UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO Maya Jade T-Shape

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Treatise on Combined Metalworking Techniques: Forged Elements and Chased Raised Shapes Bonnie Gallagher

Rochester Institute of Technology RIT Scholar Works Theses Thesis/Dissertation Collections 1972 Treatise on combined metalworking techniques: forged elements and chased raised shapes Bonnie Gallagher Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.rit.edu/theses Recommended Citation Gallagher, Bonnie, "Treatise on combined metalworking techniques: forged elements and chased raised shapes" (1972). Thesis. Rochester Institute of Technology. Accessed from This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Thesis/Dissertation Collections at RIT Scholar Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses by an authorized administrator of RIT Scholar Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TREATISE ON COMBINED METALWORKING TECHNIQUES i FORGED ELEMENTS AND CHASED RAISED SHAPES TREATISE ON. COMBINED METALWORKING TECHNIQUES t FORGED ELEMENTS AND CHASED RAISED SHAPES BONNIE JEANNE GALLAGHER CANDIDATE FOR THE MASTER OF FINE ARTS IN THE COLLEGE OF FINE AND APPLIED ARTS OF THE ROCHESTER INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY AUGUST ( 1972 ADVISOR: HANS CHRISTENSEN t " ^ <bV DEDICATION FORM MUST GIVE FORTH THE SPIRIT FORM IS THE MANNER IN WHICH THE SPIRIT IS EXPRESSED ELIEL SAARINAN IN MEMORY OF MY FATHER, WHO LONGED FOR HIS CHILDREN TO HAVE THE OPPORTUNITY TO HAVE THE EDUCATION HE NEVER HAD THE FORTUNE TO OBTAIN. vi PREFACE Although the processes of raising, forging, and chasing of metal have been covered in most technical books, to date there is no major source which deals with the functional and aesthetic requirements -

Tik 02:Tik 02

2 The Ceramics of Tikal T. Patrick Culbert More than 40 years of archaeological research at Tikal have pro- duced an enormous quantity of ceramics that have been studied by a variety of investigators (Coggins 1975; Culbert 1963, 1973, 1977, 1979, 1993; Fry 1969, 1979; Fry and Cox 1974; Hermes 1984a; Iglesias 1987, 1988; Laporte and Fialko 1987, 1993; Laporte et al. 1992; Laporte and Iglesias 1992; Laporte, this volume). It could be argued that the ceram- ics of Tikal are better known than those from any other Maya site. The contexts represented by the ceramic collections are extremely varied, as are the formation processes to which they were subjected both in Maya times and since the site was abandoned. This chapter will report primarily on the ceramics recovered by the University of Pennsylvania Tikal Project between 1956 and 1970. The information available from this analysis has been significantly clar- ified and expanded by later research, especially that of the Proyecto Nacional Tikal (Hermes 1984a; Iglesias 1987, 1988; Laporte and Fialko 1987, 1993; Laporte et al. 1992; Laporte and Iglesias 1992; Laporte, this volume). I will make reference to some of the results of these later stud- ies but will not attempt an overall synthesis—something that must await Copyrighted Material www.sarpress.org 47 T. PATRICK C ULBERT a full-scale conference involving all of those who have worked with Tikal ceramics. Primary goals of my analysis of Tikal ceramics were to develop a ceramic sequence and to provide chronological information for researchers. Although a ceramic sequence was already available from the neighboring site of Uaxactun (R. -

Castingmetal

CASTING METAL Sophistication from the surprisingly simple with a room casting. Hmmmm. I I asked Beth where in the world she BROOM pored through every new and learned how to cast metal using the Bvintage metals technique book Brad Smith offers a Broom business end of a broom. “It’s an old BY HELEN I. DRIGGS on my shelf and I couldn’t find a men- Casting Primer, page 32, hobbyist trick. I learned about it from a tion of the process anywhere. This and a project for using very talented guy named Stu Chalfant the elements you cast. transformed my curiosity into an who gave a demo for my rock group TRYBROOM-CAST IT YOURSELFE urgent and obsessive quest. I am an G — the Culver City [California] Rock & A TURQUOISE PENDANT P information junkie — especially Mineral Club. This was six or seven when it comes to studio jewelry — years ago, and I instantly fell in love and I love finding out new, old fash- with the organic, yet orderly shapes.” ioned ways of doing things. But, I am also efficient. So I A few years passed before Beth tried the technique her- knew the best way to proceed was to seek out Beth self. “The first of our club members to experiment with it Rosengard, who has transformed this delightfully low-tech was Brad 34Smith, who now includes the technique in the approach to molten metal into a sophisticated level of artis- classes he teaches at the Venice Adult School.” After admir- tic expression. I had made a mental note to investigate ing some early silver castings Brad had made, she begged broom casting when I saw her winning earrings in the 2006 him for a sample and later incorporated his work into her Jewelry Arts Awards. -

