Writings from Peru and India Through a Postcolonial Lens

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Epic Imagination in Contemporary Indian Literature

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School May 2017 Modern Mythologies: The picE Imagination in Contemporary Indian Literature Sucheta Kanjilal University of South Florida, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the South and Southeast Asian Languages and Societies Commons Scholar Commons Citation Kanjilal, Sucheta, "Modern Mythologies: The pE ic Imagination in Contemporary Indian Literature" (2017). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/6875 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Modern Mythologies: The Epic Imagination in Contemporary Indian Literature by Sucheta Kanjilal A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy with a concentration in Literature Department of English College of Arts and Sciences University of South Florida Major Professor: Gurleen Grewal, Ph.D. Gil Ben-Herut, Ph.D. Hunt Hawkins, Ph.D. Quynh Nhu Le, Ph.D. Date of Approval: May 4, 2017 Keywords: South Asian Literature, Epic, Gender, Hinduism Copyright © 2017, Sucheta Kanjilal DEDICATION To my mother: for pencils, erasers, and courage. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS When I was growing up in New Delhi, India in the late 1980s and the early 1990s, my father was writing an English language rock-opera based on the Mahabharata called Jaya, which would be staged in 1997. An upper-middle-class Bengali Brahmin with an English-language based education, my father was as influenced by the mythological tales narrated to him by his grandmother as he was by the musicals of Broadway impressario Andrew Lloyd Webber. -

Famous Indian Classical Musicians and Vocalists Free Static GK E-Book

oliveboard FREE eBooks FAMOUS INDIAN CLASSICAL MUSICIANS & VOCALISTS For All Banking and Government Exams Famous Indian Classical Musicians and Vocalists Free static GK e-book Current Affairs and General Awareness section is one of the most important and high scoring sections of any competitive exam like SBI PO, SSC-CGL, IBPS Clerk, IBPS SO, etc. Therefore, we regularly provide you with Free Static GK and Current Affairs related E-books for your preparation. In this section, questions related to Famous Indian Classical Musicians and Vocalists have been asked. Hence it becomes very important for all the candidates to be aware about all the Famous Indian Classical Musicians and Vocalists. In all the Bank and Government exams, every mark counts and even 1 mark can be the difference between success and failure. Therefore, to help you get these important marks we have created a Free E-book on Famous Indian Classical Musicians and Vocalists. The list of all the Famous Indian Classical Musicians and Vocalists is given in the following pages of this Free E-book on Famous Indian Classical Musicians and Vocalists. Sample Questions - Q. Ustad Allah Rakha played which of the following Musical Instrument? (a) Sitar (b) Sarod (c) Surbahar (d) Tabla Answer: Option D – Tabla Q. L. Subramaniam is famous for playing _________. (a) Saxophone (b) Violin (c) Mridangam (d) Flute Answer: Option B – Violin Famous Indian Classical Musicians and Vocalists Free static GK e-book Famous Indian Classical Musicians and Vocalists. Name Instrument Music Style Hindustani -

Maitreyi Pushpa Books Pdf

Maitreyi pushpa books pdf Continue Maitreyi PushpaBorn (1944-11-30) November 30, 1944 (age 75)Aligarh district, IndiaOccupationNovelistGenreIndian women's literature Maitreyi Pushpa (मै ेयी पुपा) (born November 30, 1944), is a Hindi fiction writer. An outstanding Hindi writer, Maitreya Pushpa has ten novels and seven collections of short stories to her credit, and she also writes prolifically for newspapers on topical issues concerning women, and takes an interrogation, bold and challenging position in her writings. She is best known for her Chaco, Alma Kabutari, Jula Nat and the autobiographical novel by Casturi Kundal Base. The early life of Maitrey Pushpa was born in the village of Siikrra in the Aligarh district. She spent her childhood and early years in Hilly, another village in Bundelkhand, near Jansi. Thus, she inherited the vitality of both the cultures and languages of Bundely and Bria, by which she has an enviable team. She graduated in Hindi from Bundelkhand College, Jansi. The career of Maitreyi Pushpa is the author of seven collections of short stories and ten novels, besides writing a regular column in the weekly Rashtriya Sahara. On 29 January 2014, the Delhi Government offered her the position of President of the Delhi Women's Rights Commission. The style of writing, since she is the only female Writer in Hindi who has chosen to write about rural India, her writing is a constant struggle against the feudal system that still prevails in Indian villages. Its main characters are always fearless women who stand up for women's dignity, who suffer and resist male domination. -

