Durham E-Theses

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Festival Fever Sequel Season Fashion Heats Up

arts and entertainment weekly entertainment and arts THE SUMMER SEASON IS FOR MOVIES, MUSIC, FASHION AND LIFE ON THE BEACH sequelmovie multiples season mean more hits festival fever the endless summer and even more music fashionthe hemlines heats rise with up the temps daily.titan 2 BUZZ 05.14.07 TELEVISION VISIONS pg.3 One cancelled in record time and another with a bleak future, Buzz reviewrs take a look at TV show’s future and short lived past. ENTERTAINMENT EDITOR SUMMER MOVIE PREVIEW pg.4 Jickie Torres With sequels in the wings, this summer’s movie line-up is a EXECUTIVE EDITOR force to be reckoned with. Adam Levy DIRECTOR OF ADVERTISING Emily Alford SUIT SEASON pg.6 Bathing suit season is upon us. Review runway trends and ASSISTANT DIRECTOR OF ADVERTISING how you can rock the baordwalk on summer break. Beth Stirnaman PRODUCTION Jickie Torres FESTIVAL FEVER pg.6 ACCOUNT EXECUTIVES Summer music festivals are popping up like the summer Sarah Oak, Ailin Buigis temps. Take a look at what’s on the horizon during the The Daily Titan 714.278.3373 summer months. The Buzz Editorial 714.278.5426 [email protected] Editorial Fax 714.278.4473 The Buzz Advertising 714.278.3373 [email protected] Advertising Fax 714.278.2702 The Buzz , a student publication, is a supplemental insert for the Cal State Fullerton Daily Titan. It is printed every Thursday. The Daily Titan operates independently of Associated Students, College of Communications, CSUF administration and the WHAT’S THE BUZZ p.7 CSU system. The Daily Titan has functioned as a public forum since inception. -

Mark Summers Sunblock Sunburst Sundance

Key - $ = US Number One (1959-date), ✮ UK Million Seller, ➜ Still in Top 75 at this time. A line in red Total Hits : 1 Total Weeks : 11 indicates a Number 1, a line in blue indicate a Top 10 hit. SUNFREAKZ Belgian male producer (Tim Janssens) MARK SUMMERS 28 Jul 07 Counting Down The Days (Sunfreakz featuring Andrea Britton) 37 3 British male producer and record label executive. Formerly half of JT Playaz, he also had a hit a Souvlaki and recorded under numerous other pseudonyms Total Hits : 1 Total Weeks : 3 26 Jan 91 Summers Magic 27 6 SUNKIDS FEATURING CHANCE 15 Feb 97 Inferno (Souvlaki) 24 3 13 Nov 99 Rescue Me 50 2 08 Aug 98 My Time (Souvlaki) 63 1 Total Hits : 1 Total Weeks : 2 Total Hits : 3 Total Weeks : 10 SUNNY SUNBLOCK 30 Mar 74 Doctor's Orders 7 10 21 Jan 06 I'll Be Ready 4 11 Total Hits : 1 Total Weeks : 10 20 May 06 The First Time (Sunblock featuring Robin Beck) 9 9 28 Apr 07 Baby Baby (Sunblock featuring Sandy) 16 6 SUNSCREEM Total Hits : 3 Total Weeks : 26 29 Feb 92 Pressure 60 2 18 Jul 92 Love U More 23 6 SUNBURST See Matt Darey 17 Oct 92 Perfect Motion 18 5 09 Jan 93 Broken English 13 5 SUNDANCE 27 Mar 93 Pressure US 19 5 08 Nov 97 Sundance 33 2 A remake of "Pressure" 10 Jan 98 Welcome To The Future (Shimmon & Woolfson) 69 1 02 Sep 95 When 47 2 03 Oct 98 Sundance '98 37 2 18 Nov 95 Exodus 40 2 27 Feb 99 The Living Dream 56 1 20 Jan 96 White Skies 25 3 05 Feb 00 Won't Let This Feeling Go 40 2 23 Mar 96 Secrets 36 2 Total Hits : 5 Total Weeks : 8 06 Sep 97 Catch Me (I'm Falling) 55 1 20 Oct 01 Pleaase Save Me (Sunscreem -

