Pounamu, Notes on New Zealand Greenstone

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Unsettling a Settler Family's History in Aotearoa New Zealand

genealogy Article A Tale of Two Stories: Unsettling a Settler Family’s History in Aotearoa New Zealand Richard Shaw Politics Programme, Massey University, PB 11 222 Palmerston North, New Zealand; [email protected]; Tel.: +64-27609-8603 Abstract: On the morning of the 5 November 1881, my great-grandfather stood alongside 1588 other military men, waiting to commence the invasion of Parihaka pa,¯ home to the great pacifist leaders Te Whiti o Rongomai and Tohu Kakahi¯ and their people. Having contributed to the military campaign against the pa,¯ he returned some years later as part of the agricultural campaign to complete the alienation of Taranaki iwi from their land in Aotearoa New Zealand. None of this detail appears in any of the stories I was raised with. I grew up Pakeh¯ a¯ (i.e., a descendant of people who came to Aotearoa from Europe as part of the process of colonisation) and so my stories tend to conform to orthodox settler narratives of ‘success, inevitability, and rights of belonging’. This article is an attempt to right that wrong. In it, I draw on insights from the critical family history literature to explain the nature, purposes and effects of the (non)narration of my great-grandfather’s participation in the military invasion of Parihaka in late 1881. On the basis of a more historically comprehensive and contextualised account of the acquisition of three family farms, I also explore how the control of land taken from others underpinned the creation of new settler subjectivities and created various forms of privilege that have flowed down through the generations. -

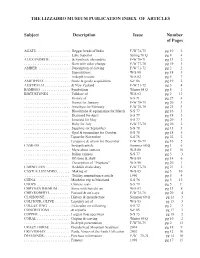

List of Articles

THE LIZZADRO MUSEUM PUBLICATION INDEX OF ARTICLES Subject Description Issue Number of Pages AGATE. .. Beggar beads of India F-W 74-75 pg 10 2 . Lake Superior Spring 70 Q pg 8 4 ALEXANDRITE . & Synthetic alexandrite F-W 70-71 pg 13 2 . Gem with color change F-W 77-78 pg 19 1 AMBER . Description of carving F-W 71-72 pg 2 2 . Superstitions W-S 80 pg 18 5 . in depth treatise W-S 82 pg 5 7 AMETHYST . Stone & geode acquisitions S-F 86 pg 19 2 AUSTRALIA . & New Zealand F-W 71-72 pg 3 4 BAMBOO . Symbolism Winter 68 Q pg 8 1 BIRTHSTONES . Folklore of W-S 93 pg 2 13 . History of S-S 71 pg 27 4 . Garnet for January F-W 78-79 pg 20 3 . Amethyst for February F-W 78-79 pg 22 3 . Bloodstone & aquamarine for March S-S 77 pg 16 3 . Diamond for April S-S 77 pg 18 3 . Emerald for May S-S 77 pg 20 3 . Ruby for July F-W 77-78 pg 20 2 . Sapphire for September S-S 78 pg 15 3 . Opal & tourmaline for October S-S 78 pg 18 5 . Topaz for November S-S 78 pg 22 2 . Turquoise & zircon for December F-W 78-79 pg 16 5 CAMEOS . In-depth article Summer 68 Q pg 1 6 . More about cameos W-S 80 pg 5 10 . Italian cameos S-S 77 pg 3 3 . Of stone & shell W-S 89 pg 14 6 . Description of “Neptune” W-S 90 pg 20 1 CARNELIAN . -