Essay About India in Urdu

1 Essay About India In Urdu The literary council of the official Kannada language of the state and more than other 50 language organizations promoting Kannada language threatened state-wide protests against the Urdu bulletin. One missive written by a team of Hindu nationalists from Bhartendu Harishchandra and sent to Madan Mohan Malviya was a scathing attack on the supposed uselessness and alienness of Urdu in British India. A man in his 30s approached and sat beside me, initiating a conver- sation and introducing himself as an off-duty member of the Home Guard. I was unsure how to react to his remark, but he did not seem to be complaining or hostile on the contrary, he was in awe of discovering another set of sounds seemingly alien to him. What had gone wrong. Once again, I got the feeling that Urdu was being treated as alien to Delhi, just as in Patna, although in both places, it has the status of the second official language. The name of the famous emblematic railway station, Mughal Sarai, was metamorphosed into Deen Dyal Upadhya following a chilling fervor by nationalist extremists, just to name one major example. Known as Father of Modern Hindi, Lallu Lal set the tone for Sanskritized Hindi. The recruitment of Urdu teachers was subsequently postponed and exam papers were no longer available in Urdu for public primary schools in Rajasthan. In 2016, the same Rajasthan government removed Urdu author Ismat Chughtai from the Class VIII Hindi textbook. One example Rahman cited was Prem Sagar 1803 by Lallu Lal, in which Arabic and Persian words were purged. -

Download Book

PREMA-SAGARA OR OCEAN OF LOVE THE PREMA-SAGARA OR OCEAN OF LOVE BEING A LITERAL TRANSLATION OF THE HINDI TEXT OF LALLU LAL KAVI AS EDITED BY THE LATE PROCESSOR EASTWICK, FULLY ANNOTATED AND EXPLAINED GRAMMATICALLY, IDIOMATICALLY AND EXEGETICALLY BY FREDERIC PINCOTT (MEMBER OF THE ROYAL ASIATIC SOCIETY), AUTHOR OF THE HINDI ^NUAL, TH^AKUNTALA IN HINDI, TRANSLATOR OF THE (SANSKRIT HITOPADES'A, ETC., ETC. WESTMINSTER ARCHIBALD CONSTABLE & CO. S.W. 2, WHITEHALL GARDENS, 1897 LONDON : PRINTED BY GILBERT AND KIVJNGTON, LD-, ST. JOHN'S HOUSE, CLEKKENWELL ROAD, E.G. TRANSLATOR'S PREFACE IT is well known to aU who have given thought to the languages of India that the or Bhasha as Hindi, the people themselves call is the most diffused and most it, widely important language of India. There of the are, course, great provincial languages the Bengali, Marathi, Panjabi, Gujarat!, Telugu, and Tamil which are immense numbers of spoken by people, and a knowledge of which is essential to those whose lot is cast in the districts where are but the Bhasha of northern India towers they spoken ; high above them both on account of the all, number of its speakers and the important administrative and commercial interests which of attach to the vast stretch territory in which it is the current form of speech. The various forms of this great Bhasha con- of about stitute the mother-tongue eighty-six millions of people, a almost as as those of the that is, population great French and German combined and cover the empires ; they important region hills on the east to stretching from the Rajmahal Sindh on the west and from Kashmir on the north to the borders of the ; the south. -

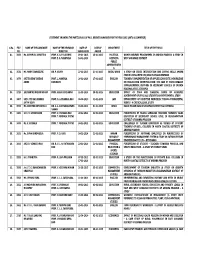

STATEMENT SHOWING the PARTICULARS of Ph.D. DEGREES AWARDED for the YEAR 2015 (ARTS & COMMERCE) S.No. FILE NO. NAME of the CA

