Accident Report Collision with Bridge Spirit of Resolution 8 October 2005 Class B

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

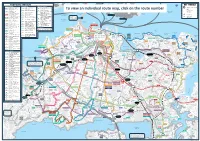

To View an Individual Route Map, Click on the Route Number

Ngataringa Bayswater PROPOSED SERVICES Bay KEY SYMBOLS FREQUENT SERVICES LOCAL SERVICES PEAK PERIOD SERVICES Little Shoal Station or key connection point Birkenhead Bay Northwestern Northwest to Britomart via Crosstown 6a Crosstown 6 extension to 101 Pt Chevalier to Auckland University services Northwestern Motorway and Selwyn Village via Jervois Rd Northcote Cheltenham Rail Line Great North Rd To viewNorthcote an individualPoint route map, click on the route number (Passenger Service) Titirangi to Britomart via 106 Freemans Bay to Britomart Loop 209 Beach North Shore Northern Express routes New North Rd and Blockhouse Bay Stanley Waitemata service Train Station NX1, NX2 and NX3 138 Henderson to New Lynn via Mangere Town Centre to Ferries to Northcote, Point Harbour City LINK - Wynyard Quarter to Avondale Peninsula Wynyard Quarter via Favona, Auckland Harbour Birkenhead, West Harbour, North City Link 309X Bridge Beach Haven and Karangahape Rd via Queen St 187 Lynfield to New Lynn via Mangere Bridge, Queenstown Rd Ferries to West Harbour, Hobsonville Head Ferry Terminal Beach Haven and Stanley Bay (see City Centre map) Blockhouse Bay and Pah Rd (non stop Hobsonville Services in this Inner LINK - Inner loop via Parnell, Greenwoods Corner to Newmarket) Services to 191 New Lynn to Blockhouse Bay via North Shore - direction only Inner Link Newmarket, Karangahape Rd, Avondale Peninsula and Whitney St Panmure to Wynyard Quarter via Ferry to 701 Lunn Ave and Remuera Rd not part of this Ponsonby and Victoria Park 296 Bayswater Devonport Onehunga -

Engineering Walk Final with out Cover Re-Print.Indd

Heritage Walks _ The Engineering Heritage of Auckland 5 The Auckland City Refuse Destructor 1905 Early Electricity Generation 1908 9 Wynyard Wharf 1922 3 13 Auckland Electric 1 Hobson Wharf The New Zealand National Maritime Museum Tramways Co. Ltd Princes Wharf 1937 1989 1899–1902 1921–24 12 7 2 The Viaduct 10 4 11 The Auckland Gasworks, Tepid Baths Lift Bridge The Auckland Harbour Bridge The Sky Tower Viaduct Harbour first supply to Auckland 1865 1914 1932 1955-59 1997 1998-99 Route A 1850 1860 1870 1880 1890 1900 1910 1920 1930 1940 1950 1960 1970 1980 1990 2000 Route B 14 Old 15 Auckland High Court 13 The Old Synagogue 1 10 Albert Park 1942 Government 1865-7 1884-85 The Ferry Building House 1912 1856 16 Parnell Railway Bridge and Viaduct 5 The Dingwall Building 1935 1865-66 3 Chief Post Office 1911 The Britomart Transport Centre 7 The Ligar Canal, named 1852, improved 1860s, covered 1870s 6 8 Civic Theatre 1929 2001-2004 New Zealand 9 Guardian Trust The Auckland Town Hall Building 1911 1914 17 The Auckland Railway Station 1927-37 11 Albert Barracks Wall 2 Queens Wharf 1913 1846-7 4 The Dilworth Building 1926 12 University of Auckland Old Arts Building 1923-26 10 Route A, approx 2.5 hours r St 9 Route B, approx 2.5 hours Hame Brigham St Other features Jellicoe St 1 f r ha W Madden s 2 e St St rf Princ a 12 h 13 W s Beaumont START HERE een 11 Qu Pakenha m St St 1 son ob H St bert y St n St Gaunt St Al 2 e e Pakenh S ue ket Place H1 am Q Hals St 3 ar Customs M St Quay St 3 4 18 NORTH Sw 8 St anson S Fanshawe t 5 7 6 Wyn Shortla dham nd -

