The De Minimis Doctrine in the Context of Sampling Copyright-Protected Sound Recordings in New Music

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Annotated Bibliography of Current Research in the Field of the Medical Problems of Trumpet Playing

AN ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY OF CURRENT RESEARCH IN THE FIELD OF THE MEDICAL PROBLEMS OF TRUMPET PLAYING D.M.A. Document Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Musical Arts in the Graduate School at The Ohio State University By Mark Alan Wade, B.M., M.M. ***** The Ohio State University 2008 Document Committee: Professor Timothy Leasure, Adviser Approved by Professor Alan Green Dr. Russel Mikkelson ________________________ Adviser Graduate Program in Music ABSTRACT The very nature of the lifestyle of professional trumpet players is conducive to the occasional medical problem. The life-hours of diligent practice and performance that make a performer capable of musical expression on the trumpet also can cause a host of overuse and repetitive stress ailments. Other medical problems can arise through no fault of the performer or lack of technique, such as the brain disease Task-Specific Focal Dystonia. Ailments like these fall into several large categories and have been individually researched by medical professionals. Articles concerning this narrow field of research are typically published in their respective medical journals, such as the Journal of Applied Physiology . Articles whose research is pertinent to trumpet or horn, the most similar brass instruments with regard to pitch range, resistance and the intrathoracic pressures generated, are often then presented in the instruments’ respective journals, ITG Journal and The Horn Call. Most articles about the medical problems affecting trumpet players are not published in scholarly music journals such as these, rather, are found in health science publications. Herein lies the problem for both musician and doctor; the wealth of new information is not effectively available for dissemination across fields. -

Managing the Boundaries of Taste: Culture, Valuation, and Computational Social Science* Ryan Light University of Oregon Colin Od

Managing the Boundaries of Taste: Culture, Valuation, and Computational Social Science* Ryan Light University of Oregon Colin Odden Ohio State University Ohio Colleges of Medicine This is a pre-copyedited, author-produced version of an article accepted for publication in Social Forces following peer review. The version of record is available online at: https://doi.org/10.1093/sf/sox055. *Please direct all correspondence to Ryan Light, [email protected]. The authors thank James Moody, Jill Ann Harrison, Matthew Norton, Brandon Stewart, Achim Edelmann, Clare Rosenfeld Evans, Jordan Besek, and Brian Ott for their helpful comments on earlier drafts of this paper. Managing the Boundaries of Taste: Culture, Valuation, and Computational Social Science Abstract The proliferation of cultural objects, such as music, books, film and websites, has created a new problem: How do consumers determine the value of cultural objects in an age of information glut? Crowd-sourcing – paralleling word-of-mouth recommendations – has taken center stage, yet expert opinion has also assumed renewed importance. Prior work on the valuation of artworks and other cultural artifacts identifies ways critics establish and maintain classificatory boundaries, such as genre. We extend this research by offering a theoretical approach emphasizing the dynamics of critics’ valuation and classification. Empirically, this analysis turns to Pitchfork.com, an influential music review website, to examine the relationship between classification and valuation. Using topic models of fourteen years of Pitchfork.com album reviews (n=14,495), we model the dynamics of valuation through genre and additional factors predictive of positive reviews and cultural consecration. We use gold record awards to study the relationship between valuation processes and commercial outcomes. -

My Bloody Valentine's Loveless David R

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2006 My Bloody Valentine's Loveless David R. Fisher Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF MUSIC MY BLOODY VALENTINE’S LOVELESS By David R. Fisher A thesis submitted to the College of Music In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Music Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2006 The members of the Committee approve the thesis of David Fisher on March 29, 2006. ______________________________ Charles E. Brewer Professor Directing Thesis ______________________________ Frank Gunderson Committee Member ______________________________ Evan Jones Outside Committee M ember The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Tables......................................................................................................................iv Abstract................................................................................................................................v 1. THE ORIGINS OF THE SHOEGAZER.........................................................................1 2. A BIOGRAPHICAL ACCOUNT OF MY BLOODY VALENTINE.………..………17 3. AN ANALYSIS OF MY BLOODY VALENTINE’S LOVELESS...............................28 4. LOVELESS AND ITS LEGACY...................................................................................50 BIBLIOGRAPHY..............................................................................................................63 -