Conceptualizing Success: Aspirations of Four Young Black

CONCEPTUALIZING SUCCESS: ASPIRATIONS OF FOUR YOUNG BLACK GUYANESE IMMIGRANT WOMEN FOR HIGHER EDUCATION by ALICIA KELLY A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Education in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Master of Education Queen’s University Kingston, Ontario, Canada April, 2009 Copyright © Alicia Kelly, 2009 ABSTRACT During the past four decades researchers note that educational institutions fail to “connect” with minority students (e.g. Clark, 1983; Coelho, 1998; Dei, 1994; Duffy, 2003; Ogbu, 1978, 1991). Carr and Klassen (1996) define this lack of “connection” primarily as teachers’ disregard for each student’s culture as it relates to race, and thus, his or her achievement potential. Hence, this disregard encourages minority students to question their ability to be successful. Dei (1994), furthermore, shows a tremendous disconnectedness from schools and education systems being felt by Black students. Few studies give voice to specific groups of Black female high school graduates who opt out of pursuing higher education. I interviewed four Black Guyanese immigrant women to: (a) investigate their reasons and expectations when immigrating to Canada, (b) identify what influenced their decision not to pursue postsecondary education, (c) explore their definitions of success, and (d) investigate how/if their notions of success relate to obtaining postsecondary education in Canada. Critical Race Theory (CRT) was employed in this study to: (a) provide a better understanding of the participants’ classroom dynamics governed by relationships with their teachers, guidance counsellors and school administrators, (b) examine educational outcomes governed by personal and educational relationships and experiences, and (c) provide conceptual tools in the investigation of colour-blindness (Parker & Roberts, 2005) that is disguised in Canadian education, immigration, and other government i policies. -

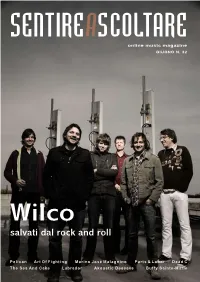

Salvati Dal Rock and Roll

SENTIREASCOLTARE online music magazine GIUGNO N. 32 Wilco salvati dal rock and roll Hans Appelqvist King Kong Laura Veirs Valet Keren Ann Feist Low PelicanStars Of The Art Lid Of Fighting Smog I Nipoti Marino del CapitanoJosé Malagnino Cristina Zavalloni Parts & Labor Billy Nicholls Dead C The Sea And Cake Labrador Akoustic Desease Buffys eSainte-Marie n t i r e a s c o l t a r e WWW.AUDIOGLOBE.IT VENDITA PER CORRISPONDENZA TEL. 055-3280121, FAX 055 3280122, [email protected] DISTRIBUZIONE DISCOGRAFICA TEL. 055-328011, FAX 055 3280122, [email protected] MATTHEW DEAR JENNIFER GENTLE STATELESS “Asa Breed” “The Midnight Room” “Stateless” CD Ghostly Intl CD Sub Pop CD !K7 Nuovo lavoro per A 2 anni di distan- Matthew Dear, uno za dal successo di degli artisti/produt- critica di “Valende”, È pronto l’omonimo tori fra i più stimati la creatura Jennifer debutto degli Sta- del giro elettronico Gentle, ormai nelle teless, formazione minimale e spe- sole mani di Mar- proveniente da Lee- rimentale. Con il co Fasolo, arriva al ds. Guidata dalla nuovo lavoro, “Asa Breed”, l’uomo di Detroit, si nuovo “The Midnight Room”, sempre su Sub voce del cantante Chris James, voluto anche rivela più accessibile che mai. Sì certo, rima- Pop. Registrato presso una vecchia e sperduta da DJ Shadow affinché partecipasse alle regi- ne il tocco à la Matthew Dear, ma l’astrattismo casa del Polesine ed ispirato forse da questa strazioni del suo disco, la formazione inglese usuale delle sue produzioni pare abbia lasciato sinistra collocazione, il nuovo album si districa mette insieme guitar sound ed elettronica, ri- uno spiraglio a parti più concrete e groovy. -

