James Fenimore Cooper: Entrepreneur of the Self

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Moral Geography of Cooper's Miles Wallingford Novels by Donald A

The Moral Geography of Cooper's Miles Wallingford Novels by Donald A. Ringe ecause he is so well known for his five Leatherstocking tales, James · Fenimore Cooper is most often associated with such New York settings as Otsego Lake, the scene of The Pioneers (1823) and The Demlayer (1841), or other partsB of the upstate wilderness, the setting for The Last of the Mohi cans (1826) and The Pathfinder (1840). But these are not the only parts of New York that Cooper uses in his novels. Equall y important is the lower Hudson Valley between Albany and New York City, an area he used in both The Spy (182 1) and in parts of Satanstoe (1845), but which plays an especiall y significant role in his double novel of 1844, Afloat and Ashore and Miles Wallingford. The ashore part of his book is set for the most part on Clawbonny, a farm in Ulster County. It is the home of five generations of Mi les Wallingfords, the first of whom "had purchased it of the Dutch colonist who had originall y cleared it from the woods."! T his is the point from which the latest Miles, the narrator of the novel, embarks on his four sea voyages and to which he returns at last when his many adventures are over. T hough the action of the novel takes place between 1797 and 1804, the narration occurs some forty years later as the sixty-year old Miles Wallingford recounts the adventures of his yo uth. T his 52 The Hudson Valley Regional Review, September 1985, Vo lume 2, Number 2 method of narrati on give Cooper a number of adval1lages. -

James Fenimore Cooper and the Genteel Hero of Romance

INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., was part of the material being photographed the photographer followed a definite method in "sectioning" the material. It is customary to begin photoing at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue photoing from left to right in equal sections with a small overlap. If necessary, sectioning is continued again — beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. The majority of users indicate that the textual content is of greatest value, however, a somewhat higher quality reproduction could be made from "photographs" if essential to the understanding of the dissertation. -

James Fenimore Cooper's Frontier: the Pioneers As History Thomas Berson

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2004 James Fenimore Cooper's Frontier: The Pioneers as History Thomas Berson Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES JAMES FENIMORE COOPER’S FRONTIER: THE PIONEERS AS HISTORY By THOMAS BERSON A Thesis Submitted to the Progra In A erican and Florida Studies in partial fulfill ent of the require ents for the degree of Master of Arts Degree Awarded: Sum er Se ester, 2004 The members of the Committee approve the thesis of Thomas Berson defended on July 1, 2004. --------------------------- Frederick Davis Professor Directing Thesis ---------------------------- John Fenstermaker Committee Member ---------------------------- Ned Stuckey-French Committee Member Approved: ------------------------------ John Fenstermaker, Chair, Program in American and Florida Studies ------------------------------ Donald Foss, Dean, College of Arts and Sciences The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii For My Parents iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Special thanks to John Fenstermaker, who gave me the opportunity to come back to school and to teach and to Fritz Davis, who helped me find direction in my studies. Additional thanks to the aforementioned and also to Ned Stuckey-French for taking the time out of their summers to sit on the committee for this paper. iv TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract................................................................................................................ -

Read Book the Leatherstocking Tales: the Library of America Edition

THE LEATHERSTOCKING TALES: THE LIBRARY OF AMERICA EDITION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK James Fenimore Cooper,Blake Nevius | 2126 pages | 19 Jan 2012 | Library of America | 9781598531541 | English | United States The Leatherstocking Tales: The Library of America Edition PDF Book Both these stories are fairly well-paced, with great characters, some action, and suspense. Niles Perkins rated it it was amazing Aug 05, Show More Show Less. James Fenimore Cooper. The weakest of the four I've thus far tackled, determination is the key to completing them. See review of Vol. Enacting a rite of passage both for its hero and for the culture he comes to represent, this last book in the series glows with a timelessness that readers everywhere will find enchanting. Refresh and try again. Books by James Fenimore Cooper. Collected here in a single Library of America volume, they are among his finest works. Forced into a life of piracy, the Rover conducts his private war of independence in a story that equates the free and daring life with the American dream of self-reliance and liberty from British rule. Sign me up to get more news about Historical Fiction books. The lowest-priced brand-new, unused, unopened, undamaged item in its original packaging where packaging is applicable. More filters. Goodreads helps you keep track of books you want to read. With his second novel, The Spy:A Tale of the Neutral Ground, in , James Cooper the Fenimore would come later found his true voice and what became his most enduring subject matter: the history of his young nation, born of the clash between Old World and New. -

The Link to James Fenimore Cooper?