Auckland's Urban Form

A brief history of Auckland’s urban form April 2010 A brief history of Auckland’s urban form April 2010 Introduction 3 1840 – 1859: The inaugural years 5 1860 – 1879: Land wars and development of rail lines 7 1880 – 1899: Economic expansion 9 1900 – 1929: Turning into a city 11 1930 – 1949: Emergence of State housing provision 13 1950 – 1969: Major decisions 15 1970 – 1979: Continued outward growth 19 1980 – 1989: Intensifi cation through infi ll housing 21 1990 – 1999: Strategies for growth 22 2000 – 2009: The new millennium 25 Conclusion 26 References and further reading 27 Front cover, top image: North Shore, Auckland (circa 1860s) artist unknown, Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tamaki, gift of Marshall Seifert, 1991 This report was prepared by the Social and Economic Research and Monitoring team, Auckland Regional Council, April 2010 ISBN 978-1-877540-57-8 2 History of Auckland’s Urban Form Auckland region Built up area 2009 History of Auckland’s Urban Form 3 Introduction This report he main feature of human settlement in the Auckland region has been the development This report outlines the of a substantial urban area (the largest in development of Auckland’s New Zealand) in which approximately 90% urban form, from early colonial Tof the regional population live. This metropolitan area settlement to the modern Auckland is located on and around the central isthmus and metropolis. It attempts to capture occupies around 10% of the regional land mass. Home the context and key relevant to over 1.4 million people, Auckland is a vibrant centre drivers behind the growth in for trade, commerce, culture and employment. -

ONEHUNGA Transform Onehunga

ONEHUNGA Transform Onehunga High Level Project Plan – March 2017 ABBREVIATIONS AT Auckland Transport ATEED Auckland Tourism, Events and Economic Development Ltd CCO Council-controlled organisation the council Auckland Council HLPP High Level Project Plan HNZ Housing New Zealand LTP Long-term Plan Panuku Panuku Development Auckland AUP Auckland Unitary Plan (Operative in part) SOI Statement of Intent 2 PANUKU DEVELOPMENT AUCKLAND CONTENTS 1.0 INTRODUCTION 5 3.7 Infrastructure 34 7.3.4 Manukau Harbour Forum 68 1.1 Mihi 8 3.7.1 Social infrastructure 34 7.3.5 Large Infrastructure Integration Group 68 1.2 Shaping spaces for Aucklanders to love 9 3.7.2 Physical infrastructure 34 7.3.6 Onehunga community champions 68 1.3 Panuku – who we are 10 3.7.3 Infrastructure projects 35 7.3.7 Baseline engagement 69 1.4 Why Onehunga? 12 7.3.8 Auckland Council family 69 4.0 PANUKU PRINCIPLES 39 1.5 Purpose of this High Level Project Plan 13 7.3.9 Place-led engagement 69 FOR TRANSFORM PROJECTS 1.6 Developing the Transform Onehunga story 14 7.4 Place-making for Onehunga 70 4.1 Panuku’s commitment 40 2.0 VISION THEMES FOR 17 4.2 Panuku principles for Transform projects 40 8.0 PROPOSED IMPLEMENTATION 73 TRANSFORM ONEHUNGA 8.1 Development strategy 74 5.0 GOALS FOR TRANSFORM ONEHUNGA 43 8.1.1 Key infl uences 74 3.0 CONTEXT 21 6.0 STRATEGIC MOVES 47 8.1.2 Proposed delivery strategy 74 3.1 Background 22 6.1 Strategic Move: Build on existing strengths (RETAIN) 50 8.2 Town Centre Core 76 3.2 Mana Whenua 23 6.1.1 Potential projects and initiatives 51 8.3 Town Centre -