ALLA Press Release May 26 2015 FINAL

! ! ! A$AP ROCKY’S NEW ALBUM AT.LONG.LAST.A$AP AVAILABLE NOW ON A$AP WORLDWIDE/POLO GROUNDS MUSIC/RCA RECORDS TRENDING NO. 1 ON ITUNES IN THE US, UK, CANADA, AUSTRALIA, FRANCE, GERMANY AND MORE SOPHOMORE ALBUM FEATURES APPEARANCES BY KANYE WEST, LIL WAYNE, ScHOOLBOY Q, MIGUEL, ROD STEWART, MARK RONSON, MOS DEF, JUICY J, JOE FOX AND OTHERS [New York, NY – May 26, 2015] A$AP Rocky released his highly anticipated new album, At.Long.Last.A$AP, today (5/26) due to the album leaking a week prior to its scheduled June 2nd release date. The album is currently No. 1 at iTunes in the US, UK, Canada, Australia, France, Germany, Denmark, Finland, New Zealand, Poland, Switzerland, Russia and more. The follow-up to the charismatic Harlem MC’s 2013 release, Long.Live.A$AP, A$AP Rocky’s sophomore album, features a stellar line up of guest appearances by Rod Stewart, Miguel and Mark Ronson on “Everyday,” ScHoolboy Q on “Electric Body,” Lil Wayne on a new version of the previously released “M’$,” Kanye West and Joe Fox on “Jukebox Joints,” plus Mos Def, Juicy J, UGK and more on other standout tracks. Producers Danger Mouse, Jim Jonsin, Juicy J and Mark Ronson among others, contributes to the album’s trippy new sound. Executive Producers include Danger Mouse, A$AP Yams and A$AP Rocky with Co-Executive Producers Hector Delgado, Juicy J, Chace Johnson, Bryan Leach and AWGE. In 2013, A$AP Rocky announced his global arrival in a major way with his chart- topping debut album LONG.LIVE.A$AP. -

Danny Krivit Salsoul Mix Mp3, Flac, Wma

Danny Krivit Salsoul Mix mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Funk / Soul Album: Salsoul Mix Country: Japan Released: 2003 Style: Disco MP3 version RAR size: 1298 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1590 mb WMA version RAR size: 1481 mb Rating: 4.7 Votes: 345 Other Formats: ASF AAC ADX WAV VOX MP4 RA Tracklist Hide Credits Everyman (Joe Claussell's Acapella Remix) 1 –Double Exposure Remix – Joe Claussell 2 –The Salsoul Orchestra Getaway 3 –Edwin Birdsong Win Tonight 4 –Instant Funk I Got My Mind Made Up (You Can Get It Girl) (Beat) Such A Feeling (Shep Pettibone 12" Mix) 5 –Aurra Remix – Shep Pettibone Falling In Love (DK Edit Of Shep Pettibone Remix) 6 –Surface Edited By – Danny KrivitRemix – Shep Pettibone 7 –First Choice Love Having You Around Moment Of My Life (DK Edit Of Shep Pettibone Remix) 8 –Inner Life Edited By – Danny KrivitRemix – Shep Pettibone 9 –Candido Dancin And Prancin 10 –Loleatta Holloway Dreamin (2nd Half With Accapella Ending) Let No Man Put Asunder (DK Medley Of Frankie Knuckles,Walter Gibbons & Shep Pettibone Remixes) 11 –First Choice Edited By – Danny KrivitRemix – Frankie Knuckles, Shep Pettibone, Walter Gibbons 12 –The Salsoul Orchestra 212 North 12th The Beat Goes On And On (Jim Burgess 12" Mix) 13 –Ripple Mixed By – Jim Burgess 14 –The Salsoul Orchestra How High (Original Version) Companies, etc. Manufactured By – Toshiba EMI Ltd Phonographic Copyright (p) – Salsoul Records Copyright (c) – Salsoul Records Phonographic Copyright (p) – Toshiba EMI Ltd Credits Design – Tats Ohisa DJ Mix – Danny Krivit Executive -

