Quick Practice Guides Index with Few Exceptions, the Quick Practice Guides in PCF Are Restricted to a Maximum of 2 Pages in Order to Facilitate Everyday Use

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Classification of Medicinal Drugs and Driving: Co-Ordination and Synthesis Report

Project No. TREN-05-FP6TR-S07.61320-518404-DRUID DRUID Driving under the Influence of Drugs, Alcohol and Medicines Integrated Project 1.6. Sustainable Development, Global Change and Ecosystem 1.6.2: Sustainable Surface Transport 6th Framework Programme Deliverable 4.4.1 Classification of medicinal drugs and driving: Co-ordination and synthesis report. Due date of deliverable: 21.07.2011 Actual submission date: 21.07.2011 Revision date: 21.07.2011 Start date of project: 15.10.2006 Duration: 48 months Organisation name of lead contractor for this deliverable: UVA Revision 0.0 Project co-funded by the European Commission within the Sixth Framework Programme (2002-2006) Dissemination Level PU Public PP Restricted to other programme participants (including the Commission x Services) RE Restricted to a group specified by the consortium (including the Commission Services) CO Confidential, only for members of the consortium (including the Commission Services) DRUID 6th Framework Programme Deliverable D.4.4.1 Classification of medicinal drugs and driving: Co-ordination and synthesis report. Page 1 of 243 Classification of medicinal drugs and driving: Co-ordination and synthesis report. Authors Trinidad Gómez-Talegón, Inmaculada Fierro, M. Carmen Del Río, F. Javier Álvarez (UVa, University of Valladolid, Spain) Partners - Silvia Ravera, Susana Monteiro, Han de Gier (RUGPha, University of Groningen, the Netherlands) - Gertrude Van der Linden, Sara-Ann Legrand, Kristof Pil, Alain Verstraete (UGent, Ghent University, Belgium) - Michel Mallaret, Charles Mercier-Guyon, Isabelle Mercier-Guyon (UGren, University of Grenoble, Centre Regional de Pharmacovigilance, France) - Katerina Touliou (CERT-HIT, Centre for Research and Technology Hellas, Greece) - Michael Hei βing (BASt, Bundesanstalt für Straßenwesen, Germany). -

Hyperinflation Management Medications Requiring Prior Authorization for Medical Necessity

July 2021 Effective 07/01/2021 Hyperinflation Management Medications Requiring Prior Authorization for Medical Necessity Below is a list of medicines by drug class that will not be covered without a prior authorization for medical necessity. If you continue using one of these drugs without prior approval for medical necessity, you may be required to pay the full cost. If you are currently using one of the drugs requiring prior authorization for medical necessity, ask your d octor to choose one of the generic or brand formulary options listed below. Category * Drugs Requiring Prior Formulary Options Drug Class Authorization for Medical Necessity 1 Allergies Dexchlorpheniramine levocetirizine Antihistamines Diphen Elixir (NDC^ 69067009204 only) RyClora CARBINOXAMINE TABLET 6 MG Anti-convulsants topiramate ext-rel capsule carbamazepine, carbamazepine ext-rel, (generics for QUDEXY XR only) clobazam, divalproex sodium, divalproex sodium ext-rel, gabapentin, lamotrigine, lamotrigine ext-rel, levetiracetam, levetiracetam ext-rel, oxcarbazepine, phenobarbital, phenytoin, phenytoin sodium extended, primidone, rufinamide, tiagabine, topiramate, valproic acid, zonisamide, FYCOMPA, OXTELLAR XR, TROKENDI XR, VIMPAT, XCOPRI ZONEGRAN carbamazepine, carbamazepine ext-rel, divalproex sodium, divalproex sodium ext-rel, gabapentin, lamotrigine, lamotrigine ext-rel, levetiracetam, levetiracetam ext-rel, oxcarbazepine, phenobarbital, phenytoin, phenytoin sodium extended, primidone, tiagabine, topiramate, valproic acid, zonisamide, FYCOMPA, OXTELLAR XR, TROKENDI -

