Onehunga Heritage Survey Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Route 27W - Waikowhai to Britomart Via Mt Eden Rd

Britomart W Quay St B Customs St W a l f Customs B Spark o G t St E A e u Wolfe St a l Parnell Rose S n r a c Arena z h Parnell Gardens y a R d R d e Swanson St d n d s s c l Av ra Tce t a t s o t e u W S st nd n H yndh am S a St u l he g t ve e t S e t u l n T C t k R S S A r e S o d t n d n Albert Y l e t e S o r d o rfi r u s Park o W s e a f t l Auckland G t S b t a b C e r St Marys Q ia l S t or o h S Parnell t N Ponsonby School c A University e College Vi H y s A e h School d Wellesley lfred l ir R St W W St n e is e a S e vo lle t t v ROUTE 27W - WAIKOWHAIr TO BRITOMART VIA MT EDENS RD A Je t sl P S ey a s Herne Bay S r n d Cook St r t n e n E Parnell e h Ponsonby a Na D l pier t ll p e S l R te Intermediate Ir M a d S U t a or t t n S y S P i S B on t ir B o n e s d rig S v w h n t e d ood to s c A n n n s R Bayfield School o i d y o d n t P V e R b S r it m Ponsonby y e t G y n Ayr S R w S o t t Hukanui d o f Reserve St Pauls H a A Coxs Bay Reserve College r yr St d t Rd G R AGGS S hape Auckland d n a t Coxs Bay u t n g S Museum o d S E Park t n e a n Park Rd R a t p r gr e St e Newmarket s o a o tt u e Richmond Rd H K e e Park e W p School d u G s R s a Q d a H n y o B m Grey R ich e r Carlton Gore Rd a v r e Grafton w A D p d Lynn n n p a o o U Newmarket Cr d s n o y R r e ewton Rd n m in N Khyber Pass Rd r a h B li rt k A G l c Newmarket ar i o n M Grafton d e Grey Lynn W N ccombes Rd R t Westmere t n Se y R Park a e d School Arch a n e I r Westmere r W A G Hill St Michaels Seddon Mt Eden School Fields Rid ings Grey Lynn School -

ROUTE 309 & 309X

ROUTE 309 & 309x - MANGERE TOWN CENTRE, FAVONA, ONEHUNGA, PAH RD, CITY t W t S S a S t l t n y l a o t M e S c s e m l yl e St Marys a g u r r a S A y a t H s e Bay Britomart Jervois Rd R B t d S t t Herne Bay e S Cu w S s Mission sha t to Coxs Bay St Marys an r m F n s Q e S u A t a C College e y St Bay ol lb e n Okahu Bay le Vi A u z g cto a T e Hill W r Q a e ia c m lle S t t A a sl S k Ta ey v m s i a r e D St d e ki Rd e n D a Parnell v d c r P t r C A o n S d En Ponsonby o R ok i e t M r h t St T n s i e n W n S P St Pauls li t k s k a n S Auckland t College o n y t Mission Bay a o D i r A n r s o k n F l S University t a t o Westmere e s r S m b S a a T N n y y n ob t l r S e H D e l R u t r AUT n n e P Grey Lynn d b e a e a d G p v u t c t e A S r R a n S i s Q n r H y a n V e s e Ngap r i e e AGGS d l p C m G l v t n i o a R a A r d R R i d R t o R mon S e te a d ch n d v n ou d s K d o t m A m e i u p ape y R s A s o h Rd n v h H a S e e p e g t n o n e d h R ra p t o K a e t t a a t S l K S S f P eo Auckland St t a M e n r v N e Hobson Bay Orakei e G City Hospital A d e n R d u o r R w Pa O e Q rk ld ms m h R M Surre ia t t r r d d y Cr l m r e ill il u o o D R R r n n p 1 d W C N o l Selwyn t p l Kepa Rd n U a n Rd e Orakei College re i rn Ay k Grafton a r G 16 c P St Car M lton 309 Go d n re e R hore Rd R t d S v a S I d i i B A u 309x Grafton R e T o Baradene a Rd k reat North Arch Hill Newmarket i G n d r a K College r d hy n o b t Meadowbank St Peters e a O l c D Mt Eden r r 16 i S g Pa t U d r t College s V n s i p d -