1967 No 8 Auckland Harbour Board (Reclamation

1468 Auckland Harbour Board (Reclamation) 1967, No. B Empowering ANALYSIS 7. Authority to lease or license Title 8. Validation and empowering of cer 1. Short Title tain reclamation by the Onehunga 2. Interpretation Borough Council 3. Special Act 9. Local authority boundaries 4. Authority to reclaim 10. Cancellation of trusts and reserva 5. Authority to develop tions 6. Reclamation or development not to 11. Powers of District Land Registrar prejudice other powers and rights Schedules 1967, No_ 8-Local An Act to authorise the Auckland Harbour Board to reclaim from the sea certain tidal lands in the Waitemata and Manukau Harbours and to develop such reclaimed land and other lands for industrial, commercial, and other purposes [25 August 1967 BE IT ENACTED by the General Assembly of New Zea land in Parliament assembled, and by the authority of the same, as follows: 1. Short Title-This Act may be cited as the Auckland Harbour Board (Reclamations) Empowering Act 1967 . .2. Interpretation-In this Act, unless the context other WIse reqUlres,- "Board" means the Auckland Harbour Board; "Local authority" means a local authority within the meaning of that term in the Public Works Act 1928. 3. Special Act-This Act shall be deemed to be a special Act within the meaning of the Harbours Act 1950. 1967, No. 8 Auckland Harbour Board (Reclamation) l469 Empowering 4. Authority to reclaim-( 1) Subject to the provisions of the Harbours Act 1950, and of this Act, but notwithstanding anything contained in subsection (3) of section 175 of the Harbours Act 1950, the Board may from time to time re claim from the sea the areas described in the First Schedule to this Act or any part or parts thereof save and except the area described in section B of Part IV of that schedule. -

History of Concrete Bridges in New Zealand

HISTORY OF CONCRETE BRIDGES IN NEW ZEALAND JAMIL KHAN1, GEOFF BROWN2 1 Senior Associate, Beca Ltd 2 Technical Director, Beca Ltd SUMMARY Concrete is one of the most cost effective, durable and aesthetic construction materials and can provide many advantages over other materials. The history of bridge construction in New Zealand has proved that concrete is an excellent material for constructing bridges, and in particular bridges that use beams, columns and arches as the main load bearing elements. It is remarkable that New Zealand, as a remote country at the end of the Victorian period, made considerable early use of concrete in bridge construction. Kiwi engineers love new ideas and embrace new technologies. New Zealand bridge engineers, from the early days, were not afraid to take on the challenge of working with a new and innovative material. The first reinforced concrete bridge was built over the Waters of Leith in Dunedin in 1903. In 1910 the Grafton Bridge in Auckland became the world’s longest reinforced concrete arch bridge, 21 years later the Kelburn Viaduct was built in Wellington. Taranaki was especially forward-looking in using concrete arch bridges and has many fine examples. In 1954 another major development occurred when the Hutt Estuary Bridge used post-tensioned pre-stressed concrete for the first time in New Zealand. This led to the construction of New Zealand’s first pre-stressed concrete box girder bridge on the Wanganui Motorway in 1962. Pre-stressed concrete made slim and elegant construction possible, like the 1987 Hāpuawhenua Viaduct on the North Island Main Trunk railway line. -

SMART - Way Forward

Board Meeting| 27 June 2016 Agenda item no. 11.6 Closed Session CONFIDENTIAL SMART - way forward Recommendations That the Board resolves the following: i. That Management discount heavy rail to the airport from any further option development due to its poor value for money proposition; ii. Instructs Management to: a) Develop a bus based high capacity mode to the same level of detail as the LRT option to allow a value for money comparison with the LRT option and submit this to ATAP for consideration; b) Refine the LRT option further to address the high risk issues as articulated in this paper; c) Report back to the Board on the findings of the bus based high capacity mode and LRT comparison. d) Progress with route protection for bus / light rail, not heavy rail; e) Align the SMART and CAP business cases to enable the consideration of an integrated public transport system between the city centre and the airport f) Progress the business case development of the RTN route between Botany, Manukau and the airport and align this with NZTA’s business case development for SH20B. Executive summary The Sub-Regional Strategy that arose from the South Western Airport Multi Modal Corridor Project (SWAMMCP) prepared in 2011 concluded that investment in high capacity public transport services will be needed as part of an investment strategy in combination with state highway and local transport improvements. For the public transport component, the strategy looked at LRT, BRT and heavy rail. It ruled out LRT and BRT and concluded that the Rail Loop package would provide the best network resilience and highest benefits. -

