Black Feminism in America

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Songs by Artist

Sunfly (All) Songs by Artist Karaoke Shack Song Books Title DiscID Title DiscID (Comic Relief) Vanessa Jenkins & Bryn West & Sir Tom Jones & 3OH!3 Robin Gibb Don't Trust Me SFKK033-10 (Barry) Islands In The Stream SF278-16 3OH!3 & Katy Perry £1 Fish Man Starstrukk SF286-11 One Pound Fish SF12476 Starstrukk SFKK038-10 10cc 3OH!3 & Kesha Dreadlock Holiday SF023-12 My First Kiss SFKK046-03 Dreadlock Holiday SFHT004-12 3SL I'm Mandy SF079-03 Take It Easy SF191-09 I'm Not In Love SF001-09 3T I'm Not In Love SFD701-6-05 Anything FLY032-07 Rubber Bullets SF071-01 Anything SF049-02 Things We Do For Love, The SFMW832-11 3T & Michael Jackson Wall Street Shuffle SFMW814-01 Why SF080-11 1910 Fruitgum Company 3T (Wvocal) Simon Says SF028-10 Anything FLY032-15 Simon Says SFG047-10 4 Non Blondes 1927 What's Up SF005-08 Compulsory Hero SFDU03-03 What's Up SFD901-3-14 Compulsory Hero SFHH02-05-10 What's Up SFHH02-09-15 If I Could SFDU09-11 What's Up SFHT006-04 That's When I Think Of You SFID009-04 411, The 1975, The Dumb SF221-12 Chocolate SF326-13 On My Knees SF219-04 City, The SF329-16 Teardrops SF225-06 Love Me SF358-13 5 Seconds Of Summer Robbers SF341-12 Amnesia SF342-12 Somebody Else SF367-13 Don't Stop SF340-17 Sound, The SF361-08 Girls Talk Boys SF366-16 TOOTIMETOOTIMETOOTIME SF390-09 Good Girls SF345-07 UGH SF360-09 She Looks So Perfect SF338-05 2 Eivissa She's Kinda Hot SF355-04 Oh La La La SF114-10 Youngblood SF388-08 2 Unlimited 50 Cent No Limit FLY027-05 Candy Shop SF230-10 No Limit SF006-05 Candy Shop SFKK002-09 No Limit SFD901-3-11 In Da -

Songs by Artist

Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title &, Caitlin Will 12 Gauge Address In The Stars Dunkie Butt 10 Cc 12 Stones Donna We Are One Dreadlock Holiday 19 Somethin' Im Mandy Fly Me Mark Wills I'm Not In Love 1910 Fruitgum Co Rubber Bullets 1, 2, 3 Redlight Things We Do For Love Simon Says Wall Street Shuffle 1910 Fruitgum Co. 10 Years 1,2,3 Redlight Through The Iris Simon Says Wasteland 1975 10, 000 Maniacs Chocolate These Are The Days City 10,000 Maniacs Love Me Because Of The Night Sex... Because The Night Sex.... More Than This Sound These Are The Days The Sound Trouble Me UGH! 10,000 Maniacs Wvocal 1975, The Because The Night Chocolate 100 Proof Aged In Soul Sex Somebody's Been Sleeping The City 10Cc 1Barenaked Ladies Dreadlock Holiday Be My Yoko Ono I'm Not In Love Brian Wilson (2000 Version) We Do For Love Call And Answer 11) Enid OS Get In Line (Duet Version) 112 Get In Line (Solo Version) Come See Me It's All Been Done Cupid Jane Dance With Me Never Is Enough It's Over Now Old Apartment, The Only You One Week Peaches & Cream Shoe Box Peaches And Cream Straw Hat U Already Know What A Good Boy Song List Generator® Printed 11/21/2017 Page 1 of 486 Licensed to Greg Reil Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title 1Barenaked Ladies 20 Fingers When I Fall Short Dick Man 1Beatles, The 2AM Club Come Together Not Your Boyfriend Day Tripper 2Pac Good Day Sunshine California Love (Original Version) Help! 3 Degrees I Saw Her Standing There When Will I See You Again Love Me Do Woman In Love Nowhere Man 3 Dog Night P.S. -

