The Helmsman of Lake Erie” to Poughkeepsie; Or

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

James Fenimore Cooper and Thomas Cole Corie Dias

Undergraduate Review Volume 2 Article 18 2006 Painters of a Changing New World: James Fenimore Cooper and Thomas Cole Corie Dias Follow this and additional works at: http://vc.bridgew.edu/undergrad_rev Part of the American Art and Architecture Commons, Comparative Literature Commons, and the Literature in English, North America Commons Recommended Citation Dias, Corie (2006). Painters of a Changing New World: James Fenimore Cooper and Thomas Cole. Undergraduate Review, 2, 110-118. Available at: http://vc.bridgew.edu/undergrad_rev/vol2/iss1/18 This item is available as part of Virtual Commons, the open-access institutional repository of Bridgewater State University, Bridgewater, Massachusetts. Copyright © 2006 Corie Dias 110 Painters ofa Changing New World: James Fenimore Cooper and Thomas Cole BY CORlE DIAS Corie wrote this piece as part of her uthor James Fenimore Cooper and painter Thomas Cole both Honors thesis under the mentorship of Dr. observed man's progress west and both disapproved of the way Ann Brunjes. She plans on pursuing a career in which the settlers went about this expansion. They were not in the fine arts field, while also continuing against such progress. but both men disagreed with the harmful to produce her own artwork. way it was done, with the natural environment suffering irreversible harm. Had the pioneers gone about making their changes in a different way, Cooper and Cole seem to suggest, the new society could have been established without corrupting the environment and would not have been criticized by these artists; however, the settlers showed little or no regard for the natural state of this new land. -

American Civil Associations and the Growth of American Government: an Appraisal of Alexis De Tocqueville’S Democracy in America (1835-1840) Applied to Franklin D

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 2-2017 American Civil Associations and the Growth of American Government: An Appraisal of Alexis de Tocqueville’s Democracy in America (1835-1840) Applied to Franklin D. Roosevelt's New Deal and the Post-World War II Welfare State John P. Varacalli The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/1828 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] AMERICAN CIVIL ASSOCIATIONS AND THE GROWTH OF AMERICAN GOVERNMENT: AN APPRAISAL OF ALEXIS DE TOCQUEVILLE’S DEMOCRACY IN AMERICA (1835- 1840) APPLIED TO FRANKLIN D. ROOSEVELT’S NEW DEAL AND THE POST-WORLD WAR II WELFARE STATE by JOHN P. VARACALLI A master’s thesis submitted to the Graduate Program in Liberal Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts, The City University of New York 2017 © 2017 JOHN P. VARACALLI All Rights Reserved ii American Civil Associations and the Growth of American Government: An Appraisal of Alexis de Tocqueville’s Democracy in America (1835-1840) Applied to Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal and the Post World War II Welfare State by John P. Varacalli The manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Liberal Studies in satisfaction of the thesis requirement for the degree of Master of Arts ______________________ __________________________________________ Date David Gordon Thesis Advisor ______________________ __________________________________________ Date Elizabeth Macaulay-Lewis Acting Executive Officer THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii ABSTRACT American Civil Associations and the Growth of American Government: An Appraisal of Alexis de Tocqueville’s Democracy in America (1835-1840) Applied to Franklin D. -

James Fenimore Cooper and the Genteel Hero of Romance

INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., was part of the material being photographed the photographer followed a definite method in "sectioning" the material. It is customary to begin photoing at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue photoing from left to right in equal sections with a small overlap. If necessary, sectioning is continued again — beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. The majority of users indicate that the textual content is of greatest value, however, a somewhat higher quality reproduction could be made from "photographs" if essential to the understanding of the dissertation. -

James Fenimore Cooper's Frontier: the Pioneers As History Thomas Berson

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2004 James Fenimore Cooper's Frontier: The Pioneers as History Thomas Berson Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES JAMES FENIMORE COOPER’S FRONTIER: THE PIONEERS AS HISTORY By THOMAS BERSON A Thesis Submitted to the Progra In A erican and Florida Studies in partial fulfill ent of the require ents for the degree of Master of Arts Degree Awarded: Sum er Se ester, 2004 The members of the Committee approve the thesis of Thomas Berson defended on July 1, 2004. --------------------------- Frederick Davis Professor Directing Thesis ---------------------------- John Fenstermaker Committee Member ---------------------------- Ned Stuckey-French Committee Member Approved: ------------------------------ John Fenstermaker, Chair, Program in American and Florida Studies ------------------------------ Donald Foss, Dean, College of Arts and Sciences The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii For My Parents iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Special thanks to John Fenstermaker, who gave me the opportunity to come back to school and to teach and to Fritz Davis, who helped me find direction in my studies. Additional thanks to the aforementioned and also to Ned Stuckey-French for taking the time out of their summers to sit on the committee for this paper. iv TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract................................................................................................................ -