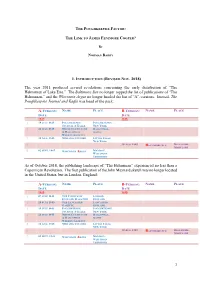

THE POUGHKEEPSIE FACTOR: THE LINK TO JAMES FENIMORE COOPER? BY NORMAN BARRY I. INTRODUCTION (REVISED NOV. 2018) The year 2011 produced several revelations concerning the early distribution of “The Helmsman of Lake Erie.” The Baltimore Sun no longer topped the list of publications of “The Helmsman,” and the Wisconsin Argus no longer headed the list of “A”-versions. Instead, The Poughkeepsie Journal and Eagle was head of the pack: A-VERSION: NAME PLACE B-VERSION: NAME PLACE DATE DATE 1845: 1845: 1 19 JULY 1845 POUGHKEEPSIE POUGHKEEPSIE, JOURNAL & EAGLE NEW YORK 2 26 JULY 1845 MAINE CULTIVATOR HALLOWELL, & HALLOWELL MAINE WEEKLY GAZETTE 3 14 AUG. 1845 MOHAWK COURIER LITTLE FALLS, NEW YORK 4 30 AUG. 1845 BALTIMORE SUN BALTIMORE, MARYLAND 02 SEPT. 1845 MADISON, 5 WISCONSIN ARGUS WISCONSIN TERRITORY As of October 2018, the publishing landscape of “The Helmsman” experienced no less than a Copernican Revolution. The first publication of the John Maynard sketch was no longer located in the United States, but in London, England: A-VERSION: NAME PLACE B-VERSION: NAME PLACE DATE DATE 1845: 1845: 1 07 JUNE 1845 THE CHURCH OF LONDON, ENGLAND MAGAZINE ENGLAND 2 14 JUNE 1845 THE LANCASTER LANCASTER, GAZETTE ENGLAND 3 19 JULY 1845 POUGHKEEPSIE POUGHKEEPSIE, JOURNAL & EAGLE NEW YORK 4 26 JULY 1845 MAINE CULTIVATOR HALLOWELL, & HALLOWELL MAINE WEEKLY GAZETTE 5 14 AUG. 1845 MOHAWK COURIER LITTLE FALLS, NEW YORK 6 30 AUG. 1845 BALTIMORE SUN BALTIMORE, MARYLAND 02 SEPT. 1845 MADISON, 7 WISCONSIN ARGUS WISCONSIN TERRITORY 1 The discovery of The Church of England Magazine as the very first publication of “The Helmsman of Lake Erie” in no way diminishes the importance of Poughkeepsie as the first place of publication in the United States. -

James Fenimore Cooper: Young Man to Author

Syracuse University SURFACE The Courier Libraries Spring 1988 James Fenimore Cooper: Young Man to Author Constantine Evans Syracuse University Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/libassoc Part of the American Literature Commons, and the Military History Commons Recommended Citation Evans, Constantine. "James Fenimore Cooper: Young Man to Author." The Courier 23.1 (1988): 57-77. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Libraries at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Courier by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SYRACUSE UNIVERSITY LIBRARY ASSOCIATES COURIER VOLUME XXIII, NUMBER 1, SPRING 1988 SYRACUSE UNIVERSITY LIBRARY ASSOCIATES COURIER VOLUME XXIII NUMBER ONE SPRING 1988 The Forgotten Brother: Francis William Newman, Victorian Modernist By Kathleen Manwaring, Syracuse University Library 3 The Joseph Conrad Collection at Syracuse University By J. H. Stape, Visiting Associate Professor of English, 27 Universite de Limoges The Jean Cocteau Collection: How 'Astonishing'? By Paul J. Archambault, Professor of French, 33 Syracuse University A Book from the Library of Christoph Scheurl (1481-1542) By Gail P. Hueting, Librarian, University of Illinois at 49 Urbana~Champaign James Fenimore Cooper: Young Man to Author By Constantine Evans, Instructor in English, 57 Syracuse University News of the Syracuse University Library and the Library Associates 79 James Fenimore Cooper: Young Man to Author BY CONSTANTINE EVANS The distinctive event that marks the beginning of Cooper's prog~ ress towards a career as an author took place in 1805, when at age sixteen he left Yale College in disgrace. -

IN Ronald J. Ambrosetti a Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate School