Viral Spiral Also by David Bollier

VIRAL SPIRAL ALSO BY DAVID BOLLIER Brand Name Bullies Silent Theft Aiming Higher Sophisticated Sabotage (with co-authors Thomas O. McGarity and Sidney Shapiro) The Great Hartford Circus Fire (with co-author Henry S. Cohn) Freedom from Harm (with co-author Joan Claybrook) VIRAL SPIRAL How the Commoners Built a Digital Republic of Their Own David Bollier To Norman Lear, dear friend and intrepid explorer of the frontiers of democratic practice © 2008 by David Bollier All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, in any form, without written permission from the publisher. The author has made an online version of the book available under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial license. It can be accessed at http://www.viralspiral.cc and http://www.onthecommons.org. Requests for permission to reproduce selections from this book should be mailed to: Permissions Department, The New Press, 38 Greene Street, New York,NY 10013. Published in the United States by The New Press, New York,2008 Distributed by W.W.Norton & Company,Inc., New York ISBN 978-1-59558-396-3 (hc.) CIP data available The New Press was established in 1990 as a not-for-profit alternative to the large, commercial publishing houses currently dominating the book publishing industry. The New Press operates in the public interest rather than for private gain, and is committed to publishing, in innovative ways, works of educational, cultural, and community value that are often deemed insufficiently profitable. www.thenewpress.com A Caravan book. For more information, visit www.caravanbooks.org. Composition by dix! This book was set in Bembo Printed in the United States of America 10987654321 CONTENTS Acknowledgments vii Introduction 1 Part I: Harbingers of the Sharing Economy 21 1. -

Colocation Aware Content Sharing in Urban Transport

Colocation Aware Content Sharing in Urban Transport Liam James John McNamara A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of the University College London. Department of Computer Science January 2010 I, Liam James John McNamara confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. i Abstract People living in urban areas spend a considerable amount of time on public transport. During these periods, opportunities for inter-personal networking present themselves, as many of us now carry electronic devices equipped with Bluetooth or other wireless capabilities. Using these devices, individuals can share content (e.g., music, news or video clips) with fellow travellers that happen to be on the same train or bus. Transferring media takes time; in order to maximise the chances of successfully completing interesting downloads, users should identify neighbours that possess desirable content and who will travel with them for long-enough periods. In this thesis, a peer-to-peer content distribution system for wireless devices is proposed, grounded on three main contributions: (1) a technique to predict colocation durations (2) a mechanism to exclude poorly performing peers and (3) a library advertisement protocol. The prediction scheme works on the observation that people have a high degree of regularity in their movements. Ensuring that content is accurately described and delivered is a challenge in open networks, requiring the use of a trust framework, to avoid devices that do not behave appro- priately. -

History Report Freiburg HOT 24.02.2016 00 Through 01.03.2016 23

History Report Freiburg_HOT 24.02.2016 00 through 01.03.2016 23 Air Date Air Time Cat RunTime Artist Keyword Title Keyword Mi 24.02.2016 00:05 ARO 02:37 Basia Bulat Fool Mi 24.02.2016 00:08 ARO 03:55 Liima Amerika Mi 24.02.2016 00:12 DPR 03:52 Tocotronic Let there be rock Mi 24.02.2016 00:15 HIP 04:50 Black Twang So Rotton feat. Jahmali Mi 24.02.2016 00:20 SRO 02:19 Reverend And The Makers Mr Glasshalfempty Mi 24.02.2016 00:23 RCK 03:04 Oasis Hello Mi 24.02.2016 00:26 DPR 02:41 Tom Liwa & Flowerpornoes Planetenkind Mi 24.02.2016 00:28 NAC 03:25 Belle And Sebastian Get me away from here I'm dyin Mi 24.02.2016 00:32 ARO 03:55 Alligatoah Teamgeist Mi 24.02.2016 00:36 POP 03:23 Mumm-Ra She's got you high Mi 24.02.2016 00:39 SRO 04:05 Stereo Total Zu schön für dich Mi 24.02.2016 00:43 NAC 05:02 Richard Ashcroft C'mon People (We're Making It Now) Mi 24.02.2016 00:48 NAC 03:26 Shooting John Thirteen Highway Blues Mi 24.02.2016 00:52 EKR 03:54 Powernerd BMX Mi 24.02.2016 00:55 ARO 04:52 Yeasayer I Am Chemistry Mi 24.02.2016 00:60 EKR 03:07 Caribou Found Out Mi 24.02.2016 00:63 POP 03:37 Athlete Half Light Mi 24.02.2016 00:67 NAC 03:35 Teitur Shade Of A Shadow Mi 24.02.2016 00:71 NAC 06:02 Phosphorescent Cocaine Lights Mi 24.02.2016 01:05 NAC 03:31 Pelle Carlberg Telemarketing Mi 24.02.2016 01:09 J 00:02 Flüsterer_Ids2 Mi 24.02.2016 01:09 RCK 02:02 The Octagon Vermeer Mi 24.02.2016 01:11 SRO 04:18 DOTA Grenzen Mi 24.02.2016 01:15 POP 03:25 Hurricane #1 Think Of The Sunshine Mi 24.02.2016 01:18 NAC 02:21 Lea Rohm Maybe You Are (Asaf Avidan Cover) -

