 Common assault and battery - section 39 Criminal Justice Act 1988 1-8-6 Assault occasioning actual bodily harm - section 47 Offences against the Persons Act 1861 1-8-11 Possession in public place of offensive weapon - section 1 Prevention of Crime Act 1953 1-8-15 Possession in public place of point or blade - section 139 Criminal Justice Act 1988 1-8-17 Dishonesty offences 1-8-20 Theft - section 1 Theft Act 1968 1-8-20 Taking a motor vehicle or other conveyance without authority - section 12 Theft Act 1968 1-8-25 Making off without payment - section 3 Theft Act 1978 1-8-29 Abstraction of electricity - section 13 Theft Act 1968 1-8-31 Dishonestly obtaining electronic communications services – section 125 Communications Act 2003 1-8-32 Possession or supply of apparatus which may be used for obtaining an electronic communications service - section 126 Communications Act 2003 1-8-34 Fraud - section 1 Fraud Act 2006 1-8-37 Dishonestly obtaining services - section 11 Fraud Act 2006 1-8-41 Miscellaneous offences 1-8-44 Unlawful possession of a controlled drug - section 5 Misuse of Drugs Act 1971 1-8-44 Criminal damage - section 1 Criminal Damage Act 1971 1-8-47 Interference with vehicles - section 9 Criminal Attempts Act 1981 1-8-51 Road traffic offences 1-8-53 Careless and inconsiderate driving - section 3 Road Traffic Act 1988 1-8-53 Driving -

Criminal Code 2003.Pmd 273 11/27/2004, 12:35 PM 274 No

273 No. 9 ] Criminal Code [2004. SAINT LUCIA ______ No. 9 of 2004 ARRANGEMENT OF SECTIONS CHAPTER ONE General Provisions PART I PRELIMINARY Section 1. Short title 2. Commencement 3. Application of Code 4. General construction of Code 5. Common law procedure to apply where necessary 6. Interpretation PART II JUSTIFICATIONS AND EXCUSES 7. Claim of right 8. Consent by deceit or duress void 9. Consent void by incapacity 10. Consent by mistake of fact 11. Consent by exercise of undue authority 12. Consent by person in authority not given in good faith 13. Exercise of authority 14. Explanation of authority 15. Invalid consent not prejudicial 16. Extent of justification 17. Consent to fight cannot justify harm 18. Consent to killing unjustifiable 19. Consent to harm or wound 20. Medical or surgical treatment must be proper 21. Medical or surgical or other force to minors or others in custody 22. Use of force, where person unable to consent 23. Revocation annuls consent 24. Ignorance or mistake of fact criminal code 2003.pmd 273 11/27/2004, 12:35 PM 274 No. 9 ] Criminal Code [2004. 25. Ignorance of law no excuse 26. Age of criminal responsibility 27. Presumption of mental disorder 28. Intoxication, when an excuse 29. Aider may justify same force as person aided 30. Arrest with or without process for crime 31. Arrest, etc., other than for indictable offence 32. Bona fide assistant and correctional officer 33. Bona fide execution of defective warrant or process 34. Reasonable use of force in self-defence 35. Defence of property, possession of right 36. -

Archived Content Contenu Archivé

ARCHIVED - Archiving Content ARCHIVÉE - Contenu archivé Archived Content Contenu archivé Information identified as archived is provided for L’information dont il est indiqué qu’elle est archivée reference, research or recordkeeping purposes. It est fournie à des fins de référence, de recherche is not subject to the Government of Canada Web ou de tenue de documents. Elle n’est pas Standards and has not been altered or updated assujettie aux normes Web du gouvernement du since it was archived. Please contact us to request Canada et elle n’a pas été modifiée ou mise à jour a format other than those available. depuis son archivage. Pour obtenir cette information dans un autre format, veuillez communiquer avec nous. This document is archival in nature and is intended Le présent document a une valeur archivistique et for those who wish to consult archival documents fait partie des documents d’archives rendus made available from the collection of Public Safety disponibles par Sécurité publique Canada à ceux Canada. qui souhaitent consulter ces documents issus de sa collection. Some of these documents are available in only one official language. Translation, to be provided Certains de ces documents ne sont disponibles by Public Safety Canada, is available upon que dans une langue officielle. Sécurité publique request. Canada fournira une traduction sur demande. HISTORY OF THE LAW FOR JUVENILE DELINQUENTS No. 1984-56 Ministry of the Solicitor General of Canada Secretariat Copyright of this document does not belong to the Cffln. Proper authorization must be obtained from the author fa any intended use. Les droits d'auteur du présent document n'appartiennent pas à i'État. -