92467102. Robertson

Edinburgh Research Explorer Chapter 15:Construction of a Paleozoic–Mesozoic accretionary orogen along the active continental margin of SE Gondwana (South Island, New Zealand): summary and overview Citation for published version: Robertson, AHF, Campbell, HJ, Johnston, MR & Palamakumbra, R 2019, Chapter 15:Construction of a Paleozoic–Mesozoic accretionary orogen along the active continental margin of SE Gondwana (South Island, New Zealand): summary and overview. in Introduction to Paleozoic–Mesozoic geology of South Island, New Zealand: subduction-related processes adjacent to SE Gondwana . 1 edn, vol. 49, Geological Society Memoir, Geological Society of London, pp. 331-372. https://doi.org/10.1144/M49.8 Digital Object Identifier (DOI): 10.1144/M49.8 Link: Link to publication record in Edinburgh Research Explorer Document Version: Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Published In: Introduction to Paleozoic–Mesozoic geology of South Island, New Zealand: subduction-related processes adjacent to SE Gondwana Publisher Rights Statement: ©2019TheAuthor(s).ThisisanOpenAccessarticledistributedunderthetermsoftheCreativeCommonsAttribution4.0Li cense(http://creativecommons.org/ licenses/by/4.0/). Published by The Geological Society of London. Publishing disclaimer: www.geolsoc.org.uk/pub_ethics General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Edinburgh Research Explorer is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The University of Edinburgh has made every reasonable effort to ensure that Edinburgh Research Explorer content complies with UK legislation. If you believe that the public display of this file breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. -

Using Te Reo Māori and Ta Re Moriori in Taxonomy

VealeNew Zealand et al.: Te Journal reo Ma- oriof Ecologyin taxonomy (2019) 43(3): 3388 © 2019 New Zealand Ecological Society. 1 REVIEW Using te reo Māori and ta re Moriori in taxonomy Andrew J. Veale1,2* , Peter de Lange1 , Thomas R. Buckley2,3 , Mana Cracknell4, Holden Hohaia2, Katharina Parry5 , Kamera Raharaha-Nehemia6, Kiri Reihana2 , Dave Seldon2,3 , Katarina Tawiri2 and Leilani Walker7 1Unitec Institute of Technology, 139 Carrington Road, Mt Albert, Auckland 1025, New Zealand 2Manaaki Whenua - Landcare Research, 231 Morrin Road, St Johns, Auckland 1072, New Zealand 3School of Biological Sciences, University of Auckland, 3A Symonds St, Auckland CBD, Auckland 1010, New Zealand 4Rongomaiwhenua-Moriori, Kaiangaroa, Chatham Island, New Zealand 5Massey University, Private Bag 11222 Palmerston North, 4442, New Zealand 6Ngāti Kuri, Otaipango, Ngataki, Te Aupouri, Northland, New Zealand 7Auckland University of Technology, 55 Wellesley St E, Auckland CBS, Auckland 1010, New Zealand *Author for correspondence (Email: [email protected]) Published online: 28 November 2019 Auheke: Ko ngā ingoa Linnaean ka noho hei pou mō te pārongo e pā ana ki ngā momo koiora. He mea nui rawa kia mārama, kia ahurei hoki ngā ingoa pūnaha whakarōpū. Me pēnei kia taea ai te whakawhitiwhiti kōrero ā-pūtaiao nei. Nā tēnā kua āta whakatakotohia ētahi ture, tohu ārahi hoki hei whakahaere i ngā whakamārama pūnaha whakarōpū. Kua whakamanahia ēnei kia noho hei tikanga mō te ao pūnaha whakarōpū. Heoi, arā noa atu ngā hua o te tukanga waihanga ingoa Linnaean mō ngā momo koiora i tua atu i te tautohu noa i ngā momo koiora. Ko tētahi o aua hua ko te whakarau: (1) i te mātauranga o ngā iwi takatake, (2) i te kōrero rānei mai i te iwi o te rohe, (3) i ngā kōrero pūrākau rānei mō te wāhi whenua. -