Lapidary Journal Jewelry Artist March 2012

INDEX TO VOLUME 65 Lapidary Journal Jewelry Artist April 2011-March 2012 INDEX BY FEATURE/ Signature Techniques Part 1 Resin Earrings and Pendant, PROJECT/DEPARTMENT of 2, 20, 09/10-11 30, 08-11 Signature Techniques Part 2 Sagenite Intarsia Pendant, 50, With title, page number, of 2, 18, 11-11 04-11 month, and year published Special Event Sales, 22, 08-11 Silver Clay and Wire Ring, 58, When to Saw Your Rough, 74, 03-12 FEATURE ARTICLES Smokin’*, 43, 09/10-11 01/02-12 Argentium® Tips, 50, 03-12 Spinwheel, 20, 08-11 Arizona Opal, 22, 01/02-12 PROJECTS/DEMOS/FACET Stacking Ring Trio, 74, Basic Files, 36, 11-11 05/06-11 DESIGNS Brachiopod Agate, 26, 04-11 Sterling Safety Pin, 22, 12-11 Alabaster Bowls, 54, 07-11 Create Your Best Workspace, Swirl Step Cut Revisited, 72, Amethyst Crystal Cross, 34, 28, 11-11 01/02-12 Cut Together, 66, 01/02-12 12-11 Tabbed Fossil Coral Pendant, Deciphering Chinese Writing Copper and Silver Clay 50, 01/02-12 Linked Bracelet, 48, 07-11 12, 07-11 Stone, 78, 01/02-12 Torch Fired Enamel Medallion Site of Your Own, A, 12, 03-12 Easier Torchwork, 43, 11-11 Copper Wire Cuff with Silver Necklace, 33, 09/10-11 Elizabeth Taylor’s Legendary Wire “Inlay,” 28, 07-11 Trillion Diamonds Barion, 44, SMOKIN’ STONES Jewels, 58, 12-11 Coquina Pendant, 44, 05/06-11 Alabaster, 52, 07-11 Ethiopian Opal, 28, 01/02-12 01/02-12 Turquoise and Pierced Silver Ametrine, 44, 09/10-11 Find the Right Findings, 46, Corrugated Copper Pendant, Bead Bracelet – Plus!, 44, Coquina, 42, 01/02-12 09/10-11 24, 05/06-11 04-11 Fossilized Ivory, 24, 04-11 -

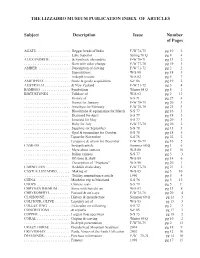

List of Articles

THE LIZZADRO MUSEUM PUBLICATION INDEX OF ARTICLES Subject Description Issue Number of Pages AGATE. .. Beggar beads of India F-W 74-75 pg 10 2 . Lake Superior Spring 70 Q pg 8 4 ALEXANDRITE . & Synthetic alexandrite F-W 70-71 pg 13 2 . Gem with color change F-W 77-78 pg 19 1 AMBER . Description of carving F-W 71-72 pg 2 2 . Superstitions W-S 80 pg 18 5 . in depth treatise W-S 82 pg 5 7 AMETHYST . Stone & geode acquisitions S-F 86 pg 19 2 AUSTRALIA . & New Zealand F-W 71-72 pg 3 4 BAMBOO . Symbolism Winter 68 Q pg 8 1 BIRTHSTONES . Folklore of W-S 93 pg 2 13 . History of S-S 71 pg 27 4 . Garnet for January F-W 78-79 pg 20 3 . Amethyst for February F-W 78-79 pg 22 3 . Bloodstone & aquamarine for March S-S 77 pg 16 3 . Diamond for April S-S 77 pg 18 3 . Emerald for May S-S 77 pg 20 3 . Ruby for July F-W 77-78 pg 20 2 . Sapphire for September S-S 78 pg 15 3 . Opal & tourmaline for October S-S 78 pg 18 5 . Topaz for November S-S 78 pg 22 2 . Turquoise & zircon for December F-W 78-79 pg 16 5 CAMEOS . In-depth article Summer 68 Q pg 1 6 . More about cameos W-S 80 pg 5 10 . Italian cameos S-S 77 pg 3 3 . Of stone & shell W-S 89 pg 14 6 . Description of “Neptune” W-S 90 pg 20 1 CARNELIAN . -