James Fenimore Cooper and the Idea of Environmental Conservation in the Leatherstocking Tales (1823-1841)

Ceisy Nita Wuntu — James Fenimore Cooper and the Idea of Environmental Conservation in the Leatherstocking Tales (1823-1841) JAMES FENIMORE COOPER AND THE IDEA OF ENVIRONMENTAL CONSERVATION IN THE LEATHERSTOCKING TALES (1823-1841) Ceisy Nita Wuntu IKIP Negeri Manado [email protected] Abstract The spirit to respect the rights of all living environment in literature that was found in the 1970s in William Rueckert’s works was considered as the emergence of the new criticism in literature, ecocriticism, which brought the efforts to trace the spirit in works of literature. Works arose after the 1840s written by Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry David Thoreau, and Margareth Fuller, the American transcendentalists, are considered to be the first works presenting the respect for the living environment as claimed by Peter Barry. James Fenimore Cooper’s reputation in American literary history appeared because of his role in leading American literature into its identity. Among his works, The Leatherstocking Tales mostly attracted European readers’ attention when he successfully applied American issues. The major issue in the work is the spirit of the immigrants to dominate flora, fauna and human beings as was experienced by the indigenous people. Applying ecocriticism theory in doing the analysis, it has been found that Cooper’s works particularly his The Leatherstocking Tales (1823-1841) present Cooper’s great concern for the sustainable life. He shows that compassion, respect, wisdom, and justice are the essential aspects in preserving nature that meet the main concern of ecocriticism and hence the works that preceded the transcendentalists’ work places themselves as the embryo of ecocriticism in America. -

The Deerslayer”, “The Pathfinder”, “The Last of the Mohicans”, “The Pioneers” and “The Prairie”

THE MOVING PIONEERS IN AMERICA ON THE NOVELS BY JAMES FENIMORE COOPER Sarlan Student at Post Graduate Program of Sebelas Maret University of Surakarta Riyatno Sekolah Tinggi Teknik Telematika [ST3] Telkom Purwokerto Abstract This research is an attempt to reveal the life of pioneers in America in Cooper’s novels “The Deerslayer”, “The Pathfinder”, “The Last of the Mohicans”, “The Pioneers” and “The Prairie”. There are two objectives of the research, namely the reasons why the pioneers move to the West and what things that they have to have in order to be successful in the West. Using literary sociology, the two objectives of the research are discussed in the five novels as the main sources and the criticisms and the social condition in America as the secondary sources. The result of the research shows that the pioneers in America have some reasons so that they move to the West. They want to have wide land to settle. Besides, they want to cultivate the land to fulfill their needs. Other pioneers have to move to the West because they have to defend the British territory. In order to be successful, the pioneers have to have the hard skills and soft skills. They have to be able to hunt the wild animals, to use weapons to defend their properties and themselves. They also have to have self reliance, hard work, spirit, and discipline as well as vigilance. Keywords: pioneer, the West, movement, settlement. INTRODUCTION coast of America, from Virginia whose land Since John Smith landed in America was good for agriculture and plantations until and set up a colony in Jamestown in the early the Massachusetts which was barren and 17th century, waves of displacement of the rocky. -

The Link to James Fenimore Cooper?

