The Theme of Social Decay in the Last Five Novels of James Fenimore Cooper

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

James Fenimore Cooper 1St Edition Pdf Free Download

JAMES FENIMORE COOPER 1ST EDITION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Wayne Franklin | 9780300229103 | | | | | James Fenimore Cooper 1st edition PDF Book Navy during that time. During his leisure time, Cooper would venture through the forests of New York state and explore the shores of Lake Ontario. No Steamboats. I dampstained, bottom inch of Vol. American US. The novel's setting on Otsego Lake in central, upstate New York, is the same as that of The Pioneers , the first of the Leatherstocking Tales to be published Sort: Best Match. This name became a symbol of exciting adventures among Russian readers. All Auction Buy It Now. John Murray Following on a swell of popularity, Cooper published The Pioneers , the first of the Leatherstocking series in Paris: M. Results Pagination - Page 1 1 2 3 4. Carey and I. Seneca Lake in New York, political satire based on folklore. Works by James Fenimore Cooper. Appleton and Company, NY, Sep 30, PDT. Harvard University Press. Free Shipping. Fine Binding. Illustrated By N. It became the first novel written by an American to become a bestseller at home and abroad, requiring several re- printings to satisfy demand. A Tale of the Colony. All books mailed with Delivery Confirmation. March 1, The Deerslayer is considered to be the prequel to the rest of the series. The Water Witch or the Skimmer of the Seas. Published by popular library, Sellers declare the item's customs value and must comply with customs declaration laws. BAL James Fenimore Cooper 1st edition Writer Ended: Sep 30, PDT. Thank you for your understanding. History of the Navy of the United States of America. -

James Fenimore Cooper and the Genteel Hero of Romance

INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., was part of the material being photographed the photographer followed a definite method in "sectioning" the material. It is customary to begin photoing at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue photoing from left to right in equal sections with a small overlap. If necessary, sectioning is continued again — beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. The majority of users indicate that the textual content is of greatest value, however, a somewhat higher quality reproduction could be made from "photographs" if essential to the understanding of the dissertation. -

The Link to James Fenimore Cooper?

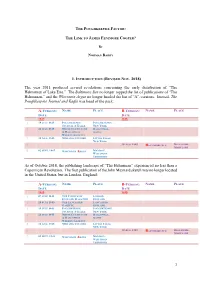

THE POUGHKEEPSIE FACTOR: THE LINK TO JAMES FENIMORE COOPER? BY NORMAN BARRY I. INTRODUCTION (REVISED NOV. 2018) The year 2011 produced several revelations concerning the early distribution of “The Helmsman of Lake Erie.” The Baltimore Sun no longer topped the list of publications of “The Helmsman,” and the Wisconsin Argus no longer headed the list of “A”-versions. Instead, The Poughkeepsie Journal and Eagle was head of the pack: A-VERSION: NAME PLACE B-VERSION: NAME PLACE DATE DATE 1845: 1845: 1 19 JULY 1845 POUGHKEEPSIE POUGHKEEPSIE, JOURNAL & EAGLE NEW YORK 2 26 JULY 1845 MAINE CULTIVATOR HALLOWELL, & HALLOWELL MAINE WEEKLY GAZETTE 3 14 AUG. 1845 MOHAWK COURIER LITTLE FALLS, NEW YORK 4 30 AUG. 1845 BALTIMORE SUN BALTIMORE, MARYLAND 02 SEPT. 1845 MADISON, 5 WISCONSIN ARGUS WISCONSIN TERRITORY As of October 2018, the publishing landscape of “The Helmsman” experienced no less than a Copernican Revolution. The first publication of the John Maynard sketch was no longer located in the United States, but in London, England: A-VERSION: NAME PLACE B-VERSION: NAME PLACE DATE DATE 1845: 1845: 1 07 JUNE 1845 THE CHURCH OF LONDON, ENGLAND MAGAZINE ENGLAND 2 14 JUNE 1845 THE LANCASTER LANCASTER, GAZETTE ENGLAND 3 19 JULY 1845 POUGHKEEPSIE POUGHKEEPSIE, JOURNAL & EAGLE NEW YORK 4 26 JULY 1845 MAINE CULTIVATOR HALLOWELL, & HALLOWELL MAINE WEEKLY GAZETTE 5 14 AUG. 1845 MOHAWK COURIER LITTLE FALLS, NEW YORK 6 30 AUG. 1845 BALTIMORE SUN BALTIMORE, MARYLAND 02 SEPT. 1845 MADISON, 7 WISCONSIN ARGUS WISCONSIN TERRITORY 1 The discovery of The Church of England Magazine as the very first publication of “The Helmsman of Lake Erie” in no way diminishes the importance of Poughkeepsie as the first place of publication in the United States. -

