Austronesian Linguistics at the 15Th Pacific Science Congress

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Palauan Language Report Carole Tiberius

Surrey Database of Agreement – Palauan Carole Tiberius Palauan Language Report Carole Tiberius 1 Introduction Palauan is a member of the Austronesian language family spoken in Palau. It has no close relatives within the Austronesian family. Palauan has about 17,000 speakers of whom about 80% live in the Republic of Palau. There is little dialectal variation (Georgopoulos 1991:21). This report draws heavily on Josephs’ (1975, 1997a, 1997b) Palauan grammar books. We are very grateful to him for his help and specialist advice. 2 Grammatical categories 2.1 T he Palauan words er, el, and a 2.1.1 The analysis of er Palauan has two words er (which are homonyms). Er can be a specifying word (indicated by SPEC in the glosses) or a relational word (indicated by REL in the glosses). The major function of the specifying word er is to distinguish specific objects from non-specific (general) ones. It marks a specific object noun phrase, but only when the verb is in the imperfective. For instance, (1a) A ngelek -ek a medakt a derumk PM child-1SG.POSS PM be.afraid PM thunder ‘My child is afraid of thunder.’ (1b) A ngelek -ek a medakt er a derumk PM child-1SG.POSS PM be.afraid SPEC PM thunder ‘My child is afraid of the thunder.’ (Josephs 1997a:74) As such, the presence of the specifying word er usually indicates a specific statement (as opposed to a general statement). In addition, er is sometimes used to distinguish between singular and plural with nonhuman object nouns, the presence of er marking the singular object as in the following example (Josephs 1997a:77): (2a) Ak ousbech er a ml-im el mo 1SG need SPEC PM car-2SG.POSS LINK go er a ocheraol SPEC PM money-raising.party ‘I need your car to go to the money-raising party.’ (2b) Ak ousbech a ml-im el mo 1.SG need PM car-2SG.POSS LINK go er a ocheraol SPEC PM money-raising.party ‘I need your cars to go to the money-raising party.’ 1 Surrey Database of Agreement – Palauan Carole Tiberius The relational word er, on the other hand, expresses certain types of relational phrases. -

Threatened Endemic Plants of Palau

THREA TENED ENDEMIC PLANTS OF PALAU BIODI VERSITY CONSERVATION LESSONS LEARNED TECHNICAL SERIES 19 BIODIVERSITY CONSERVATION LESSONS LEARNED TECHNICAL SERIES 19 Threatened Endemic Plants of Palau Biodiversity Conservation Lessons Learned Technical Series is published by: Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund (CEPF) and Conservation International Pacific Islands Program (CI-Pacific) PO Box 2035, Apia, Samoa T: + 685 21593 E: [email protected] W: www.conservation.org The Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund is a joint initiative of l’Agence Française de Développement, Conservation International, the Global Environment Facility, the Government of Japan, the MacArthur Foundation and the World Bank. A fundamental goal is to ensure civil society is engaged in biodiversity conservation. Conservation International Pacific Islands Program. 2013. Biodiversity Conservation Lessons Learned Technical Series 19: Threatened Endemic Plants of Palau. Conservation International, Apia, Samoa Authors: Craig Costion, James Cook University, Australia Design/Production: Joanne Aitken, The Little Design Company, www.thelittledesigncompany.com Photo credits: Craig Costion (unless cited otherwise) Cover photograph: Parkia flowers. © Craig Costion Series Editors: Leilani Duffy, Conservation International Pacific Islands Program Conservation International is a private, non-profit organization exempt from federal income tax under section 501c(3) of the Internal Revenue Code. OUR MISSION Building upon a strong foundation of science, partnership and field demonstration, -