Medicines Used Across Wirral Health Economy

Medicines used across Wirral Health Economy Below is a list of medicines that are approved for use on Wirral. Some medicines may only be prescribed in hospital, others may be prescribed by your GP. The list is updated every time a new medicine is approved for use in Wirral. Some medicines have been recommended by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). The middle column of the table below indicates recommendations made by NICE — eg, TA234 means that the medicine was reviewed in NICE technology appraisal number 234. Some of the medicines we use are recommended by specialists working from the Walton Centre NHS Foundation Trust or from the Cheshire and Wirral Partnership NHS Foundation Trust. These medicines are included in our formulary — however; the prescriber retains responsibility for the appropriate use of these medicines. These formularies are obtainable here: http://www.panmerseyapc.nhs.uk/formulary/documents/04- 0800_antiepileptic_drugs.pdf http://www.panmerseyapc.nhs.uk/formulary/documents/04-09- 00_parkinsonism.pdf http://www.cwp.nhs.uk/pages/629-pharmacy-and-medicines-information Subject to NICE Drug Name recommendation Abatacept TA195, TA280 Acamprosate Acarbose Accu-Chek Inform II® AccuSol® 35 Potassium 4mmol/L Acetazolamide Acetylcysteine Acencoumarol Acetic acid 5% solution Acetone Acitretin Aciclovir Wirral Medicines Formulary Author: Medicines Management Team Approved by: Wirral Drug and Therapeutics Panel Last updated: June 2015 Version 10 Aclinidium Actilite® Activated Charcoal Activon® - see -

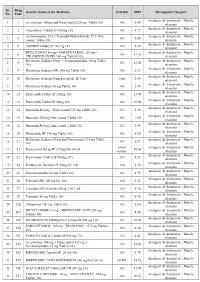

PMBJP Product.Pdf

Sr. Drug Generic Name of the Medicine Unit Size MRP Therapeutic Category No. Code Analgesic & Antipyretic / Muscle 1 1 Aceclofenac 100mg and Paracetamol 325 mg Tablet 10's 10's 8.00 relaxants Analgesic & Antipyretic / Muscle 2 2 Aceclofenac Tablets IP 100mg 10's 10's 4.37 relaxants Acetaminophen 325 + Tramadol Hydrochloride 37.5 film Analgesic & Antipyretic / Muscle 3 4 10's 8.00 coated Tablet 10's relaxants Analgesic & Antipyretic / Muscle 4 5 ASPIRIN Tablets IP 150 mg 14's 14's 2.70 relaxants DICLOFENAC 50 mg+ PARACETAMOL 325 mg+ Analgesic & Antipyretic / Muscle 5 6 10's 11.30 CHLORZOXAZONE 500 mg Tablets 10's relaxants Diclofenac Sodium 50mg + Serratiopeptidase 10mg Tablet Analgesic & Antipyretic / Muscle 6 8 10's 12.00 10's relaxants Analgesic & Antipyretic / Muscle 7 9 Diclofenac Sodium (SR) 100 mg Tablet 10's 10's 6.12 relaxants Analgesic & Antipyretic / Muscle 8 10 Diclofenac Sodium 25mg per ml Inj. IP 3 ml 3 ml 2.00 relaxants Analgesic & Antipyretic / Muscle 9 11 Diclofenac Sodium 50 mg Tablet 10's 10's 2.90 relaxants Analgesic & Antipyretic / Muscle 10 12 Etoricoxilb Tablets IP 120mg 10's 10's 33.00 relaxants Analgesic & Antipyretic / Muscle 11 13 Etoricoxilb Tablets IP 90mg 10's 10's 25.00 relaxants Analgesic & Antipyretic / Muscle 12 14 Ibuprofen 400 mg + Paracetamol 325 mg Tablet 10's 15's 5.50 relaxants Analgesic & Antipyretic / Muscle 13 15 Ibuprofen 200 mg film coated Tablet 10's 10's 1.80 relaxants Analgesic & Antipyretic / Muscle 14 16 Ibuprofen 400 mg film coated Tablet 10's 15's 3.50 relaxants Analgesic & Antipyretic -