Women, Gender, and Music During Wwii a Thesis

EDINBORO UNIVERSITY OF PENNSYLVANIA PITCHING PATRIARCHY: WOMEN, GENDER, AND MUSIC DURING WWII A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY, POLITICS, LANGUAGES, AND CULTURES FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS SOCIAL SCIENCES-HISTORY BY SARAH N. GAUDIOSO EDINBORO, PENNSYLVANIA APRIL 2018 1 Pitching Patriarchy: Women, Music, and Gender During WWII by Sarah N. Gaudioso Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Master of Social Sciences in History ApprovedJjy: Chairperson, Thesis Committed Edinbqro University of Pennsylvania Committee Member Date / H Ij4 I tg Committee Member Date Formatted with the 8th Edition of Kate Turabian, A Manual for Writers of Term Papers, Theses and Dissertations. i S C ! *2— 1 Copyright © 2018 by Sarah N. Gaudioso All rights reserved ! 1 !l Contents INTRODUCTION 1 CHAPTER 1: HISTORIOGRAPHY 5 CHAPTER 2: WOMEN IN MUSIC DURING WORLD WAR II 35 CHAPTER 3: AFRICAN AMERICAN WOMEN AND MUSIC DURING THE WAR.....84 CHAPTER 4: COMPOSERS 115 CHAPTER 5: CONCLUSIONS 123 BIBLIOGRAPHY 128 Gaudioso 1 INTRODUCTION A culture’s music reveals much about its values, and music in the World War II era was no different. It served to unite both military and civilian sectors in a time of total war. Annegret Fauser explains that music, “A medium both permeable and malleable was appropriated for numerous war related tasks.”1 When one realizes this principle, it becomes important to understand how music affected individual segments of American society. By examining women’s roles in the performance, dissemination, and consumption of music, this thesis attempts to position music as a tool in perpetuating the patriarchal gender relations in America during World War II. -

July 2018.Pub

Volume , Issue Tooele City Corporation July 2018 From the Mayor . I would like to 11 Year Old Scouts (JP Hansen) Sarah Garcia & Neighborhood personally thank ACE Disposal Families all of you who Aceneth Warner Scholar Academy 3rd Grade Classes parcipated in our Chartway Federal Credit Union St. Marguerite's Service #TakePrideTooele Eastridge LDS Young Women Tooele Boys and Girls Club Spring Clean Up (Emma Silos) Tooele County Associaon of project! I appreci- Emily Maughan & Neighbors Realtors ate those of you GFWC ‐ Ladies Group Tooele County Chamber of who took the me Girl Scout Troop 2330 Commerce and put in the Mayor (Melinda Firth) Tooele Girls Soball League hard work to Girl Scout Troop 2339 (Kris Vance) Debbie Winn clean up your (Kara Shuemaker) Tooele High Baseball Parents July Events yards, your neigh- James Gibbons & Joe McBride (Cameron Thevenot) *See Page 4 for 4th of July celebrations! borhoods and our community. Julie Smith and Family Tooele High Student Government July 2 Karaoke Contest, Corvette Car Show, I especially want to recognize Karen Williams (Cody Valdez, Advisor) and FREE Community BBQ at the Aquatic Center Park* those who parcipated in community LDS Whitaker Ward Tracy Shaw Family projects and volunteered their me to July 3 TERRI CLARK in concert at the THS Library Teen Advisory Council Keep up the great work! It takes all make this City great! Football Stadium 8:00 pm followed by Madeline Bracken & Family of us to keep Tooele City the beauful fireworks at approximately 10:00 pm* Maggie Mondragon — Spring Clean Middle Canyon Elementary 3rd place where we love to live, work, and play! July 3 Bit & Spur Rodeo at Deseret Peak Up Commiee Member Grade Classes (Jenine Gillie) Complex 8 pm* I want to wish you and your families Paul Simmons — Spring Clean Up Overlake 1st Ward Youth (Narda a happy and safe 4th and 24th of July July 4 Independence Day—City Offices will Commiee Member Emme) holidays! be closed. -

