BROADCAST SYNDICATION in Broadcasting, Syndication Is The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

WILE MOTORS WE HAVE 8 Hatchback Sport Coupe New Carpeting, Great $5,000 After a Judge Noted He Had Location, Wolking Dis New *8380"" Shown No Remorse

fr ?4 — MANCHESTER HERALD, Friday, Jan. 13. 1989 APARTMENTS Merchandise I MISCELLANEOUS CARS (FOR RENT FOR SALE FOR SALE EAST HARTFORD. EIGHT month old water- 1980 FORD. Fairmont. Clean, second floor, 5 1 Spcciolisj^j bed, $325. Courthouse Four cylinder, four rooms, 2 bedrooms. I FURNITURE One Gold membership, speed. Runs and looks J Stove and refrigerator. 12'/2 months left tor good. Asking $500. 649- Security required. $650 5434. PORTABLE twin bed. ■^BOOKKEEPING/ $450. Compared to rep- plus utilities. Coll 644- Like new. Includes ■^CARPENTRY/ ■^HEATING/ MISCELLANEOUS ulor price of $700 plus. 1984 MERCURY Marquis. 1712.________________ mattress. $75. 643-8208. E ^ income tax 1 2 ^ REMODELING IS H J PLUMBING SERVICES Eric 649-3426.D One owner. Excellent TWO bedroom with heat condition. 39,000 miles. A on first floor. $600 per I FUEL OIL/COAL/ Fully equipped. $5395. SA5 HOME GSL Building Mainte 633-2824. month. No pets. One Ifirew ooo 1 9 8 8 INCOME TAXES PJ’s Plumblna, Heating 8 nance Co. Commercl- Automotive months security. Coll IMPR0VEMENT5 1984 RENAULT Encore. Consultation / Preparation & REPAIRS Air Conditioning al/ResIdentlal building Don, 643-2226, leoye SEA SO N ED firewood for Boilers, pumps, hot water repairs and home Im Five door, five speed. message. After 7pm, Individuals / "No Job Too Small" tanks, new and air conditioning, body sale. Cut, split and Regleleted and FuSy Insured provements. Interior 646-9892.____________ delivered. $35 per laad. Sole Proprietors replacements, and exterior painting, excellent, new muffler, MANCHESTER. Two 742-1182. FREE ESTIMATES FREE ESTIMATES light carpentry. Com I0 F O R S A L E tires. -

View / Open Bratslavsky Oregon 0171A 10830

FROM EPHEMERAL TO LEGITIMATE: AN INQUIRY INTO TELEVISION’S MATERIAL TRACES IN ARCHIVAL SPACES, 1950s -1970s by LAUREN MICHELLE BRATSLAVSKY A DISSERTATION Presented to the School of Journalism and Communication and the Graduate School of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy September 2013 DISSERTATION APPROVAL PAGE Student: Lauren Michelle Bratslavsky Title: From Ephemeral to Legitimate: An Inquiry into Television’s Material Traces in Archival Spaces, 1950s -1970s This dissertation has been accepted and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctor of Philosophy degree in the School of Journalism and Communication by: Dr. Janet Wasko Chairperson Dr. Carol Stabile Core Member Dr. Julianne Newton Core Member Dr. Daniel Pope Institutional Representative and Kimberly Andrews Espy Vice President for Research and Innovation; Dean of the Graduate School Original approval signatures are on file with the University of Oregon Graduate School. Degree awarded September 2013 ii © 2013 Lauren M. Bratslavsky This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs (United States) License. iii DISSERTATION ABSTRACT Lauren Michelle Bratslavsky Doctor of Philosophy School of Journalism and Communication September 2013 Title: From Ephemeral to Legitimate: An Inquiry into Television’s Material Traces in Archival Spaces, 1950s -1970s The dissertation offers a historical inquiry about how television’s material traces entered archival spaces. Material traces refer to both the moving image products and the assortment of documentation about the processes of television as industrial and creative endeavors. By identifying the development of television-specific archives and collecting areas in the 1950s to the 1970s, the dissertation contributes to television studies, specifically pointing out how television materials were conceived as cultural and historical materials “worthy” of preservation and academic study. -