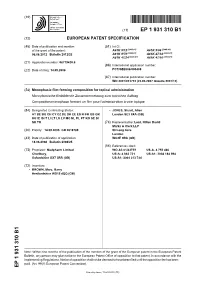

Ep 1931310 B1

(19) & (11) EP 1 931 310 B1 (12) EUROPEAN PATENT SPECIFICATION (45) Date of publication and mention (51) Int Cl.: of the grant of the patent: A61K 9/12 (2006.01) A61K 9/06 (2006.01) 06.06.2012 Bulletin 2012/23 A61K 9/70 (2006.01) A61K 47/32 (2006.01) A61K 47/24 (2006.01) A61K 47/10 (2006.01) (21) Application number: 06779420.6 (86) International application number: (22) Date of filing: 14.09.2006 PCT/GB2006/003408 (87) International publication number: WO 2007/031753 (22.03.2007 Gazette 2007/12) (54) Monophasic film-forming composition for topical administration Monophasische filmbildende Zusammensetzung zum topischen Auftrag Composition monophase formant un film pour l’administration à voie topique (84) Designated Contracting States: • JONES, Stuart, Allen AT BE BG CH CY CZ DE DK EE ES FI FR GB GR London SE3 0XA (GB) HU IE IS IT LI LT LU LV MC NL PL PT RO SE SI SK TR (74) Representative: Lord, Hilton David Marks & Clerk LLP (30) Priority: 14.09.2005 GB 0518769 90 Long Acre London (43) Date of publication of application: WC2E 9RA (GB) 18.06.2008 Bulletin 2008/25 (56) References cited: (73) Proprietor: Medpharm Limited WO-A2-01/43722 US-A- 4 752 466 Charlbury, US-A- 4 863 721 US-A1- 2004 184 994 Oxfordshire OX7 3RR (GB) US-A1- 2004 213 744 (72) Inventors: • BROWN, Marc, Barry Hertfordshire WD19 4QQ (GB) Note: Within nine months of the publication of the mention of the grant of the European patent in the European Patent Bulletin, any person may give notice to the European Patent Office of opposition to that patent, in accordance with the Implementing Regulations. -

Meta-Xylene: Identification of a New Antigenic Entity in Hypersensitivity

Clinical Communications Meta-xylene: identification of a new Our patient is a 53-year-old male who presented in 2003 with antigenic entity in hypersensitivity contact dermatitis after the use of lidocaine and disinfection with reactions to local anesthetics chlorhexidine. In 2006, an extensive skin testing by patch, prick, Kuntheavy Ing Lorenzini, PhDa, intradermal sampling, and graded challenge was performed as b c followed. The patch tests were performed with the thin layer Fabienne Gay-Crosier Chabry, MD , Claude Piguet, PhD , rapid use epicutaneous test, using the caine mix (benzocaine, a and Jules Desmeules, MD tetracaine, and cinchocaine), the paraben mix (methyl, ethyl, propyl, butyl, and benzylparaben), and the Balsam of Peru. The Clinical Implications caine and paraben mix were positive, and the patch test was possibly positive for Balsam of Peru. The prick test performed The authors report a patient who presented delayed with preservative-free lidocaine 20 mg/mL (Lidocaïne HCl hypersensitivity reactions to several local anesthetics, all “Bichsel” 2%, Grosse Apotheke Dr. G. Bichsel, Switzerland) was containing a meta-xylene entity, but not to articaine, negative. The intradermal test, performed with lidocaine 20 mg/ which is a thiophene derivative. Meta-xylene could be the mL containing methylparaben (Xylocain 2%, AstraZeneca, immunogenic epitope. Switzerland) with 1/10 and 1/100 dilutions, was negative. The subcutaneous challenge test was performed with 10 mg of preservative-free lidocaine 20 mg/mL (Lidocaïne HCl “Bichsel” TO THE EDITOR: 2%, Grosse Apotheke Dr. G. Bichsel) and lidocaine 20 mg/mL containing methylparaben (Lidocaïne Streuli 2%, Streuli, Hypersensitivity reactions to local anesthetics (LAs) are rare and Switzerland), both of which were positive and had the appear- represent less than 1% of all adverse reactions to LAs. -