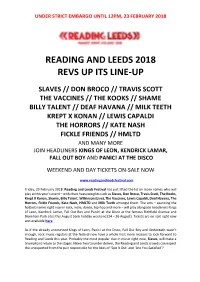

Reading and Leeds 2018 Revs up Its Line-Up

UNDER STRICT EMBARGO UNTIL 12PM, 23 FEBRUARY 2018 READING AND LEEDS 2018 REVS UP ITS LINE-UP SLAVES // DON BROCO // TRAVIS SCOTT THE VACCINES // THE KOOKS // SHAME BILLY TALENT // DEAF HAVANA // MILK TEETH KREPT X KONAN // LEWIS CAPALDI THE HORRORS // KATE NASH FICKLE FRIENDS // HMLTD AND MANY MORE JOIN HEADLINERS KINGS OF LEON, KENDRICK LAMAR, FALL OUT BOY AND PANIC! AT THE DISCO WEEKEND AND DAY TICKETS ON-SALE NOW www.readingandleedsfestival.com Friday, 23 February 2018: Reading and Leeds Festival has just lifted the lid on more names who will play at this year’s event – with chart heavyweights such as Slaves, Don Broco, Travis Scott, The Kooks, Krept X Konan, Shame, Billy Talent, Wilkinson (Live), The Vaccines, Lewis Capaldi, Deaf Havana, The Horrors, Fickle Friends, Kate Nash, HMLTD and Milk Teeth amongst them. The acts – spanning the hottest names right now in rock, indie, dance, hip-hop and more – will play alongside headliners Kings of Leon, Kendrick Lamar, Fall Out Boy and Panic! at the Disco at the famous Richfield Avenue and Bramham Park sites this August bank holiday weekend (24 – 26 August). Tickets are on-sale right now and available here. As if the already announced Kings of Leon, Panic! at the Disco, Fall Out Boy and Underøath wasn’t enough, rock music regulars at the festival now have a whole host more reasons to look forward to Reading and Leeds this year. Probably the most popular duo in music right now, Slaves, will make a triumphant return to the stages. Never two to under deliver, the Reading and Leeds crowds can expect the unexpected from the pair responsible for the likes of ‘Spit It Out’ and ‘Are You Satisfied’? UNDER STRICT EMBARGO UNTIL 12PM, 23 FEBRUARY 2018 With another top 10 album, ‘Technology’, under their belt, Don Broco will be joining the fray this year. -

(Pdf) Download

Artist Song 2 Unlimited Maximum Overdrive 2 Unlimited Twilight Zone 2Pac All Eyez On Me 3 Doors Down When I'm Gone 3 Doors Down Away From The Sun 3 Doors Down Let Me Go 3 Doors Down Behind Those Eyes 3 Doors Down Here By Me 3 Doors Down Live For Today 3 Doors Down Citizen Soldier 3 Doors Down Train 3 Doors Down Let Me Be Myself 3 Doors Down Here Without You 3 Doors Down Be Like That 3 Doors Down The Road I'm On 3 Doors Down It's Not My Time (I Won't Go) 3 Doors Down Featuring Bob Seger Landing In London 38 Special If I'd Been The One 4him The Basics Of Life 98 Degrees Because Of You 98 Degrees This Gift 98 Degrees I Do (Cherish You) 98 Degrees Feat. Stevie Wonder True To Your Heart A Flock Of Seagulls The More You Live The More You Love A Flock Of Seagulls Wishing (If I Had A Photograph Of You) A Flock Of Seagulls I Ran (So Far Away) A Great Big World Say Something A Great Big World ft Chritina Aguilara Say Something A Great Big World ftg. Christina Aguilera Say Something A Taste Of Honey Boogie Oogie Oogie A.R. Rahman And The Pussycat Dolls Jai Ho Aaliyah Age Ain't Nothing But A Number Aaliyah I Can Be Aaliyah I Refuse Aaliyah Never No More Aaliyah Read Between The Lines Aaliyah What If Aaron Carter Oh Aaron Aaron Carter Aaron's Party (Come And Get It) Aaron Carter How I Beat Shaq Aaron Lines Love Changes Everything Aaron Neville Don't Take Away My Heaven Aaron Neville Everybody Plays The Fool Aaron Tippin Her Aaron Watson Outta Style ABC All Of My Heart ABC Poison Arrow Ad Libs The Boy From New York City Afroman Because I Got High Air -

ELLINGTON '2000 - by Roger Boyes

TH THE INTERNATIONAL BULLETIN22 year of publication OEMSDUKE ELLINGTON MUSIC SOCIETY | FOUNDER: BENNY AASLAND HONORARY MEMBER: FATHER JOHN GARCIA GENSEL As a DEMS member you'll get access from time to time to / jj£*V:Y WL uni < jue Duke material. Please bear in mind that such _ 2000_ 2 material is to be \ handled with care and common sense.lt " AUQUSl ^^ jj# nust: under no circumstances be used for commercial JUriG w «• ; j y i j p u r p o s e s . As a DEMS member please help see to that this Editor : Sjef Hoefsmit ; simple rule is we \&! : T NSSESgf followed. Thus will be able to continue Assisted by: Roger Boyes ^ fueur special offers lil^ W * - DEMS is a non-profit organization, depending on ' J voluntary offered assistance in time and material. ALL FOR THE L O V E D U K E !* O F Sponsors are welcomed. Address: Voort 18b, Meerle. Belgium - Telephone and Fax: +32 3 315 75 83 - E-mail: [email protected] LOS ANGELES ELLINGTON '2000 - By Roger Boyes The eighteenth international conference of the Kenny struck something of a sombre note, observing that Duke Ellington Study Group took place in the we’re all getting older, and urging on us the need for active effort Roosevelt Hotel, 7000 Hollywood Boulevard, Los to attract the younger recruits who will come after us. Angeles, from Wednesday to Sunday, 24-28 May This report isn't the place for pondering the future of either 2000. The Duke Ellington Society of Southern conferences or the wider activities of the Ellington Study Groups California were our hosts, and congratulations are due around the world. -