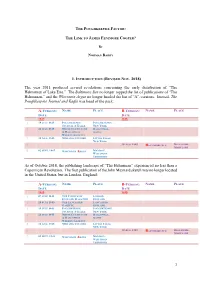

THE POUGHKEEPSIE FACTOR: THE LINK TO JAMES FENIMORE COOPER? BY NORMAN BARRY I. INTRODUCTION (REVISED NOV. 2018) The year 2011 produced several revelations concerning the early distribution of “The Helmsman of Lake Erie.” The Baltimore Sun no longer topped the list of publications of “The Helmsman,” and the Wisconsin Argus no longer headed the list of “A”-versions. Instead, The Poughkeepsie Journal and Eagle was head of the pack: A-VERSION: NAME PLACE B-VERSION: NAME PLACE DATE DATE 1845: 1845: 1 19 JULY 1845 POUGHKEEPSIE POUGHKEEPSIE, JOURNAL & EAGLE NEW YORK 2 26 JULY 1845 MAINE CULTIVATOR HALLOWELL, & HALLOWELL MAINE WEEKLY GAZETTE 3 14 AUG. 1845 MOHAWK COURIER LITTLE FALLS, NEW YORK 4 30 AUG. 1845 BALTIMORE SUN BALTIMORE, MARYLAND 02 SEPT. 1845 MADISON, 5 WISCONSIN ARGUS WISCONSIN TERRITORY As of October 2018, the publishing landscape of “The Helmsman” experienced no less than a Copernican Revolution. The first publication of the John Maynard sketch was no longer located in the United States, but in London, England: A-VERSION: NAME PLACE B-VERSION: NAME PLACE DATE DATE 1845: 1845: 1 07 JUNE 1845 THE CHURCH OF LONDON, ENGLAND MAGAZINE ENGLAND 2 14 JUNE 1845 THE LANCASTER LANCASTER, GAZETTE ENGLAND 3 19 JULY 1845 POUGHKEEPSIE POUGHKEEPSIE, JOURNAL & EAGLE NEW YORK 4 26 JULY 1845 MAINE CULTIVATOR HALLOWELL, & HALLOWELL MAINE WEEKLY GAZETTE 5 14 AUG. 1845 MOHAWK COURIER LITTLE FALLS, NEW YORK 6 30 AUG. 1845 BALTIMORE SUN BALTIMORE, MARYLAND 02 SEPT. 1845 MADISON, 7 WISCONSIN ARGUS WISCONSIN TERRITORY 1 The discovery of The Church of England Magazine as the very first publication of “The Helmsman of Lake Erie” in no way diminishes the importance of Poughkeepsie as the first place of publication in the United States. -

ANALYSIS the Prairie (1827) James Fenimore Cooper (1789-1851)

ANALYSIS The Prairie (1827) James Fenimore Cooper (1789-1851) The Prairie was Cooper’s favorite in his Leatherstocking series, he spent more time on it than on any other book in the Saga, it is the most rich and complex--his best--and it brings his vision into the closest relation to modern America, as in his concern for preserving the natural environment. This allegorical romance is the finale in the chronology of Natty Bumppo’s life, as he personifies the best spirit of the westward movement confronting the worst to come as represented by Ishmael Bush. The tone is elegiac, leading to the death of Leatherstocking. The book opens with a quotation from Shakespeare’s As You Like It that parallels Natty to Christ, implying a spiritual allegory and casting him as the pastoral “good shepherd”: “I pray thee, shepherd, if that love, or gold, / Can in this desert place buy entertainment, / Bring us where we may rest ourselves and feed.” Many critics such as Mark Twain and Bret Harte have ridiculed Cooper for not being a Realist, as if he could or should have had an entirely different education, life experience, sensibility and outlook--as if he could or should have ignored his own reality and his Victorian audience and written according to aesthetic principles that evolved and governed literary fiction long after his death. Cooper’s quotation from Shakespeare indicates that he is writing a romance, just as suggested by critic Leslie Fiedler: “In all [his] magic woods (sometimes more like those of Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night's Dream than any -

Rather Than Imposing Thematic Unity Or Predefining a Common Theoretical

Table of Contents Cooper‘s Pioneer: Breaking the Chain of Representation ......................... 1 Hans Löfgren ―‗Your stay must be a becoming‘: Ageing and Desire in J.M. Coetzee‘s Disgrace‖ ................................................................................................ 21 Billy Gray More than Murderers, Other than Men: Views of Masculinity in Modern Crime Fiction .......................................................................................... 39 Katarina Gregersdotter ―Ye Tories round the nation‖: An Analysis of Markers of Interactive- involved Discourse in Seventeenth Century Political Broadside Ballads ..................................................................................................... 59 Elisabetta Cecconi The Lingua Franca of Globalisation: ―filius nullius in terra nullius‖, as we say in English..................................................................................... 87 Martin A. Kayman Don‘t get me wrong! Negation in argumentative writing by Swedish and British students and professional writers............................................... 117 Jennifer Herriman Own and Possess―A Corpus Analysis ................................................. 141 Marie Nordlund Clausal order: A corpus-based experiment ........................................... 171 Göran Kjellmer † Trusty Trout, Humble Trout, Old Trout: A Curious Kettle ................... 191 William Sayers Cooper‘s Pioneer: Breaking the Chain of Representation Hans Löfgren, University of Gothenburg Abstract In Cooper‘s -

