Fundamentals of Economic Principles and Wildlife Management

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wildlife Management in the National Parks

wildlife management IN THE NATIONAL PARKS wildlife management IN IHE NATIONAL PARKS 1969 REPRINT FROM ADMINISTRATIVE POLICIES FOR NATURAL AREAS OF THE NATIONAL PARK SYSTEM U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR • NATIONAL PARK SERVICE For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Washington, D.C. 20402 - Price 15 cents WILDLIFE MANAGEMENT IN THE NATIONAL PARKS ADVISORY BOARD ON WILDLIFE MANAGEMENT, APPOINTED BY SECRETARY OF THE INTERIOR UDALL A. S. Leopold (Chairman), S. A. Cain, C. M. Cottam, I. N. Gabrielson, T. L. Kimball March 4, 1963 Historical In the Congressional Act of 1916 which created the National Park Service, preservation of native animal' life was clearly specified as one of the pur poses of the parks. A frequently quoted passage of the Act states "... which purpose is to conserve the scenery and the natural and historic objects and the wild life therein and to provide for the enjoyment of the same in such manner and by such means as will leave them unimpaired for the enjoy ment of future generations." In implementing this Act, the newly formed Park Service developed a philosophy of wildlife protection, which in that era was indeed the most obvious and immediate need in wildlife conservation. Thus the parks were established as refuges, the animal populations were protected from wildfire. For a time predators were controlled to protect the "good" ani mals from the "bad" ones, but this endeavor mercifully ceased in the 1930's. On the whole, there was little major change in the Park Service practice of wildlife management during the first 40 years of its existence. -

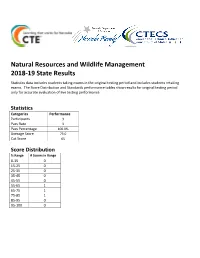

Natural Resources and Wildlife Management Statistics

Natural Resources and Wildlife Management 2018-19 State Results Statistics data includes students taking exams in the original testing period and includes students retaking exams. The Score Distribution and Standards performance tables show results for original testing period only for accurate evaluation of live testing performance. Statistics Categories Performance Participants 3 Pass Rate 3 Pass Percentage 100.0% Average Score 73.0 Cut Score 65 Score Distribution % Range # Scores in Range 0-15 0 15-25 0 25-35 0 35-45 0 45-55 0 55-65 1 65-75 1 75-85 1 85-95 0 95-100 0 Natural Resources and Wildlife Management 1) CONTENT STANDARD 1.0: EXPLORE NATURAL RESOURCE SCIENCE AND MANAGEMENT 75.93% 1) Performance Standard 1.1 : Investigate the Relationship Between Natural Resources and Society, Including Conflict Management 72.22% 1) 1.1.1 Define natural resource management 77.78% 3) 1.1.3 Describe human dependency and demands on natural resources 88.89% 4) 1.1.4 Explain natural resource conservation 66.67% 5) 1.1.5 Investigate the effects of multiple uses of natural resources (e.g., recreation, mining, agriculture, forestry, public lands grazing, etc.) 66.67% 6) 1.1.6 Analyze societal issues related to natural resource management 50% 2) Performance Standard 1.2 : Explain Interrelationships Between Natural Resources and Humans in Managing Natural Environments 86.67% 1) 1.2.1 Explain the effects and/or trade-off of population growth, greater energy consumption, and increased technology and development on natural resources and the environment 83.33% -