E Dating Show, Visiter Des Musées, Les Sorties, Danser, Restaurant, Les Joies De La Vie Ave

Check out A&E's shows lineup. Find show info, videos, and exclusive content on A&E. Dating Show Auditions for in If you are looking to star in a reality show that can help you find your true love this is your category. Often times it can be difficult to meet a person that you feel that you want to spend your life with. It is even more rare when people have the opportunity to find this person of their dreams on a dating show. Dec 12, · E! has ordered 20 half-hour episodes of Dating #NoFilter, a new comedy blind dating series from Lime Pictures and All3Media America, for premiere next month. Dating #NoFilter will air Monday throug Author: Denise Petski. Betsie, 66 ans. Habite à Béthune, Pas-de-Calais, Nord-Pas-de-Calais. Recherche une femme: Amitié. Nouvelle sur ce site, aime les ballades, le cinéma E Dating Show, visiter des musées, les sorties, danser, restaurant, les joies de la vie ave. Jan 30, · Instead, it’s an absolute shit show of X-rated pics, ghosting and one night stands. Finally, an honest voice is coming to take on modern TV dating. Welcome to Dating #NoFilter. About E. Dec 18, · E! is on the Pulse of Pop Culture, bringing fans the very best original content including reality series, topical programming, exclusive specials, breaking entertainment news, and more. On this reality dating show, young singles head to paradise to find their perfect matches and for a chance to split the $1 million prize. related shows Ex On The Beach. -

Media Ownership Rules

05-Sadler.qxd 2/3/2005 12:47 PM Page 101 5 MEDIA OWNERSHIP RULES It is the purpose of this Act, among other things, to maintain control of the United States over all the channels of interstate and foreign radio transmission, and to provide for the use of such channels, but not the ownership thereof, by persons for limited periods of time, under licenses granted by Federal author- ity, and no such license shall be construed to create any right, beyond the terms, conditions, and periods of the license. —Section 301, Communications Act of 1934 he Communications Act of 1934 reestablished the point that the public airwaves were “scarce.” They were considered a limited and precious resource and T therefore would be subject to government rules and regulations. As the Supreme Court would state in 1943,“The radio spectrum simply is not large enough to accommodate everybody. There is a fixed natural limitation upon the number of stations that can operate without interfering with one another.”1 In reality, the airwaves are infinite, but the govern- ment has made a limited number of positions available for use. In the 1930s, the broadcast industry grew steadily, and the FCC had to grapple with the issue of broadcast station ownership. The FCC felt that a diversity of viewpoints on the airwaves served the public interest and was best achieved through diversity in station ownership. Therefore, to prevent individuals or companies from controlling too many broadcast stations in one area or across the country, the FCC eventually instituted ownership rules. These rules limit how many broadcast stations a person can own in a single market or nationwide. -

He KMBC-ÍM Radio TEAM

l\NUARY 3, 1955 35c PER COPY stu. esen 3o.loe -qv TTaMxg4i431 BItOADi S SSaeb: iiSZ£ (009'I0) 01 Ff : t?t /?I 9b£S IIJUY.a¡:, SUUl.; l: Ii-i od 301 :1 uoTloas steTaa Rae.zgtZ IS-SN AlTs.aantur: aTe AVSí1 T E IdEC. 211111 111111ip. he KMBC-ÍM Radio TEAM IN THIS ISSUE: St `7i ,ytLICOTNE OSE YN in the 'Mont Network Plans AICNISON ` MAISHAIS N CITY ive -Film Innovation .TOrEKA KANSAS Heart of Americ ENE. SEDALIA. Page 27 S CLINEON WARSAW EMROEIA RUTILE KMBC of Kansas City serves 83 coun- 'eer -Wine Air Time ties in western Missouri and eastern. Kansas. Four counties (Jackson and surveyed by NARTB Clay In Missouri, Johnson and Wyan- dotte in Kansas) comprise the greater Kansas City metropolitan trading Page 28 Half- millivolt area, ranked 15th nationally in retail sales. A bonus to KMBC, KFRM, serv- daytime ing the state of Kansas, puts your selling message into the high -income contours homes of Kansas, sixth richest agri- Jdio's Impact Cited cultural state. New Presentation Whether you judge radio effectiveness by coverage pattern, Page 30 audience rating or actual cash register results, you'll find that FREE & the Team leads the parade in every category. PETERS, ñtvC. Two Major Probes \Exclusive National It pays to go first -class when you go into the great Heart of Face New Senate Representatives America market. Get with the KMBC -KFRM Radio Team Page 44 and get real pulling power! See your Free & Peters Colonel for choice availabilities. st SATURE SECTION The KMBC - KFRM Radio TEAM -1 in the ;Begins on Page 35 of KANSAS fir the STATE CITY of KANSAS Heart of America Basic CBS Radio DON DAVIS Vice President JOHN SCHILLING Vice President and General Manager GEORGE HIGGINS Year Vice President and Sally Manager EWSWEEKLY Ir and for tels s )F RADIO AND TV KMBC -TV, the BIG TOP TV JIj,i, Station in the Heart of America sú,\.rw. -

