For-74: a Guide to Urban Habitat Conservation Planning

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wildlife Management in the National Parks

wildlife management IN THE NATIONAL PARKS wildlife management IN IHE NATIONAL PARKS 1969 REPRINT FROM ADMINISTRATIVE POLICIES FOR NATURAL AREAS OF THE NATIONAL PARK SYSTEM U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR • NATIONAL PARK SERVICE For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Washington, D.C. 20402 - Price 15 cents WILDLIFE MANAGEMENT IN THE NATIONAL PARKS ADVISORY BOARD ON WILDLIFE MANAGEMENT, APPOINTED BY SECRETARY OF THE INTERIOR UDALL A. S. Leopold (Chairman), S. A. Cain, C. M. Cottam, I. N. Gabrielson, T. L. Kimball March 4, 1963 Historical In the Congressional Act of 1916 which created the National Park Service, preservation of native animal' life was clearly specified as one of the pur poses of the parks. A frequently quoted passage of the Act states "... which purpose is to conserve the scenery and the natural and historic objects and the wild life therein and to provide for the enjoyment of the same in such manner and by such means as will leave them unimpaired for the enjoy ment of future generations." In implementing this Act, the newly formed Park Service developed a philosophy of wildlife protection, which in that era was indeed the most obvious and immediate need in wildlife conservation. Thus the parks were established as refuges, the animal populations were protected from wildfire. For a time predators were controlled to protect the "good" ani mals from the "bad" ones, but this endeavor mercifully ceased in the 1930's. On the whole, there was little major change in the Park Service practice of wildlife management during the first 40 years of its existence. -

Marine Director WCS Finaltor

JOB DESCRIPTION Director, Marine Conservation and Fisheries Wildlife Conservation Society Founded in 1895 as the New York Zoological Society The Wildlife Conservation Society seeks a Director of Marine Conservation and Fisheries, to be based at WCS headquarters in New York City. WCS has a long history of ocean exploration and conservation, including William Beebe’s 1934 record-setting bathysphere dive and Roger Payne’s extraordinary 1974 discovery of humpback whale songs. From these early roots, and reflecting the WCS focus on saving wildlife and wild places, WCS’ marine conservation efforts currently focus on four strategies: Marine Protected Areas, sustainable fisheries, marine mammals, and sharks and rays. Supporting these strategies, WCS maintains a strong commitment to applied marine scientific research and is building its capacity to leverage our impact through WCS’ New York Aquarium and other innovative partnerships. To deliver on these objectives at scale the Director oversees all WCS marine conservation efforts, including the implementation of marine conservation actions by ~250 marine conservation staff in Belize, Cuba, Nicaragua, Argentina, Chile, Gabon, Congo, Equatorial Guinea, Kenya, Tanzania, Mozambiue, Madagascar, Bangladesh, Myanmar, Indonesia, Papua New Guinea, Solomon Islands, Vanuatu, Fiji, New York and the Arctic Beringia, as well as overseeing staff who coordinate global initiatives on marine species (cetaceans and sharks), climate, fisheries and marine policy. The program is staffed by a dynamic and committed team of field scientists based at sites around the world, and a directorate of six staff in New York. Position Objectives: * Direct WCS’s marine conservation programs across 9 global priority regions and all 5 oceans in Africa, Asia, Latin America and North America that largely focus on the establishment and management of marine protected areas, artisanal, and commercial fisheries, and the global conservation of marine mammals and sharks and rays. -

Hudson River Estuary Wildlife and Habitat Conservation Framework

PART I: An Approach to Biodiversity Conservation Introduction The Hudson River Valley is one of New York State’s most impressive regions, rich in history, and cultural, geological, and biological diversity (Figure 1). At the heart of this region is the Hudson River Estuary, which ranges from saline to fresh water, and pulses daily with four-foot ocean tides. The Hudson River Estuary corridor is one of the most densely populated areas of the country and has long been the fastest growing region of the state. Additionally, it is one of the state’s primary industrial centers. As a result, tremendous pressures have been placed on the health and sustainability of the region’s natural resources. Despite these stresses, it remains highly productive with thousands of species of plants and animals. Because of the diversity and complexity of both the biological resources and the threats that face these resources, partnerships involving landowners, municipalities, non-profit organizations, government agencies, and others must be developed to effectively con- serve biodiversity in the Hudson River Valley. Successful implementation of the strate- gies and actions presented in this report will require a commitment to both developing and sustaining these partnerships. The Hudson River Estuary Biodiversity Program The purpose of the Hudson River Estuary Biodiversity Program is to support the conser- vation, recovery, and sustainable use of the biodiversity of the Hudson River Estuary cor- ridor, especially as it relates to terrestrial ecosystems. The project emphasizes voluntary approaches to biodiversity conservation in the context of local home rule. The broad goals of the program are: 1. -