For-74: a Guide to Urban Habitat Conservation Planning

FOR-74 A Guide to Urban Habitat Conservation Planning Thomas G. Barnes, Extension Wildlife Specialist Lowell Adams, National Institute for Urban Wildlife entuckians value their forests and Kother natural resources for aes- Guidelines for Considering Wildlife in the Urban Development thetic, recreational, and economic Process significance, so over the past several Promote habitats that will have the food, cover, water, and living space that decades they have become increasingly all wildlife require by following these guidelines: concerned about the loss of wildlife • Before development, maximize open space and make an effort to protect the habitat and greenspace. Urban and most valuable wildlife habitat by placing buildings on less important portions suburban development is one of the of the site. Choosing cluster development, which is flexible, can help. leading causes of this loss: A recent • Provide water, and design stormwater control impoundments to benefit wildlife. study indicated that every day in • Use native plants that have value for wildlife as well as aesthetic appeal. Kentucky more than 100 acres of rural • Provide bird-feeding stations and nest boxes for cavity-nesting birds like land is being converted to urban house wrens and wood ducks. development. • Educate residents about wildlife conservation, using, for example, informa- Because concern for loss of tion packets or a nature trail through open space. greenspace is not new, we have for • Ensure a commitment to managing urban wildlife habitats. some time created attractive urban greenspace environments with our parks and backyards. These The publication can also be useful to A landscape is a large area com- greenspaces have been created not so the average homeowner in understand- posed of ecosystems (the plants, much for wildlife habitats as for people ing the complex issues involved in animals, other living organisms, and to enjoy, but the potential for wildlife landscape planning and wildlife their physical surroundings). -

Biodiversity Conservation and Habitat Management

CONTENTS BIODIVERSITY CONSERVATION AND HABITAT MANAGEMENT Biodiversity Conservation and Habitat Management - Volume 1 No. of Pages: 458 ISBN: 978-1-905839-20-9 (eBook) ISBN: 978-1-84826-920-0 (Print Volume) Biodiversity Conservation and Habitat Management - Volume 2 No. of Pages: 428 ISBN: 978-1-905839-21-6 (eBook) ISBN: 978-1-84826-921-7 (Print Volume) For more information of e-book and Print Volume(s) order, please click here Or contact : [email protected] ©Encyclopedia of Life Support Systems (EOLSS) BIODIVERSITY CONSERVATION AND HABITAT MANAGEMENT CONTENTS Preface xv VOLUME I Biodiversity Conservation and Habitat Management : An Overview 1 Francesca Gherardi, Dipartimento di Biologia Animale e Genetica, Università di Firenze, Italy Claudia Corti, California Academy of Sciences, San Francisco CA, U.S.A. Manuela Gualtieri, Dipartimento di Scienze Zootecniche, Università di Firenze, Italy 1. Introduction: the amount of biological diversity 2. Diversity in ecosystems 2.1. African wildlife systems 2.2. Australian arid grazing systems 3. Measures of biodiversity 3.1. Species richness 3.2. Shortcuts to monitoring biodiversity: indicators, umbrellas, flagships, keystones, and functional groups 4. Biodiversity loss: the great extinction spasm 5. Causes of biodiversity loss: the “evil quartet” 5.1. Over-harvesting by humans 5.2. Habitat destruction and fragmentation 5.3. Impacts of introduced species 5.4. Chains of extinction 6. Why conserve biodiversity? 7. Conservation biology: the science of scarcity 8. Evaluating the status of a species: extinct until proven extant 9. What is to be done? Conservation options 9.1. Increasing our knowledge 9.2. Restore habitats and manage them 9.3. -

Wildlife Management Activities and Practices

WILDLIFE MANAGEMENT ACTIVITIES AND PRACTICES COMPREHENSIVE WILDLIFE MANAGEMENT PLANNING GUIDELINES for the Edwards Plateau and Cross Timbers & Prairies Ecological Regions Revised April 2010 The following Texas Parks & Wildlife Department staff have contributed to this document: Mike Krueger, Technical Guidance Biologist – Lampasas Mike Reagan, Technical Guidance Biologist -- Wimberley Jim Dillard, Technical Guidance Biologist -- Mineral Wells (Retired) Kirby Brown, Private Lands and Habitat Program Director (Retired) Linda Campbell, Program Director, Private Lands & Public Hunting Program--Austin Linda McMurry, Private Lands and Public Hunting Program Assistant -- Austin With Additional Contributions From: Kevin Schwausch, Private Lands Biologist -- Burnet Terry Turney, Rare Species Biologist--San Marcos Trey Carpenter, Manager, Granger Wildlife Management Area Dale Prochaska, Private Lands Biologist – Kerr Wildlife Management Area Nathan Rains, Private Lands Biologist – Cleburne TABLE OF CONTENTS Comprehensive Wildlife Management Planning Guidelines Edwards Plateau and Cross Timbers & Prairies Ecological Regions Introduction Specific Habitat Management Practices HABITAT CONTROL EROSION CONTROL PREDATOR CONTROL PROVIDING SUPPLEMENTAL WATER PROVIDING SUPPLEMENTAL FOOD PROVIDING SUPPLEMENTAL SHELTER CENSUS APPENDICES APPENDIX A: General Habitat Management Considerations, Recommendations, and Intensity Levels APPENDIX B: Determining Qualification for Wildlife Management Use APPENDIX C: Wildlife Management Plan Overview APPENDIX D: Livestock -