A Mat of Serpents: Aztec Strategies of Control from an Empire in Decline

A Mat of Serpents: Aztec Strategies of Control from an Empire in Decline Jerónimo Reyes On my honor, Professors Andrea Lepage and Elliot King mark the only aid to this thesis. “… the ruler sits on the serpent mat, and the crown and the skull in front of him indicate… that if he maintained his place on the mat, the reward was rulership, and if he lost control, the result was death.” - Aztec rulership metaphor1 1 Emily Umberger, " The Metaphorical Underpinnings of Aztec History: The Case of the 1473 Civil War," Ancient Mesoamerica 18, 1 (2007): 18. I dedicate this thesis to my mom, my sister, and my brother for teaching me what family is, to Professor Andrea Lepage for helping me learn about my people, to Professors George Bent, and Melissa Kerin for giving me the words necessary to find my voice, and to everyone and anyone finding their identity within the self and the other. Table of Contents List of Illustrations ………………………………………………………………… page 5 Introduction: Threads Become Tapestry ………………………………………… page 6 Chapter I: The Sum of its Parts ………………………………………………… page 15 Chapter II: Commodification ………………………………………………… page 25 Commodification of History ………………………………………… page 28 Commodification of Religion ………………………………………… page 34 Commodification of the People ………………………………………… page 44 Conclusion ……………………………………………………………………... page 53 Illustrations ……………………………………………………………………... page 54 Appendices ……………………………………………………………………... page 58 Bibliography ……………………………………………………………………... page 60 …. List of Illustrations Figure 1: Statue of Coatlicue, Late Period, 1439 (disputed) Figure 2: Peasant Ritual Figurines, Date Unknown Figure 3: Tula Warrior Figure Figure 4: Mexica copy of Tula Warrior Figure, Late Aztec Period Figure 5: Coyolxauhqui Stone, Late Aztec Period, 1473 Figure 6: Male Coyolxauhqui, carving on greenstone pendant, found in cache beneath the Coyolxauhqui Stone, Date Unknown Figure 7: Vessel with Tezcatlipoca Relief, Late Aztec Period, ca. -

The Colonial Reinvention of the Hei Tiki: Pounamu, Knowledge and Empire, 1860S-1940S

The Colonial Reinvention of the Hei Tiki: Pounamu, Knowledge and Empire, 1860s-1940s Kathryn Street A thesis submitted to Victoria University of Wellington in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History Victoria University of Wellington Te Whare Wānanga o te Ūpoko o te Ika a Māui 2017 Abstract This thesis examines the reinvention of pounamu hei tiki between the 1860s and 1940s. It asks how colonial culture was shaped by engagement with pounamu and its analogous forms greenstone, nephrite, bowenite and jade. The study begins with the exploitation of Ngāi Tahu’s pounamu resource during the West Coast gold rush and concludes with post-World War II measures to prohibit greenstone exports. It establishes that industrially mass-produced pounamu hei tiki were available in New Zealand by 1901 and in Britain by 1903. It sheds new light on the little-known German influence on the commercial greenstone industry. The research demonstrates how Māori leaders maintained a degree of authority in the new Pākehā-dominated industry through patron-client relationships where they exercised creative control. The history also tells a deeper story of the making of colonial culture. The transformation of the greenstone industry created a cultural legacy greater than just the tangible objects of trade. Intangible meanings are also part of the heritage. The acts of making, selling, wearing, admiring, gifting, describing and imagining pieces of greenstone pounamu were expressions of culture in practice. Everyday objects can tell some of these stories and provide accounts of relationships and ways of knowing the world. The pounamu hei tiki speaks to this history because more than merely stone, it is a cultural object and idea. -

The Bilimek Pulque Vessel (From in His Argument for the Tentative Date of 1 Ozomatli, Seler (1902-1923:2:923) Called Atten- Nicholson and Quiñones Keber 1983:No

CHAPTER 9 The BilimekPulqueVessel:Starlore, Calendrics,andCosmologyof LatePostclassicCentralMexico The Bilimek Vessel of the Museum für Völkerkunde in Vienna is a tour de force of Aztec lapidary art (Figure 1). Carved in dark-green phyllite, the vessel is covered with complex iconographic scenes. Eduard Seler (1902, 1902-1923:2:913-952) was the first to interpret its a function and iconographic significance, noting that the imagery concerns the beverage pulque, or octli, the fermented juice of the maguey. In his pioneering analysis, Seler discussed many of the more esoteric aspects of the cult of pulque in ancient highland Mexico. In this study, I address the significance of pulque in Aztec mythology, cosmology, and calendrics and note that the Bilimek Vessel is a powerful period-ending statement pertaining to star gods of the night sky, cosmic battle, and the completion of the Aztec 52-year cycle. The Iconography of the Bilimek Vessel The most prominent element on the Bilimek Vessel is the large head projecting from the side of the vase (Figure 2a). Noting the bone jaw and fringe of malinalli grass hair, Seler (1902-1923:2:916) suggested that the head represents the day sign Malinalli, which for the b Aztec frequently appears as a skeletal head with malinalli hair (Figure 2b). However, because the head is not accompanied by the numeral coefficient required for a completetonalpohualli Figure 2. Comparison of face date, Seler rejected the Malinalli identification. Based on the appearance of the date 8 Flint on front of Bilimek Vessel with Aztec Malinalli sign: (a) face on on the vessel rim, Seler suggested that the face is the day sign Ozomatli, with an inferred Bilimek Vessel, note malinalli tonalpohualli reference to the trecena 1 Ozomatli (1902-1923:2:922-923). -