Peter Fraser

N E \V z_E A L A N D S T U D I E S 1!!J BOOK 'RJVIEW by SiiiiOII sheppard Peter Fraser: Master Politician Fraser made more important decisions in more interesting times Margaret Clark (Ed), The Dunmore Press, 1998, $29.95 than Holyoake ever did. ARL!ER THIS YEAR I con International Relations at Victoria Congratulations are due to the E ducted a survey among University, the book is derived from organisers of the conference for academics and other leaders in their a conference held in August 1997, their diligence in assembling a fields asking them to give their part of a series being conducted by roster of speakers capable of appraisal of New Zealand's providing such a broad Prime Ministers according spectrum of perspectives on to the extent to which they Fraser. This multi-faceted made a positive contribu approach pays dividends in tion to the history of the that it reflects the depth of country. From the replies I Fraser's character and the was able to establish a breadth of his contribution to ranking of the Prime New Zealand history. Ministers, from greatest to The first three phases of least effective. Fraser's political career are It was no surprise that discussed; from early Richard Seddon finished in socialist firebrand, to key first place. But I was lieutenant in the first Labour intrigued by the runner up. Government, to wartime It was not the beloved Prime Minister and interna Michael Joseph-Savage, nor tional statesman at the the inspiring Norman Kirk, founding of the United or the long serving Sir Keith Nations. -

'About Turn': an Analysis of the Causes of the New Zealand Labour Party's

Newcastle University e-prints Date deposited: 2nd May 2013 Version of file: Author final Peer Review Status: Peer reviewed Citation for item: Reardon J, Gray TS. About Turn: An Analysis of the Causes of the New Zealand Labour Party's Adoption of Neo-Liberal Policies 1984-1990. Political Quarterly 2007, 78(3), 447-455. Further information on publisher website: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com Publisher’s copyright statement: The definitive version is available at http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-923X.2007.00872.x Always use the definitive version when citing. Use Policy: The full-text may be used and/or reproduced and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not for profit purposes provided that: A full bibliographic reference is made to the original source A link is made to the metadata record in Newcastle E-prints The full text is not changed in any way. The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Robinson Library, University of Newcastle upon Tyne, Newcastle upon Tyne. NE1 7RU. Tel. 0191 222 6000 ‘About turn’: an analysis of the causes of the New Zealand Labour Party’s adoption of neo- liberal economic policies 1984-1990 John Reardon and Tim Gray School of Geography, Politics and Sociology Newcastle University Abstract This is the inside story of one of the most extraordinary about-turns in policy-making undertaken by a democratically elected political party. -

NEW ZEALAND GAZR'l*IE

No. 108 2483 THE NEW ZEALAND GAZR'l*IE Published by Authority WELLINGTON: THURSDAY, 31 OCTOBER 1974 Land Taken for the Auckland-Hamilton Motorway in the SCHEDULE City of Auckland NORTH AUCKlAND LAND DISTRICT ALL that piece of land containing 1 acre 3 roods 18.7 DENIS BLUNDELL, Governor-General perches situated in Block XIII, Whakarara Survey District, A PROCLAMATION and being part Matauri lHlB Block; as shown on plan PURSUANT to the Public Works Act 1928, I, Sir Edward M.O.W. 28101 (S.O. 47404) deposited in the office of the Denis Blundell, the Governor-General of New Zealand, hereby Minister of Works and Development at Wellington and proclaim and declare that the land first described in the thereon coloured blue. Schedule hereto and the undivided half share in the land Given under the hand of His Excellency the Governor secondly therein described, held by Melvis Avery, of Auck General and issued under the Seal of New Zealand, land, machinery inspector, are hereby taken for the Auckland this 23rd day of October 1974. Hamilton Motorway. [Ls.] HUGH WATT, Minister of Works and Development. SCHEDULE Goo SAVE THE QUEEN! NORTH AUCKLAND LAND DISTRICT (P.W. 33/831; Ak. D.O. 50/15/14/0/47404) ALL those pieces of land situated in the City of Auckland described as follows: A. R. P. Being Land Taken for Road and for the Use, Convenience, or 0 0 11.48 Lot 1, D.P. 12014. Enjoyment of a Road in Blocks Ill and VII, Te Mata 0 0 0.66 Lot 2, D.P. -