Forest Conservation and Management in The

Management in a Changing Climate Policy Challenges for Wildlife Abstract: Try as it might, wildlife management cannot make wild living things adapt to climate change. Management can, Mark L. Shaffer however, make adaptation more or less likely. Given that pol- Office of the Science Advisor, icy is a rule set for action, policy will play a critical role in U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service society’s efforts to help wildlife cope with the challenge of cli- mate change. To be effective, policy must provide clear goals and be based on a clear understanding of the problem it seeks to affect. The “National Fish, Wildlife, and Plants Climate Ad- aptation Strategy” provides seven major goals and numerous policy related actions for wildlife management in a period of climate change. The underlying themes of these recommenda- tions and the major challenges to their achievement are identi- fied and discussed. INTRODUCTION As one of the major biome types on Earth, forests are of fundamental importance to wildlife. (Note: the term “wildlife” when used alone is meant as short hand for all species living in an undomesticated state: both plant and animal.) From the standpoint of species diversity, the most diverse terrestrial habitats on Earth are the great tropical rainforests. From the standpoint of sheer stand- ing biomass, the great temperate rainforest of the Pacific Northwest may be unequalled. In terms of charismatic megafauna, which for most people are the face of wild- life, many signature North American species (e.g., deer, bear, elk, wolf, moose, cougar) are principally forest spe- cies. A large fraction of the lands American society has chosen to devote to conservation are forested lands. -

Tech Rev 03-1 for PDF.Qxd

The Relationship of Economic Growth to Wildlife Conservation Gross National Product Gross Time THE WILDLIFE SOCIETY Technical Review 03-1 2003 THE RELATIONSHIP OF ECONOMIC GROWTH TO WILDLIFE CONSERVATION The Wildlife Society Members of the Economic Growth Technical Review Committee David L. Trauger (Chair) Pamela R. Garrettson Natural Resources Program Division of Migratory Bird Management Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Northern Virginia Center 11500 American Holly Drive 7054 Haycock Road Laurel, MD 20708 Falls Church, VA 22043 Brian J. Kernohan Brian Czech Boise Cascade Corporation National Wildlife Refuge System 2010 South Curtis Circle U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Boise, ID 83705 4401 North Fairfax Drive, MS 670 Arlington, VA 22203 Craig A. Miller Human Dimensions Research Program Jon D. Erickson Illinois Natural History Survey School of Natural Resources 607 East Peabody Drive Aiken Center Champaign, IL 61820 University of Vermont Burlington, VT 05405 Edited by Krista E. M. Galley The Wildlife Society Technical Review 03-1 5410 Grosvenor Lane, Suite 200 March 2003 Bethesda, Maryland 20814 Foreword Presidents of The Wildlife Society occasionally appoint ad hoc committees to study and report on select conservation issues. The reports ordinarily appear as either a Technical Review or a Position Statement. Review papers present technical information and the views of the appointed committee members, but not necessarily the views of their employers. Position statements are based on the review papers, and the preliminary versions are published in The Wildlifer for comment by Society members. Following the comment period, revision, and Council's approval, the statements are published as official positions of The Wildlife Society. -