Historical Painting Techniques, Materials, and Studio Practice

Historical Painting Techniques, Materials, and Studio Practice PUBLICATIONS COORDINATION: Dinah Berland EDITING & PRODUCTION COORDINATION: Corinne Lightweaver EDITORIAL CONSULTATION: Jo Hill COVER DESIGN: Jackie Gallagher-Lange PRODUCTION & PRINTING: Allen Press, Inc., Lawrence, Kansas SYMPOSIUM ORGANIZERS: Erma Hermens, Art History Institute of the University of Leiden Marja Peek, Central Research Laboratory for Objects of Art and Science, Amsterdam © 1995 by The J. Paul Getty Trust All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America ISBN 0-89236-322-3 The Getty Conservation Institute is committed to the preservation of cultural heritage worldwide. The Institute seeks to advance scientiRc knowledge and professional practice and to raise public awareness of conservation. Through research, training, documentation, exchange of information, and ReId projects, the Institute addresses issues related to the conservation of museum objects and archival collections, archaeological monuments and sites, and historic bUildings and cities. The Institute is an operating program of the J. Paul Getty Trust. COVER ILLUSTRATION Gherardo Cibo, "Colchico," folio 17r of Herbarium, ca. 1570. Courtesy of the British Library. FRONTISPIECE Detail from Jan Baptiste Collaert, Color Olivi, 1566-1628. After Johannes Stradanus. Courtesy of the Rijksmuseum-Stichting, Amsterdam. Library of Congress Cataloguing-in-Publication Data Historical painting techniques, materials, and studio practice : preprints of a symposium [held at] University of Leiden, the Netherlands, 26-29 June 1995/ edited by Arie Wallert, Erma Hermens, and Marja Peek. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 0-89236-322-3 (pbk.) 1. Painting-Techniques-Congresses. 2. Artists' materials- -Congresses. 3. Polychromy-Congresses. I. Wallert, Arie, 1950- II. Hermens, Erma, 1958- . III. Peek, Marja, 1961- ND1500.H57 1995 751' .09-dc20 95-9805 CIP Second printing 1996 iv Contents vii Foreword viii Preface 1 Leslie A. -

A Mat of Serpents: Aztec Strategies of Control from an Empire in Decline

A Mat of Serpents: Aztec Strategies of Control from an Empire in Decline Jerónimo Reyes On my honor, Professors Andrea Lepage and Elliot King mark the only aid to this thesis. “… the ruler sits on the serpent mat, and the crown and the skull in front of him indicate… that if he maintained his place on the mat, the reward was rulership, and if he lost control, the result was death.” - Aztec rulership metaphor1 1 Emily Umberger, " The Metaphorical Underpinnings of Aztec History: The Case of the 1473 Civil War," Ancient Mesoamerica 18, 1 (2007): 18. I dedicate this thesis to my mom, my sister, and my brother for teaching me what family is, to Professor Andrea Lepage for helping me learn about my people, to Professors George Bent, and Melissa Kerin for giving me the words necessary to find my voice, and to everyone and anyone finding their identity within the self and the other. Table of Contents List of Illustrations ………………………………………………………………… page 5 Introduction: Threads Become Tapestry ………………………………………… page 6 Chapter I: The Sum of its Parts ………………………………………………… page 15 Chapter II: Commodification ………………………………………………… page 25 Commodification of History ………………………………………… page 28 Commodification of Religion ………………………………………… page 34 Commodification of the People ………………………………………… page 44 Conclusion ……………………………………………………………………... page 53 Illustrations ……………………………………………………………………... page 54 Appendices ……………………………………………………………………... page 58 Bibliography ……………………………………………………………………... page 60 …. List of Illustrations Figure 1: Statue of Coatlicue, Late Period, 1439 (disputed) Figure 2: Peasant Ritual Figurines, Date Unknown Figure 3: Tula Warrior Figure Figure 4: Mexica copy of Tula Warrior Figure, Late Aztec Period Figure 5: Coyolxauhqui Stone, Late Aztec Period, 1473 Figure 6: Male Coyolxauhqui, carving on greenstone pendant, found in cache beneath the Coyolxauhqui Stone, Date Unknown Figure 7: Vessel with Tezcatlipoca Relief, Late Aztec Period, ca. -