The Grey Album and Musical Composition in Configurable Culture

What Did Danger Mouse Do? The Grey Album and Musical Composition in Configurable Culture This article uses The Grey Album, Danger Mouse’s 2004 mashup of Jay-Z’s Black Album with the Beatles’“White Album,” to explore the ontological status of mashups, with a focus on determining what sort of creative work a mashup is. After situating the album in relation to other types of musical borrowing, I provide brief analyses of three of its tracks and build upon recent research in configurable-music practices to argue that the album is best conceptualized as a type of musical performance. Keywords: The Grey Album, The Black Album, the “White Album,” Danger Mouse, Jay-Z, the Beatles, mashup, configurable music. Downloaded from captions. What’s most embarrassing about this is how http://mts.oxfordjournals.org/ immensely improved both cartoons turned out to be.”2 n 1989 Gary Larson published The PreHistory of The Far Larson’s tantalizing use of quotation marks around “acci- Side, a retrospective of his groundbreaking cartoon. In a dentally” implies that the editor responsible for switching the I section of the book titled Mistakes—Mine and Theirs, captions may have done so deliberately. If we assume this to be Larson discussed a couple of curious instances when the Dayton the case and agree that both cartoons are improved, a number of Daily News switched the captions for The Far Side with the one questions emerge. What did the editor do? He/she did not for Dennis the Menace, its neighbor on the comics page. The come up with a concept, did not draw a cartoon, and did not first of these two instances had, by far, the funnier result: on the compose a caption. -

1 "Disco Madness: Walter Gibbons and the Legacy of Turntablism and Remixology" Tim Lawrence Journal of Popular Music S

"Disco Madness: Walter Gibbons and the Legacy of Turntablism and Remixology" Tim Lawrence Journal of Popular Music Studies, 20, 3, 2008, 276-329 This story begins with a skinny white DJ mixing between the breaks of obscure Motown records with the ambidextrous intensity of an octopus on speed. It closes with the same man, debilitated and virtually blind, fumbling for gospel records as he spins up eternal hope in a fading dusk. In between Walter Gibbons worked as a cutting-edge discotheque DJ and remixer who, thanks to his pioneering reel-to-reel edits and contribution to the development of the twelve-inch single, revealed the immanent synergy that ran between the dance floor, the DJ booth and the recording studio. Gibbons started to mix between the breaks of disco and funk records around the same time DJ Kool Herc began to test the technique in the Bronx, and the disco spinner was as technically precise as Grandmaster Flash, even if the spinners directed their deft handiwork to differing ends. It would make sense, then, for Gibbons to be considered alongside these and other towering figures in the pantheon of turntablism, but he died in virtual anonymity in 1994, and his groundbreaking contribution to the intersecting arts of DJing and remixology has yet to register beyond disco aficionados.1 There is nothing mysterious about Gibbons's low profile. First, he operated in a culture that has been ridiculed and reviled since the "disco sucks" backlash peaked with the symbolic detonation of 40,000 disco records in the summer of 1979. -

Client and Artist List

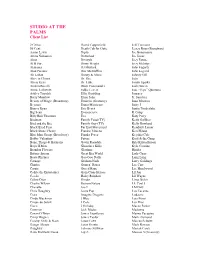

STUDIO AT THE PALMS Client List 2 Cellos David Copperfield Jeff Timmons 50 Cent Death Cab for Cutie Jersey Boys (Broadway) Aaron Lewis Diplo Joe Bonamassa Akina Nakamori Disturbed Joe Jonas Akon Divinyls Joey Fatone Al B Sure Dizzy Wright Joey McIntyre Alabama DJ Mustard John Fogarty Alan Parsons Doc McStuffins John Legend Ali Lohan Donny & Marie Johnny Gill Alice in Chains Dr. Dre JoJo Alicia Keys Dr. Luke Jordin Sparks Andrea Bocelli Duck Commander Josh Gracin Annie Leibovitz Eddie Levert Jose “Pepe” Quintano Ashley Tinsdale Ellie Goulding Journey Barry Manilow Elton John Jr. Sanchez Beauty of Magic (Broadway) Eminem (Grammy) Juan Montero Beyonce Ennio Morricone Juicy J Bianca Ryan Eric Benet Justin Timberlake Big Sean Evanescence K Camp Billy Bob Thornton Eve Katy Perry Birdman Family Feud (TV) Keith Galliher Bird and the Bee Family Guy (TV) Kelly Rowland Black Eyed Peas Far East Movement Kendrick Lamar Black Stone Cherry Frankie Moreno Keri Hilson Blue Man Group (Broadway) Franky Perez Keyshia Cole Bobby Valentino Future Kool & the Gang Bone, Thugs & Harmony Gavin Rossdale Kris Kristofferson Boyz II Men Ghostface Killa Kyle Cousins Brandon Flowers Gloriana Hinder Britney Spears Great Big World Lady Gaga Busta Rhymes Goo Goo Dolls Lang Lang Carnage Graham Nash Larry Goldings Charise Guns n’ Roses Lee Carr Cassie Gucci Mane Lee Hazelwood Cedric the Entertainer Gym Class Heroes Lil Jon Cee-lo Haley Reinhart Lil Wayne Celine Dion Hinder Limp Bizkit Charlie Wilson Human Nature LL Cool J Chevelle Ice-T LMFAO Chris Daughtry Icona Pop Los -