1: Gastro-Intestinal System

1 1: GASTRO-INTESTINAL SYSTEM Antacids .......................................................... 1 Stimulant laxatives ...................................46 Compound alginate products .................. 3 Docuate sodium .......................................49 Simeticone ................................................... 4 Lactulose ....................................................50 Antimuscarinics .......................................... 5 Macrogols (polyethylene glycols) ..........51 Glycopyrronium .......................................13 Magnesium salts ........................................53 Hyoscine butylbromide ...........................16 Rectal products for constipation ..........55 Hyoscine hydrobromide .........................19 Products for haemorrhoids .................56 Propantheline ............................................21 Pancreatin ...................................................58 Orphenadrine ...........................................23 Prokinetics ..................................................24 Quick Clinical Guides: H2-receptor antagonists .......................27 Death rattle (noisy rattling breathing) 12 Proton pump inhibitors ........................30 Opioid-induced constipation .................42 Loperamide ................................................35 Bowel management in paraplegia Laxatives ......................................................38 and tetraplegia .....................................44 Ispaghula (Psyllium husk) ........................45 ANTACIDS Indications: -

Local Anesthetics

Local Anesthetics Introduction and History Cocaine is a naturally occurring compound indigenous to the Andes Mountains, West Indies, and Java. It was the first anesthetic to be discovered and is the only naturally occurring local anesthetic; all others are synthetically derived. Cocaine was introduced into Europe in the 1800s following its isolation from coca beans. Sigmund Freud, the noted Austrian psychoanalyst, used cocaine on his patients and became addicted through self-experimentation. In the latter half of the 1800s, interest in the drug became widespread, and many of cocaine's pharmacologic actions and adverse effects were elucidated during this time. In the 1880s, Koller introduced cocaine to the field of ophthalmology, and Hall introduced it to dentistry Overwiev Local anesthetics (LAs) are drugs that block the sensation of pain in the region where they are administered. LAs act by reversibly blocking the sodium channels of nerve fibers, thereby inhibiting the conduction of nerve impulses. Nerve fibers which carry pain sensation have the smallest diameter and are the first to be blocked by LAs. Loss of motor function and sensation of touch and pressure follow, depending on the duration of action and dose of the LA used. LAs can be infiltrated into skin/subcutaneous tissues to achieve local anesthesia or into the epidural/subarachnoid space to achieve regional anesthesia (e.g., spinal anesthesia, epidural anesthesia, etc.). Some LAs (lidocaine, prilocaine, tetracaine) are effective on topical application and are used before minor invasive procedures (venipuncture, bladder catheterization, endoscopy/laryngoscopy). LAs are divided into two groups based on their chemical structure. The amide group (lidocaine, prilocaine, mepivacaine, etc.) is safer and, hence, more commonly used in clinical practice. -

![Ehealth DSI [Ehdsi V2.2.2-OR] Ehealth DSI – Master Value Set](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8870/ehealth-dsi-ehdsi-v2-2-2-or-ehealth-dsi-master-value-set-1028870.webp)