“The Next Generation in Iron Ore”

“The Next Generation in Iron Ore” Amex Resources Ltd (ASX(ASX::AXZ)AXZ) Amex Resources Ltd (‘Amex’) is an iron ore focused, mineral resources development company listed on the Australian Securities Exchange (ASX). The Company is currently concentrating on Feasibility Studies and Development of its Mba Delta Ironsand Project, in the Fiji Islands. Philosophy The Company’s philosophy is to: “To acquire, explore and develop mineral properties that show real potential for production of economic iron ore mineralisation, in order to increase shareholder wealth” Projects The Company’s focus is the Mba Delta Ironsand Project in Fiji. Amex also maintains an aggressive program of exploration and project generation. The Company’s project portfolio includes: • Mba Delta Ironsand Project, Viti Levu, Fiji – Development, • Mt Maguire Iron Ore Project, Ashburton, WA – Exploration, • Paraburdoo South Iron Ore Project, Pilbara, WA – Exploration, • Channar West Iron Ore Project, Pilbara, WA – Application. The Company continues to evaluate iron ore properties in the Asia-Pacific region for addition to its project portfolio. Recent Highlights Amex is currently completing Feasibility Studies over its Mba Delta Ironsand Project. Highlights from the Company’s exploration and development program include: • Increased JORC Resource and status upgraded to ‘Indicated’: 220 Million Tonnes @ 10.9% Fe (Iron) • Pilot plant commissioned and producing samples of concentrate for export from Fiji for evaluation by potential end users and strategic partners in China. • Concentrates high quality, grading >58% Fe through simple magnetic separation, with low impurities: 58.5% Fe & 0.65% V2O5 with 5.2% Al 2O3 0.37% CaO 0.05% K 20 3.4% MgO 0.04% Na 2O 0.03% P <0.01% S, 1.5% SiO 2 & 6.5% TiO 2. -

Archdes 701 | Advanced Design 2 | Topic Outline | Sem 2 2019

ARCHDES 701 | ADVANCED DESIGN 2 | TOPIC OUTLINE | SEM 2 2019 The Advanced Design 2 topics are structured around the theme of ‘urban patterns’. At their broadest, the topics foreground large-scale urban investigations concerning infrastructure, context, landscape, architecture, relationships between these factors and patterns of inhabitation thus supported. Crafted propositions are to be developed that demonstrate an exploration of the urban patterns theme across a range of scales. Andrew Douglas & Stacy Vallis Andrew has recently joined the School of Architecture & Planning. He has practiced architecture in Auckland & London, has a masters’ degree in Women’s Studies & a PhD in urBan theory from Goldsmiths, University of London. Stacy is a heritage specialist completing her PhD on the conservation and seismic upgrade of New Zealand’s unreinforced masonry Building precincts, at the School of Architecture & Planning. She has recently contributed to the international report “Future of our Pasts; Engaging Cultural Heritage in Climate Action” to address the implications of natural hazard and climate change for historic and cultural Building traditions. Tiny/Huge: City Adornment & Haptic Continuums A Douglas (2019). Upper Queen Street turns into Karangahape Road [photograph] GENERAL COURSE INFORMATION Course : Advanced Design 2 ARCHDES701 Points Value: 30 points Course Director: Andrew Douglas [email protected] Course Co-ordinator: Uwe Rieger [email protected] Studio Teachers: Andrew Douglas Stacy Vallis Contact: [email protected]/021 866 247 [email protected] Location: Level 3 Hours: Tuesday and Friday 1:00-5:00pm For all further general course information see the ARCHDES701 COURSE OUTLINE in the FILES folder on CANVAS. -