Between Friends

Friendships Between Men: Masculinity as a Relational Experience by Matthew L. Brooks A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Communication College of Arts and Sciences University of South Florida Major Professor: Arthur P. Bochner, Ph.D. Carolyn Ellis, Ph.D. Kenneth Cissna, Ph.D. Stacy Holman Jones, Ph.D. James King, Ph.D. Date of Approval: November 2, 2007 Keywords: Friendship, Masculinity, Autoethnography, Dialogue, Friendship as Method, Narrative © Copyright 2007, Matthew L. Brooks Dedication This dissertation is dedicated to my son. Acknowledgements I wish to thank my advisor, Art Bochner, without whom this dissertation would not have been concluded successfully and artfully. I also thank my committee members—Ken Cissna, Carolyn Ellis, Stacy Holman Jones, and Jim King—who lent creative and critical support along the way. My most gracious thanks to all my peers, whose conversation in the hallways between classes sustained me. Finally, to my best friend and wife, Kimberly, for always living with me through the pits and pinnacles of writing and researching; I love you. Contents Abstract iii Foreword 1 Chapter One: Necessary Baggage 17 Chapter Two: Details, Desire, Names 36 Chapter Three: Touched 48 Chapter Four: Hair, Muscles, and Orgasm 63 Chapter Five: Assuming Old Habits 86 Chapter Six: Opposites 121 Chapter Seven: No Method but the Self 139 Chapter Eight: Participant Monologues 167 Bert’s Monologue 167 Sidney’s Monologue 174 Kirk’s Monologue 181 Chapter -

Chance the Rapper's Creation of a New Community of Christian

Bates College SCARAB Honors Theses Capstone Projects 5-2020 “Your Favorite Rapper’s a Christian Rapper”: Chance the Rapper’s Creation of a New Community of Christian Hip Hop Through His Use of Religious Discourse on the 2016 Mixtape Coloring Book Samuel Patrick Glenn [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scarab.bates.edu/honorstheses Recommended Citation Glenn, Samuel Patrick, "“Your Favorite Rapper’s a Christian Rapper”: Chance the Rapper’s Creation of a New Community of Christian Hip Hop Through His Use of Religious Discourse on the 2016 Mixtape Coloring Book" (2020). Honors Theses. 336. https://scarab.bates.edu/honorstheses/336 This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Capstone Projects at SCARAB. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of SCARAB. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “Your Favorite Rapper’s a Christian Rapper”: Chance the Rapper’s Creation of a New Community of Christian Hip Hop Through His Use of Religious Discourse on the 2016 Mixtape Coloring Book An Honors Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Religious Studies Department Bates College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Arts By Samuel Patrick Glenn Lewiston, Maine March 30 2020 Acknowledgements I would first like to acknowledge my thesis advisor, Professor Marcus Bruce, for his never-ending support, interest, and positivity in this project. You have supported me through the lows and the highs. You have endlessly made sacrifices for myself and this project and I cannot express my thanks enough. -

OP 323 Sex Tips.Indd

BY PAUL MILES Copyright © 2010 Paul Miles This edition © 2010 Omnibus Press (A Division of Music Sales Limited) Cover and book designed by Fresh Lemon ISBN: 978.1.84938.404.9 Order No: OP 53427 The Author hereby asserts his/her right to be identified as the author of this work in accordance with Sections 77 to 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage or retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote brief passages. Exclusive Distributors Music Sales Limited, 14/15 Berners Street, London, W1T 3LJ. Music Sales Corporation, 257 Park Avenue South, New York, NY 10010, USA. Macmillan Distribution Services, 56 Parkwest Drive Derrimut, Vic 3030, Australia. Printed by: Gutenberg Press Ltd, Malta. A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. Visit Omnibus Press on the web at www.omnibuspress.com For more information on Sex Tips From Rock Stars, please visit www.SexTipsFromRockStars.com. Contents Introduction: Why Do Rock Stars Pull The Hotties? ..................................4 The Rock Stars ..........................................................................................................................................6 Beauty & Attraction .........................................................................................................................18 Clothing & Lingerie ........................................................................................................................35 -

