Upper Green River Basin Ecosystem Services Feasibility Analysis Project Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wildlife Management in the National Parks

wildlife management IN THE NATIONAL PARKS wildlife management IN IHE NATIONAL PARKS 1969 REPRINT FROM ADMINISTRATIVE POLICIES FOR NATURAL AREAS OF THE NATIONAL PARK SYSTEM U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR • NATIONAL PARK SERVICE For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Washington, D.C. 20402 - Price 15 cents WILDLIFE MANAGEMENT IN THE NATIONAL PARKS ADVISORY BOARD ON WILDLIFE MANAGEMENT, APPOINTED BY SECRETARY OF THE INTERIOR UDALL A. S. Leopold (Chairman), S. A. Cain, C. M. Cottam, I. N. Gabrielson, T. L. Kimball March 4, 1963 Historical In the Congressional Act of 1916 which created the National Park Service, preservation of native animal' life was clearly specified as one of the pur poses of the parks. A frequently quoted passage of the Act states "... which purpose is to conserve the scenery and the natural and historic objects and the wild life therein and to provide for the enjoyment of the same in such manner and by such means as will leave them unimpaired for the enjoy ment of future generations." In implementing this Act, the newly formed Park Service developed a philosophy of wildlife protection, which in that era was indeed the most obvious and immediate need in wildlife conservation. Thus the parks were established as refuges, the animal populations were protected from wildfire. For a time predators were controlled to protect the "good" ani mals from the "bad" ones, but this endeavor mercifully ceased in the 1930's. On the whole, there was little major change in the Park Service practice of wildlife management during the first 40 years of its existence. -

BIG RIVER ECOSYSTEM: Program 2

BIG RIVER ECOSYSTEM: A Question of Net Worth PURPOSE To explore biodiversity at the ecosystem level. KERA CONNECTIONS to Life Science Program 2 Core Content: Structure and Function in Living Systems Academic Expectations: 2.2 Patterns, 2.3 Systems, 2.4 Models & Scale ANSWERS TO Process Skills: Observation, Modeling aFIELD NOTES OBJECTIVES 1. In a hot and hostile environment, Students should be able to: the evaporated water cannot be 1.identify five “big river” organisms incorporated into living cells (as 2.construct a diagram showing interactions between living and we know them). nonliving parts of an ecosystem 2. An extremely cold environment, 3. discuss factors that affect the level of biodiversity in their river basin. or frozen desert, does not allow cells to utilize water. VOCABULARY 3. Answers will vary but should Teachers may wish to discuss the following terms: display logical flow of water and aquatic, commercial, ecosystem, water cycle and watershed. allow for recirculation in a loop. 4. Arteries and veins. aFIELD NOTEBOOK 5. A pumping heart. Ideas for Teachers 6. Diagram A shows many different A. Develop a concept map for the water cycle. Include these items in types of ecosystems in close the concept map: clouds, groundwater, apple tree, stream, precipita- proximity. tion, condensation, evaporation, harvest mouse, snowflakes, sun and 7. Add a watering hole, plant a humans. What other cycles are needed to maintain an ecosystem? miniature forest, create a B. Biospheres, containing algae, brine shrimp and water, are often meadow of wildflowers. Most shown in advertisements. Analyze how the biosphere is self-main- importantly, break up a monocul- taining. -