Ehealth DSI [Ehdsi V2.2.2-OR] Ehealth DSI – Master Value Set

MTC eHealth DSI [eHDSI v2.2.2-OR] eHealth DSI – Master Value Set Catalogue Responsible : eHDSI Solution Provider PublishDate : Wed Nov 08 16:16:10 CET 2017 © eHealth DSI eHDSI Solution Provider v2.2.2-OR Wed Nov 08 16:16:10 CET 2017 Page 1 of 490 MTC Table of Contents epSOSActiveIngredient 4 epSOSAdministrativeGender 148 epSOSAdverseEventType 149 epSOSAllergenNoDrugs 150 epSOSBloodGroup 155 epSOSBloodPressure 156 epSOSCodeNoMedication 157 epSOSCodeProb 158 epSOSConfidentiality 159 epSOSCountry 160 epSOSDisplayLabel 167 epSOSDocumentCode 170 epSOSDoseForm 171 epSOSHealthcareProfessionalRoles 184 epSOSIllnessesandDisorders 186 epSOSLanguage 448 epSOSMedicalDevices 458 epSOSNullFavor 461 epSOSPackage 462 © eHealth DSI eHDSI Solution Provider v2.2.2-OR Wed Nov 08 16:16:10 CET 2017 Page 2 of 490 MTC epSOSPersonalRelationship 464 epSOSPregnancyInformation 466 epSOSProcedures 467 epSOSReactionAllergy 470 epSOSResolutionOutcome 472 epSOSRoleClass 473 epSOSRouteofAdministration 474 epSOSSections 477 epSOSSeverity 478 epSOSSocialHistory 479 epSOSStatusCode 480 epSOSSubstitutionCode 481 epSOSTelecomAddress 482 epSOSTimingEvent 483 epSOSUnits 484 epSOSUnknownInformation 487 epSOSVaccine 488 © eHealth DSI eHDSI Solution Provider v2.2.2-OR Wed Nov 08 16:16:10 CET 2017 Page 3 of 490 MTC epSOSActiveIngredient epSOSActiveIngredient Value Set ID 1.3.6.1.4.1.12559.11.10.1.3.1.42.24 TRANSLATIONS Code System ID Code System Version Concept Code Description (FSN) 2.16.840.1.113883.6.73 2017-01 A ALIMENTARY TRACT AND METABOLISM 2.16.840.1.113883.6.73 2017-01 -

Elif Fatma Sen BW.Indd

Use and Safety of Respiratory Medicines in Children E. F. Şen EEliflif FFatmaatma SSenen BBW.inddW.indd 1 003-01-113-01-11 115:175:17 The work presented in this thesis was conducted at the Department of Medical Informatics of the Erasmus University Medical Center, Rotterdam. The research reported in thesis was funded by the European Community’s 6th Framework Programme. Project number LSHB-CT-2005-005216: TEDDY: Task force in Europe for Drug Development for the Young. The contributions of the participating primary care physicians in the IPCI, Pedianet and IMS-DA project are greatly acknowledged. Financial support for printing this thesis was kindly provided by the department of Medical Informatics – Integrated Primary Care Information (IPCI) project of the Erasmus University Medi- cal Center; and by the J.E. Jurriaanse Stichting in Rotterdam. Cover: Optima Grafi sche Communicatie Printed by: Optima Grafi sche Communicatie Elif Fatma Şen Use and Safety of Respiratory medicines in Children ISBN: 978-94-6169-003-6 © E.F. Şen, Rotterdam, the Netherlands, 2011. All rights reserved. No part of this thesis may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, without prior written permission of the holder of the copyright. EEliflif FFatmaatma SSenen BBW.inddW.indd 2 003-01-113-01-11 115:175:17 Use and Safety of Respiratory Medicines in Children Het gebruik en de bijwerkingen van respiratoire medicijnen in kinderen Proefschrift Ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor aan de Erasmus Universiteit Rotterdam op gezag van de rector magnifi cus Prof.dr. -