A STUDY OP THE SPY GENRE IN RECENT POPULAR LITERATURE Ronald J. Ambrosetti A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate School of Bowling Green State University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OP PHILOSOPHY August 1973 11 ABSTRACT The literature of espionage has roots which can be traced as far back as tales in the Old Test ament. However, the secret agent and the spy genre remained waiting in the wings of the popular stage until well into the twentieth century before finally attracting a wide audience. This dissertation analyzed the spy genre as it reflected the era of the Cold War. The Damoclean Sword of the mid-twentieth century was truly the bleak vision of a world devastated by nuclear pro liferation. Both Western and Communist "blocs" strove lustily in the pursuit of the ultimate push-button weapons. What passed as a balance of power, which allegedly forged a détente in the hostilities, was in effect a reign of a balance of terror. For every technological advance on one side, the other side countered. And into this complex arena of transis tors and rocket fuels strode the secret agent. Just as the detective was able to calculate the design of a clock-work universe, the spy, armed with the modern gadgetry of espionage and clothed in the accoutrements of the organization man as hero, challenged a world of conflicting organizations, ideologies and technologies. On a microcosmic scale of literary criticism, this study traced the spy genre’s accurate reflection of the macrocosmic pattern of Northrop Frye’s continuum of fictional modes: the initial force of verisimili tude was generated by Eric Ambler’s early realism; the movement toward myth in the technological romance of Ian Fleming; the tragic high-mimesis of John Le Carre' and the subsequent devolution to low-mimesis in the spoof; and the final return to myth in religious affir mation and symbolism. -

James Fenimore Cooper, Author (PDF)

James Fenimore Cooper Agenda Biography………………….Alexis Malaszuk Historical Context…………Kelly Logan Influences………………….Brian Carroccio Physical Description of Van Wyck House...…Joanna Maehr & Kirsten Strand MjMajor Literary Wor ks……... KiKrist in King Lesson Plan………………..Kelly Logan & Alexis Malaszuk Guidebook………………...Joanna Maehr & Kirsten Strand Web Site Design…………..Brian Carroccio & Kristin King James Fenimore Cooper Online Click here Thesis Statement James Fenimore Cooper was one of America’s first great novelists because he helped to create a sense of American history through his writinggps. Cooper was influenced g gyreatly by nature and wrote about it frequently in his novels. Cooper was also influenced by andblihHdRid wrote about places in the Hudson River Valley, such as the Van Wyck House. Biography James Fenimore Cooper (September 15, 1789-1789-SeptemberSeptember 14, 1851) Born in Burlllington, NJ, to a Married Susan DeLancey in wealthy, landowning judge 1811 and settled down as a ((p)William Cooper) gentleman farmer Attended Yale University at The couple moved abroad, age 13 but was expelled in his but he energetically defended third year AidAmerican democracy w hile Sent to sea as a merchant overseas marine Served three years in the US Navy as a midshipman Biography Cooper’s views were considered “conservative” and “aristocratic” – made him unpppopular as a social commentator His works were more pppopular overseas than in America His novels are said to “engage historical themes” Helppppyed to form the popular view of American history Cooper died in 1851, and is buried in the cemetery of Coopp,erstown, NY Historical Context James Fenimore Cooper grew up during the dawn of the 19 th CtCentury, wh en Amer icans were occu pipying, clearing, and farming more land than ever before. -

Curriculum Vitae

James P. Elliott CURRICULUM VITAE Department of English Clark University 950 Main Street Worcester, MA 01610 (508) 793-7152 e-mail: [email protected] EDUCATION: 1966-71 Indiana University Ph.D. in English Dissertation: “A Critical Edition of W. D. Howells’ The Quality of Mercy” 1962-66 Stanford University B.A. in English EMPLOYMENT: English Department, Clark University 2009- Chair 2004- Professor of English 1977-2004 Associate Professor of English 1979-80 Adjunct Professor of Film Studies 1971-77 Assistant Professor of English Worcester Polytechnic Institute 1981-82 Consultant and Adjunct Professor in Literature and Film Indiana University 1969-71 Research Assistant, A Selected Edition of William Dean Howells SCHOLARLY APPOINTMENTS: 1971- Member, Editorial Board, The Edition of the Writings of James Fenimore Cooper, co-sponsored by Clark University and the American Antiquarian Society 1979- Chief Textual Editor, Cooper Edition 1971-78 Textual Editor, Cooper Edition PUBLICATIONS EDITIONS PRIMARY EDITORIAL RESPONSIBILITY Cooper, James Fenimore. The Spy. Historical Introduction by James P. Elliott. Explanatory Notes by James Pickering. Text Established by James P. Elliott, Lance Schachterle, and Jeffrey Walker. NY: AMS Press, 2002. Rpt. With Lionel Lincoln and The Pilot. NY: Library of America, 2002. Cooper, James Fenimore. The Prairie. Edited, with Introduction and Explanatory Notes, by James P. Elliott. Albany, NY: SUNY Press, 1983. Rpt. with The Pioneers and The Last of the Mohicans. NY: Library of America, 1994. Rpt. Viking-Penguin, 1985. Rpt. Oxford UP, 1996 Howells, W.D. The Quality of Mercy. Introduction and Notes to the Text by James James P. Elliott Curriculum Vitae Page 2 of 4 P. -