Reforming Section 10 and the Habitat Conservation Plan Program David A

Northwestern University School of Law Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons Faculty Working Papers 2009 Reforming Section 10 and the Habitat Conservation Plan Program David A. Dana Northwestern University School of Law, [email protected] Repository Citation Dana, David A., "Reforming Section 10 and the Habitat Conservation Plan Program" (2009). Faculty Working Papers. Paper 193. http://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/facultyworkingpapers/193 This Working Paper is brought to you for free and open access by Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Working Papers by an authorized administrator of Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. DRAFT Reforming Section 10 and the Habitat Conservation Program David A. Dana Northwestern University One of the central dilemmas of the Endangered Species Act is how to foster species conservation and recovery on private land. Much of the habitat thought to be occupied by endangered species is on private land. According to some estimates, more than two thirds of listed endangered species can be found on private land.1 And even in areas where there is substantial federal land that contains critical habitat, the federal land often is part of a patchwork of federal, state, local and purely private holdings. (Importantly, the Act treats state and locally-owned land as private land.) In such cases, any comprehensive recovery plan would need to extend to private land. In theory, the Endangered Species Act powerfully addresses the risks posed to endangered species by private development and other economic activity on private land. Section Nine of the Act prohibits the "taking" of endangered species on private land, and broadly defines "take."2 The Fish and Wildlife Service's regulation implementing Section 9 clearly encompass private development activity that kills or prevents the reproduction of protected species members,3 and the United States Supreme Court upheld 4 that regulation in Sweet Home v. -

Socioeconomic Benefits of Habitat Restoration

Socioeconomic Benefits of Habitat Restoration U.S. Department of Commerce National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration National Marine Fisheries Service NOAA Technical Memorandum NMFS-OHC-1 May 2017 Socioeconomic Benefits of Habitat Restoration Giselle Samonte1, Peter Edwards2, Julia Royster3, Victoria Ramenzoni4, and Summer Morlock5 1 Contractor with Earth Resources Technology, Inc. NOAA Fisheries Office of Habitat Conservation 1315 East-West Hwy, Silver Spring, MD 20910 2 Contractor with The Baldwin Group, Inc. NOAA National Ocean Service, Office for Coastal Management 1305 East-West Highway, Silver Spring, MD 20910 3 NOAA Fisheries Office of Habitat Conservation 1315 East West Highway, Silver Spring, MD 20910. 4 Harte Research Institute for Gulf of Mexico Studies Texas A&M University-Corpus Christi 6300 Ocean Drive, Corpus Christi, TX 78412 5 NOAA Budget Office, Department of Commerce 1401 Constitution Ave. NW, Washington D.C. 20230 NOAA Technical Memorandum NMFS-OHC-1 May 2017 U.S. Department of Commerce Wilbur L. Ross, Jr., Secretary National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Benjamin Friedman, Acting NOAA Administrator National Marine Fisheries Service Chris Oliver, Assistant Administrator for Fisheries Recommended citation: Giselle Samonte, Peter Edwards, Julia Royster, Victoria Ramenzoni, and Summer Morlock. 2017. Socioeconomic Benefits of Habitat Restoration. NOAA Tech. Memo. NMFS-OHC-1, 66 p. Copies of this report may be obtained from: Office of Habitat Conservation National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration 1315 -

An Economic Analysis of the Benefits of Habitat Conservation on California Rangelands

An Economic Analysis of the Benefits of Habitat Conservation on California Rangelands CONSERVATION ECONOMICS WHITE PAPER Conservation Economics Program Timm Kroeger, Ph.D., Frank Casey, Ph.D., Pelayo Alvarez, Ph.D., Molly Cheatum and Lily Tavassoli Defenders of Wildlife March 2010 i This study can be found online at http://www.defenders.org/programs_and_policy/science_and_economics/conservation_ec onomics/valuation/index.php Suggested citation: Kroeger, T., F. Casey, P. Alvarez, M. Cheatum and L. Tavassoli. 2009. An Economic Analysis of the Benefits of Habitat Conservation on California Rangelands. Conservation Economics White Paper. Conservation Economics Program. Washington, DC: Defenders of Wildlife. 91 pp. Authors: Timm Kroeger, Ph.D., Natural Resources Economist, Conservation Economics Program; Frank Casey, Ph.D., Director, Conservation Economics Program; Pelayo Alvarez, Ph.D., Conservation Program Director, California Rangeland Conservation Coalition; Molly Cheatum, Conservation Economics Associate, Conservation Economics Program; Lily Tavassoli, Intern, Conservation Economics Program. Cover photo credits clockwise from top: U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Natural Resources Conservation Service Natural Resources Conservation Service California Cattlemen’s Association Defenders of Wildlife is a national nonprofit membership organization dedicated to the protection of all native wild animals and plants in their natural communities. National Headquarters Defenders of Wildlife 1130 17th St. NW Washington, DC 20036 USA Tel.: (202) -