Lesson 4: Sediment Deposition and River Structures

LESSON 4: SEDIMENT DEPOSITION AND RIVER STRUCTURES ESSENTIAL QUESTION: What combination of factors both natural and manmade is necessary for healthy river restoration and how does this enhance the sustainability of natural and human communities? GUIDING QUESTION: As rivers age and slow they deposit sediment and form sediment structures, how are sediments and sediment structures important to the river ecosystem? OVERVIEW: The focus of this lesson is the deposition and erosional effects of slow-moving water in low gradient areas. These “mature rivers” with decreasing gradient result in the settling and deposition of sediments and the formation sediment structures. The river’s fast-flowing zone, the thalweg, causes erosion of the river banks forming cliffs called cut-banks. On slower inside turns, sediment is deposited as point-bars. Where the gradient is particularly level, the river will branch into many separate channels that weave in and out, leaving gravel bar islands. Where two meanders meet, the river will straighten, leaving oxbow lakes in the former meander bends. TIME: One class period MATERIALS: . Lesson 4- Sediment Deposition and River Structures.pptx . Lesson 4a- Sediment Deposition and River Structures.pdf . StreamTable.pptx . StreamTable.pdf . Mass Wasting and Flash Floods.pptx . Mass Wasting and Flash Floods.pdf . Stream Table . Sand . Reflection Journal Pages (printable handout) . Vocabulary Notes (printable handout) PROCEDURE: 1. Review Essential Question and introduce Guiding Question. 2. Hand out first Reflection Journal page and have students take a minute to consider and respond to the questions then discuss responses and questions generated. 3. Handout and go over the Vocabulary Notes. Students will define the vocabulary words as they watch the PowerPoint Lesson. -

IUCN World Conservation Congress

S IUCN Resolutions, Recommendations and other Decisions World Conservation Congress Honolulu, Hawai‘i, United States of America 6 –10 September 2016 IUCN Resolutions, Recommendations and other Decisions World Conservation Congress Honolulu, Hawai‘i, United States of America 6–10 September 2016 The designation of geographical entities in this book, and the presentation of the material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of IUCN concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect those of IUCN. Published by: IUCN, Gland, Switzerland Copyright: © 2016 International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources Reproduction of this publication for educational or other non-commercial purposes is authorised without prior written permission from the copyright holder provided the source is fully acknowledged. Reproduction of this publication for resale or other commercial purposes is prohibited without prior written permission of the copyright holder. Citation: IUCN (2016). IUCN Resolutions, Recommendations and other Decisions. Gland, Switzerland: IUCN. 106pp. Produced by: IUCN Publications Unit Available for download from: www.iucn.org/resources/publications Contents Foreword 5 Acknowledgements 8 Table of Resolutions, Recommendations and other Decisions 10 Resolutions 17 Recommendations 216 Other Decisions 244 Annex 1 – Explanation of votes 248 Annex 2 – Statement of the United States Government on the IUCN Motions Process 297 3 Foreword It is with great pleasure that the Resolutions Committee hereby forwards to IUCN Members, Commission members, IUCN Secretariat staff, other Congress participants and all interested parties, the Resolutions and Recommendations as well as other key decisions adopted by the Members’ Assembly at the World Conservation Congress held in Hawai‘i, United States of America, 1–10 September 2016. -

Paseo De Las Iglesias Santa Cruz River Ecosystem Restoration Feasibility Study

Paseo de las Iglesias Santa Cruz River Ecosystem Restoration Feasibility Study Jennifer Becker, CFM & Thomas Helfrich, Project Manager of Pima County Flood Control District, Water Resources Division In partnership with the US Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) Good morning ladies and gentlemen. My name is Jennifer Becker. I’m a Program Coordinator with the Pima County Flood Control District, Water Resources Division and I will be presenting the results of the Paseo de las Iglesias Feasibility Study. This study is a joint effort by the Pima County Flood Control District and the US Army Corps of Engineers to determine if the Federal Government can share the costs of restoring the ecosystem along the the Santa Cruz River in south-central Tucson. Æ Next slide 1 SOME STAKEHOLDERS AND PARTICIPANTS Pima County State and federal agencies ¾ Department of Transportation Pima Association of Governments ¾ Cultural Resources San Xavier Nation, Tohono ¾ Natural Resources, Parks and O’odham Nation Recreation ¾ Real Property Local environmental organizations City of Tucson Local and national consulting ¾ Rio Nuevo companies ¾ Tucson Origins Cultural Park University of Arizona ¾ Economic Development Pima Community College ¾ Parks and Recreation ¾ Transportation Engineering Local neighborhood groups ¾ Comprehensive Planning Citizens In additions to the FCD & USACE, other participating stakeholders include various departments in Pima County and City of Tucson government, Arizona Department of Game and Fish, US Fish and Wildlife, local colleges & universities, local Indian Nations, environmental organizations, consulting companies, and individual citizens and citizen groups. Æ Next slide 2 Today’s Presentation • Study Area • Problem Summary • Public Involvement • Project Objectives • Study Considerations • Project Alternatives • Recommended Plan • Proposed Schedule • Documents and Contacts Today I would like to summarize the plan formulation process and present the findings of the study, including a description of the recommended plan to help to restore a functioning ecosystem. -