An Osteological Analysis of Human Remains From

AN OSTEOLOGICAL ANALYSIS OF HUMAN REMAINS FROM CUSIRISNA CAVE, NICARAGUA by Kendra L. Philmon A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Dorothy F. Schmidt College of Arts and Letters in Partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Florida Atlantic University Boca Raton, Florida December 2012 Copyright by Kendra L. Philmon 2012 ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This thesis would not have been possible without my thesis advisor Dr. Clifford T. Brown. The idea underlying the project was originally suggested to him by Dr. James Brady, and without this suggestion, we would know nothing about the skeletal remains from Cusirisna Cave. Dr. Brown has provided endless support throughout this process by explaining Mesoamerican archaeology and history, making research and reference suggestions, providing direction, arranging weekly meetings to discuss ideas, offering continuous review and editing, and for instilling confidence in my ability to complete the research. I will be forever grateful to the Department of Anthropology for the opportunity to conduct bioarchaeological research. Thank you to my committee members Drs. Broadfield and Detwiler for their assistance in the research and for reviewing this thesis. Thanks also to Harvard Peabody Museum for their kindness in allowing examination of the Cusirisna Cave collection, for accommodating my research, and especially to Dr. Viva Fisher for approving the radiocarbon sampling and for shipping the specimen, as well as for her support in procuring copies of the documentation and other matters. I also thank Dr. Patricia Kervick who provided access to Earl Flint's reports, and correspondence, made copies of them, and granted us permission to use them. -

Creating an Online Exhibit

CREATING AN ONLINE EXHIBIT: TARANAKI IN THE NEW ZEALAND WARS: 1820-1881 A Project Presented to the faculty of the Department of History California State University, Sacramento Submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in History (Public History) by Tracy Phillips SUMMER 2016 © 2016 Tracy Phillips ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii CREATING AN ONLINE EXHIBIT: TARANAKI IN THE NEW ZEALAND WARS: 1820-1881 A Project by Tracy Phillips Approved by: __________________________________, Committee Chair Patrick Ettinger, PhD __________________________________, Second Reader Christopher Castaneda, PhD ____________________________ Date iii Student: Tracy Phillips I certify that this student has met the requirements for format contained in the University format manual, and that this project is suitable for shelving in the Library and credit is to be awarded for the project. __________________________, Graduate Coordinator ___________________ Patrick Ettinger, PhD Date iv Abstract of CREATING AN ONLINE EXHIBIT: TARANAKI IN THE NEW ZEALAND WARS: 1820-1881 by Tracy Phillips This thesis explicates the impact of land confiscations on Maori-Pakeha relations in Taranaki during the New Zealand Wars and how to convey the narrative in an online exhibit. This paper examines the recent advent of digital humanities and how an online platform requires a different approach to museum practices. It concludes with the planning and execution of the exhibit titled “Taranaki in the New Zealand Wars: 1820- 1881.” _______________________, Committee Chair Patrick Ettinger, PhD _______________________ Date v DEDICATION I would like to dedicate this paper to my son Marlan. He is my inspiration and keeps me motivated to push myself and reach for the stars. -