Download Article

ThePARIJournal A quarterly publication of the Ancient Cultures Institute Volume XIX, No. 2, Fall 2018 A Preliminary Analysis of Altar 5 In This Issue: from La Corona A Preliminary David Stuart Analysis of Altar 5 Marcello Canuto from La Corona Tomás Barrientos by Alejandro González David Stuart Marcello Canuto Tomás Barrientos Excavations during the 2017 and 2018 field even pristine condition, with remains of and Alejandro seasons at La Corona, Guatemala, revealed red paint. As the inscription makes clear, González a limestone relief sculpture bearing the the altar is a monument commemorating portrait of a seated lord with an accompa- Chak Tok Ich’aak’s participation in a PAGES 1-13 nying hieroglyphic text (Figure 1). It was calendar ritual in the year 544 CE, on the • discovered set into the floor of an early occasion of a k’atun’s half-period. Here we In Memoriam: platform in front of the architectural com- will discuss some important details about Alfonso Lacadena plex known as the Coronitas group, one of this ruler and his connection to the wider García-Gallo La Corona’s most important architectural political world of the Maya lowlands in complexes. We call this new monument the sixth century. by Altar 5 in the designation system of La Marc Zender Corona’s sculpture (see Stuart et al. 2015). Archaeological Context PAGES 14-20 The monument bears an inscribed Long Count date of 9.5.10.0.0, firmly placing it Altar 5 was discovered during investiga- in the year 544 CE, making it the earliest tions into a small structure, Str. -

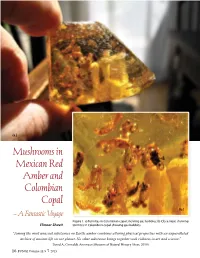

“Among the Most Unusual Substances on Earth, Amber Combines Alluring Physical Properties with an Unparalleled Archive of Ancient Life on Our Planet

(a.) (b.) Figure 1. a) Termites in Colombian copal showing gas bubbles; b) Close view, showing termites in Colombian copal showing gas bubbles. “Among the most unusual substances on Earth, amber combines alluring physical properties with an unparalleled archive of ancient life on our planet. No other substance brings together such richness in art and science.” David A. Grimaldi, American Museum of Natural History (Ross, 2010) 16 FUNGI Volume 11:5 2019 Figure 2. A rough piece of blue Dominican amber. y quest for mushrooms in Mushroom lovers were treated to a and so versatile. As a gemologist, amber amber and copal lasted about small, extremely rare piece of light- was an organic, semi-precious gemstone a decade, from the mid-1990s colored amber, inside which a tiny gilled for me, soft for a gemstone (only 2-2.5 Mto the early part of the 2000s. During mushroom was barely visible. Through on the Mohs scale), and with multiple this period of time, I found mushrooms a strategically placed magnifying glass, places of origin around the world. It in Mexican red amber from Chiapas, excited visitors could get a glimpse of came in multiple colors, and lended itself and in Colombian copal from the what the ancestor of today’s Mycena to carving and the creation of beautiful Santander region; these pieces make up looked like, down to its cap, delicate works of art. As a mycologist seeking the bulk of my collection. The unique gills, and stipe. Though an extinct mushrooms inside the amber, amber fossils of mushrooms, amber, and copal species and millions of years old, the was the fully polymerized tree resin that in this collection are still waiting to be fossilized mushroom looked fresh and formed millions of years ago in what studied. -