Austronesian Diaspora a New Perspective

AUSTRONESIAN DIASPORA A NEW PERSPECTIVE Proceedings the International Symposium on Austronesian Diaspora AUSTRONESIAN DIASPORA A NEW PERSPECTIVE Proceedings the International Symposium on Austronesian Diaspora PERSPECTIVE 978-602-386-202-3 Gadjah Mada University Press Jl. Grafika No. 1 Bulaksumur Yogyakarta 55281 Telp./Fax.: (0274) 561037 [email protected] | ugmpress.ugm.ac.id Austronesian Diaspora PREFACE OF PUBLISHER This book is a proceeding from a number of papers presented in The International Symposium on Austronesian Diaspora on 18th to 23rd July 2016 at Nusa Dua, Bali, which was held by The National Research Centre of Archaeology in cooperation with The Directorate of Cultural Heritage and Museums. The symposium is the second event with regard to the Austronesian studies since the first symposium held eleven years ago by the Indonesian Institute of Sciences in cooperation with the International Centre for Prehistoric and Austronesia Study (ICPAS) in Solo on 28th June to 1st July 2005 with a theme of “the Dispersal of the Austronesian and the Ethno-geneses of People in the Indonesia Archipelago’’ that was attended by experts from eleven countries. The studies on Austronesia are very interesting to discuss because Austronesia is a language family, which covers about 1200 languages spoken by populations that inhabit more than half the globe, from Madagascar in the west to Easter Island (Pacific Area) in the east and from Taiwan-Micronesia in the north to New Zealand in the south. Austronesia is a language family, which dispersed before the Western colonization in many places in the world. The Austronesian dispersal in very vast islands area is a huge phenomenon in the history of humankind. -

Stau D E Et a L . / Meta Mo Rp H O Sis 31 (3 ): 1 – 3 8 0

Noctuoidea: Erebidae: Aganainae, Anobinae, Arctiinae Date of Host species Locality collection (c), Ref. no. Lepidoptera species Rearer Final instar larva Adult (Family) pupation (p), emergence (e) Erebidae: Aganainae M1637 Asota speciosa Ficus sur Jongmansspruit; c 13.1.2017 A. & I. Sharp (Moraceae) Hoedspruit; p 13.1.2017 Limpopo; e 26.1.2017 South Africa AM113 Asota speciosa Ficus natalensis Kameelfontein, farm; c 23.11.2017 A. & I. Sharp (Moraceae) Pretoria; p 1.12.2017 Gauteng; e 18.12.2017 South Africa Staude M1699 Asota speciosa Ficus sycamorus Epsom (North); c 5.4.2017 A. & I. Sharp (Moraceae) Hoedspruit; p 15.4.2017 et al Limpopo; e 25.10.2017 . South Africa / Metamorphosis L20180331-1V Asota speciosa Ficus sp. Wilderness; c 31.3.2018 J. Balona (Moraceae) Hoekwil; p 9.4.2018 Western Cape; e 22.5.2018 South Africa 31 (3) : 1 ‒ 380 MJB052 Asota speciosa Ficus sur St Lucia; c 9.12.2018 M. J. Botha (Moraceae) KwaZulu-Natal; p 18.12.2018 South Africa e 2.1.2019 138 Noctuoidea: Erebidae: Aganainae, Anobinae, Arctiinae SBR014 Asota speciosa Ficus sur Westville; c 14.1.2018 S. Bradley (Moraceae) Durban; p 16.1.2018 KwaZulu-Natal; e 31.1.2018 South Africa M1832 Digama aganais Carissa edulis Jongmansspruit; c 14.6.2017 A. & I. Sharp (Apocynaceae) Hoedspruit; p 25.6.2017 Limpopo; e 18.7.2017 South Africa M1861 Digama aganais Carissa edulis Glen Lyden (Franklyn c 23.9.2017 A. & I. Sharp (Apocynaceae) Park); p 30.9.2017 Staude Kampersrus; e 14.10.2017 Mpumalanga; South Africa et al . -

“There Is No Place Like Home”

stephanie walda-mandel “There is no place Migration and Cultural Identity like home” of the Sonsorolese, Micronesia HEIDELBERG STUDIES IN PACIFIC ANTHROPOLOGY 5 heidelberg studies in pacific anthropology Volume 5 Edited by jürg wassmann stephanie walda-mandel “T here is no place like home” Migration and Cultural Identity of the Sonsorolese, Micronesia Universitätsverlag winter Heidelberg Bibliografische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliografie; detaillierte bibliografische Daten sind im Internet über http://dnb.d-nb.de abrufbar. Diese Veröffentlichung wurde als Dissertation im Jahr 2014 unter dem Titel “There’s No Place Like Home”: Auswirkungen von Migration auf die kulturelle Identität von Sonsorolesen im Fach Ethnologie an der Fakultät für Verhaltens- und Empirische Kulturwissenschaften der Ruprecht-Karls-Universität Heidelberg angenommen. cover: Father and son on the way to Sonsorol © S. Walda-Mandel 2004 isbn 978-3-8253-6692-6 Dieses Werk einschließlich aller seiner Teile ist urheberrechtlich geschützt. Jede Verwertung außerhalb der engen Grenzen des Urheberrechtsgesetzes ist ohne Zustimmung des Verlages unzulässig und strafbar. Das gilt ins- besondere für Vervielfältigungen, Übersetzungen, Mikroverfilmungen und die Einspeicherung und Verarbeitung in elektronischen Systemen. © 2016 Universitätsverlag Winter GmbH Heidelberg Imprimé en Allemagne · Printed in Germany Umschlaggestaltung: Klaus Brecht GmbH, Heidelberg Druck: Memminger MedienCentrum, -