Country Update

Country Update BILLBOARD.COM/NEWSLETTERS MARCH 1, 2021 | PAGE 1 OF 18 INSIDE BILLBOARD COUNTRY UPDATE [email protected] What’s Up With Strait Talk With Songwriter Dean Dillon Bryan’s ‘Down’ >page 4 As He Awaits His Hall Of Fame Induction Academy Of Country Life-changing moments are not always obvious at the time minutes,” says Dillon. “I was in shock. My life is racing through Music Awards they occur. my mind, you know? And finally, I said something stupid, like, Raise Diversity So it’s easy to understand how songwriter Dean Dillon (“Ten- ‘Well, I’ve given my life to country music.’ She goes, ‘Well, we >page 10 nessee Whiskey,” “The Chair”) missed the 40th anniversary know you have, and we’re just proud to tell you that you’re going of a turning point in his career in February. He and songwriter to be inducted next fall.’ ” Frank Dycus (“I Don’t Need Your Rockin’ Chair,” “Marina Del The pandemic screwed up those plans. Dillon couldn’t even Rey”) were sitting on the front porch at Dycus’ share his good fortune until August — “I was tired FGL, Lambert, Clark home/office on Music Row when producer Blake of keeping that a secret,” he says — and he’s still Get Musical Help Mevis (Keith Whitley, Vern Gosdin) pulled over waiting, likely until this fall, to enter the hall >page 11 at the curb and asked if they had any material. along with Marty Stuart and Hank Williams Jr. He was about to record a new kid and needed Joining with Bocephus is apropos: Dillon used some songs. -

Song Catalogue February 2020 Artist Title 2 States Mast Magan 2 States Locha E Ulfat 2 Unlimited No Limit 2Pac Dear Mama 2Pac Changes 2Pac & Notorious B.I.G

Song Catalogue February 2020 Artist Title 2 States Mast Magan 2 States Locha_E_Ulfat 2 Unlimited No Limit 2Pac Dear Mama 2Pac Changes 2Pac & Notorious B.I.G. Runnin' (Trying To Live) 2Pac Feat. Dr. Dre California Love 3 Doors Down Kryptonite 3Oh!3 Feat. Katy Perry Starstrukk 3T Anything 4 Non Blondes What's Up 5 Seconds of Summer Youngblood 5 Seconds of Summer She's Kinda Hot 5 Seconds of Summer She Looks So Perfect 5 Seconds of Summer Hey Everybody 5 Seconds of Summer Good Girls 5 Seconds of Summer Girls Talk Boys 5 Seconds of Summer Don't Stop 5 Seconds of Summer Amnesia 5 Seconds of Summer (Feat. Julia Michaels) Lie to Me 5ive When The Lights Go Out 5ive We Will Rock You 5ive Let's Dance 5ive Keep On Movin' 5ive If Ya Getting Down 5ive Got The Feelin' 5ive Everybody Get Up 6LACK Feat. J Cole Pretty Little Fears 7Б Молодые ветра 10cc The Things We Do For Love 10cc Rubber Bullets 10cc I'm Not In Love 10cc I'm Mandy Fly Me 10cc Dreadlock Holiday 10cc Donna 30 Seconds To Mars The Kill 30 Seconds To Mars Rescue Me 30 Seconds To Mars Kings And Queens 30 Seconds To Mars From Yesterday 50 Cent Just A Lil Bit 50 Cent In Da Club 50 Cent Candy Shop 50 Cent Feat. Eminem & Adam Levine My Life 50 Cent Feat. Snoop Dogg and Young Jeezy Major Distribution 101 Dalmatians (Disney) Cruella De Vil 883 Nord Sud Ovest Est 911 A Little Bit More 1910 Fruitgum Company Simon Says 1927 If I Could "Weird Al" Yankovic Men In Brown "Weird Al" Yankovic Ebay "Weird Al" Yankovic Canadian Idiot A Bugs Life The Time Of Your Life A Chorus Line (Musical) What I Did For Love A Chorus Line (Musical) One A Chorus Line (Musical) Nothing A Goofy Movie After Today A Great Big World Feat.