The PARI Journal Vol. XII, No. 3

ThePARIJournal A quarterly publication of the Pre-Columbian Art Research Institute Volume XII, No. 3, Winter 2012 Excavations of Nakum Structure 15: Discoveryof Royal Burials and In This Issue: Accompanying Offerings JAROSŁAW ŹRAŁKA Excavations of Institute of Archaeology, Jagiellonian University NakumStructure15: WIESŁAW KOSZKUL Discovery of Institute of Archaeology, Jagiellonian University Royal Burials and BERNARD HERMES Accompanying Proyecto Arqueológico Nakum, Guatemala Offerings SIMON MARTIN by University of Pennsylvania Museum Jarosław Źrałka Introduction the Triangulo Project of the Guatemalan Wiesław Koszkul Institute of Anthropology and History Bernard Hermes Two royal burials along with many at- (IDAEH). As a result of this research, the and tendant offerings were recently found epicenter and periphery of the site have Simon Martin in a pyramid located in the Acropolis been studied in detail and many structures complex at the Maya site of Nakum. These excavated and subsequently restored PAGES 1-20 discoveries were made during research (Calderón et al. 2008; Hermes et al. 2005; conducted under the aegis of the Nakum Hermes and Źrałka 2008). In 2006, thanks Archaeological Project, which has been to permission granted from IDAEH, a excavating the site since 2006. Artefacts new archaeological project was started Joel Skidmore discovered in the burials and the pyramid Editor at Nakum (The Nakum Archaeological [email protected] significantly enrich our understanding of Project) directed by Wiesław Koszkul the history of Nakum and throw new light and Jarosław Źrałka from the Jagiellonian Marc Zender on its relationship with neighboring sites. University, Cracow, Poland. Recently our Associate Editor Nakum is one of the most important excavations have focused on investigating [email protected] Maya sites located in the northeastern two untouched pyramids located in the Peten, Guatemala, in the area of the Southern Sector of the site, in the area of The PARI Journal Triangulo Park (a “cultural triangle” com- the so-called Acropolis. -

The Bilimek Pulque Vessel (From in His Argument for the Tentative Date of 1 Ozomatli, Seler (1902-1923:2:923) Called Atten- Nicholson and Quiñones Keber 1983:No

CHAPTER 9 The BilimekPulqueVessel:Starlore, Calendrics,andCosmologyof LatePostclassicCentralMexico The Bilimek Vessel of the Museum für Völkerkunde in Vienna is a tour de force of Aztec lapidary art (Figure 1). Carved in dark-green phyllite, the vessel is covered with complex iconographic scenes. Eduard Seler (1902, 1902-1923:2:913-952) was the first to interpret its a function and iconographic significance, noting that the imagery concerns the beverage pulque, or octli, the fermented juice of the maguey. In his pioneering analysis, Seler discussed many of the more esoteric aspects of the cult of pulque in ancient highland Mexico. In this study, I address the significance of pulque in Aztec mythology, cosmology, and calendrics and note that the Bilimek Vessel is a powerful period-ending statement pertaining to star gods of the night sky, cosmic battle, and the completion of the Aztec 52-year cycle. The Iconography of the Bilimek Vessel The most prominent element on the Bilimek Vessel is the large head projecting from the side of the vase (Figure 2a). Noting the bone jaw and fringe of malinalli grass hair, Seler (1902-1923:2:916) suggested that the head represents the day sign Malinalli, which for the b Aztec frequently appears as a skeletal head with malinalli hair (Figure 2b). However, because the head is not accompanied by the numeral coefficient required for a completetonalpohualli Figure 2. Comparison of face date, Seler rejected the Malinalli identification. Based on the appearance of the date 8 Flint on front of Bilimek Vessel with Aztec Malinalli sign: (a) face on on the vessel rim, Seler suggested that the face is the day sign Ozomatli, with an inferred Bilimek Vessel, note malinalli tonalpohualli reference to the trecena 1 Ozomatli (1902-1923:2:922-923). -

Imitation Amber Beads of Phenolic Resin from the African Trade

IMITATION AMBER BEADS OF PHENOLIC RESIN FROM THE AFRICAN TRADE Rosanna Falabella Examination of contemporary beads with African provenance reveals large quantities of imitation amber beads made of phenol- formaldehyde thermosetting resins (PFs). This article delves into the early industrial history of PFs and their use in the production of imitation amber and bead materials. Attempts to discover actual sources that manufactured imitation amber beads for export to Africa and the time frame have not been very fruitful. While evidence exists that PFs were widely used as amber substitutes within Europe, only a few post-WWII references explicitly report the export of imitation amber PF beads to Africa. However they arrived in Africa, the durability of PF beads gave African beadworkers aesthetic freedom not only to rework the original beads into a variety of shapes and sizes, and impart decorative elements, but also to apply heat treatment to modify colors. Some relatively simple tests to distinguish PFs from other bead materials are presented. Figure 1. Beads of phenol-formaldehyde thermosetting resins INTRODUCTION (PFs) from the African trade. The large bead at bottom center is 52.9 mm in diameter (metric scale) (all images by the author unless otherwise noted). Strands of machined and polished amber-yellow beads, from small to very large (Figure 1), are found today in the He reports that other shapes, such as barrel and spherical stalls of many African bead sellers as well as in on-line (Figure 2), were imported as well, but the short oblates stores and auction sites. They are usually called “African are the most common.