STATEMENT SHOWING THE PARTICULARS OF Ph.D. DEGREES AWARDED FOR THE YEAR 2015 (ARTS & COMMERCE) S.No. FILE NAME OF THE CANDIDATE NAME OF THE RESEARCH DATE OF DATE OF DEPARTMENT TITLE OF THE THESIS NO. DIRECTOR SUBMISSION AWARD 01. 3493 Ms. GUNUPUDI SUNEETHA PROF. K. A. P. LAKSHMI 09-01-2013 13-01-2015 POLITICAL WOMEN WELFARE PROGRAMMES IN ANDHRA PRADESH: A STUDY IN PROF. E. A. NARAYANA 14-02-2014 SCIENCE & WEST GODAVARI DISTRICT PUBLIC ADMINISTRATIO N 02. 3532 MS. MARY EVANGELINE DR. P. ARJUN 27-02-2013 21-01-2015 SOCIAL WORK A STUDY ON CRISIS INTERVENTION AND COPING SKILLS AMONG PEOPLE LIVING WITH HIV/AIDS IN VISAKHAPATNAM 03. 3679 SRI TESSEMA TADESSE PROF. L. MANJULA 26-02-2014 27-01-2015 ENGLISH TEACHERS’ IMPLEMENTATION OF APPLIED LINGUISTICS KNOWLEDGE ABEBE DAVIDSON IN FACILITATING COMMUNICATION: THE CASE OF USING ENGLISH SUPRASEGMENTAL FEATURES IN SECONDARY SCHOOLS OF OROMIA REGIONAL STATE, ETHIOPIA 04. 3719 SRI MANTRI MADAN MOHAN PROF. GARA LATCHANNA 26-05-2014 30-01-2015 EDUCATION IMPACT OF YOGA AND CLASSICAL DANCE ON ACADEMIC ACHIEVEMENT OF 9TH CLASS STUDENTS AN EXPERIMENTAL STUDY 05. 3607 SRI C. TEJ RAJ SHARMA PROF. D. S. PRAKASA RAO 06-09-2013 31-01-2015 LAW ENFORCEMENT OF DIRECTIVE PRINCIPLES THROUG FUNDAMENTAL SATYA VIJAY RIGHTS - A CRITICAL LEGAL STUDY 06. 3725 MS. SUMITRA KOTHAPALLI DR. S. A. SURYANARAYANA 03-06-2014 31-01-2015 HINDI RAAHI MASUM RAJA KE UPANYASON MEIN YUG CHETHANA VARMA 07. 3483 Sri E. V. SATISH BABU PROF. D. PRAKASA RAO 28-12-2012 31-01-2015 EDUCATION PERCEPTIONS OF TELUGU LANGUAGE TEACHERS TOWARDS VALUE PROF. -

4 Broadcast Sector

MINISTRY OF INFORMATION AND BROADCASTING Annual Report 2006-2007 CONTENTS Highlights 1. Overview 1 2. Administration 3 3. Information Sector 12 4. Broadcast Sector 53 5. Films Sector 110 6. International Co-operation 169 7. Plan and Non-Plan Programmes 171 8. New Initiatives 184 Appendices I. Organisation Chart of the Ministry 190 II. Media-wise Budget for 2006-2007 and 2007-2008 192 Published by the Director, Publications Division, Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, Government of India Typeset at : Quick Prints, C-111/1, Naraina, Phase - I, New Delhi. Printed at : Overview 3 HIGHLIGHTS OF THE YEAR The 37th Edition of International Film Festival of India-2006 was organized in Goa from 23rd November to 3rd December 2006 in collaboration with State Government of Goa. Shri Shashi Kapoor was the Chief Guest for the inaugural function. Indian Film Festivals were organized under CEPs/Special Festivals abroad at Israel, Beijing, Shanghai, South Africa, Brussels and Germany. Indian films also participated in different International Film Festivals in 18 countries during the year till December, 2006. The film RAAM bagged two awards - one for the best actor and the other for the best music in the 1st Cyprus International Film Festival. The film ‘MEENAXI – A Tale of Three Cities’ also bagged two prizes—one for best cinematography and the other for best production design. Films Division participated in 6 International Film Festivals with 60 films, 4 National Film Festivals with 28 films and 21 State level film festivals with 270 films, during the period 1-04-06 to 30-11-06. Films Division Released 9791 prints of 39 films, in the theatrical circuits, from 1-4-06 to 30-11-06. -