WXYC Brings You Gems from the Treasure of UNC's Southern

IN/AUDIBLE LETTER FROM THE EDITOR a publication of N/AUDIBLE is the irregular newsletter of WXYC – your favorite Chapel Hill radio WXYC 89.3 FM station that broadcasts 24 hours a day, seven days a week out of the Student Union on the UNC campus. The last time this publication came out in 2002, WXYC was CB 5210 Carolina Union Icelebrating its 25th year of existence as the student-run radio station at the University of Chapel Hill, NC 27599 North Carolina at Chapel Hill. This year we celebrate another big event – our tenth anni- USA versary as the first radio station in the world to simulcast our signal over the Internet. As we celebrate this exciting event and reflect on the ingenuity of a few gifted people who took (919) 962-7768 local radio to the next level and beyond Chapel Hill, we can wonder request line: (919) 962-8989 if the future of radio is no longer in the stereo of our living rooms but on the World Wide Web. http://www.wxyc.org As always, new technology brings change that is both exciting [email protected] and scary. Local radio stations and the dedicated DJs and staffs who operate them are an integral part of vibrant local music communities, like the one we are lucky to have here in the Chapel Hill-Carrboro Staff NICOLE BOGAS area. With the proliferation of music services like XM satellite radio Editor-in-Chief and Live-365 Internet radio servers, it sometimes seems like the future EDITOR-IN-CHIEF: Nicole Bogas of local radio is doomed. -

Thou Shalt Not Steal: Grand Upright Music Ltd. V. Warner Bros. Records, Inc. and the Future of Digital Sound Sampling in Popular Music, 45 Hastings L.J

Hastings Law Journal Volume 45 | Issue 2 Article 4 1-1994 Thou hS alt Not Steal: Grand Upright Music Ltd. v. Warner Bros. Records, Inc. and the Future of Digital Sound Sampling in Popular Music Carl A. Falstrom Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hastings_law_journal Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Carl A. Falstrom, Thou Shalt Not Steal: Grand Upright Music Ltd. v. Warner Bros. Records, Inc. and the Future of Digital Sound Sampling in Popular Music, 45 Hastings L.J. 359 (1994). Available at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hastings_law_journal/vol45/iss2/4 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Hastings Law Journal by an authorized editor of UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Thou Shalt Not Steal: Grand Upright Music Ltd. v. Warner Bros. Records, Inc. and the Future of Digital Sound Sampling in Popular Music by CARL A. FALSTROM* Introduction Digital sound sampling,1 the borrowing2 of parts of sound record- ings and the subsequent incorporations of those parts into a new re- cording,3 continues to be a source of controversy in the law.4 Part of * J.D. Candidate, 1994; B.A. University of Chicago, 1990. The people whom I wish to thank may be divided into four groups: (1) My family, for reasons that go unstated; (2) My friends and cohorts at WHPK-FM, Chicago, from 1986 to 1990, with whom I had more fun and learned more things about music and life than a person has a right to; (3) Those who edited and shaped this Note, without whom it would have looked a whole lot worse in print; and (4) Especially special persons-Robert Adam Smith, who, among other things, introduced me to rap music and inspired and nurtured my appreciation of it; and Leah Goldberg, who not only put up with a whole ton of stuff for my three years of law school, but who also managed to radiate love, understanding, and support during that trying time. -

