Social and Ecological Benefits of Restored Wolf Populations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wildlife Management in the National Parks

wildlife management IN THE NATIONAL PARKS wildlife management IN IHE NATIONAL PARKS 1969 REPRINT FROM ADMINISTRATIVE POLICIES FOR NATURAL AREAS OF THE NATIONAL PARK SYSTEM U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR • NATIONAL PARK SERVICE For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Washington, D.C. 20402 - Price 15 cents WILDLIFE MANAGEMENT IN THE NATIONAL PARKS ADVISORY BOARD ON WILDLIFE MANAGEMENT, APPOINTED BY SECRETARY OF THE INTERIOR UDALL A. S. Leopold (Chairman), S. A. Cain, C. M. Cottam, I. N. Gabrielson, T. L. Kimball March 4, 1963 Historical In the Congressional Act of 1916 which created the National Park Service, preservation of native animal' life was clearly specified as one of the pur poses of the parks. A frequently quoted passage of the Act states "... which purpose is to conserve the scenery and the natural and historic objects and the wild life therein and to provide for the enjoyment of the same in such manner and by such means as will leave them unimpaired for the enjoy ment of future generations." In implementing this Act, the newly formed Park Service developed a philosophy of wildlife protection, which in that era was indeed the most obvious and immediate need in wildlife conservation. Thus the parks were established as refuges, the animal populations were protected from wildfire. For a time predators were controlled to protect the "good" ani mals from the "bad" ones, but this endeavor mercifully ceased in the 1930's. On the whole, there was little major change in the Park Service practice of wildlife management during the first 40 years of its existence. -

Wolf Hybrids

Wolf Hybrids By Claudine Wilkins and Jessica Rock, Founders of Animal Law Source™ DEFINITION By definition, the wolf-dog hybrid is a cross between a domestic dog (Canis familiaris) and a wild Wolf (Canis Lupus). Wolves are the evolutionary ancestor of dogs. Dogs evolved from wolves through thousands of years of adaptation, living and being selectively bred and domesticated by humans. Because dogs and wolves are evolutionarily connected, dogs and wolves can breed together. Although this cross breeding can occur naturally, it is a rare occurrence in the wild due to the territorial and aggressive nature of wolves. Recently, the breeding of a dog with a wolf has become an accepted new phenomenon because wolf-hybrids are considered to be exotic and prestigious to own. To circumvent the prohibition against keeping wolves as pets, enterprising people have gone underground and are breeding and selling wolf-dog hybrids in their backyards. Consequently, an increase in the number of hybrids are being possessed without the minimum public safeguards required for the common domestic dog. TRAITS OF DOGS AND WOLVES Since wolf hybrids are a genetic mixture of wolves and dogs, they can seem to be similar on the surface. However, even though both may appear to be physically similar, there are many behavioral differences between wolves and dogs. Wolves raised in the wild appear to fear humans and will avoid contact whenever possible. Wolves raised in captivity are not as fearful of humans. This suggests that such fear may be learned rather than inherited. Dogs, on the other hand, socialize quite readily with humans, often preferring human company to that of other dogs. -

After Long-Term Decline, Are Aspen Recovering in Northern Yellowstone? ⇑ Luke E

Forest Ecology and Management 329 (2014) 108–117 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Forest Ecology and Management journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/foreco After long-term decline, are aspen recovering in northern Yellowstone? ⇑ Luke E. Painter a, , Robert L. Beschta a, Eric J. Larsen b, William J. Ripple a a Department of Forest Ecosystems and Society, Oregon State University, Corvallis, OR 97331, USA b Department of Geography and Geology, University of Wisconsin – Stevens Point, Stevens Point, WI 54481-3897, USA article info abstract Article history: In northern Yellowstone National Park, quaking aspen (Populus tremuloides) stands were dying out in the Received 18 December 2013 late 20th century following decades of intensive browsing by Rocky Mountain elk (Cervus elaphus). In Received in revised form 28 May 2014 1995–1996 gray wolves (Canis lupus) were reintroduced, joining bears (Ursus spp.) and cougars (Puma Accepted 30 May 2014 concolor) to complete the guild of large carnivores that prey on elk. This was followed by a marked decline in elk density and change in elk distribution during the years 1997–2012, due in part to increased pre- dation. We hypothesized that these changes would result in less browsing and an increase in height of Keywords: young aspen. In 2012, we sampled 87 randomly selected stands in northern Yellowstone, and compared Wolves our data to baseline measurements from 1997 and 1998. Browsing rates (the percentage of leaders Elk Browsing effects browsed annually) in 1997–1998 were consistently high, averaging 88%, and only 1% of young aspen Trophic cascade in sample plots were taller than 100 cm; none were taller than 200 cm. -