South Africa's Drakensberg Mountains & Zululand

CRANE'S CAPE TOURS & TRAVEL P.O.BOX 26277 * HOUT BAY * 7872 CAPE TOWN * SOUTH AFRICA TEL / FAX: (021) 790 5669 CELL: 083 65 99 777 E-Mail: [email protected] Drakensberg Mountains and Zululand 26 January – 10 February 2017 Holiday participants John and Jan Croft Malcolm and Helen Crowder Peter and Monica Douch Barbara Wheeler Helen Young David and Barbara Lovell John Coish Jean Dunn Chris Durdin and John Durdin Leaders: Geoff Crane and Bruce Terlien www.naturalhistorytours.co.za Holiday report by Chris Durdin. All the photos in this report were taken during the holiday by group members. Cover: top row – red bishop and elephant parade at Hluhluwe-Imfolozi Game Park (JCr). Middle row – Common diadem ♂ (JCr); vervet monkey and butterfly lobelia (BL). Bottom row – Black-bellied starling and male impalas (JCr). More photos from the holiday are via www.honeyguide.co.uk/wildlife-holidays/drakenbergandzululand.html We stayed at Drakensbergs: Mont Aux Sources hotel www.montauxsources.co.za Bonamanzi Game Reserve www.bonamanzi.co.uk Wakkerstroom: Wetlands Guest House www.wetlandscountryhouse.co.za and De Kotzenhof Guest House www.dekotzenhof.co.uk The group in Hluhluwe-Imfolozi Game Park, with elephants in the background. Peter and Monica were elsewhere when the photo was taken by Geoff, so he is also missing. This holiday, as for every Honeyguide holiday, also puts something into conservation in our host country by way of a contribution to the wildlife that we enjoyed. The conservation contributions this year of £40 per person were supplemented by gift aid through the Honeyguide Wildlife Charitable Trust giving a total of £630, a little over 10,250 rands, sent to the second Southern African Bird Atlas Project (SABAP2), an intensive monitoring programme undertaken in South Africa and adjacent countries. -

Cultural Mapping— Republic of Palau

Cultural Mapping— Republic of Palau Cultural Mapping– Republic of Palau By Ann Kloulechad-Singeo Published by the Secretariat of the Pacific Community on behalf of the Ministry of Culture and Community Affairs, Government of the Republic of Palau Republic of Palau, 2011 © Copyright Secretariat of the Pacific Community (SPC) and the Ministry of Culture and Community Affairs, Government of the Republic of Palau, 2011 All rights for commercial / for profit reproduction or translation, in any form, reserved. SPC authorizes the partial reproduction or translation of this material for scientific, educational or research purposes, provided that SPC and the source document are properly acknowledged. Permission to reproduce the document and/or translate in whole, in any form, whether for commercial / for profit or non-profit purposes, must be requested in writing. Original SPC artwork may not be altered or separately published without permission. Original text: English Secretariat of the Pacific Community Cataloguing-in-publication data Kloulechad-Singeo, Ann Cultural mapping: Republic of Palau / by Ann Kloulechad-Singeo 1. Cultural property — Palau. 2. Cultural policy — Palau. 3. Culture diffusion — Palau. I. Kloulechad-Singeo, Ann II. Secretariat of the Pacific Community III. Palau. Ministry of Community and Cultural Affairs 344.09966 AACR2 ISBN: 978-982-00-0514-3 Cover photo: Delerrok money purse crafted by Ngrasuong Techur. The money purse is protected under the copyright laws of Palau. Photo taken by Bureau of Arts and Culture, Palau. Contents -

