Shining the Spotlight on Movie Microbes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Using Concrete Scales: a Practical Framework for Effective Visual Depiction of Complex Measures Fanny Chevalier, Romain Vuillemot, Guia Gali

Using Concrete Scales: A Practical Framework for Effective Visual Depiction of Complex Measures Fanny Chevalier, Romain Vuillemot, Guia Gali To cite this version: Fanny Chevalier, Romain Vuillemot, Guia Gali. Using Concrete Scales: A Practical Framework for Effective Visual Depiction of Complex Measures. IEEE Transactions on Visualization and Computer Graphics, Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers, 2013, 19 (12), pp.2426-2435. 10.1109/TVCG.2013.210. hal-00851733v1 HAL Id: hal-00851733 https://hal.inria.fr/hal-00851733v1 Submitted on 8 Jan 2014 (v1), last revised 8 Jan 2014 (v2) HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Using Concrete Scales: A Practical Framework for Effective Visual Depiction of Complex Measures Fanny Chevalier, Romain Vuillemot, and Guia Gali a b c Fig. 1. Illustrates popular representations of complex measures: (a) US Debt (Oto Godfrey, Demonocracy.info, 2011) explains the gravity of a 115 trillion dollar debt by progressively stacking 100 dollar bills next to familiar objects like an average-sized human, sports fields, or iconic New York city buildings [15] (b) Sugar stacks (adapted from SugarStacks.com) compares caloric counts contained in various foods and drinks using sugar cubes [32] and (c) How much water is on Earth? (Jack Cook, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution and Howard Perlman, USGS, 2010) shows the volume of oceans and rivers as spheres whose sizes can be compared to that of Earth [38]. -

Biophilia, Gaia, Cosmos, and the Affectively Ecological

vital reenchantments Before you start to read this book, take this moment to think about making a donation to punctum books, an independent non-profit press, @ https://punctumbooks.com/support/ If you’re reading the e-book, you can click on the image below to go directly to our donations site. Any amount, no matter the size, is appreciated and will help us to keep our ship of fools afloat. Contri- butions from dedicated readers will also help us to keep our commons open and to cultivate new work that can’t find a welcoming port elsewhere. Our ad- venture is not possible without your support. Vive la Open Access. Fig. 1. Hieronymus Bosch, Ship of Fools (1490–1500) vital reenchantments: biophilia, gaia, cosmos, and the affectively ecological. Copyright © 2019 by Lauren Greyson. This work carries a Creative Commons BY-NC-SA 4.0 International license, which means that you are free to copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format, and you may also remix, transform and build upon the material, as long as you clearly attribute the work to the authors (but not in a way that suggests the authors or punctum books endorses you and your work), you do not use this work for commercial gain in any form whatsoever, and that for any remixing and transformation, you distribute your rebuild under the same license. http://creativecommons.org/li- censes/by-nc-sa/4.0/ First published in 2019 by punctum books, Earth, Milky Way. https://punctumbooks.com ISBN-13: 978-1-950192-07-6 (print) ISBN-13: 978-1-950192-08-3 (ePDF) lccn: 2018968577 Library of Congress Cataloging Data is available from the Library of Congress Editorial team: Casey Coffee and Eileen A. -