Oldman Maori.Pdf

[499] Mummification Among the Maoris. Following recent newspaper discussions, Mr. H. D. Skinner sends the following extract from a private letter from Mr. George Graham, 26th July, 1935: “I have myself seen (in situ) human bodies in the urupā (burying-place) in a perfectly preserved condition, in a sitting posture, as originally arranged after death; probably not more than a century or so in age (Kaipara, Arawa, and Kawhia). I am sure mummifying was not a Maori art, the necessary processes would be derogatory from the Maori point of view. “The nearest approach to mummification in New Zealand I ever heard of was connected with the death of Rangitihi (Arawa ancestor of Ngatirangitihi). His body was encased or folded in eight (waru) wrappings (pu), and after some years of retention for wailing over, - 190 at last consigned to the urupā. Hence the pepeha (motto) of that clan: 1. E waru nga pu-manawa a Rangitihi or 2. Rangitihi pu-manawa waru i.e.— 1. Eight were/are the bowel-bindings of Rangitihi. 2. Rangitihi (of the) eight bowel-bindings. “Why Rangitihi was thus provided for after his death is another story—but it seems to have been a historical incident—though unique of its kind. Of course there is another alleged interpretation of the term pumanawa. “The bodies I saw at a cavern urupā at Kaipara (1883 about) were all sitting around the sides of a spacious cavern vault, clothed and bedecked with feather plumes, and the tattooing (all were men) as clear and perfect as can possibly be imagined. -

Olmecs: Where the Sidewalk Begins by Jeffrey Benson Western Oregon University

Olmecs: Where the Sidewalk Begins By Jeffrey Benson Western Oregon University An In Depth Look at the Olmec Controversy Mother Culture or Sister Culture 1 The discovery of the Olmecs has caused archeologists, scientists, historians and scholars from various fields to reevaluate the research of the Olmecs on account of the highly discussed and argued areas of debate that surround the people known as the Olmecs. Given that the Olmecs have only been studied in a more thorough manner for only about a half a century, today we have been able to study this group with more overall gathered information of Mesoamerica and we have been able to take a more technological approach to studying the Olmecs. The studies of the Olmecs reveals much information about who these people were, what kind of a civilization they had, but more importantly the studies reveal a linkage between the Olmecs as a mother culture to later established civilizations including the Mayas, Teotihuacan and other various city- states of Mesoamerica. The data collected links the Olmecs to other cultures in several areas such as writing, pottery and art. With this new found data two main theories have evolved. The first is that the Olmecs were the mother culture. This theory states that writing, the calendar and types of art originated under Olmec rule and later were spread to future generational tribes of Mesoamerica. The second main theory proposes that the Olmecs were one of many contemporary cultures all which acted sister cultures. The thought is that it was not the Olmecs who were the first to introduce writing or the calendar to Mesoamerica but that various indigenous surrounding tribes influenced and helped establish forms of writing, a calendar system and common types of art. -

The Prehistoric Use of Nephrite on the British Columbia Plateau

The Prehistoric Use of Nephrite on the British Columbia Plateau John Darwent Archaeology Press Simon Fraser University 1998 The Prehistoric Use of Nephrite on the British Columbia Plateau By John Darwent Archaeology Press Simon Fraser University 1998 c. Archaeology Press 1998 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form, without prior written consent of the publisher. Printed and bound in Canada ISBN 0-86491-189-0 Publication No. 25 Archaeology Press Department of Archaeology Simon Fraser University Burnaby, B.C. V5A 1S6 (604)291-3135 Fax: (604) 291-5666 Editor: Roy L. Carlson Cover: Nephrite celts from near Lillooet, B.C. SFU Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology Cat nos. 2750 and 2748 Table of Contents Acknowledgments v List of Tables vi List of Figures vii Chapter 1 Introduction 1 Types of Data 2 Ethnographic Information 2 Experimental Reconstruction 2 Context and Distribution 3 Artifact Observations 3 Analog Information 4 The Study Area . 4 Report Organization 4 2 Nephrite 6 Chemical and Physical Properties of Nephrite 6 Sources in the Pacific Northwest 6 Nephrite Sources in British Columbia 6 The Lillooet Segment 7 Omineca Segment 7 Cassiar Segment 7 Yukon and Alaska Nephrite Sources 8 Washington State and Oregon Nephrite Sources 8 Wyoming Nephrite Sources 9 Prehistoric Source Usage 9 Alternate Materials to Nephrite 10 Serpentine 10 Greenstone 10 Jadeite 10 Vesuvianite 10 3 Ethnographic and Archaeological Background of Nephrite Use 11 Ethnolinguistic Groups in the Study Area 11 Plateau Lifestyle 11 Cultural Complexity on the Plateau 11 Ethnographic Use of Nephrite .