March 20, 1982 FORIUNE MAGAZME ^APRODUCT OFIHEYEAR- MH/I MUSK TELEVISION

March 20, 1982 FORIUNE MAGAZME ^APRODUCT OFIHEYEAR- MH/i MUSK TELEVISION Of the countless products and services introduced in 1981, FORTUNE masazine chose just 10 that deserved special attention. And one of them was MTV: Music Television. MTV was sinsled out for providing a unique and innovative contribution to the American marketplace. But more than FORTUNE has smiled on us. Now MTV is a full member of the music community All around the industry the impact has been dramatic— on record retailers, radio programming, concert promotion. According to FORTUNE, video music on cable is big news. We’re working to make it big business— for us, and for all our friends in music. MUSIC TELEVISION Warner Amex Satellite Enterta inmen! Company © 1982 WASEC VOLUME XLIII — NUMBER 43 — March 20, 1982 THE INTERNATIONAL MUSIC RECORD WEEKLY dSH BOX GEORGE ALBERT President and Publisher NICK ALBARANO Vice President EDITORML Sneak Preview ALAN SUTTON In this time of economic hardship, perhaps a scious effort to add new product and accessory Vice PrestdenI and Editor In Chief lesson can be drawn from the independent retailers lines. While the emphasis is still on pre-recorded J.B. CARMICLE Vice President and General Manager. East Coast —the mom-and-pop stores that represent what may music, there is also a strong commitment to ex- JIM SHARP be the industry’s closest contact with the mass of perimenting with other leisure-related products. Vice President. Nashville As gets tighter and tighter and Without the major resources of corporate or chain RICHARD IMAMURA consumers. money Managing Editor sales refuse to improve, many of the mom-and- headquarters to provide a cushion, the mom-and- MARK ALBERT pops have had to adjust their outlook on the industry pops have had to make do with imagination, in- Marketing Director to stay afloat. -

Selected Discography

479 of 522 selected discography 6932 Lawrence / LOVE SAVES THE DAY / sheet The following discography lists all of the recordings referred to in Love Saves the Day. It provides basic information on the name of the artist, the title of the recording, the name of the label that originally released the recording, and the year in which the recording was first released. Entries are listed in alphabetical order, first according to the name of the artist, and subsequently according to the title of the recording. Albums are highlighted in italics, whereas individual album cuts, seven-inch singles, and twelve-inch singles are written in normal typeface. Abaco Dream. ‘‘Life and Death in G & A.’’ , . Area Code . ‘‘Stone Fox Chase.’’ Polydor, . Ashford & Simpson. ‘‘Found a Cure.’’ Warner Bros., . '.‘‘It Seems to Hang On.’’ Warner Bros., . '. ‘‘Over and Over.’’ Warner Bros., . '. ‘‘Stay Free.’’ Warner Bros., . Atmosfear. ‘‘Dancing in Outer Space.’’ Elite, . Auger, Brian, & the Trinity. ‘‘Listen Here.’’ , . Ayers, Roy, Ubiquity. ‘‘Don’t Stop the Feeling.’’ Polydor, . '. ‘‘Running Away.’’ Polydor, . Babe Ruth. ‘‘The Mexican.’’ Harvest, . Barrabas. Barrabas. , . '. ‘‘Wild Safari.’’ , . '. ‘‘Woman.’’ , . Barrow, Keith. ‘‘Turn Me Up.’’ Columbia, . Bataan, Joe. ‘‘Aftershower Funk.’’ Mericana, . '. ‘‘Latin Strut.’’ Mericana, . '. ‘‘Rap-O Clap-O.’’ Salsoul, . '. Salsoul. Mericana, . Bean, Carl. ‘‘I Was Born This Way.’’ Motown, . Beatles. ‘‘Here Comes the Sun.’’ Apple, . Tseng 2003.10.1 08:35 481 of 522 !. ‘‘It’s Too Funky in Here.’’ Polydor, . !. ‘‘Mother Popcorn (You Got to Have a Mother for Me).’’ King, . Brown, Peter. ‘‘Do Ya Wanna Get Funky With Me.’’ , . !. ‘‘Love in Our Hearts.’’ , . B. T. Express. ‘‘Do It (’Til You’re Satisfied).’’ Scepter, .