Literary Intertexts in Jules Verne's Voyages Extraordinaires

DePauw University Scholarly and Creative Work from DePauw University Modern Languages Faculty publications Modern Languages 7-1996 Literary Intertexts in Jules Verne's Voyages Extraordinaires Arthur B. Evans DePauw University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.depauw.edu/mlang_facpubs Part of the French and Francophone Literature Commons Recommended Citation Arthur B. Evans. "Literary Intertexts in Jules Verne's Voyages Extraordinaires" Science Fiction Studies 23.2 (1996): 171-187. Available at: http://scholarship.depauw.edu/mlang_facpubs/12/ This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Modern Languages at Scholarly and Creative Work from DePauw University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Modern Languages Faculty publications by an authorized administrator of Scholarly and Creative Work from DePauw University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Voyages Extraordinaires DePauw University From the SelectedWorks of Arthur Bruce Evans July 1996 Literary Intertexts in Jules Verne's Voyages Extraordinaires Contact Start Your Own Notify Me Author SelectedWorks of New Work Available at: http://works.bepress.com/arthur_evans/14 LITERARY INTERTEXTS IN VERNE'S VOYAGES 171 Arthur B. Evans Literary Intertexts in Jules Verne's Voyages Extraordinaires Contrary to popular belief (in America, at least), Jules Verne was neither a scientist, nor an inventor, nor a geographer. He was a writer. During the 1850s, Verne was an aspiring young dramatist with a degree in law, a pas- sionate love for literature, and a job at the Paris stock market. He began his professional writing career by penning short articles on scientific and historical topics for the lucrative journal Musée des Familles in order to supplement his meager income. -

Cooper, James Feminore, Papers, 1792

American Antiquarian Society Manuscript Collections NAME OF COLLECTION : LOCATION : Cooper, James Fenimore, Papers, 1792-1884 Mss. boxes "C" Oversize mss. boxes "C" SIZE OF COLLECTION : 7 manuscript boxes; 1 oversize manuscript box SOURCES OF INFORMATION ON COLLECTION : The Letters and Journals of James Fenimore Cooper , ed. by James Franklin Beard. 6 vols. (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1960-1968). Robert E. Spiller and Philip C. Blackburn. A Descriptive Bibliography of the Writings of James Fenimore Cooper . (New York: Bowker, 1934) SOURCE OF COLLECTION : One letter, dated 25? February 1832 to Armand Carrel, was purchased from George S. MacManus Co., 1983. Two letters, dated 22 May 1826 and 7 July 1827, was purchased from Ximenes Books, 1986. One letter , bound into The Deerslayer , was purchased from Argonaut Books, 1987. The remainder of the collection was the gift of the Paul Fenimore Cooper, Jr. estate, 1990. COLLECTION DESCRIPTION : James Fenimore Cooper (1789-1851), the son of William Cooper (1754-1809) and Elizabeth Fenimore Cooper (1752-1817), was born in Burlington, N.J., but spent his youth at Otsego Hall in Cooperstown, N.Y., the home of his father. After an early education at the public school in Cooperstown and at the home of an Episcopal rector in Albany, he attended Yale University for three years. In 1806 he went to sea, receiving a commission as a navy midshipman in 1808. His marriage to Susan Augusta De Lancy (1792-1852) of Westchester County, N.Y., took place in 1811, when he also resigned from the navy. In the years immediately following their marriage, the Coopers lived in Mamaroneck, Cooperstown, Scarsdale (where he began writing), and New York, N.Y. -