NCSA Access Magazine

CONTACTS NCSA Contacts Directory http://www.ncsa.uiuc.edu/Generai/NCSAContacts.html Allocations Education & Outreach Division Orders for Publications, http://www.ncsa.uiuc.edu/Generai/A IIocations/ApplyTop.html http://www.ncsa.uiuc.edu/edu/EduHome.html NCSA Software, and Multimedia Radha Nandkumar John Ziebarth, Associate Director http://www.ncsa.uiuc.edu/Pubs/ 217-244-0650 217-244-1961 TechResCatalog/TRC.TOC.html [email protected] [email protected] Debbie Shirley [email protected] Applications Division/Faculty Program Education http://www.ncsa.uiuc.ed u/Apps/Apps lntro.html Scott Lathrop Public Information Office Melanie Loots, Associate Director 217-244-1099 http://www.ncsa.uiuc.edu/General/ 217-244-2921 [email protected] PIO/NCSAinfo.html [email protected] i uc.edu John Melchi Outreach 217-244-3049 Al lison Clark (information) Alai na Kanfer 217-244-8195 fax 217-244-0768 217-244-0876 [email protected] [email protected] i uc.edu [email protected] Publications Group Visitors Program Training http://www.ncsa.uiuc.edu/Pubs/ jean Soliday http://www.ncsa.uiuc.edu/General/ Pubslntro.html 217-244-1972 Training/training_homepage.html Melissa Johnson [email protected] u Mary Bea Walker 217-244-0645 217-244-9883 melissaj@ncsa .uiuc.edu Computing & Communications Division mbwalker@ncsa .uiuc.edu http://www.ncsa.uiuc.edu/Generai/CC/CCHome.html Software Development Division Charles Catlett, Associate Director Industrial Program http ://www.ncsa.uiuc.edu/SDG/SDGintro.html 217-333-1163 http://www.ncsa.uiuc.edu/General/lndusProg/ joseph Hardin, Associate Director [email protected] lndProg.html 217-244-7802 John Stevenson, Corporate Officer hardin@ncsa .uiuc.edu Ken Sartain (i nformation) 217-244-0474 217-244-0103 [email protected] jae Allen (information) sartain@ ncsa.u iuc.edu 217-244-3364 Marketing Communications Division [email protected] Consulting Services http://www.ncsa.uiuc.edu/Generai/MarComm/ http://www.ncsa. -

![Archons (Commanders) [NOTICE: They Are NOT Anlien Parasites], and Then, in a Mirror Image of the Great Emanations of the Pleroma, Hundreds of Lesser Angels](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8862/archons-commanders-notice-they-are-not-anlien-parasites-and-then-in-a-mirror-image-of-the-great-emanations-of-the-pleroma-hundreds-of-lesser-angels-438862.webp)

Archons (Commanders) [NOTICE: They Are NOT Anlien Parasites], and Then, in a Mirror Image of the Great Emanations of the Pleroma, Hundreds of Lesser Angels

A R C H O N S HIDDEN RULERS THROUGH THE AGES A R C H O N S HIDDEN RULERS THROUGH THE AGES WATCH THIS IMPORTANT VIDEO UFOs, Aliens, and the Question of Contact MUST-SEE THE OCCULT REASON FOR PSYCHOPATHY Organic Portals: Aliens and Psychopaths KNOWLEDGE THROUGH GNOSIS Boris Mouravieff - GNOSIS IN THE BEGINNING ...1 The Gnostic core belief was a strong dualism: that the world of matter was deadening and inferior to a remote nonphysical home, to which an interior divine spark in most humans aspired to return after death. This led them to an absorption with the Jewish creation myths in Genesis, which they obsessively reinterpreted to formulate allegorical explanations of how humans ended up trapped in the world of matter. The basic Gnostic story, which varied in details from teacher to teacher, was this: In the beginning there was an unknowable, immaterial, and invisible God, sometimes called the Father of All and sometimes by other names. “He” was neither male nor female, and was composed of an implicitly finite amount of a living nonphysical substance. Surrounding this God was a great empty region called the Pleroma (the fullness). Beyond the Pleroma lay empty space. The God acted to fill the Pleroma through a series of emanations, a squeezing off of small portions of his/its nonphysical energetic divine material. In most accounts there are thirty emanations in fifteen complementary pairs, each getting slightly less of the divine material and therefore being slightly weaker. The emanations are called Aeons (eternities) and are mostly named personifications in Greek of abstract ideas. -

UC San Diego UC San Diego Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC San Diego UC San Diego Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title The science of the stars in Danzig from Rheticus to Hevelius / Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/7n41x7fd Author Jensen, Derek Publication Date 2006 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO THE SCIENCE OF THE STARS IN DANZIG FROM RHETICUS TO HEVELIUS A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in History (Science Studies) by Derek Jensen Committee in charge: Professor Robert S. Westman, Chair Professor Luce Giard Professor John Marino Professor Naomi Oreskes Professor Donald Rutherford 2006 The dissertation of Derek Jensen is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm: _________________________________________ _________________________________________ _________________________________________ _________________________________________ _________________________________________ Chair University of California, San Diego 2006 iii FOR SARA iv TABLE OF CONTENTS Signature Page........................................................................................................... iii Dedication ................................................................................................................. iv Table of Contents ...................................................................................................... v List of Figures .......................................................................................................... -