The BG News February 13, 1987

Bowling Green State University ScholarWorks@BGSU BG News (Student Newspaper) University Publications 2-13-1987 The BG News February 13, 1987 Bowling Green State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/bg-news Recommended Citation Bowling Green State University, "The BG News February 13, 1987" (1987). BG News (Student Newspaper). 4620. https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/bg-news/4620 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University Publications at ScholarWorks@BGSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in BG News (Student Newspaper) by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@BGSU. Spirits and superstitions in Friday Magazine THE BG NEWS Vol. 69 Issue 80 Bowling Green, Ohio Friday, February 13,1987 Death Funding cut ruled for 1987-88 Increase in fees anticipated suicide by Mike Amburgey said. staff reporter Dalton said the proposed bud- get calls for $992 million Man kills wife, The Ohio Board of Regents statewide in educational subsi- has reduced the University's dies for 1987-88, the same friend first instructional subsidy allocation amount funded for this year. A for 1987-88 by $1.9 million, and 4.7 percent increase is called for by Don Lee unless alterations are made in in the academic year 1988-89 Governor Celeste's proposed DALTON SAID given infla- wire editor budget, University students tionary factors, the governor's could face at least a 25 percent budget puts state universities in The manager of the Bowling instructional fee increase, a difficult place. -

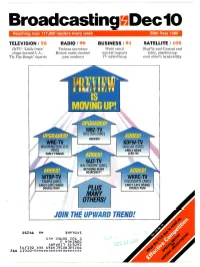

Broadcastingodec10 Reaching Over 117,000 Readers Every Week 60Th Year 1990

BroadcastingoDec10 Reaching over 117,000 readers every week 60th Year 1990 TELEVISION / 56 RADIO / 96 BUSINESS / 91 SATELLITE / 105 INTV: `Little train' Tribune examines Weak retail SkyPix and Comsat end chugs toward L.A.; British radio channel market impacts talks, questioning Tic Tac Dough' departs joint ventures TV advertising each other's bankability ' l WBZ -TV BOSTON (NBC) ACCESS! KDFW -TV DALLAS (CBS) EARLY NEWS LEAD -IN! WJZ -TV BALTIMORE (ABC) NETWORK NEWS DOW ADJACENCY! WISP -TV WKRC -TV TAMPA (ABC) CINCINNATI (ABC) EARLY -LATE FRINGE EARLY -LATE FRINGE DOUBLE RUN! PLUS DOUBLE RUN! MANY OTHERS! JOIN THE UPWARD TREND! 65266 VM 3NV)IOdS 3AV 3NOOfl ZO S 3 n VOV 7N05 AäV2l8I l At SU87 T6/030 )13A 68663qS0ä3E15266 266 I I01 G-f:********* * *, **= *w RELEASED FROM CROSBY LIBRARY GONZAGA UNIVERSITY I hear Warner Bros. is already on the road with something big in first-run for the fall. Is that so? r 1\2_1jrßr-á D2 has expanded the li It was only a matter of time. Now Sony D-2 Now it can cc composite digital video offers broadcasters some- thing they've been waiting for. Time compression. It's an option now available on the DVR -18, Sony's c three hour D -2 VTR. c The DVR -18's time With the DVR-18's optional time e compression, you can squeeze more out of the time you've got. e compression and expansion feature is remarkably advanced. A single plug -in module provides full audio data recovery as well as precise digital pitch correction for two stereo pairs of audio signals at The DVR -18 gives you ti the same time. -