Canadian Criminal Law

Syllabus Canadian Criminal Law (Revised November 2020) Candidates are advised that the syllabus may be updated from time-to-time without prior notice. Candidates are responsible for obtaining the most current syllabus available. World Exchange Plaza 1810 - 45 O'Connor Street Ottawa Ontario K1P 1A4 Tel: (613) 236-1700 Fax: (613) 236-7233 www.flsc.ca Canadian Criminal Law EXAMINATION The function of the NCA exams is to determine whether applicants demonstrate a passable facility in the examined subject area to enable them to engage competently in the practice of law in Canada. To pass the examination candidates are expected to identify the relevant issues, select and identify the material rules of law including those in the Criminal Code of Canada and the relevant case law as understood in Canada, and explain how the law applies on each of the relevant issues, given the facts presented. Those who fail to identify key issues, or who demonstrate confusion on core legal concepts, or who merely list the issues and describe legal rules or who simply assert conclusions without demonstrating how those legal rules apply given the facts of the case will not succeed, as those are the skills being examined. The knowledge, skills and abilities examined in NCA exams are basically those that a competent lawyer in practice in Canada would be expected to possess. MATERIALS Required: • Steve Coughlan, Criminal Procedure, 4th ed. (Toronto: Irwin Law, 2020) • Kent Roach, Criminal Law, 7th ed. (Toronto: Irwin Law, 2018) • The most up-to-date Criminal Code (an annotated Criminal Code is highly recommended). -

Criminal Code

Criminal Code Warning: this is not an official translation. Under all circumstances the original text in Dutch language of the Criminal Code (Wetboek van Strafrecht) prevails. The State accepts no liability for damage of any kind resulting from the use of this translation. Criminal Code (Text valid on: 01-10-2012) Act of 3 March 1881 We WILLEM III, by the grace of God, King of the Netherlands, Prince of Orange-Nassau, Grand Duke of Luxemburg etc. etc. etc. Greetings to all who shall see or hear these presents! Be it known: Whereas We have considered that it is necessary to enact a new Criminal Code; We therefore, having heard the Council of State, and in consultation with the States General, have approved and decreed as We hereby approve and decree, to establish the following provisions which shall constitute the Criminal Code: Book One. General Provisions Part I. Scope of Application of Criminal Law Section 1 1. No act or omission which did not constitute a criminal offence under the law at the time of its commission shall be punishable by law. 2. Where the statutory provisions in force at the time when the criminal offence was committed are later amended, the provisions most favourable to the suspect or the defendant shall apply. Section 2 The criminal law of the Netherlands shall apply to any person who commits a criminal offence in the Netherlands. Section 3 The criminal law of the Netherlands shall apply to any person who commits a criminal offence on board a Dutch vessel or aircraft outside the territory of the Netherlands. -

FORFEITED Civil Forfeiture and the Canadian Constitution

FORFEITED Civil Forfeiture and the Canadian Constitution by Joshua Alan Krane A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Master of Laws Graduate Department of the Faculty of Law University of Toronto © Copyright by Joshua Alan Krane (2010) FORFEITED Civil Forfeiture and the Canadian Constitution Joshua Alan Krane, B.Soc.Sc., B.C.L/LL.B. Master of Laws Faculty of Law University of Toronto 2010 Abstract The enactment of civil asset forfeiture legislation by Alberta and Ontario in the fall of 2001, followed by the passage of similar legislation in five other provinces, has signalled a dramatic change in the way Canadian constitutional law ought to be understood. This thesis builds on American legal scholarship by highlighting how deficiencies in Canada’s constitutional law could create space for more inva- sive civil forfeiture statutes. Following a historical overview of forfeiture law in Canada, the thesis (i) examines how the Supreme Court of Canada mischaracter- ized this legislation as a matter of property and civil rights; (ii) considers whether the doctrine of federal paramountcy should have rendered the legislation inoper- able and the consequences of the failure by the Court to do so; and (iii) evaluates -ii- the impact of the absence of an entrenched property right in the constitution, in regard to this matter. -iii- Table of Contents INTRODUCTION................................................................................................. 1 The Aim of this Project..............................................................................