Wolf Interactions with Non-Prey

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln USGS Northern Prairie Wildlife Research Center US Geological Survey 2003 Wolf Interactions with Non-prey Warren B. Ballard Texas Tech University Ludwig N. Carbyn Canadian Wildlife Service Douglas W. Smith US Park Service Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/usgsnpwrc Part of the Animal Sciences Commons, Behavior and Ethology Commons, Biodiversity Commons, Environmental Policy Commons, Recreation, Parks and Tourism Administration Commons, and the Terrestrial and Aquatic Ecology Commons Ballard, Warren B.; Carbyn, Ludwig N.; and Smith, Douglas W., "Wolf Interactions with Non-prey" (2003). USGS Northern Prairie Wildlife Research Center. 325. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/usgsnpwrc/325 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the US Geological Survey at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in USGS Northern Prairie Wildlife Research Center by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. 10 Wolf Interactions with Non-prey Warren B. Ballard, Ludwig N. Carbyn, and Douglas W. Smith WOLVES SHARE THEIR ENVIRONMENT with many an wolves and non-prey species. The inherent genetic, be imals besides those that they prey on, and the nature of havioral, and morphological flexibility of wolves has the interactions between wolves and these other crea allowed them to adapt to a wide range of habitats and tures varies considerably. Some of these sympatric ani environmental conditions in Europe, Asia, and North mals are fellow canids such as foxes, coyotes, and jackals. America. Therefore, the role of wolves varies consider Others are large carnivores such as bears and cougars. -

Effects of Wolf Reintroduction on Coyote Temporal Activity

Background Information and Study Design: Motivation: Effects of Wolf We will conduct an observational study in Montana, Wisconsin, and Maine, which are spread out over the U.S. - In each of these states we will have ● After wolves (Canis lupus) were driven to extinction in Reintroduction three control groups and three experimental groups where we study the the United States, coyotes (Canis latrans) expanded temporal activity of both wolves and coyotes. into niches previously occupied by wolves. on Coyote As a control group, we will study areas where coyotes live, but wolves have ● 1990’s - efforts were made to reintroduce wolves; led yet to be reintroduced. to successful re-establishment of several wolf packs Temporal Activity We plan on monitoring temporal activity through the use of radio collars to and a return to their status as the dominant predator By Tessa Garufi, Lily Grady, and track coyote movement. If movement is occurring primarily at night with no ● In areas where wolves and coyotes now coexist, Libby Boulanger motion during the day, it can be reasoned that the coyotes in the area are coyotes experience increased pressure - they have to primarily nocturnal and if movement is during the day with no motion at night, contend with the risk of wolf-caused mortalities and it can be reasoned that they are primarily diurnal. Wolf temporal activity will resource competition against a more dominant also be monitored to determine how different the activity timing of wolves and predator. coyotes are in areas where they coexist. ● We want to determine if coyotes living in the same area as wolves have experienced a temporal niche Intended Analysis shift as a response to the increased pressure - if a Because our independent variable is categorical with two groups shift has occurred, it could lead to an increase in (wolves present or wolves absent) and our response variable is potentially harmful coyote-human interactions. -

Red Wolf Brochure

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Endangered Red Wolves The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service is reintroducing red wolves to prevent extinction of the species and to restore the ecosystems in which red wolves once occurred, as mandated by the Endangered Species Act of 1973. According to the Act, endangered and threatened species are of aesthetic, ecological, educational, historical, recreational, and scientific value to the nation and its people. On the Edge of Extinction The red wolf historically roamed as a top predator throughout the southeastern U.S. but today is one of the most endangered animals in the world. Aggressive predator control programs and clearing of forested habitat combined to cause impacts that brought the red wolf to the brink of extinction. By 1970, the entire population of red wolves was believed to be fewer than 100 animals confined to a small area of coastal Texas and Louisiana. In 1980, the red wolf was officially declared extinct in the wild, while only a small number of red wolves remained in captivity. During the 1970’s, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service established criteria which helped distinguish the red wolf species from other canids. From 1974 to 1980, the Service applied these criteria to find that only 17 red wolves were still living. Based on additional Greg Koch breeding studies, only 14 of these wolves were selected as founders to begin the red wolf captive breeding population. The captive breeding program is coordinated for the Service by the Point Defiance Zoo & Aquarium in Tacoma, Washington, with goals of conserving red wolf genetic diversity and providing red wolves for restoration to the wild. -