Public Safety and Nuisance Bylaw 2013

Te Ture ā-Rohe Marutau ā-Iwi me te Whakapōrearea 2013 Public Safety and Nuisance Bylaw 2013 (as at 11 January 2021) made by the Governing Body of Auckland Council in resolution GB/2013/84 on 22 August 2013 Bylaw made under sections 145, 146 and 149 of the Local Government Act 2002 and section 64 of the Health Act 1956. Summary This summary is not part of the Bylaw but explains the general effects. The purpose of this Bylaw is to help people to enjoy Auckland’s public places by – • identifying bad behaviours that must be avoided in public places in clause 6, for example disturbing other people or using an object in a way that is dangerous or causes a nuisance • identifying restricted activities in Schedule 1, for example, fireworks, drones, fences, fires, weapons, storing objects, camping or set netting • enabling the restriction of certain activities and access to public places in clauses 7, 8 and 10. Other parts of this Bylaw assist with its administration by – • stating the name of this Bylaw and when it comes into force in clauses 1 and 2 • stating where and when this Bylaw applies in clause 3, in particular that it does not apply to issues covered in other Auckland Council, Auckland Transport or Maunga Authority bylaws • stating the purpose of this Bylaw and defining terms used in clauses 4 and 5 • providing transparency about how decisions are made under this Bylaw in clauses 9 and 11 • referencing Council’s powers to enforce this Bylaw, including powers to take property and penalties up to $20,000 in clauses 12, 13 and 14 • ensuring decisions made prior to amendments coming into force on 01 October 2019 continue to apply in Clause 15 • providing time for bylaw provisions about vehicles to be addressed under the Auckland Council Traffic Bylaw 2015 in clause 16. -

IN the MATTER of the Resource Management Act 1991 and in THE

IN THE MATTER of the Resource Management Act 1991 AND IN THE MATTER of a Board of Inquiry appointed under s149J of the Resource Management Act 1991 to consider Notice of Requirements and applications for Resource Consent made by the New Zealand Transport Agency in relation to the East West Link roading proposal in Auckland. STATEMENT OF EVIDENCE LEMAUNGA LYDIA SOSENE ON BEHALF OF THE MANGERE-OTAHUHU LOCAL BOARD CONTENTS CLAUSE PAGE 1. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................. 1 2. MOLB'S VIEWS ON THE PROPOSAL ............................................................................ 1 3. GENERAL ....................................................................................................................... 3 Lemaunga Sosene_ Board Member _ FINAL need signature - 29238877 v 1.DOC 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1 My name is Lemauga Lydia Sosene. I am the Local board chairperson of the Mangere-Otahuhu Local Board (MOLB or board). 1.2 The Mangere-Otahuhu Local Board (the Board) supports the proposed East- West Link development in principle, subject to some comments on specific matters set out below. 1.3 The Board also supports the general objective of this development, such as, improved access ways and facilities between SH20 and SH1 along the northern edge of the Mangere inlet and surrounding areas, including the Princes Street junction for vehicles, cyclists and pedestrian safety. 1.4 The East-West Link Connection development aligns with key transport priorities set in the Mangere-Otahuhu Board Plan’s outcome “A well- connected area”: Improving connections in our area through safer streets, quality public transport, cycle ways and greenways. to live in a place that is easy to travel around. This is important to the well- being of our community... crucial to delivering our economic aims of developing tourism and growing businesses in our area. -