ASTR/GEOL 3300: ET Life • Logistics: – Your First Day? Pick up a Syllabus, Overview, Etc

ASTR/GEOL 3300: ET Life • Logistics: – Your first day? Pick up a syllabus, overview, etc. – www.boulder.swri.edu/~kwalsh/ASTR3300 • News: – Homework #1 next week • Plan for Today: – Scale of the Universe – Our place • Next time: Forming Stars and Planets Rebecca’s Office Hours • Office: E122 2:00-4:00 Monday and Wednesday Preliminary HW1 results Question Yes No Mars 22 33 Solar System 35 20 Galaxy 46 9 Universe 48 7 The Greeks Thales – First Greek Astronomer • ~600 BC • Actually asked questions: “What is the Universe made of” • Predicted an eclipse • Also.. Anaximander Pythagoras and Erastothenes Retrograde motion • http://mars.jpl.nasa.gov/allaboutmars/ nightsky/nightsky04/ Ptolemy What did the Greeks know • The planets, Sun and Moon move across the sky, – The Sun moves at a very regular rate, but the line it follows varies with season – The Moon moves at regular rate, and the line it follows is much more regular – Some planets always move the same direction (W-E), – Though others sometimes backtrack-retrograde motion • There were no tools capable of measure absolute sizes, or precise positions Copernicus • FINALLY…. Tycho SN 1572 Kepler Kepler’s 2nd Law Galileo Newton’s Principia • Explained general laws of motion – from which Keplers laws of planetary motion are natural consequences Scale of the Universe: Powers of 10 Scientific notation: • 101 = 10 • 102 = 100 • 103 = 1000 • 106 = 1,000,000 • 109 = 1,000,000,000 • 1011 = 100,000,000,000 • 100 = 1 • 10-1 = 0.1 • 10-2 = 0.01 • Also, common notation: • 1e9 = 109 Eames chair Powers of -

The Warped Ways of Cosmic Light

BIOLOGIE & MEDIZIN_Infektionsbiologie “Around that area there are indeed numerous small nebulous patches so close together that, upon seeing the region, one is positively startled by the strange appearance of this ‘nebula cluster’.” This was the sentiment expressed by Heidelberg-based astronomer Max Wolf in 1901 about the galaxy cluster in the constellation Coma Berenices. The cluster Abell 2218 presents a similar appearance to the viewer today on this image from the Hubble Space Telescope. The “strange appearance” – the many blue and orange arcs – owes, in this case, to the effect of a gravitational lens. PHYSICS & ASTRONOMY_Gravitational Lenses The Warped Ways of Cosmic Light Albert Einstein predicted them, modern giant telescopes detected them – and Klaus Dolag simulates them on a computer: gravitational lenses. The academic staff member at the Max Planck Institute for Astrophysics in Garching and at the University Observatory Munich uses this physical phenomenon to such ends as weighing galaxy clusters and probing that ominous substance known as dark matter. TEXT HELMUT HORNUNG he sky over Principe was a total eclipse of the Sun. The test was More recent analyses of Eddington’s cloudy and the mood in the simple: if a massive object bends space, findings show that the values measured camp on the coconut plan- then the Sun must also cause the pass- at that time did, indeed, correspond to tation had hit rock bottom. ing light from stars to deviate from its the prediction, but that they are appar- Having set out from Eng- straight course. In other words, the ently the result of an instrument error T land, the men had been traveling for points of light in the immediate vicin- of, as it so happens, the very same mag- weeks to reach the volcanic island in ity of the black Sun should be shifted nitude. -