Auckland Transport Alignment Project April 2018

Auckland Transport Alignment Project April 2018 Foreword I welcome the advice provided by the Auckland Transport Alignment Project (ATAP). The ATAP package is a transformative transport programme. Investment in transport shapes our city’s development and is a key contributor to economic, social and environmental goals. The direction signalled in this update is shared by Government and Auckland Council and demonstrates our commitment to working together for a better Auckland. Auckland is facing unprecedented population growth, and over the next 30 years a million more people will call Auckland home. Growth brings opportunities but when combined with historic under- investment in infrastructure the strain on the Auckland transport system is unrelenting. Existing congestion on our roads costs New Zealand’s economy $1.3b annually. We need to do things differently to what has been done in the past. Auckland needs a transport system that provides genuine choice for people, enables access to opportunities, achieves safety, health and environmental outcomes and underpins economic development. Our aspiration must be to make sure Auckland is a world class city. Auckland’s success is important not just for Aucklanders, but for our country’s long-term growth and productivity. The Government and Auckland Council have agreed to a transformative and visionary plan. ATAP is a game-changer for Auckland commuters and the first-step in easing congestion and allowing Auckland to move freely. I believe this ATAP package marks a significant step in building a modern transport system in Auckland. ATAP accelerates delivery of Auckland’s rapid transit network, with the aim of unlocking urban development opportunities, encourages walking and cycling, and invests in public transport, commuter and freight rail and funds road improvements. -

Before a Board of Inquiry East West Link Proposal

BEFORE A BOARD OF INQUIRY EAST WEST LINK PROPOSAL Under the Resource Management Act 1991 In the matter of a Board of Inquiry appointed under s149J of the Resource Management Act 1991 to consider notices of requirement and applications for resource consent made by the New Zealand Transport Agency in relation to the East West Link roading proposal in Auckland Closing Legal submissions on behalf of Auckland Transport dated 13 September 2017 BARRISTERS AND SOLICITORS A J L BEATSON SOLICITOR FOR THE SUBMITTER AUCKLAND LEVEL 22, VERO CENTRE, 48 SHORTLAND STREET PO BOX 4199, AUCKLAND 1140, DX CP20509, NEW ZEALAND TEL 64 9 916 8800 FAX 64 9 916 8801 EMAIL [email protected] MAY IT PLEASE THE BOARD Introduction 1. Auckland Transport (AT) supports the East West Link (EWL) Project. It considers the EWL Project will result in the following key transport related benefits: (a) It responds to an identified need to improve freight and general traffic efficiency. The EWL will improve travel times and travel time reliability between businesses in the Onehunga-Penrose industrial area and State Highways 1 and 20; (b) It improves cycling and walking facilities with over double the linear length of walking and cycling facilities in the project area compared with the existing network, and related safety and accessibility improvements between Mangere Bridge, Onehunga and Sylvia Park; (c) It improves journey time reliability for buses between State Highway 20 and the Onehunga Town Centre; and (d) Network resilience, lower traffic volumes on residential streets and arterial routes, and improved connectivity between Onehunga Town Centre and Onehunga Port. -