Technical Review 12-04 December 2012

The North American Model of Wildlife Conservation Technical Review 12-04 December 2012 1 The North American Model of Wildlife Conservation The Wildlife Society and The Boone and Crockett Club Technical Review 12-04 - December 2012 Citation Organ, J.F., V. Geist, S.P. Mahoney, S. Williams, P.R. Krausman, G.R. Batcheller, T.A. Decker, R. Carmichael, P. Nanjappa, R. Regan, R.A. Medellin, R. Cantu, R.E. McCabe, S. Craven, G.M. Vecellio, and D.J. Decker. 2012. The North American Model of Wildlife Conservation. The Wildlife Society Technical Review 12-04. The Wildlife Society, Bethesda, Maryland, USA. Series Edited by Theodore A. Bookhout Copy Edit and Design Terra Rentz (AWB®), Managing Editor, The Wildlife Society Lisa Moore, Associate Editor, The Wildlife Society Maja Smith, Graphic Designer, MajaDesign, Inc. Cover Images Front cover, clockwise from upper left: 1) Canada lynx (Lynx canadensis) kittens removed from den for marking and data collection as part of a long-term research study. Credit: John F. Organ; 2) A mixed flock of ducks and geese fly from a wetland area. Credit: Steve Hillebrand/USFWS; 3) A researcher attaches a radio transmitter to a short-horned lizard (Phrynosoma hernandesi) in Colorado’s Pawnee National Grassland. Credit: Laura Martin; 4) Rifle hunter Ron Jolly admires a mature white-tailed buck harvested by his wife on the family’s farm in Alabama. Credit: Tes Randle Jolly; 5) Caribou running along a northern peninsula of Newfoundland are part of a herd compositional survey. Credit: John F. Organ; 6) Wildlife veterinarian Lisa Wolfe assesses a captive mule deer during studies of density dependence in Colorado. -

Social and Economic Considerations for Planning Wildlife Conservation in Large Landscapes 5 Robert G

CHAPTER Social and Economic Considerations for Planning Wildlife Conservation in Large Landscapes 5 Robert G. Haight and Paul H. Gobster People conserve wildlife for a variety of reasons. People conserve wildlife because they enjoy wildlife-related activities such as recreational hunting, wild- life viewing, or ecotourism that satisfy many personal and social values asso- ciated with people’s desire to connect with each other and with nature (Decker et al. 2001). People conserve wildlife because it provides tangible ben- efits such as food, clothing, and other products. People conserve wildlife because they recognize that species are integral parts of larger ecosystems that perform a number of valuable services including nutrient cycling, water purifi- cation, and climate regulation (Daily 1997). People also conserve wildlife for its option value or potential to produce future benefits, such as new pharmaceu- ticals (Fisher and Hanneman 1986). Finally, people conserve wildlife for its exis- tence value even if they will never see or use it (Bishop and Welsh 1992). Because wildlife provides benefits to the public at large, government agencies and private organizations take responsibility for wildlife conservation. Programs for wildlife conservation typically protect species and habitat from human activ- ities such as hunting, timber harvesting, or housing. As a result, conservation programs may impose substantial costs on other parts of society. Although it seems reasonable to evaluate conservation programs with an assessment of their benefits and costs, in practice, quantifying benefits is difficult, if not impossible. We are far from being able to obtain definitive estimates of wildlife benefits asso- ciated with nonconsumptive recreation activities, option values, existence values, and ecosystem services. -

Wildlife Management and Property Tax Valuation in Texas Larry A

Wildlife Management and Property Tax Valuation in Texas Larry A. Redmon, State Extension Forage Specialist, College Station James C. Cathey, Extension Wildlife Specialist, College Station Texas is known for its natural resources ranging from grasslands in the north, brushlands in the south, the piney woods in the east and the Chihuahuan desert in the west. These open space lands provide aesthetic and economic benefits through ecosystem services like recreation, water supply, carbon sequestration, and nutrient cycling. In order to preserve open space lands and their value to all Texans, qualifying properties may be taxed at a lower rate than other properties, provided that rural lands qualify for one of two types of special appraisal methods. The first type of appraisal is called “Assessments of Lands Designated for Agricultural Use” authorized by Texas Constitution Article VIII, Section 1-d and described in Sections 23.41 through 23.47 of the Texas Tax Code. This type of appraisal is often referred to as 1-d appraisal. The other type of appraisal is called “Taxation of Certain Open Space Land” (OSL) authorized by Texas Constitution Article VIII, Section 1-d-1 and further described in Sections 23.51 through 23.59 of the code, also known as 1-d-1 appraisal. When most people speak in terms of the agricultural use tax valuation for ranches in Texas, they are generally referring to the OSL appraisal method (1-d-1). The Agricultural Use appraisal method (1-d) is appropriate only for lands devoted to full time agricultural operations wherein the owner’s primary occupation and source of income is derived from the agricultural enterprise. -