The Sixth String of Vilayat Khan

Published by Context, an imprint of Westland Publications Private Limited in 2018 61, 2nd Floor, Silverline Building, Alapakkam Main Road, Maduravoyal, Chennai 600095 Westland, the Westland logo, Context and the Context logo are the trademarks of Westland Publications Private Limited, or its affiliates. Copyright © Namita Devidayal, 2018 Interior photographs courtesy the Khan family albums unless otherwise acknowledged ISBN: 9789387578906 The views and opinions expressed in this work are the author’s own and the facts are as reported by her, and the publisher is in no way liable for the same. All rights reserved No part of this book may be reproduced, or stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without express written permission of the publisher. Dedicated to all music lovers Contents MAP The Players CHAPTER ZERO Who Is This Vilayat Khan? CHAPTER ONE The Early Years CHAPTER TWO The Making of a Musician CHAPTER THREE The Frenemy CHAPTER FOUR A Rock Star Is Born CHAPTER FIVE The Music CHAPTER SIX Portrait of a Young Musician CHAPTER SEVEN Life in the Hills CHAPTER EIGHT The Foreign Circuit CHAPTER NINE Small Loves, Big Loves CHAPTER TEN Roses in Dehradun CHAPTER ELEVEN Bhairavi in America CHAPTER TWELVE Portrait of an Older Musician CHAPTER THIRTEEN Princeton Walk CHAPTER FOURTEEN Fading Out CHAPTER FIFTEEN Unstruck Sound Gratitude The Players This family chart is not complete. It includes only those who feature in the book. CHAPTER ZERO Who Is This Vilayat Khan? 1952, Delhi. It had been five years since Independence and India was still in the mood for celebration. -

RAS227 Proof 98..122

RESEARCH ARTICLE The Hindi-Speaking Intelligentsia and Agricultural Modernisation in the Colonial Period Sandipan Baksi* Abstract: This paper is a study of the perceptions of the emerging Hindi-speaking intelligentsia about agricultural modernisation in the British colonial period. It discusses the meaning of agrarian change for this emerging class, especially with respect to the interrelationship between the techniques and methods of agricultural production on the one hand, and the socio-economic aspects of agricultural production on the other. It is based on a survey of writings that appeared in some important literary and popular science Hindi periodicals of the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. The study finds that there was a strong perception among Hindi publicists of the colonial period of the utility of science and technology in agriculture. While acknowledging the importance of science, there was an understanding among them that the expansion of production and productivity in agriculture was also dependent on the prevailing socio-economic context. Keywords: history of agriculture, history of science, vernacular periodicals, Hindi periodicals, science in the vernacular, science and colonialism, agriculture and colonialism, popularisation of science, scientific agriculture. In his landmark analysis of the Indian economy of the early 1960s, Daniel Thorner wrote that colonial India suffered from “the world’s most refractory land problem,” because of a “built in depressor” in the structure of its agrarian economy (Thorner 1962). This built-in depressor, a result of the policies implemented by colonial rule, constrained the growth of the productive forces in agriculture. These policies prevented any significant investment in agricultural development, and acted as an inherent disincentive to the adoption of modern methods and techniques by Indian cultivator classes. -

List of Books Available on Calibre Software

LIST OF BOOKS AVAILABLE ON CALIBRE SOFTWARE (PLEASE CONTACT LIBRARY STAFF TO ACCESS CALIBRE) 1. 1.doc · Kamal Swaroop 2. 50 Volume RGS Journal Table of Contents s · Unknown 3. 1836 Asiatic Researches Vol 19 Part 1 s+m · Unknown 4. 1839 Asiatic Researches Vol 19 Part 2 : THE HISTORY, THE ANTIQUITIES, THE ARTS AND SCIENCES, AND LITERATURE ASIA . · Asiatic Society, Calcutta 5. 1839 Asiatic Researches Vol 19 Part 2 s+m · Unknown 6. 1840 Journal Asiatic Society of Bengal Vol 8 Part 1 s+m · Unknown 7. 1840 Journal Asiatic Society of Bengal Vol 8 Part 2 s+m · Unknown 8. 1840 Journal Asiatic Society of Bengal Vol 9 Part 1 s+m · Unknown 9. 1856 JASB Index AR 19 to JASB 23 · Unknown 10. 1856 Journal Asiatic Society of Bengal Vol 24 s+m · Unknown 11. 1862 Journal Asiatic Society of Bengal Vol 30 s+m · Unknown 12. 1866 Journal Asiatic Society of Bengal Vol 34 s+m · Unknown 13. 1867 Journal Asiatic Society of Bengal Vol 35 s+m · Unknown 14. 1875 Journal Asiatic Society of Bengal Vol 44 Part 1 s+m · Unknown 15. 1875 Journal Asiatic Society of Bengal Vol 44 Part 2 s+m · Unknown 16. 1951-52.PMD · Unknown 17. 1952-53-(Final).PMD · Unknown 18. 1953-54.pmd · Unknown 19. 1954-55.pmd · Unknown 20. 1955-56.pmd · Unknown 21. 1956-57.pmd · Unknown 22. 1957-58(interim) 1957-58-1958-59 · Unknown 23. 62569973-Text-of-Justice-Soumitra-Sen-s-Defence · Unknown 24. ([Views of the East; Comprising] India, Canton, [And the Shores of the Red Sea · Robert Elliot 25. -