Oriol Tramvia El Punk Abans De Sex Pistols & Astrud + Hidrogenesse Guia De Looks I Cd Sònar Festivals D’Estiu 2007

e JULIO enderrock 140 MANRIQUE EMPAR MOLINER SAÜL GORDILLO LA TRINCA PARLEN ELS HEREUS ORIOL TRAMVIA EL PUNK ABANS DE SEX PISTOLS & ASTRUD + HIDROGENESSE GUIA DE LOOKS I CD SÒNAR FESTIVALS D’ESTIU 2007 NÚM. 140 SENGLAR ROCK LLEIDA JUNY 2007 ANY XIII ACAMPADA JOVE / POPARB EDR + CD: 4,95 ¤ ANÒLIA / CULTURAVIVA + PÒSTER DESPLEGABLE LAX’N’BUSTO ≠ SUMARI / 05 ********************************************************************************************************** 140 06 El retrat Miquel Mariano 08 Editorial 10 Cracks EDR Empar Moliner 12 Cracks EDR Julio Manrique 14 Cracks EDR Saül Gordillo 16 Sospitosos habituals [PER ALBERT PUIG] 32 40 Estanislau Verdet 18 20 22 24 Breus Joan Miquel Oliver / Aramateix i Mesclat/ Xerramequ Tiquis Miquis / La Carrau / Muchachito Bombo Infierno / Pi de la Serra / May Xartó / Sisa / HOT DISCOS / Guillamino + Pedrals / Anonymous / Mar Abella / Marfan / Nito Figueras / Buhos / Txipi Aité / Ariabàscia / A RAIG: Anna Cerdà (PopArb) 26 MALL Martell de Ponent ANITA MILTOFF Mestres de l’odi i de l’amor 28 XAVI LLOSES El camí cap a l’estratosfera 29 NACHO CHAPADO DJ Remixcòbol 30 KUMBES DEL MAMBO Festa i ‘catxondeio’ 55 46 BORDER LINE BLUES BAND Blues de l’Onyar 31 DUBLE BUBLE La segona joventut 58 Discos cat / Discos int 62 Sona 9 Vitruvi / Maquetes / Connecta ’07 / 32 ASTRUD & HIDROGENESSE Això és el que hi ha Ebre Musik / Concurs de Música de Badalona GUERRA 34 ANEGATS Pop-rock de fora vila 64 Concerts CAS ’07 / 300 anys de lluites i cançons / PER LA TERRA Gossos / Sanpedro / C.E. Dharma / Narcís Perich / 36 KABUL BABÀ La màfia del rock’n’roll Benvingut al paradís (Propaganda Fira de Música al Carrer de Vila-seca / La Gira 2007 pel Fet!, 2007) és un mostrari de 38 ORIOL TRAMVIA El primer punk europeu A final del 1976 les resistències del nou segle. -

Black Feminism in America

KU Leuven Faculty of Arts Blijde Inkomststraat 21 box 3301 3000 LEUVEN, BELGIË Black Feminism in America An Overview and Comparison of Black Feminism’s Destiny through Literature and Music up to Beyoncé Charlotte Theys Presented in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Literature and Linguistics Supervisor: prof. dr. Theo D’haen (promoter) Academic year 2014-2015. 160.632 characters Dankwoord Ik wil eerst en vooral mijn familieleden bedanken voor hun onvoorwaardelijke steun. Daarnaast ben ik ook Erik Van Damme zeer dankbaar die zijn interesse voor taal en literatuur aan mij heeft doorgegeven. Voor tips in verband met de lay-out wil ik dan weer Denise Jacobs bedanken. Voorts wil ik toch ook mijn dank betuigen aan professor Theo D’haen die mij de kans heeft gegeven om over dit onderwerp te schrijven. Tot slot, bedank ik nog al mijn vrienden en vriendinnen die mij emotioneel en mentaal hebben gesteund het afgelopen jaar. I Table of Contents Dankwoord ................................................................................................................................. I Table of Contents ..................................................................................................................... II Introduction .............................................................................................................................. 1 1. A Short History of American Suffragettes during First-Wave Feminism ................... 2 1.1. Colored Females on Their Pathway to Liberty ...................................................... -