Wolf Family Values

Wolf family values The exquisitely balanced social life of the wolf has implications far beyond the pack, says Sharon Levy ORDON HABER was tracking a wolf pack Wolf Project. Despite many thousands of he had known for over 40 years when his hours spent in the field, Haber published G plane crashed on a remote stretch of the little peer-reviewed documentation of his Toklat river in Denali national park, Alaska, work. Now, however, in the months following last October. The fatal accident silenced one his sudden death, Smith and other wolf of the most outspoken and controversial biologists have reported findings that support advocates for wolf protection. Haber, an some of Haber’s ideas. independent biologist, had spent a lifetime Once upon a time, folklore shaped our studying the behaviour and ecology of wolves thinking about wolves. It is only in the past and his passion for the animals was obvious. two decades that biologists have started to “I am still in awe of what I see out there,” he build a clearer picture of wolf ecology (see wrote on his website. “Wolves enliven the “Beyond myth and legend”, page 42). Instead northern mountains, forests, and tundra like of seeing rogue man-eaters and savage packs, no other creature, helping to enrich our stay we now understand that wolves have evolved on the planet simply by their presence as other to live in extended family groups that include Few places remain highly advanced societies in our midst.” a breeding pair – typically two strong, where wolves can live His opposition to hunting was equally experienced individuals – along with several as nature intended intense. -

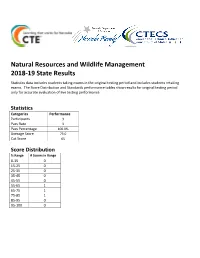

Natural Resources and Wildlife Management Statistics

Natural Resources and Wildlife Management 2018-19 State Results Statistics data includes students taking exams in the original testing period and includes students retaking exams. The Score Distribution and Standards performance tables show results for original testing period only for accurate evaluation of live testing performance. Statistics Categories Performance Participants 3 Pass Rate 3 Pass Percentage 100.0% Average Score 73.0 Cut Score 65 Score Distribution % Range # Scores in Range 0-15 0 15-25 0 25-35 0 35-45 0 45-55 0 55-65 1 65-75 1 75-85 1 85-95 0 95-100 0 Natural Resources and Wildlife Management 1) CONTENT STANDARD 1.0: EXPLORE NATURAL RESOURCE SCIENCE AND MANAGEMENT 75.93% 1) Performance Standard 1.1 : Investigate the Relationship Between Natural Resources and Society, Including Conflict Management 72.22% 1) 1.1.1 Define natural resource management 77.78% 3) 1.1.3 Describe human dependency and demands on natural resources 88.89% 4) 1.1.4 Explain natural resource conservation 66.67% 5) 1.1.5 Investigate the effects of multiple uses of natural resources (e.g., recreation, mining, agriculture, forestry, public lands grazing, etc.) 66.67% 6) 1.1.6 Analyze societal issues related to natural resource management 50% 2) Performance Standard 1.2 : Explain Interrelationships Between Natural Resources and Humans in Managing Natural Environments 86.67% 1) 1.2.1 Explain the effects and/or trade-off of population growth, greater energy consumption, and increased technology and development on natural resources and the environment 83.33% -

Glimpse of an African… Wolf? Cécile Bloch

$6.95 Glimpse of an African… Wolf ? PAGE 4 Saving the Red Wolf Through Partnerships PAGE 9 Are Gray Wolves Still Endangered? PAGE 14 Make Your Home Howl Members Save 10% Order today at shop.wolf.org or call 1-800-ELY-WOLF Your purchases help support the mission of the International Wolf Center. VOLUME 25, NO. 1 THE QUARTERLY PUBLICATION OF THE INTERNATIONAL WOLF CENTER SPRING 2015 4 Cécile Bloch 9 Jeremy Hooper 14 Don Gossett In the Long Shadow of The Red Wolf Species Survival Are Gray Wolves Still the Pyramids and Beyond: Plan: Saving the Red Wolf Endangered? Glimpse of an African…Wolf? Through Partnerships In December a federal judge ruled Geneticists have found that some In 1967 the number of red wolves that protections be reinstated for of Africa’s golden jackals are was rapidly declining, forcing those gray wolves in the Great Lakes members of the gray wolf lineage. remaining to breed with the more wolf population area, reversing Biologists are now asking: how abundant coyote or not to breed at all. the USFWS’s 2011 delisting many golden jackals across Africa The rate of hybridization between the decision that allowed states to are a subspecies known as the two species left little time to prevent manage wolves and implement African wolf? Are Africa’s golden red wolf genes from being completely harvest programs for recreational jackals, in fact, wolves? absorbed into the expanding coyote purposes. If biological security is population. The Red Wolf Recovery by Cheryl Lyn Dybas apparently not enough rationale for Program, working with many other conservation of the species, then the organizations, has created awareness challenge arises to properly express and laid a foundation for the future to the ecological value of the species. -