MUSIC (Lkaxhr) 1. the Sound Used for Music Is Technically Known As (A) Anahat Nada (B) Rava (C) Ahat Nada (D) All of the Above

MUSIC (Lkaxhr) 1. The sound used for music is technically known as (a) Anahat nada (b) Rava (c) Ahat nada (d) All of the above 2. Experiment ‘Sarna Chatushtai’ was done to prove (a) Swara (b) Gram (c) Moorchhana (d) Shruti 3. How many Grams are mentioned by Bharat ? (a) Three (b) Two (c) Four (d) One 4. What are Udatt-Anudatt ? (a) Giti (b) Raga (c) Jati (d) Swara 5. Who defined the Raga for the first time ? (a) Bharat (b) Matang (c) Sharangdeva (d) Narad 6. For which ‘Jhumra Tala’ is used ? (a) Khyal (b) Tappa (c) Dhrupad (d) Thumri 7. Which pair of tala has similar number of Beats and Vibhagas ? (a) Jhaptala – Sultala (b) Adachartala – Deepchandi (c) Kaharva – Dadra (d) Teentala – Jattala 8. What layakari is made when one cycle of Jhaptala is played in to one cycle of Kaharva tala ? (a) Aad (b) Kuaad (c) Biaad (d) Tigun 9. How many leger lines are there in Staff notation ? (a) Five (b) Three (c) Seven (d) Six 10. How many beats are there in Dhruv Tala of Tisra Jati in Carnatak Tala System ? (a) Thirteen (b) Ten (c) Nine (d) Eleven 11. From which matra (beat) Maseetkhani Gat starts ? (a) Seventh (b) Ninth (c) Thirteenth (d) Twelfth Series-A 2 SPU-12 1. ? (a) (b) (c) (d) 2. ‘ ’ ? (a) (b) (c) (d) 3. ? (a) (b) (c) (d) 4. - ? (a) (b) (c) (d) 5. ? (a) (b) (c) (d) 6. ‘ ’ ? (a) (b) (c) (d) 7. ? (a) – (b) – (c) – (d) – 8. ? (a) (b) (c) (d) 9. ? (a) (b) (c) (d) 10. -

Mughul-E-Azam

Mughul-E-Azam Dr Niva Bhandari for MA English Students 5/2/2011 1 CURAJ • Released Aug 5, 1960 • Director /Script : K Asif • B&W/Colour, 173 minutes • Dialogue: Kamaal Amrohi, Aman, Wahajat Mirza, Ehsan Rizvi • Cinematography: R. D. Mathur • Music: Naushad • Lyrics: Shakeel Badayuni • Cast: Prithviraj Kapoor, Dilip Kumar as Salim, Durga Khote, Madhubala as Nadira/Anarkali, Ajit Dr Niva Bhandari for MA English Students 5/2/2011 2 CURAJ Dr Niva Bhandari for MA English Students 5/2/2011 3 CURAJ • Indian Grand Historical epic • A sweeping epic - There are battle scenes, romantic yearning, courtly intrigue/scheme/plot, and of course singing and dancing. • Imposing grandeur, breathtaking beauty and, most important of all, its emotional energy • The plot is based on the famous Urdu play Anarkali by Imtiaz Ali Taj • The movie took 9 years in the making • The most expensive Bollywood production ever till 2009 • In 2004, the entire movie was digitally colourized and released for yet another popular run in Indian theaters Dr Niva Bhandari for MA English Students 5/2/2011 4 CURAJ Fact: • Shah Rukh Khan’s father Meer Taj Mohammad came to the sets of the film, hoping to get a role, but was told to stand in the line for extras. • He left and never returned. Dr Niva Bhandari for MA English Students 5/2/2011 5 CURAJ Muslim Cinema • Muslim Cinema can be broken down into two categories. – The first is native cinema of Muslim-majority countries like Iran, Egypt, and Turkey. – The second is cinema of Muslim-minority countries like the U.S., France, and India.