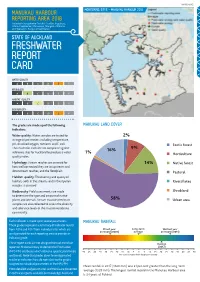

Freshwater Report Card

19-PRO-0142 MANUKAU HARBOUR MONITORING SITES – MANUKAU HARBOUR 2018 REPORTING AREA 2018 Includes Maungakiekie-Tamaki, Franklin, Papakura, Ōtara-Papatoetoe, Manurewa, Mangere-Otahuhu and Waitakere Ranges Local Boards STATE OF AUCKLAND FRESHWATER REPORT CARD WATER QUALITY A B C D E F HYDROLOGY A B C D E F HABITAT QUALITY A B C D E F BIODIVERSITY A B C D E F The grades are made up of the following MANUKAU LAND COVER indicators: Water quality: Water samples are tested for 2% a range of parameters including temperature, pH, dissolved oxygen, nutrients and E. coli. Exotic forest The results for each site are compared against 16% 9% reference sites for Auckland to produce a water 1% Horticulture quality index. Hydrology: Stream reaches are assessed for 14% Native forest how well connected they are to upstream and downstream reaches, and the floodplain. Pastoral Habitat quality: The diversity and quality of habitats both in the streams and in the riparian Rivers/lakes margins is assessed. Biodiversity: Field assessments are made Shrubland to determine the type and amount of native plants and animals. Stream macroinvertebrate 58% Urban area samples are also collected to assess the diversity and tolerance levels of the macroinvertebrate community. Each indicator is made up of several parameters. MANUKAU RAINFALL These grades represent a summary of indicator results from 2016 and 2017 from individual sites which are Driest year Wettest year on record (2002) on record (2011) amalgamated for each reporting area to provide an indicator grade. These report cards are not designed to track trends or Rainfall report on National Policy Statement for Freshwater (2017) (NPS-FM) attributes which relate to specific parameters and bands. -

Board of Airline Representatives New

BOARD OF AIRLINE REPRESENTATIVES OF NEW ZEALAND LAND VALUATION AUCKLAND AIRPORT - MARKET VALUE ALTERNATIVE USE MARCH 2013 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 INSTRUCTIONS .................................................................................................................... 1 2.0 PROPERTY REPORT ............................................................................................................. 2 2.1 GENERAL PROPERTY DESCRIPTION ..................................................................................... 2 2.2 LEGAL DESCRIPTION & TENURE ............................................................................................. 4 2.3 RESOURCE MANAGEMENT & ZONING .................................................................................. 7 3.0 VALUATION OF MVAU LAND ............................................................................................... 8 3.1 METHODOLOGY .................................................................................................................. 8 3.2 VALUATION CONSIDERATIONS ............................................................................................. 9 4.0 DETAILED MVAU VALUATION ........................................................................................... 10 4.1 (A) & (B) AIAL LAND HOLDINGS ........................................................................................ 10 4.2 (C) & (D) HIGHEST & BEST ALTERNATIVE USE ASSESSMENT ............................................... 10 4.3 (E) RESOURCE MANAGEMENT / AMENITIES / DEVELOPMENT -

Writings Ignited a Powder Keg Key Events Alumni Speakers Staff, Students and the Public Can Hear the Distinguished Alumni Awardees Discussing Their Life and Work

Fortnightly newsletter for University staff | Volume 39 | Issue 3 | 27 February 2009 Writings ignited a powder keg Key events Alumni speakers Staff, students and the public can hear the Distinguished Alumni Awardees discussing their life and work. A Distinguished Alumni Speaker Day is being held on Saturday 14 March, the day after the gala dinner to honour them.There are five concurrent talks between mid-morning and early afternoon in the Owen G Glenn Building and the Fale Pasifika: Children’s author Lynley Dodd: “Going to the dogs” (10.30-11.30am); the Samoan Prime Minister, the Rt Hon Tuilaepa Malielegaoi: “Survival in the turbulent sea of change of island politics in the calm and peace of the Pacific Ocean” (10.30-11.30am); businessman Richard Chandler (in conversation with the Rt Hon Mike Moore): “Building prosperity for tomorrow’s world” (12noon- 1.15pm); playwright and film-maker Toa Fraser: “Animal tangles: That’s the carnal and the Allen Rodrigo and Brian Boyd at the Fale Pasifika during the symposium. heavenly right there” (12noon-1pm); the Rt Hon A free public all-day symposium on the lasting reverberations can still be felt today. His legacy has Sir Douglas Graham: “Maori representation in legacy of Charles Darwin attracted a crowd that extended beyond biology, beyond natural science Parliament” (12noon-1pm). filled the large Fisher and Paykel Auditorium in and into the humanities and social sciences.” RSVP at www.auckland.ac.nz/speaker-day or the Owen G Glenn Building, and at times This breadth of Darwin’s influence was borne email [email protected] overflowed into a second venue.