The Grand Bank's Southeast Shoal Concentrates the Highest Overall

Template for Submission of Scientific Information to Describe Areas Meeting Scientific Criteria for Ecologically or Biologically Significant Marine Areas Title/Name of the area: Southeast Shoal, Grand Bank Presented by (Daniela Diz, WWF-Canada, Sr. Marine Policy Officer, [email protected]; tel: +1.902.482.1105, ext. 35) Abstract (in less than 150 words) The Grand Bank’s Southeast Shoal concentrates the highest overall benthic biomass of the Grand Banks. It also presents: a unique offshore capelin spawning and yellowtail nursery grounds, unique shallow, sandy habitat, cetacean and seabird aggregation and feeding grounds, American plaice nursery habitat, a spawning ground for the depleted Atlantic cod, reproduction area for striped wolffish, and unique populations of blue mussels and wedge clams. This area has been previously identified as an EBSA by DFO in Canada, and as a Vulnerable Marine Ecosystem (VME) indicator element by NAFO. Introduction (To include: feature type(s) presented, geographic description, depth range, oceanography, general information data reported, availability of models) The Southeast Shoal (area east of 51o W and south of 45oN) extends to the edge of the Grand Bank off Newfoundland. It straddles between areas of national jurisdiction and the high seas. Its unique features provide essential habitat for a number of species, playing an important role in the productivity of the Grand Banks ecosystems, which has sustained exceptionally abundant and commercially valuable marine life for centuries. It comprises a relict beach ecosystem containing unusual offshore populations of blue mussel and wedge clam, and offshore capelin spawning ground. The area is also important for threatened and/or declining species, given the currently severely altered state of the Northwest Atlantic ecosystem and the importance of the area as a nursery habitat for cod, home to an offshore spawning population of capelin (an important forage species for groundfish), a discrete population of humpback whales, and migrating leatherback and loggerhead turtles. -

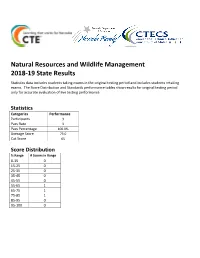

Natural Resources and Wildlife Management Statistics

Natural Resources and Wildlife Management 2018-19 State Results Statistics data includes students taking exams in the original testing period and includes students retaking exams. The Score Distribution and Standards performance tables show results for original testing period only for accurate evaluation of live testing performance. Statistics Categories Performance Participants 3 Pass Rate 3 Pass Percentage 100.0% Average Score 73.0 Cut Score 65 Score Distribution % Range # Scores in Range 0-15 0 15-25 0 25-35 0 35-45 0 45-55 0 55-65 1 65-75 1 75-85 1 85-95 0 95-100 0 Natural Resources and Wildlife Management 1) CONTENT STANDARD 1.0: EXPLORE NATURAL RESOURCE SCIENCE AND MANAGEMENT 75.93% 1) Performance Standard 1.1 : Investigate the Relationship Between Natural Resources and Society, Including Conflict Management 72.22% 1) 1.1.1 Define natural resource management 77.78% 3) 1.1.3 Describe human dependency and demands on natural resources 88.89% 4) 1.1.4 Explain natural resource conservation 66.67% 5) 1.1.5 Investigate the effects of multiple uses of natural resources (e.g., recreation, mining, agriculture, forestry, public lands grazing, etc.) 66.67% 6) 1.1.6 Analyze societal issues related to natural resource management 50% 2) Performance Standard 1.2 : Explain Interrelationships Between Natural Resources and Humans in Managing Natural Environments 86.67% 1) 1.2.1 Explain the effects and/or trade-off of population growth, greater energy consumption, and increased technology and development on natural resources and the environment 83.33% -