Download Attachment

Planetarium Science Center newsletterth st 6 year | 1 edition Science For All! 1st SCHOOL SEMESTER 2012/13 In this edition... The Origins of the Four Elements 2 Four Elements: The Powers of the Four Elements 4 The Fifth Element on the Big Screen 5 By: Maissa Azab Journey to the Moon 6 Roots of Life Plasma: The Uncharted Element 7 The Four Elements; the Epitome of Life 8 The Elements’ Wrath 11 Here we start a new year for the PSC and how they can devastate life just as much as The Four Elements that Make Your Body 14 Newsletter; the fourth for the Newsletter as a they sustain it. Nano-Elements of Nature 16 popular science publication. In what has become In this new cycle, we re-introduce sections Lessons from the Lorax 17 a tradition, in the first issue of every new cycle, such as “ZoomTech”, where we discuss how Antimatter: Mirror of the Universe 18 we go back to the roots. Last year, we started by nanotechnology can change the four elements as we know them. In this issue, we also introduce The Marvels of the Elements 20 discussing Planet Earth; this year, we focus in this new sections and columns. In the newly-introduced Fire Breathing Dragons 22 issue on the classical Four Elements of Nature, which were the core of all humanities and sciences “Science in Sci-Fi” section, we have a column on for centuries, if not millennia of human history. the fantastical action motion picture “The Fifth Element”, and a fascinating film review on the Earth, Water, Air, and Fire are indeed the four surprisingly insightful animation movie “The Lorax”. -

Grade 5 – Unit 3 (39 Days) Words Important for This Unit Subject Specific Words Explain Explanation Area Denominator Equation

Franklin Township Public Schools Math Guidance Document Grade 5 – Unit 3 (39 Days) Words Important for this Unit Subject Specific Words Explain Explanation Area Denominator Equation Related Simplify Place Value Fraction Mixed number Improper fraction Numerator Divisor Digit Decimal Algorithm Dividend Quotient Factors Product 1 | P a g e Key: Major Clusters | Supporting | Additional Clusters | * Benchmarked Standard Franklin Township Public Schools Math Guidance Document Grade 5 – Unit 3 (39 Days) Topic & # Content Standards & Math Critical Knowledge & Skills Possible Resources & Activities Days Practices Add, 5.NBT.B.7. Add, subtract, Obj. We are learning to: Add, subtract, multiply, and -Example Multiplication Strategies Anchor Chart Subtract, multiply, and divide divide decimals to hundredths using concrete models -Example Standard Algorithm Anchor Chart Multiply & decimals to hundredths, or drawings and strategies based on place value, -Model adding, subtracting decimals using base-ten- Divide using concrete models or properties of operations, and/or the relationship pieces and the standard algorithm. Multi-Digit drawings and strategies between addition and subtraction; explain the -Model multiplying decimals using area models and the standard algorithm. Decimals: based on place value, reasoning used, relating the strategy to the written -Model dividing with decimals using area models. 12 days properties of operations, method. -IXL – Online Practice and/or the relationship -Learn Alberta – Addition and Subtraction of between addition and Essential Question: How does my knowledge of basic Decimals Lesson subtraction; relate the operations help me solve problems? -Learn Alberta – Multiplication and Division of strategy to a written Essential Question: What makes a strategy both Decimals Lesson method and explain the effective and efficient? -BBC Bitesize – Decimals Game reasoning used. -

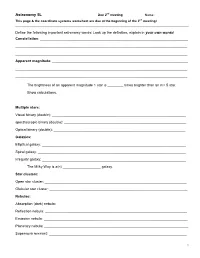

Astronomy 5L Due 2Nd Meeting Name : ______This Page & the Coordinate Systems Worksheet Are Due at the Beginning of the 2Nd Meeting!

Astronomy 5L Due 2nd meeting Name : _________________ This page & the coordinate systems worksheet are due at the beginning of the 2nd meeting! Define the following important astronomy words: Look up the definition, explain in your own words! Constellation: __________________________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________________________________ Apparent magnitude: ____________________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________________________________ The brightness of an apparent magnitude 1 star is ________ times brighter than an m= 5 star. Show calculations. Multiple stars: Visual binary (double): ___________________________________________________________________ spectroscopic binary (double): _____________________________________________________________ Optical binary (double): __________________________________________________________________ Galaxies: Elliptical galaxy: ________________________________________________________________________ Spiral galaxy: __________________________________________________________________________ Irregular galaxy: ________________________________________________________________________ The Milky Way is a(n) ___________________ galaxy. Star clusters: Open star cluster: _______________________________________________________________________ -