Cooper, James Feminore, Papers, 1792

American Antiquarian Society Manuscript Collections NAME OF COLLECTION : LOCATION : Cooper, James Fenimore, Papers, 1792-1884 Mss. boxes "C" Oversize mss. boxes "C" SIZE OF COLLECTION : 7 manuscript boxes; 1 oversize manuscript box SOURCES OF INFORMATION ON COLLECTION : The Letters and Journals of James Fenimore Cooper , ed. by James Franklin Beard. 6 vols. (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1960-1968). Robert E. Spiller and Philip C. Blackburn. A Descriptive Bibliography of the Writings of James Fenimore Cooper . (New York: Bowker, 1934) SOURCE OF COLLECTION : One letter, dated 25? February 1832 to Armand Carrel, was purchased from George S. MacManus Co., 1983. Two letters, dated 22 May 1826 and 7 July 1827, was purchased from Ximenes Books, 1986. One letter , bound into The Deerslayer , was purchased from Argonaut Books, 1987. The remainder of the collection was the gift of the Paul Fenimore Cooper, Jr. estate, 1990. COLLECTION DESCRIPTION : James Fenimore Cooper (1789-1851), the son of William Cooper (1754-1809) and Elizabeth Fenimore Cooper (1752-1817), was born in Burlington, N.J., but spent his youth at Otsego Hall in Cooperstown, N.Y., the home of his father. After an early education at the public school in Cooperstown and at the home of an Episcopal rector in Albany, he attended Yale University for three years. In 1806 he went to sea, receiving a commission as a navy midshipman in 1808. His marriage to Susan Augusta De Lancy (1792-1852) of Westchester County, N.Y., took place in 1811, when he also resigned from the navy. In the years immediately following their marriage, the Coopers lived in Mamaroneck, Cooperstown, Scarsdale (where he began writing), and New York, N.Y. -

James Fenimore Cooper As a War Novelist

James Fenimore Cooper as a War Novelist Jozef Pecina University of Ss. Cyril and Methodius, Trnava, Slovakia Abstract James Fenimore Cooper was the first internationally recognized American novelist and a pioneer in the field of frontier and sea novels. His Leatherstocking Tales are among his most famous works, but he is also the author of a number of novels set during the American Revolution. The Spy: A Tale of the Neutral Ground (1821) and Lionel Lincoln; or, The Leaguer of Boston (1825) are early examples of what may be termed military novels. In both Cooper relied on extensive research and in both he used important events of the Revolution as a background for the actions of his characters. The article examines Cooper’s treatment of war and the role that his novels played in the development of the war novel genre. Keywords historical novel; American Revolution; war in fiction; battlefield realism; James Fenimore Cooper The beginnings of American writing about war date back to the 1820s, when the first novels dealing with the War of Independence appeared. The Revolution was used as a setting for a handful of gothic or sentimental novels, but until the publication of James Fenimore Cooper’s The Spy: A Tale of the Neutral Ground (1821), no work appeared that could be described as a war novel. Later in the decade, Cooper wrote another novel that is set during the Revolution, Lionel Lincoln; or, The Leaguer of Boston (1825); it is these two novels that I will analyze in this article. Literary critics deem both works to be historical novels. -

James Fenimore Cooper and the Invention of the Passing Novel

Geoffrey James Fenimore Cooper and the Sanborn Invention of the Passing Novel The trouble with racism, for James Fenimore Cooper, is that it is too subtle. “We will not enter upon any subtle deductions which involve national character, or national enterprise and aptitude for sea- service,” he writes in an 1821 essay. “We leave such nice dis- tinctions for greater ingenuity than we can pretend to.”1 In opposition to “theorists” who insist on “the inferiority of all . who [are] not white,” he declares that there is no such thing as “general national superiority.”2 In opposition to metaphysicians who “reason as subtly as they can about the races and colors,” he argues that the “moral tone” of one’s behavior “depend[s] more on the conventional feel- ing . got up through moral agencies, than on birth-place, origin, or colour.”3 In the case of whites and Indians in the trans- Mississippi West, he writes in The Prairie (1827), it would take a “curious investi- gation” to identify the “points of difference” by which they were “still to be distinguished . now that the two, in the revolutions of the world, were approximating in their habits, their residence and not a little in their characters.”4 But racism is, Cooper recognizes, subtle in another way as well. Thanks to the power of “self- love,” an “unquiet spirit which haunts us to the last,” no one is immune to “the vulgar prejudice of national superiority . one of the strongest of all the weaknesses of our very weak nature.”5 “It is possible,” writes Corny Littlepage in The Chain- bearer (1845),