Estonian Statistics on Medicines 2016 1/41

Estonian Statistics on Medicines 2016 ATC code ATC group / Active substance (rout of admin.) Quantity sold Unit DDD Unit DDD/1000/ day A ALIMENTARY TRACT AND METABOLISM 167,8985 A01 STOMATOLOGICAL PREPARATIONS 0,0738 A01A STOMATOLOGICAL PREPARATIONS 0,0738 A01AB Antiinfectives and antiseptics for local oral treatment 0,0738 A01AB09 Miconazole (O) 7088 g 0,2 g 0,0738 A01AB12 Hexetidine (O) 1951200 ml A01AB81 Neomycin+ Benzocaine (dental) 30200 pieces A01AB82 Demeclocycline+ Triamcinolone (dental) 680 g A01AC Corticosteroids for local oral treatment A01AC81 Dexamethasone+ Thymol (dental) 3094 ml A01AD Other agents for local oral treatment A01AD80 Lidocaine+ Cetylpyridinium chloride (gingival) 227150 g A01AD81 Lidocaine+ Cetrimide (O) 30900 g A01AD82 Choline salicylate (O) 864720 pieces A01AD83 Lidocaine+ Chamomille extract (O) 370080 g A01AD90 Lidocaine+ Paraformaldehyde (dental) 405 g A02 DRUGS FOR ACID RELATED DISORDERS 47,1312 A02A ANTACIDS 1,0133 Combinations and complexes of aluminium, calcium and A02AD 1,0133 magnesium compounds A02AD81 Aluminium hydroxide+ Magnesium hydroxide (O) 811120 pieces 10 pieces 0,1689 A02AD81 Aluminium hydroxide+ Magnesium hydroxide (O) 3101974 ml 50 ml 0,1292 A02AD83 Calcium carbonate+ Magnesium carbonate (O) 3434232 pieces 10 pieces 0,7152 DRUGS FOR PEPTIC ULCER AND GASTRO- A02B 46,1179 OESOPHAGEAL REFLUX DISEASE (GORD) A02BA H2-receptor antagonists 2,3855 A02BA02 Ranitidine (O) 340327,5 g 0,3 g 2,3624 A02BA02 Ranitidine (P) 3318,25 g 0,3 g 0,0230 A02BC Proton pump inhibitors 43,7324 A02BC01 Omeprazole -

Topical Pain Management Order Form

Topical Pain Management Order Form Patient Name:______________________________________ Doctor Name: ________________________________________ Address: _______________________________________ Address: _______________________________________ City: ______________State: __________ Zip: ___________ City: _________________ State: ______ Zip: _________ DOB: ________________ Allergies: ___________________ DEA# ________________ NPI # ___________________ Phone Number: ( ) ______________________________ Ofce Phone: ( ) ______________ Contact: _____________ New Patients: Fax current insurance information with Rx COMMON FORMULATIONS: * NOTE: CROSS OUT ANY UNWANTED MEDICATIONS IF NOT DESIRED * ANTI-INFLAMMATORY CREAMS _____ CASCADE DICLOFENAC 3% BACLOFEN 2% (CDB ) For (ARTHRITIS-TENDONITIS-PLANTAR FASCITIS-EPICONDYLITIS) _____ CASCADE DICLOFENAC 3% BACLOFEN 2% CYCLOBENZ, 2% TETRACAINE 2% (BCDT) (MUSCULOSKELETAL) NEUROPATHIC PAIN CREAMS **NOTE: KETAMINE IS CONTROLLED SCHEDULE III, SUBSTITUTE AMANTADINE 8%, IF DESIRED. _____ KETAMINE 10%-BACLOFEN 2%-CYCLOBENZAPRINE 2%-GABAPENTIN 6%-LIDOCAINE 5% (KBCGL) _____ KETAMINE 10%-CLONIDINE 0.2%-GABAPENTIN 6%-IMIPRAMINE 3%-MEFENAMIC ACID 3%-TETRACAINE 2% (KCGIMT) CREAM (RSD/CRPS-TRIGEMINAL NEURALGIA-PHANTOM LIMB PAIN-DEVELOPING NEUROPATHY) _____ KETAMINE 10%-BACLOFEN 2%-GABAPENTIN 6%-IMIPRAMINE 3%-NIFEDIPINE 2%-TETRACAINE 2% (KBGINT) ( DIABETIC & CHEMOTHERAPY INDUCED PERIPHERAL NEUROPATHY) COMBINATION PAIN CREAMS _____ DICLOFENAC 3%-BACLOFEN 2%-CYCLOBENZAPRINE 2%-GABAPENTIN 6%-TETRACAINE 2% (DBCGT) (TMJ, MUSCULOSKELETAL