Butterflies Are Free to Fly

BUTTERFLIES ARE FREE TO FLY A New and Radical Approach To Spiritual Evolution By Stephen Davis Smashwords Edition, License Notes Thank you for downloading this free ebook. You are welcome to share it with your friends. This book may be reproduced, copied and distributed for non-commercial purposes, provided the book remains in its complete original form. Copyright 2010 by L & G Productions, LLC Table of Contents Chapter 0 – Introduction PART ONE – The Movie Theater Metaphor Preface to Part One Chapter 1 – Plato‟s Cave Chapter 2 – Joining Together Chapter 3 – What‟s Wrong with This Picture? Chapter 4 – The Library Chapter 5 – The Field Chapter 6 – The Hologram Chapter 7 – There is No “Out There” Out There Chapter 8 – The Breakout PART TWO – Inside the Cocoon Preface to Part Two Chapter 9 – The Consciousness Model Chapter 10 – The Player Model Chapter 11 – The Human Game Model Chapter 12 – The Two Halves Chapter 13 – The Process Chapter 14 – Spiritual Autolysis Chapter 15 – Detaching & “Desirelessness” Chapter 16 – Judgment Chapter 17 – Beliefs & Opinions Chapter 18 – Resistance Chapter 19 – Fear Chapter 20 – Who Am I? Chapter 21 – On Becoming a Butterfly PART THREE – Questions & Answers Preface to Part Three Chapter 22 – One Big Hologram? Chapter 23 – Other People Chapter 24 – The “Earth Environment” Template Chapter 25 – Are We All One? Chapter 26 – One Player per Infinite I? Chapter 27 – Past Lives? Chapter 28 – Karma, Cause & Effect Chapter 29 – Trust Chapter 30 – Money Chapter 31 – The Ego Chapter 32 – Compassion Chapter 33 – Robert Scheinfeld Chapter 34 – Jed McKenna Chapter 35 – U.G. Krishnamurti Chapter 36 – The Future You are invited to write a book review, or offer comments, or download the free audio book version of this ebook by visiting: ButterfliesFree.com CHAPTER 0 INTRODUCTION Back to the Table of Contents Sweet freedom whispered in my ear You're a butterfly And butterflies are free to fly Fly away, high away, bye bye ~ from Someone Saved my Life Tonight, music by Elton John, lyrics by Bernie Taupin George had a problem. -

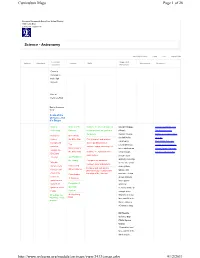

Page 1 of 26 Curriculum Maps 9/12/2011

Curriculum Maps Page 1 of 26 Kenmore-Tonawanda Union Free School District 1500 Colvin Blvd Buffalo, NY 14223-3119 Science - Astronomy Add to My ePortfolio Export Print Display Mode Essential Suggested Options Standards Content Skills Assessment Resources Questions Resources Green is common to both High Schools Blue is Kenmore East Red is Kenmore West Scale of the Universe and It's Origin What is Models of the Illustrate the inferred shape of Cosmic Voyage Astronomy 2009 Opening cosmology? Universe our galaxy and our position in (Video) Day Assignment.doc the galaxy. Cosmic Voyage Bill Nye Outer Space Video How does Our Galaxy, (An IMAX film Quiz.doc cosmic the Milky Way Plot, interpret, and analyze narrated by BlaineHubbleFotos.pps background data regarding Galactic The Leonard Nimoy), Cosmic Voyage Video.doc radiation distance and predicted speed. Dimensions of takes students on Cosmic Voyage Video.doc support the the Milky Way Illustrate the formation of the a trip through Nasascavengerhunt.doc Big-Bang solar system. through outer Theory? Our Position in space by focusing the Galaxy Compare the distances Why do on the size of our between stars and planets. astronomers Discovering solar system, Compare and contrast the theorize that Other Galaxies different theory models for the galaxy, and most of the formation of the Universe. universe. It also Classification matter in shows students of Galaxies galaxies and inner space - clusters of Formation of what can galaxies is dark Our Solar be found inside of matter? System a single atom. What does the The Big Bang Worksheet is true Model Big Bang Theory false and fill in the propose? blank - video is 45 minutes long.