The Coastal Marind Language

This document is downloaded from DR‑NTU (https://dr.ntu.edu.sg) Nanyang Technological University, Singapore. The coastal marind language Olsson, Bruno 2018 Olsson, B. (2018). The coastal marind language. Doctoral thesis, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore. http://hdl.handle.net/10356/73235 https://doi.org/10.32657/10356/73235 Downloaded on 01 Oct 2021 11:12:23 SGT THE COASTAL MARIND LANGUAGE BRUNO OLSSON SCHOOL OF HUMANITIES 2017 The Coastal Marind language Bruno Olsson School of Humanities A thesis submitted to the Nanyang Technological University in partial fulfilment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2017 List of abbreviations. Gloss Label Explanation (m) Malay/Indonesian word 1, 2, 3 1st, 2nd 3rd person sg, pl singular, plural 2|3 2nd or 3rd person I, II, III, IV Genders I, II, III and IV Chapter 6 3pl>1 3pl Actor acts on 1st person §8.2.2.2 a Actor §8.2 acpn Accompaniment §12.2 act Actualis §14.3.1 aff Affectionate §14.3.3 all Allative §12.3 apl Associative plural §5.4.2 cont Continuative §13.2.4 ct Contessive §14.4.5 ctft Counterfactual §13.3 dat Dative §8.3 dep Dependent dir Directional Orientation §10.1.4 dist Distal §3.3.2.1 dur Past Durative §13.2.1 ext Extended §13.2.3 frus Frustrative §14.4.1 fut Future §13.2.7 fut2 2nd Future §13.2.7 gen Genitive §8.4 giv Given §14.1 hab Habitual §13.2.6 hort Hortative §17.1.3 slf.int Self-interrogative §14.3.4 imp Imperative §17.1.1 iness Inessive §9.3.2 ingrs Ingressive §16.3.5 int Interrogative §17.3.1 Continued on next page. -

ISO 639-3 New Code Request

ISO 639-3 Registration Authority Request for New Language Code Element in ISO 639-3 This form is to be used in conjunction with a “Request for Change to ISO 639-3 Language Code” form Date: 2012-6-27 Name of Primary Requester: Brian Paris E-mail address: lr-socioling at sil dot org dot pg Names, affiliations and email addresses of additional supporters of this request: John Brownie SIL-PNG Sociolingistic Consultant: lr-socioling at sil dot org dot pg Associated Change request number : 2012-141 (completed by Registration Authority) Tentative assignment of new identifier : hrc (completed by Registration Authority) PLEASE NOTE: This completed form will become part of the public record of this change request and the history of the ISO 639-3 code set. Use Shift-Enter to insert a new line in a form field (where allowed). 1. NAMES and IDENTIFICATION a) Preferred name of language for code element denotation: Niwer Mil b) Autonym (self-name) for this language: c) Common alternate names and spellings of language, and any established abbreviations: Tangga d) Reason for preferred name: This is the name the people use for themselves and their language. e) Name and approximate population of ethnic group or community who use this language (complete individual language currently in use): Niwer Mil 6300 (2000 National Census) f) Preferred three letter identifier, if available: hrc Your suggestion will be taken into account, but the Registration Authority will determine the identifier to be proposed. The identifiers is not intended to be an abbreviation for a name of the language, but to serve as a device to identify a given language uniquely. -

GOO-80-02119 392P

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 228 863 FL 013 634 AUTHOR Hatfield, Deborah H.; And Others TITLE A Survey of Materials for the Study of theUncommonly Taught Languages: Supplement, 1976-1981. INSTITUTION Center for Applied Linguistics, Washington, D.C. SPONS AGENCY Department of Education, Washington, D.C.Div. of International Education. PUB DATE Jul 82 CONTRACT GOO-79-03415; GOO-80-02119 NOTE 392p.; For related documents, see ED 130 537-538, ED 132 833-835, ED 132 860, and ED 166 949-950. PUB TYPE Reference Materials Bibliographies (131) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC16 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Annotated Bibliographies; Dictionaries; *InStructional Materials; Postsecondary Edtmation; *Second Language Instruction; Textbooks; *Uncommonly Taught Languages ABSTRACT This annotated bibliography is a supplement tothe previous survey published in 1976. It coverslanguages and language groups in the following divisions:(1) Western Europe/Pidgins and Creoles (European-based); (2) Eastern Europeand the Soviet Union; (3) the Middle East and North Africa; (4) SouthAsia;(5) Eastern Asia; (6) Sub-Saharan Africa; (7) SoutheastAsia and the Pacific; and (8) North, Central, and South Anerica. The primaryemphasis of the bibliography is on materials for the use of theadult learner whose native language is English. Under each languageheading, the items are arranged as follows:teaching materials, readers, grammars, and dictionaries. The annotations are descriptive.Whenever possible, each entry contains standardbibliographical information, including notations about reprints and accompanyingtapes/records -

Metamorphosis Issn 1018–6490 (Print) Lepidopterists’ Society of Africa Issn 2307–5031 (Online)