James Fenimore Cooper, Author (PDF)

James Fenimore Cooper Agenda Biography………………….Alexis Malaszuk Historical Context…………Kelly Logan Influences………………….Brian Carroccio Physical Description of Van Wyck House...…Joanna Maehr & Kirsten Strand MjMajor Literary Wor ks……... KiKrist in King Lesson Plan………………..Kelly Logan & Alexis Malaszuk Guidebook………………...Joanna Maehr & Kirsten Strand Web Site Design…………..Brian Carroccio & Kristin King James Fenimore Cooper Online Click here Thesis Statement James Fenimore Cooper was one of America’s first great novelists because he helped to create a sense of American history through his writinggps. Cooper was influenced g gyreatly by nature and wrote about it frequently in his novels. Cooper was also influenced by andblihHdRid wrote about places in the Hudson River Valley, such as the Van Wyck House. Biography James Fenimore Cooper (September 15, 1789-1789-SeptemberSeptember 14, 1851) Born in Burlllington, NJ, to a Married Susan DeLancey in wealthy, landowning judge 1811 and settled down as a ((p)William Cooper) gentleman farmer Attended Yale University at The couple moved abroad, age 13 but was expelled in his but he energetically defended third year AidAmerican democracy w hile Sent to sea as a merchant overseas marine Served three years in the US Navy as a midshipman Biography Cooper’s views were considered “conservative” and “aristocratic” – made him unpppopular as a social commentator His works were more pppopular overseas than in America His novels are said to “engage historical themes” Helppppyed to form the popular view of American history Cooper died in 1851, and is buried in the cemetery of Coopp,erstown, NY Historical Context James Fenimore Cooper grew up during the dawn of the 19 th CtCentury, wh en Amer icans were occu pipying, clearing, and farming more land than ever before. -

Century American Allegory

UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations 1-1-1999 The art of truth: The architecture of 19th -century American allegory Gary Brian Bennett University of Nevada, Las Vegas Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/rtds Repository Citation Bennett, Gary Brian, "The art of truth: The architecture of 19th -century American allegory" (1999). UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations. 3092. http://dx.doi.org/10.25669/4a8r-dftp This Dissertation is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Scholarship@UNLV with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Dissertation in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. This Dissertation has been accepted for inclusion in UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been raproducad from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy sulsmitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while othersbe frommay any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction Is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print t)leedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In ttie unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. -

THE PENNY PRESS Seeking Only Their Own Ends Was Threatening the Bonds of CHAPTER1 Community

THE AGE OF EGALITARIANISM: THE PENNY PRESS seeking only their own ends was threatening the bonds of CHAPTER 1 community. His growing disaffection led him to attack Amer- ican newspapers. He did so in an extended series of libel suits; in his characterization of a newspaper editor, the disgusting Steadfast Dodge who appeared in Homeward Bound (1838) THE REVOLUTION IN and Home As Found (1838); and in The American Democrat (1838), a short work of political criticism. In that work he AMERICAN JOURNALISM IN wrote: If newspapers are useful in overthrowing tyrants, it is only to THE AGE OF establish a tyranny of their own. The press tyrannizes over publick men, letters, the arts, the stage, and even over private life. Under the EGALITARIANISM: pretence of protecting publick morals, it is corrupting them to the core, and under the semblance of maintaining liberty, it is gradually establi;hing a despotism as ruthleu, as grasping, and one that is THE PENNY PRESS quite as vulgar as that of any christian state known. With loud professions of freedom of opinion, there is no tolerance; with a parade.of patriotism, no sacrifice of interests; and with fulsome panegyrics on propriety, too frequently, no decency.' Perhaps this is suggestive of the state of the American press BIRTH, education, and marriage, James Fenimore in the 1830s; more surely it represents a piotest of established BY Cooper was an American aristocrat. For him, power and power against a democratized-in this case, middle-class- prestige were always near at hand. But he was also an ardent social order.