Adirondack Chronology

An Adirondack Chronology by The Adirondack Research Library of the Association for the Protection of the Adirondacks Chronology Management Team Gary Chilson Professor of Environmental Studies Editor, The Adirondack Journal of Environmental Studies Paul Smith’s College of Arts and Sciences PO Box 265 Paul Smiths, NY 12970-0265 [email protected] Carl George Professor of Biology, Emeritus Department of Biology Union College Schenectady, NY 12308 [email protected] Richard Tucker Adirondack Research Library 897 St. David’s Lane Niskayuna, NY 12309 [email protected] Last revised and enlarged – 20 January (No. 43) www.protectadks.org Adirondack Research Library The Adirondack Chronology is a useful resource for researchers and all others interested in the Adirondacks. It is made available by the Adirondack Research Library (ARL) of the Association for the Protection of the Adirondacks. It is hoped that it may serve as a 'starter set' of basic information leading to more in-depth research. Can the ARL further serve your research needs? To find out, visit our web page, or even better, visit the ARL at the Center for the Forest Preserve, 897 St. David's Lane, Niskayuna, N.Y., 12309. The ARL houses one of the finest collections available of books and periodicals, manuscripts, maps, photographs, and private papers dealing with the Adirondacks. Its volunteers will gladly assist you in finding answers to your questions and locating materials and contacts for your research projects. Introduction Is a chronology of the Adirondacks really possible? -

Oak Openings

Oak Openings James Fenimore Cooper Oak Openings Table of Contents Oak Openings............................................................................................................................................................1 James Fenimore Cooper.................................................................................................................................1 PREFACE......................................................................................................................................................1 CHAPTER I...................................................................................................................................................3 CHAPTER II..................................................................................................................................................9 CHAPTER III..............................................................................................................................................18 CHAPTER IV..............................................................................................................................................26 CHAPTER V................................................................................................................................................33 CHAPTER VI..............................................................................................................................................41 CHAPTER VII.............................................................................................................................................48 -

Thomas Cole on Architecture

THOMAS COLE ON ARCHITECTURE: PICTURING THE GOTHIC by Rebecca Ayres Schwartz A dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the University of Delaware in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Art History Spring 2016 © 2016 Rebecca Ayres Schwartz All Rights Reserved THOMAS COLE ON ARCHITECTURE: PICTURING THE GOTHIC by Rebecca Ayres Schwartz Approved: ______________________________________________________________ Lawrence Nees, Ph.D. Chair of the Department of Art History Approved: ______________________________________________________________ George H. Watson, Ph.D. Dean of the College of Arts and Sciences Approved: ______________________________________________________________ Ann L. Ardis, Ph.D. Senior Vice Provost for Graduate and Professional Education I certify that I have read this dissertation and that in my opinion it meets the academic and professional standard required by the University as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Signed: _________________________________________________________________ Bernard L. Herman, Ph.D. Professor in charge of dissertation I certify that I have read this dissertation and that in my opinion it meets the academic and professional standard required by the University as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Signed: ________________________________________________________________ Wendy Bellion, Ph.D. Member of dissertation committee I certify that I have read this dissertation and that in my opinion it meets the academic and professional standard required by the University as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Signed: ________________________________________________________________ J. Ritchie Garrison, Ph.D. Member of dissertation committee I certify that I have read this dissertation and that in my opinion it meets the academic and professional standard required by the University as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. -

James Fenimore Cooper and the Invention of the Passing Novel

Geoffrey James Fenimore Cooper and the Sanborn Invention of the Passing Novel The trouble with racism, for James Fenimore Cooper, is that it is too subtle. “We will not enter upon any subtle deductions which involve national character, or national enterprise and aptitude for sea- service,” he writes in an 1821 essay. “We leave such nice dis- tinctions for greater ingenuity than we can pretend to.”1 In opposition to “theorists” who insist on “the inferiority of all . who [are] not white,” he declares that there is no such thing as “general national superiority.”2 In opposition to metaphysicians who “reason as subtly as they can about the races and colors,” he argues that the “moral tone” of one’s behavior “depend[s] more on the conventional feel- ing . got up through moral agencies, than on birth-place, origin, or colour.”3 In the case of whites and Indians in the trans- Mississippi West, he writes in The Prairie (1827), it would take a “curious investi- gation” to identify the “points of difference” by which they were “still to be distinguished . now that the two, in the revolutions of the world, were approximating in their habits, their residence and not a little in their characters.”4 But racism is, Cooper recognizes, subtle in another way as well. Thanks to the power of “self- love,” an “unquiet spirit which haunts us to the last,” no one is immune to “the vulgar prejudice of national superiority . one of the strongest of all the weaknesses of our very weak nature.”5 “It is possible,” writes Corny Littlepage in The Chain- bearer (1845), -