Mangere Bridge Monthly Newsletter

98 5 1 01 APRIL 2 APRIL VOLUME Compliments of Webtastix Internet Services www.webtastix.net What’s on in the Bridge MONDAY Guides 6-8pm. The amazing Entertainment books are coming out soon for 2015-2016! we are now CMA Day Care 9:30am - 12:30pm. taking pre orders to assist with running the newsletter for the year... please contact me Methodist Church Hall. St John Youth - 6:30-8:00pm. to pre order one, the books will be avaliable sometime in April. - Those that pre order Wriggle & Whyme 9:30 - get an extra sheet of vouchers as well! Contact [email protected] to pre School Term only, MB Library Senior Citizens Housie, 1pm order one Bridge Crt Hall TUESDAY Keas 5-6pm Mangere Bridge Community Working Cubs 5-6:30pm Bee – 23 May 2015 WEDNESDAY Brownies 6-7:30pm Mangrove seedling removal - rain or shine Tibetan Buddhist Class 7:30pm Plunket Toy Library 9:30 - 10:30am Mangere Bridge Residents and Ratepayers Association is organising its annual community work- Yoga 6.30 - 8 pm ing bee to remove mangrove seedlings from Shelly Beach and other parts of Kiwi Esplanade fore- Mangere Mountain Education Ctr. shore. This year there’s been a huge influx of mangrove seed pods all along the foreshore and Mangere Bridge Plunket Indoor Bowls the seedlings in our beach area (by the playground and boat club) are particularly worrying. We Names by 7.20pm Mangere Memorial Hall need to get stuck in and get rid of them, or else we’ll lose beach access and our beautiful views. -

Transport Accident Investigation Commission New Zealand

MARINE OCCURRENCE REPORT 02-208 bulk carrier Westport, collision, Onehunga, Manukau Harbour 21 November 2002 TRANSPORT ACCIDENT INVESTIGATION COMMISSION NEW ZEALAND The Transport Accident Investigation Commission is an independent Crown entity established to determine the circumstances and causes of accidents and incidents with a view to avoiding similar occurrences in the future. Accordingly it is inappropriate that reports should be used to assign fault or blame or determine liability, since neither the investigation nor the reporting process has been undertaken for that purpose. The Commission may make recommendations to improve transport safety. The cost of implementing any recommendation must always be balanced against its benefits. Such analysis is a matter for the regulator and the industry. These reports may be reprinted in whole or in part without charge, providing acknowledgement is made to the Transport Accident Investigation Commission. Report 02-208 bulk carrier Westport Collision Onehunga, Manukau Harbour 21 November 2002 Abstract On Thursday 21 November 2002 at about 0938, the bulk cement carrier Westport collided stern first with the Old Mangere Bridge when the controllable pitch propeller mechanism failed during departure from Onehunga. Both the ship and the bridge suffered extensive damage. The safety issues identified included: · the adequacy of knowledge of default conditions for the system · the adequacy of knowledge of correct operating pressures for the controllable pitch propeller. Safety recommendations were made -

Nominations Media Report - 21/08/2013 3:10 P.M

8/21/13 Noms2013MediaReport21151046.html Nominations Media Report - 21/08/2013 3:10 p.m. Address TA Issue Surname First Names Affiliation Phone Email Other Affordable AC Mayor - Auckland Council BERRY Stephen Auckland 021 165 3464 [email protected] 86A School Road Kingsland Auckland 1021 AC Mayor - Auckland Council BRIGHT Penny Independent 09 846 9825 [email protected] 8 Tiffany Close Totara Park Manukau Auckland 2016 AC Mayor - Auckland Council BROWN Len Independent [email protected] AC Mayor - Auckland Council BUTLER Jesse 021 128 3978 [email protected] 15 Woodlands Crescent Browns Bay Auckland 0630 AC Mayor - Auckland Council CHEEL Tricia 027 469 2233 [email protected] www.mycafe.co.nz AC Mayor - Auckland Council DUFFY Paul 0276 888579 [email protected] 5/60 Avenue Road Otahuhu 1062 AC Mayor - Auckland Council GOODE Matthew 0212552981 AC Mayor - Auckland Council HUSSEY Emmett Independent [email protected] Susanna 16A Parnell Road Parnell Auckland 1052 AC Mayor - Auckland Council KRUGER Independent Susara 021 1139789 [email protected] 4 Ethel Street Morningside Auckland 1025 AC Mayor - Auckland Council MINTO John Mana Movement 022 085 0161 [email protected] 09 846 3173 Christians Against AC Mayor - Auckland Council O'CONNOR Phil file:///C:/temp/Noms2013MediaReport21151046.html 1/41 8/21/13 Noms2013MediaReport21151046.html Abortion AC Mayor - Auckland Council PALINO John Independent [email protected] AC Mayor - Auckland Council SHADBOLT Reuben Independent 021 2677764 [email protected]