Chapter 4 Natural Resources and Environmental Constraints

Chapter 4 Natural Resources and Environmental Constraints PERSONAL VISION STATEMENTS “I want to live in a city that cares about air quality and the environment.” “Keep Birmingham beautiful, especially the water ways.” 4.1 CITY OF BIRMINGHAM COMPREHENSIVE PLAN PART II | CHAPTER 4 NATURAL RESOURCES AND ENVIRONMENTAL CONSTRAINTS GOALS POLICIES FOR DECISION MAKERS natural areas and conservation A comprehensive green infrastructure • Support the creation of an interconnected green infrastructure network that includes system provides access to and natural areas for passive recreation, stormwater management, and wildlife habitat. preserves natural areas and • Consider incentives for the conservation and enhancement of natural and urban environmentally sensitive areas. forests. Reinvestment in existing communities • Consider incentives for reinvestment in existing communities rather than conserves resources and sensitive “greenfields,” for new commercial, residential and institutional development. environments. • Consider incentives for development patterns and site design methods that help protect water quality, sensitive environmental features, and wildlife habitat. air and water quality The City makes every effort to • Support the development of cost-effective multimodal transportation systems that consistently meet clean air standards. reduce vehicle emissions. • Encourage use of clean fuels and emissions testing. • Emphasize recruitment of clean industry. • Consider incentives for industries to reduce emissions over time. • Promote the use of cost-effective energy efficient design, materials and equipment in existing and private development. The City makes every effort to • Encourage the Birmingham Water Works Board to protect water-supply sources consistently meet clean water located outside of the city to the extent possible. standards. • Consider incentives for development that protects the city’s water resources. -

Habitat Conservation, Biodiversity and Wildlife Natural History in Northwestern Amazonia

HABITAT CONSERVATION, BIODIVERSITY AND WILDLIFE NATURAL HISTORY IN NORTHWESTERN AMAZONIA Daniel M. Brooks Houston Museum of Natural Science; Dept. of Vertebrate Zoology; One Hermann Circle Dr.; Houston, Texas 77030-1799 – [email protected] The Ecuadorian Schuar, Colombian Tikuna and Venezuelan Piaroa inhabit northwestern Amazonia. The interactions of these tribes with wildlife is quite complex, taking place for hundreds of years prior to the Spanish invasion some 500 years ago. For example, these tribes not only utilize “bushmeat” of many large mammals and gamebirds as a major protein source (Brooks 1999), but also utilize the feathers of certain species of Amazonian birds for ornamentation. While many of the tribes use feathers from various species, the main species that feathers are used (in descending order) are from Macaws (Ara ) and Amazon parrots ( Amazona ), Great Egrets ( Casmerodius ), Curassows ( Crax and Mitu ), Toucans ( Ramphastos ) and various members of the family Contingidae; in some cases mammal remains are used to, such Tamarin ( Saguinus ) tails (Brooks unpubl. data). Unfortunately, many of these species are threatened by forest destruction and over- hunting in the case of Curassows (Brooks and Strahl 1997). In this note I generally describe habitat and current levels of forest destruction in northwestern Amazonia, as well as biodiversity and natural history of some of the species utilized by Schuar, Tikuna and Piaroa. Habitat description and forest destruction in northwestern Amazonia Average annual temperature in northwestern Amazonia is 26 Celcius, and annual rainfall exceeds 2500 millimeters (Gorchov et al. 1995). Whereas most temperate regions experience several seasons, the Amazon experiences two subtle contrasts over the year in water level: high water season occurs November – May, and low water occurs June – October (Brooks 1998). -

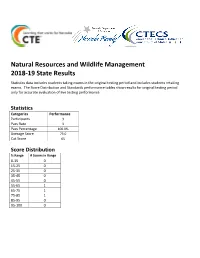

Natural Resources and Wildlife Management Statistics

Natural Resources and Wildlife Management 2018-19 State Results Statistics data includes students taking exams in the original testing period and includes students retaking exams. The Score Distribution and Standards performance tables show results for original testing period only for accurate evaluation of live testing performance. Statistics Categories Performance Participants 3 Pass Rate 3 Pass Percentage 100.0% Average Score 73.0 Cut Score 65 Score Distribution % Range # Scores in Range 0-15 0 15-25 0 25-35 0 35-45 0 45-55 0 55-65 1 65-75 1 75-85 1 85-95 0 95-100 0 Natural Resources and Wildlife Management 1) CONTENT STANDARD 1.0: EXPLORE NATURAL RESOURCE SCIENCE AND MANAGEMENT 75.93% 1) Performance Standard 1.1 : Investigate the Relationship Between Natural Resources and Society, Including Conflict Management 72.22% 1) 1.1.1 Define natural resource management 77.78% 3) 1.1.3 Describe human dependency and demands on natural resources 88.89% 4) 1.1.4 Explain natural resource conservation 66.67% 5) 1.1.5 Investigate the effects of multiple uses of natural resources (e.g., recreation, mining, agriculture, forestry, public lands grazing, etc.) 66.67% 6) 1.1.6 Analyze societal issues related to natural resource management 50% 2) Performance Standard 1.2 : Explain Interrelationships Between Natural Resources and Humans in Managing Natural Environments 86.67% 1) 1.2.1 Explain the effects and/or trade-off of population growth, greater energy consumption, and increased technology and development on natural resources and the environment 83.33% -