The Hollywood Indian Stereotype: the Cinematic Othering and Assimilation of Native Americans at the Turn of the 20Th Century

Angles New Perspectives on the Anglophone World 10 | 2020 Creating the Enemy The Hollywood Indian Stereotype: The Cinematic Othering and Assimilation of Native Americans at the Turn of the 20th Century Martin Berny Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/angles/331 DOI: 10.4000/angles.331 ISSN: 2274-2042 Publisher Société des Anglicistes de l'Enseignement Supérieur Electronic reference Martin Berny, « The Hollywood Indian Stereotype: The Cinematic Othering and Assimilation of Native Americans at the Turn of the 20th Century », Angles [Online], 10 | 2020, Online since 01 April 2020, connection on 21 December 2020. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/angles/331 ; DOI : https:// doi.org/10.4000/angles.331 This text was automatically generated on 21 December 2020. Angles est mise à disposition selon les termes de la Licence Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International. The Hollywood Indian Stereotype: The Cinematic Othering and Assimilation of N... 1 The Hollywood Indian Stereotype: The Cinematic Othering and Assimilation of Native Americans at the Turn of the 20th Century Martin Berny The Elaboration of a Double Stereotype 1 The representation of Native Americans in popular culture is to this day a matter of deep puzzlement. Images spread through literary works such as James Fenimore Cooper’s Leatherstocking Tales, the paintings of Frederic Remington — whose influence on John Ford’s Westerns should not be undervalued —, or mainstream Hollywood compose a contradictory profile. A binary depiction of the Native characters maintained itself through the emergence of the Western as a film genre: the more positive noble Indian and the bloodthirsty savage.1 This cleavage demonstrates the preconceived attitude of the norm towards the Natives — an attitude that shaped Hollywood and that the film industry eventually reinforced and supplemented. -

Camille R. La Bossiere Pop Conrad and Child's Play

Camille R. La Bossiere Pop Conrad and Child's Play: A Context for The Rover We are the creatures of our light literature more than generally suspected in a world which prides itself on being scientific and practical, and in possession of incontrovertible theories. - Conrad, Chance Behold the boy. - Conrad, "A Preface to Thomas Beer's Stephen Crane" I made play in this world of dust, with the sons of Adam for my play fellows. - Proverbs 8:31, as translated by David Jones in Epoch & Artist I In February 1921, the diplomat Alexis Saint-Leger Leger (who would come to sign his poems Saint-John Perse) wrote to Conrad from Beijing: "Je vous ecoute encore me reciter les premieres laisses des Jumblies d'Edward Lear, ou vous m'assuriez trouver '!'esprit des grandes aventures' plus que dans les meilleurs auteurs de mer, comme Melville" (Oeuvres completes 886; hereafter cited as 0).1 That encounter, remem bered from their long nightly conversations at the novelist's home in Kent 6 DALHOUSIE REVIEW some nine years before, had made a deep impression on a Perse then in his mid twenties. His letter to Andre Gide dated 7 December 1912 registers the force of the effect: "Si je pouvais me permettre jamais de citer mon plaisir ou mon gout, je ne recommanderais qu' [Edward] Lear, seul poete d'une race qui me semble la race meme poetique" (0 781)_2 The impression was to be a lasting one. In September 1947, shortly after the publication of his prose-poem Vents, with its reprise of the spirit animating Lear's crew of a sieve bound for the Western Sea and the Hills of the Chankly Bore,3 Perse recalled-for G. -

Sensibility in the Novels of James Fenimore Cooper

INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed h "Missing Pags(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., was part of the material being photographed the photographer followed a definite method in "sectioning" the material. It is customary to begin photoing at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue photoing from left to right in equal sections with a small overlap. If necessary, sectioning is continued again — beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. The majority of users indicate that the textual content is of greatest value, however, a somewhat higher quality reproduction could be made from "photographs" if essential to the understanding of the dissertation.