Variations on a Theme: Forty Years of Music, Memories, and Mistakes

University of New Orleans ScholarWorks@UNO University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations Dissertations and Theses 5-15-2009 Variations on a Theme: Forty years of music, memories, and mistakes Christopher John Stephens University of New Orleans Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td Recommended Citation Stephens, Christopher John, "Variations on a Theme: Forty years of music, memories, and mistakes" (2009). University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations. 934. https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td/934 This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by ScholarWorks@UNO with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights- holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Variations on a Theme: Forty years of music, memories, and mistakes A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the University of New Orleans in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts In Creative Non-Fiction By Christopher John Stephens B.A., Salem State College, 1988 M.A., Salem State College, 1993 May 2009 DEDICATION For my parents, Jay A. Stephens (July 6, 1928-June 20, 1997) Ruth C. -

Media Monsters: Militarism, Violence, and Cruelty in Children’S Culture

MEDIA MONSTERS: MILITARISM, VIOLENCE, AND CRUELTY IN CHILDREN’S CULTURE By Heidi Tilney Kramer © Heidi Tilney Kramer, 2015. All rights reserved. This work is protected by Copyright and permission must be obtained from the author prior to reproducing any part of the text in print, electronic, or recording format. Thank you for being respectful and please know that permission will be granted in all likelihood due to the imperative nature of sharing this content. ISBN: 978-0-9742736-8-6 For Alex and the children everywhere: May we leave your world in a better state than when we arrived. Table of Contents Preface ......................................................................................... i Acknowledgments ...................................................................... v Introduction ................................................................................ 1 Chapter I: History of U.S. Media ............................................... 7 Chapter II: Music ...................................................................... 87 Chapter III: Education ............................................................ 125 Chapter IV: Television ........................................................... 167 Chapter V: General Influences on Kids .................................. 217 Chapter VI: Web-Based and Other Media ............................. 253 Chapter VII: Video Games ..................................................... 271 Chapter VIII: Film Industry/Movies ...................................... 295 Chapter -

--- Volume 60, Number 33 T Has Been Said That There Is More Than

, .. --- Volume 60, Number 33 assmusieeemiervimass...S.20V,..12Willk.. ,'Mal1.10.‘111111.111.1.111.111111111111111 T has been said that there is more suit that the God as described by the than one Deity revealed in the Bible. and loving Father, they say, came later early authors of the Old Testament as man progressed and became more Modernists and higher critics in differs from the latter conceptions of the -their reading of the Old Testament de- civilized, more tolerant himself, and not Almighty. so narrow and bigoted in his beliefs. scribe several gods, and blasphemously In support of this theory is cited the state that instead of God making man This conception of God, they say, was supposition that man's first conception finally transformed into the "God of in His own • image the reverse is true, of God was very primitive, and that God that man has made God in man's own love" belief manifested by New Testa- as described by early writers is a venge- ment writers. Dm a g e . By this they infer that as man ful, jealous God, requiring an eye for That several Deities, each one differ- ?assed through successive stages in his ah eye, and a tooth for a tooth, and inward, upward, evolutionary career, so ordering the wholesale destruction of ing in character outlook, and action are his conception of a Supreme Being revealed by a critical reading of the Old nations because they departed from Him. Testament, I will leave to theologians changed with these stages, with the re- The idea of a tolerant, all-wise, merciful, (Please turn to page 11) ((Registered at the G.P.O., Melbourne, for transmission by post as a newspaper.>> "The World's Last Chance" STATESMEN of today know the bit- ter rivalries and animosities that Current-Topics Neuitturdp' separate the nations of the world.