Landowner Guide to the Wildlife Habitat Conservation and Management Program

Landowner Guide to the Wildlife Habitat Conservation and Management Program This document provides an overview of the Wildlife Habitat Conservation and Management Program, administered by the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife (ODFW), and the expectations of the program for interested landowners. ODFW recommends that interested landowners first read this Guide, and if eligible, contact the local ODFW biologists for more information. Additional resources are available on the following website: http://www.dfw.state.or.us/lands/whcmp/. Table of Contents: A. Purpose of the habitat program B. Objective of the habitat program C. History of the habitat program D. Calculating a property’s assessed value E. Dwellings and homesites F. Participating Counties G. Moving from one special assessment category to another H. Landowner process to participate in the program I. Information needed in a habitat plan J. Conservation and management actions in a habitat plan K. Resources counties and cities can provide to assist landowners L. Submission of a habitat plan for review M. Implementation of approved WHCMP plans N. Application for wildlife habitat special assessment O. Monitoring by ODFW P. Amending an approved habitat plan Q. Change of ownership R. Disqualification of a property from wildlife habitat special assessment S. Appendix a. Certification of Eligibility Form b. Landowner Interest Form c. Annual Status Report Form p. 1 2015 A. Purpose of the habitat program: Provide an incentive for habitat conservation The Wildlife Habitat Conservation and Management Program (habitat program), administered by the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife (ODFW), is a cooperative effort involving state and local governments and other partners to help private landowners voluntarily conserve native wildlife habitat. -

AREI Chapter 3.3 Wildlife Resources Conservation

3.3 Wildlife Resources Conservation U.S. agriculture is well positioned to play a major role in protecting and enhancing the nation's wildlife. Wildlife in the U.S is dependent on the considerable land and water resources under the control of agriculture. At the same time, agriculture is one of the most competitive sectors in the U.S., and economic tradeoffs can make it difficult for farmers, on their own, to support wildlife conservation efforts requiring them to adopt more wildlife-friendly production techniques or directly allocate additional land and water resources to wildlife. Besides the opportunity costs associated with shifting resource use or changing production techniques, the public goods and common property nature of wildlife can also affect a farmers decision to protect wildlife found on their land. However, the experiences of USDA conservation programs demonstrate that farmers are willing to voluntarily shift additional land and water resources into habitat, provided they are compensated. Contents Page Introduction....................................................................................................................................................... 1 Tradeoffs Between Agricultural Production and Wildlife Habitat ................................................................... 2 Asymmetric distribution of costs and benefits....................................................................................... 2 Ownership of land and water resources .............................................................................................. -

Water Management Companion Plan

WATER MANAGEMENT COMPANION PLAN December 2016 Photo Credit: Left: Lake Shasta, California Date: 19 July 2010 Photographer: brianscotland0 via pixabay Right: Monarch Butterfly Date: 17 March 2006 Photographer: Armon via Wiki Commons Prepared by Blue Earth Consultants, LLC December 2016 Disclaimer: Although we have made every effort to ensure that the information contained in this report accurately reflects SWAP 2015 companion plan development team discussions shared through web-based platforms, e-mails, and phone calls, Blue Earth Consultants, LLC makes no guarantee of the completeness and accuracy of information provided by all project sources. SWAP 2015 and associated companion plans are non-regulatory documents. The information shared is not legally binding nor does it reflect a change in the laws guiding wildlife and ecosystem conservation in the state. In addition, mention of organizations or entities in this report as potential partners does not indicate a willingness and/or commitment on behalf of these organizations or entities to partner, fund, or provide support for implementation of this plan or SWAP 2015. The consultant team developed companion plans for multiple audiences, both with and without jurisdictional authority for implementing strategies and conservation activities described in SWAP 2015 and associated companion plans. These audiences include but are not limited to the California Department of Fish and Wildlife leadership team and staff; the California Fish and Game Commission; cooperating state, federal, and local government agencies and organizations; California Tribes and tribal governments; and various partners (such as non-governmental organizations, academic research institutions, and citizen scientists). Table of Contents Acronyms and Abbreviations ................................................................................................ iii 1.