For-74: a Guide to Urban Habitat Conservation Planning

FOR-74 A Guide to Urban Habitat Conservation Planning Thomas G. Barnes, Extension Wildlife Specialist Lowell Adams, National Institute for Urban Wildlife entuckians value their forests and Kother natural resources for aes- Guidelines for Considering Wildlife in the Urban Development thetic, recreational, and economic Process significance, so over the past several Promote habitats that will have the food, cover, water, and living space that decades they have become increasingly all wildlife require by following these guidelines: concerned about the loss of wildlife • Before development, maximize open space and make an effort to protect the habitat and greenspace. Urban and most valuable wildlife habitat by placing buildings on less important portions suburban development is one of the of the site. Choosing cluster development, which is flexible, can help. leading causes of this loss: A recent • Provide water, and design stormwater control impoundments to benefit wildlife. study indicated that every day in • Use native plants that have value for wildlife as well as aesthetic appeal. Kentucky more than 100 acres of rural • Provide bird-feeding stations and nest boxes for cavity-nesting birds like land is being converted to urban house wrens and wood ducks. development. • Educate residents about wildlife conservation, using, for example, informa- Because concern for loss of tion packets or a nature trail through open space. greenspace is not new, we have for • Ensure a commitment to managing urban wildlife habitats. some time created attractive urban greenspace environments with our parks and backyards. These The publication can also be useful to A landscape is a large area com- greenspaces have been created not so the average homeowner in understand- posed of ecosystems (the plants, much for wildlife habitats as for people ing the complex issues involved in animals, other living organisms, and to enjoy, but the potential for wildlife landscape planning and wildlife their physical surroundings). -

Stream Visual Assessment Manual

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Stream Visual Assessment Manual Cane River, credit USFWS/Gary Peeples U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Conasauga River, credit USFWS Table of Contents Introduction ..............................................................................................................................1 What is a Stream? .............................................................................................................1 What Makes a Stream “Healthy”? .................................................................................1 Pollution Types and How Pollutants are Harmful ........................................................1 What is a “Reach”? ...........................................................................................................1 Using This Protocol..................................................................................................................2 Reach Identification ..........................................................................................................2 Context for Use of this Guide .................................................................................................2 Assessment ........................................................................................................................3 Scoring Details ..................................................................................................................4 Channel Conditions ...........................................................................................................4 -

The Pecos River Ecosystem Project Progress Report

2004 The Pecos River Ecosystem Project Progress Report Charles R. Hart, Ph.D. Assoc. Professor and Extension Range Specialist Texas Cooperative Extension The Texas A&M University System Background of Situation Saltcedar (Tamarix spp.) is an introduced phreatophyte in western North America. The plant was estimated to occupy well over 600,000 ha of riparian acres in 1965 (Robinson 1965). Saltcedar is a vigorous invader of riparian, rangeland, and moist pastures. Saltcedar was introduced into the United States as an ornamental in the early 1800's. In the early 1900's, government agencies and private landowners began planting saltcedar for stream bank erosion control along such rivers as the Pecos River in New Mexico. The plant has spread down the Pecos River into Texas and is now known to occur along the river south of Interstate 10. More recently the plant has become a noxious plant not only along rivers and their tributaries, but also along irrigation ditch banks, low-lying areas that receive extra runoff accumulation, and areas with high water tables. In addition, many CRP acres in central Texas are being invaded with saltcedar. Saltcedar is a prolific seeder over a long period of time (April through October). Early seedling recruitment is very slow but once established, seedlings grow faster than native plants (Tomanek and Ziegler 1960). Once mature the plant becomes well established with deep roots that occupy the capillary zone above the water table with some roots in the zone of saturation (Schopmeyer 1974). The plant can quickly dominate an area, out-competing native plants for sunlight, moisture, and nutrients. -