Broadcast Syndication Broadcast Syndication

Broadcast Syndication Broadcast Syndication SYNDICATION SYNDICATIONStations Clearances SYNDICATION182 stations / 78.444% DMA %US MARKET HouseHolds Stations Affiliates Channel Air Time 1 6.468 NEW YORK 6,701,760 WVVH Independent 50 SUN 2PM 1 NEW YORK WMBC Independent 18 SUN 2PM 1 NEW YORK WRNN Independent 48 SUN 2PM 2 4.917 LOS ANGELES 5,113,680 KXLA Independent 44 SUN 2PM 3 3.047 CHICAGO 3,142,880 WBBM CBS 2 3 CHICAGO WSPY Independent 32 SUN 2PM 4 2.611 PHILADELPHIA 2,715,440 WACP Independent 4 4 PHILADELPHIA WPSJ Independent 8 SUN 2PM 4 PHILADELPHIA WZBN Independent 25 SUN 2PM 5 2.243 DALLAS 2,332,720 KHPK Independent 28 SUN 2PM 5 DALLAS KTXD Independent 46 6 2.186 SAN FRANCISCO 7 2.076 BOSTON 2,159,040 WBIN Independent 35 7 BOSTON WHDN Independent 26 8 2.059 WASHINGTON DC 2,141,360 WJAL Independent 68 9 2.000 ATLANTA 2,080,000 WANN Independent 32 SUN 2PM 10 1.906 HOUSTON 1,953,120 KUVM Independent 34 SUN 2PM 10 HOUSTON KHLM Independent 43 SUN 2PM 10 HOUSTON KETX Independent 28 SUN 2PM 11 1.607 DETROIT 12 1.580 SEATTLE 1,681,680 KUSE Independent 46 SUN 2PM 12 SEATTLE KPST Independent 66 SUN 2PM 13 1.580 PHOENIX 1,643,200 KASW CW 49 SUN 5AM 13 PHOENIX KNJO Independent 15 SUN 2PM 13 PHOENIX KKAX Independent 36 SUN 2PM 13 PHOENIX KCFG Independent 32 SUN 2PM 14 1.560 TAMPA 1,622,400 WWSB ABC 24 15 1.502 MINNEAPOLIS 1,562,080 KOOL Independent 21 16 1.381 MIAMI 1,332,240 WHDT Independent 9 17 1.351 DENVER 1,405,040 KDEO Independent 23 SUN 2PM 17 DENVER KTED Independent 25 SUN 2PM 18 1.321 CLEVELAND 1,373,840 WBNX CW 30 18 CLEVELAND WMFD Independent 12 SUN 2PM 19 1.278 ORLANDO 1,329,120 WESH NBC 11 19 ORLANDO WHDO Independent 38 20 1.211 SACRAMENTO 1,259,440 KBTV Independent 8 SUN 2PM 21 1.094 ST. -

Transatlantic Spaces: Production, Location and Style in 1960S-1970S Action- Adventure TV Series