For-74: a Guide to Urban Habitat Conservation Planning

FOR-74 A Guide to Urban Habitat Conservation Planning Thomas G. Barnes, Extension Wildlife Specialist Lowell Adams, National Institute for Urban Wildlife entuckians value their forests and Kother natural resources for aes- Guidelines for Considering Wildlife in the Urban Development thetic, recreational, and economic Process significance, so over the past several Promote habitats that will have the food, cover, water, and living space that decades they have become increasingly all wildlife require by following these guidelines: concerned about the loss of wildlife • Before development, maximize open space and make an effort to protect the habitat and greenspace. Urban and most valuable wildlife habitat by placing buildings on less important portions suburban development is one of the of the site. Choosing cluster development, which is flexible, can help. leading causes of this loss: A recent • Provide water, and design stormwater control impoundments to benefit wildlife. study indicated that every day in • Use native plants that have value for wildlife as well as aesthetic appeal. Kentucky more than 100 acres of rural • Provide bird-feeding stations and nest boxes for cavity-nesting birds like land is being converted to urban house wrens and wood ducks. development. • Educate residents about wildlife conservation, using, for example, informa- Because concern for loss of tion packets or a nature trail through open space. greenspace is not new, we have for • Ensure a commitment to managing urban wildlife habitats. some time created attractive urban greenspace environments with our parks and backyards. These The publication can also be useful to A landscape is a large area com- greenspaces have been created not so the average homeowner in understand- posed of ecosystems (the plants, much for wildlife habitats as for people ing the complex issues involved in animals, other living organisms, and to enjoy, but the potential for wildlife landscape planning and wildlife their physical surroundings). -

Oregon Wolf Conservation and Management 2020 Annual Report

Oregon Wolf Conservation and Management 2020 Annual Report This report to the Oregon Fish and Wildlife Commission presents information on the status, distribution, and management of wolves in the State of Oregon from January 1, 2020 to December 31, 2020. Suggested Citation: Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife. 2021. Oregon Wolf Conservation and Management 2020 Annual Report. Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife, 4034 Fairview Industrial Drive SE. Salem, OR, 97302 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ...................................................................................................................... 2 OREGON WOLF PROGRAM OVERVIEW .......................................................................................... 3 Regulatory Status .................................................................................................................................. 3 Minimum Numbers, Reproduction, and Distribution ........................................................................... 4 Monitoring ............................................................................................................................................ 6 Information and Outreach ..................................................................................................................... 7 Wolf Program Funding ......................................................................................................................... 8 LIVESTOCK DEPREDATION MANAGEMENT ................................................................................ -

Ecology of the European Badger (Meles Meles) in the Western Carpathian Mountains: a Review

Wildl. Biol. Pract., 2016 Aug 12(3): 36-50 doi:10.2461/wbp.2016.eb.4 REVIEW Ecology of the European Badger (Meles meles) in the Western Carpathian Mountains: A Review R.W. Mysłajek1,*, S. Nowak2, A. Rożen3, K. Kurek2, M. Figura2 & B. Jędrzejewska4 1 Institute of Genetics and Biotechnology, Faculty of Biology, University of Warsaw, Pawińskiego 5a, 02-106 Warszawa, Poland. 2 Association for Nature “Wolf”, Twardorzeczka 229, 34-324 Lipowa, Poland. 3 Institute of Environmental Sciences, Jagiellonian University, Gronostajowa 7, 30-387 Kraków, Poland. 4 Mammal Research Institute, Polish Academy of Sciences, Waszkiewicza 1c, 17-230 Białowieża, Poland. * Corresponding author email: [email protected]. Keywords Abstract Altitudinal Gradient; This article summarizes the results of studies on the ecology of the European Diet Composition; badger (Meles meles) conducted in the Western Carpathians (S Poland) Meles meles; from 2002 to 2010. Badgers inhabiting the Carpathians use excavated setts Mustelidae; (53%), caves and rock crevices (43%), and burrows under human-made Sett Utilization; constructions (4%) as permanent shelters. Excavated setts are located up Spatial Organization. to 640 m a.s.l., but shelters in caves and crevices can be found as high as 1,050 m a.s.l. Badger setts are mostly located on slopes with southern, eastern or western exposure. Within their territories, ranging from 3.35 to 8.45 km2 (MCP100%), badgers may possess 1-12 setts. Family groups are small (mean = 2.3 badgers), population density is low (2.2 badgers/10 km2), as is reproduction (0.57 young/year/10 km2). Hunting by humans is the main mortality factor (0.37 badger/year/10 km2).