Biodiversity Conservation and Habitat Management

CONTENTS BIODIVERSITY CONSERVATION AND HABITAT MANAGEMENT Biodiversity Conservation and Habitat Management - Volume 1 No. of Pages: 458 ISBN: 978-1-905839-20-9 (eBook) ISBN: 978-1-84826-920-0 (Print Volume) Biodiversity Conservation and Habitat Management - Volume 2 No. of Pages: 428 ISBN: 978-1-905839-21-6 (eBook) ISBN: 978-1-84826-921-7 (Print Volume) For more information of e-book and Print Volume(s) order, please click here Or contact : [email protected] ©Encyclopedia of Life Support Systems (EOLSS) BIODIVERSITY CONSERVATION AND HABITAT MANAGEMENT CONTENTS Preface xv VOLUME I Biodiversity Conservation and Habitat Management : An Overview 1 Francesca Gherardi, Dipartimento di Biologia Animale e Genetica, Università di Firenze, Italy Claudia Corti, California Academy of Sciences, San Francisco CA, U.S.A. Manuela Gualtieri, Dipartimento di Scienze Zootecniche, Università di Firenze, Italy 1. Introduction: the amount of biological diversity 2. Diversity in ecosystems 2.1. African wildlife systems 2.2. Australian arid grazing systems 3. Measures of biodiversity 3.1. Species richness 3.2. Shortcuts to monitoring biodiversity: indicators, umbrellas, flagships, keystones, and functional groups 4. Biodiversity loss: the great extinction spasm 5. Causes of biodiversity loss: the “evil quartet” 5.1. Over-harvesting by humans 5.2. Habitat destruction and fragmentation 5.3. Impacts of introduced species 5.4. Chains of extinction 6. Why conserve biodiversity? 7. Conservation biology: the science of scarcity 8. Evaluating the status of a species: extinct until proven extant 9. What is to be done? Conservation options 9.1. Increasing our knowledge 9.2. Restore habitats and manage them 9.3. -

Wildlife Management Activities and Practices

WILDLIFE MANAGEMENT ACTIVITIES AND PRACTICES COMPREHENSIVE WILDLIFE MANAGEMENT PLANNING GUIDELINES for the Edwards Plateau and Cross Timbers & Prairies Ecological Regions Revised April 2010 The following Texas Parks & Wildlife Department staff have contributed to this document: Mike Krueger, Technical Guidance Biologist – Lampasas Mike Reagan, Technical Guidance Biologist -- Wimberley Jim Dillard, Technical Guidance Biologist -- Mineral Wells (Retired) Kirby Brown, Private Lands and Habitat Program Director (Retired) Linda Campbell, Program Director, Private Lands & Public Hunting Program--Austin Linda McMurry, Private Lands and Public Hunting Program Assistant -- Austin With Additional Contributions From: Kevin Schwausch, Private Lands Biologist -- Burnet Terry Turney, Rare Species Biologist--San Marcos Trey Carpenter, Manager, Granger Wildlife Management Area Dale Prochaska, Private Lands Biologist – Kerr Wildlife Management Area Nathan Rains, Private Lands Biologist – Cleburne TABLE OF CONTENTS Comprehensive Wildlife Management Planning Guidelines Edwards Plateau and Cross Timbers & Prairies Ecological Regions Introduction Specific Habitat Management Practices HABITAT CONTROL EROSION CONTROL PREDATOR CONTROL PROVIDING SUPPLEMENTAL WATER PROVIDING SUPPLEMENTAL FOOD PROVIDING SUPPLEMENTAL SHELTER CENSUS APPENDICES APPENDIX A: General Habitat Management Considerations, Recommendations, and Intensity Levels APPENDIX B: Determining Qualification for Wildlife Management Use APPENDIX C: Wildlife Management Plan Overview APPENDIX D: Livestock