Transatlantic spaces: production, location and style in 1960s-1970s action- adventure TV series Article Accepted Version Bignell, J. (2010) Transatlantic spaces: production, location and style in 1960s-1970s action-adventure TV series. Media History, 16 (1). pp. 53-65. ISSN 1469-9729 doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/13688800903395460 Available at http://centaur.reading.ac.uk/17666/ It is advisable to refer to the publisher’s version if you intend to cite from the work. See Guidance on citing . To link to this article DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13688800903395460 Publisher: Taylor & Francis All outputs in CentAUR are protected by Intellectual Property Rights law, including copyright law. Copyright and IPR is retained by the creators or other copyright holders. Terms and conditions for use of this material are defined in the End User Agreement . www.reading.ac.uk/centaur CentAUR Central Archive at the University of Reading Reading’s research outputs online Transatlantic spaces: Production, location and style in 1960s-70s Action-Adventure TV Series Jonathan Bignell Abstract This article argues that transatlantic hybridity connects space, visual style and ideological point of view in British television action-adventure fiction of the 1960s-70s. It analyses the relationship between the physical location of TV series production at Elstree Studios, UK, the representation of place in programmes, and the international trade in television fiction between the UK and USA. The TV series made at Elstree by the ITC and ABC companies and their affiliates linked Britishness with an international modernity associated with the USA, while also promoting national specificity. To do this, they drew on film production techniques that were already common for TV series production in Hollywood. -

THE WRITE CHOICE by Spencer Rupert a Thesis Presented to The

THE WRITE CHOICE By Spencer Rupert A thesis presented to the Independent Studies Program of the University of Waterloo in fulfilment of the thesis requirements for the degree Bachelor of Independent Studies (BIS) Waterloo, Canada 2009 1 Table of Contents 1 Abstract...................................................................................................................................................7 2 Summary.................................................................................................................................................8 3 Introduction.............................................................................................................................................9 4 Writing the Story...................................................................................................................................11 4.1 Movies...........................................................................................................................................11 4.1.1 Writing...................................................................................................................................11 4.1.1.1 In the Beginning.............................................................................................................11 4.1.1.2 Structuring the Story......................................................................................................12 4.1.1.3 The Board.......................................................................................................................15 -

What Is a Lighting Director?

What is a lighting director by Martin Kempton What is a lighting director? Simply put - a lighting director designs the lighting for multi-camera television productions. He or she instructs the crew of electricians in their work in addition to guiding the team of operators who usually sit with the LD in the lighting control room. All this while working closely with the director and the rest of the production team to deliver the best possible pictures. However, there's rather more to it than that, and on this page on the website I explain where LDs work, what kinds of shows LDs work on and give some of the background to what we do. It's important to point out right away that simple 'illumination' is actually a relatively unimportant part of our work. Current TV cameras are capable of operating in very low light levels so it would be quite possible to see what was going on in most studios simply by switching on the houselights. Fortunately, producers and directors realise that the result would look pretty awful. Another thing is also worth making clear – a lighting director is not an electrician. He or she might have been once, but an LD is not another name for a crew chief or gaffer. Most television LDs do not have electrical qualifications, although some may have. In any case, this is not a requirement of the job. The electrical supervisor (gaffer) is in charge of realising the LD’s design in the studio from the rigging and electrical point of view. -

Transition to BLIND DATE Video

Going on a date What is the definition of a “date”? (Oxford English Dictionary) • 1. A date = (n.) A social or romantic appointment or engagement. • 2. A date = (n.) A person with whom one has a date. Examples of a date?! What is a “blind date” ? • blind = (adj.) unable to see • A blind date is a social meeting between two people who have not met before (usually arranged by a mutual acquaintance). Examples of a blind date?! BLIND DATE : the famous TV show Can you explain what happens on this show?... BLIND DATE : what happens on the show… 1. Three singles of the same sex are introduced to the audience. 2. They are then questioned by a single of the opposite sex, who can hear but not see them (because hidden behind a screen), to choose with whom to go on a date. 3. Before the decision, Graham, who is never seen, gives an amusing reminder of each contestant. (Graham is a “voice over” = “voix off” in French.) 4. The couple then picks an envelope naming their destination for their date. 5. The following episode, a week later, shows the couple on their date, and interviews with them about the date and about each other. What questions do you think are asked on the Blind Date TV show ? • Name? • What’s your name? • Origins? • Where do you come from? / Where are you from? • Occupation? • What do you do (for a living)? • Likes? • What do you like (doing)? / What are your turn ons? • Dislikes? • What don’t you like (doing)? / What are your turn offs? Blind Date Special with Mr Bean •In 1993, Mr Bean (played by Rowan Atkinson) made a guest appearance on the show.