Volume 30: 55–57 METAMORPHOSIS ISSN 1018–6490 (PRINT) LEPIDOPTERISTS’ SOCIETY OF AFRICA ISSN 2307–5031 (ONLINE) Publications on Afrotropical Lepidoptera during 2019 Published online: 30 December 2019 Mark C. Williams 183 van der Merwe Street, Rietondale 0084, Pretoria, South Africa. E-mail: [email protected] Copyright © Lepidopterists’ Society of Africa Abstract: The articles published since the author’s Publications on Afrotropical Lepidoptera during 2017-2018, which deal with scientific research into Afrotropical Lepidoptera, are listed alphabetically by author. Articles dealing with control of Lepidoptera as pests are excluded. Citation: Williams, M.C. 2019. Publications on Afrotropical Lepidoptera during 2019. Metamorphosis 30: 55–57. PUBLICATIONS genus Leptotes (Lepidoptera: Lycaenidae). Systematic Entomology 44: 652–665. AGASSIZ, D.J.L. 2019. MONOGRAPH: The GAIGHER, R., PRYKE, J.S. & SAMWAYS, M.J. 2019. Yponomeutidae of the Afrotropical region Divergent fire management leads to multiple beneficial (Lepidoptera: Yponomeutoidea). Zootaxa 4600 (1): outcomes for butterfly conservation in a production 001–069. mosaic. Journal of Applied Ecology 2019:1–11. AMIET, J-L. 2019. Histoire naturelle des papillons du GREHAN, J.R., RALSTON, C.D. & VAN NOORT, S. Cameroun. Les premiers etats de Limenitines. Nyons: 2019. Specialized wing scales in the male of the South J-L Amiet; Chataulini: Locus solus. 340 pp. African moth Leto venus (Cramer, 1780) (Lepidoptera: BAYLISS, J., BRATTSTRÖM, BAMPTON, I. (†) & Hepialidae). Metamorphosis 30: 43–45. COLLINS, S. 2019. A new species of Leptomyrina HACKER, H. H., FIEBIG, R., GOATER, B., Butler, 1898 (Lepidoptera: Lycaenidae) from Mts SALDAITIS, A., SCHREIER, H. & STADIE, D. 2019. Mecula, Namuli, Inago, Nallume and Mabu in Northern Moths of Africa, Volume 1, Biogeography, Mozambique. -

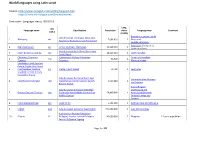

World Languages Using Latin Script

World languages using Latin script Source: http://www.omniglot.com/writing/langalph.htm https://www.ethnologue.com/browse/names Sort order : Language status, ISO 639-3 Lang, ISO Language name Classification Population status Language map Comment 639-3 (EGIDS) Botswana, Lesotho, South Indo-European, Germanic, West, Low 1. Afrikaans, afr 7,096,810 1 Africa and Saxon-Low Franconian, Low Franconian SwazilandNamibia Azerbaijan,Georgia,Iraq 2. Azeri,Azerbaijani azj Turkic, Southern, Azerbaijani 24,226,940 1 Jordan and Syria Indo-European Balto-Slavic Slavic West 3. Czech Bohemian Cestina ces 10,619,340 1 Czech Republic Czech-Slovak Chamorro,Chamorru Austronesian Malayo-Polynesian Guam and Northern 4. cha 94,700 1 Tjamoro Chamorro Mariana Islands Seychelles Creole,Seselwa Creole, Creole, Ilois, Kreol, 5. Kreol Seselwa, Seselwa, crs Creole, French based 72,700 1 Seychelles Seychelles Creole French, Seychellois Creole Indo-European Germanic North East Denmark Finland Norway 6. DanishDansk Rigsdansk dan Scandinavian Danish-Swedish Danish- 5,520,860 1 and Sweden Riksmal Danish AustriaBelgium Indo-European Germanic West High Luxembourg and 7. German Deutsch Tedesco deu German German Middle German East 69,800,000 1 NetherlandsDenmark Middle German Finland Norway and Sweden 8. Estonianestieesti keel ekk Uralic Finnic 1,132,500 1 Estonia Latvia and Lithuania 9. English eng Indo-European Germanic West English 341,000,000 1 over 140 countries Austronesian Malayo-Polynesian 10. Filipino fil Philippine Greater Central Philippine 45,000,000 1 Filippines L2 users population Central Philippine Tagalog Page 1 of 48 World languages using Latin script Lang, ISO Language name Classification Population status Language map Comment 639-3 (EGIDS) Denmark Finland Norway 11.