Integrated Sustainable Wildlife Management Annex 4

Research Institute of Wildlife Ecology Institute of Landscape Development, University of Veterinary Medicine, Recreation and Conservation Planning, Vienna University of Natural Resources and Life Sciences, Vienna ISWIMAN Integrated Sustainable Wildlife Management Principles, Criteria and Indicators for Hunting, Forestry, Agriculture, Recreation Annex 4 PCI-Set for the Interface LEISURE-/ RECREATION MANAGEMENT and Wild Animals / Wildlife Habitats /Hunting Full and Abbreviated Version Friedrich Reimoser, Wolfgang Lexer, Christiane Brandenburg, Richard Zink, Felix Heckl, Andreas Bartel ISBN_Online: 978-3-7001-7216-1 DOI: 10.1553/ISWIMAN-2 Vienna, 2013 (2nd, improved edition) Supported by the Man and Biosphere (MaB) Programme of the Austrian Academy of Sciences PCI-Set for Leisure & Recreation Management considering Wild Animals / Wildlife Habitats / Hunting 2 Preliminary Remarks and Instructions for Use The present Set of Principles, Criteria and Indicators (PCI) refers to the interfaces of sustainable leisure and recreation management and sustainable hunting (focused on the Wienerwald Biosphere Reserve as a case study). It addresses itself to people responsible for planning and managing leisure and recreational activities who in the following will usually be addressed as “leisure and recreation management.” The Assessment Set if for self-evaluation by this target group and is designed to allow for an examination of sustainability of planning and management measures in the fields of leisure and recreational use activities with a view to the lasting conservation of wildlife species and their habitats as well as a sustainable practice of hunting. The purpose is not a general sustainability assessment of leisure and recreation management. The Assessment set is necessary because wild animals, the quality of their habitats and thus also the sustainability of hunting can be considerably influenced by leisure and recreational activities. -

Introduction to Wildlife & Habitat Management

PART I: Introduction INTRODUCTION TO WILDLIFE & HABITAT MANAGEMENT ildlife are the animals that The chapters throughout this bark of young trees and shrubs in live freely in the natural guide will help you to understand fall, winter, and spring when cold Wenvironment. Wild- the relationship between wildlife weather has eliminated green ife includes all and their varied habitats. The leafy food. Food sources available species--game and non- brochures will explain the one year may not be available the game. Songbirds are options available for next. Certain varieties of acorns wildlife. So are snakes, toads, managing your may feed deer, squirrels, and wood butterflies, and fish. These land for ducks but only in those years when wildlife species and numerous garter snake wildlife, and they there is a crop. Planting trees, others provide us with beauty, will offer detailed and specific prac- shrubs, grasses, and flowers and recreation, economic opportunities, tices to help you do it successfully. installing bird feeders are ways that and maintain our quality of life by landowners can help provide food regulating and modifying how our The Components of for wildlife. More than 50 species ecosystems function. Habitat of birds, for example, will eat sun- Habitat can be broken into four flowers. Almost as many kinds of What Is Habitat? parts: food, water, shelter, and birds eat the berries of silky dog- Wildlife needs a place to live. space. When all parts blend togeth- wood. For people, such a place is called er, wildlife not only survives, they "home." For wildlife, the place is thrive. Remove any one of the four Water is needed by every living called "habitat." But wildlife habi- and wildlife must travel to find the thing on earth.