The Development of Southern Min Demonstratives + Type Classifier

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

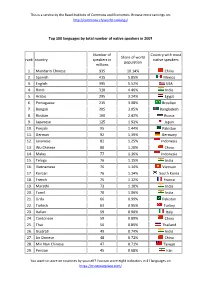

Top 100 Languages by Total Number of Native Speakers in 2007 Rank

This is a service by the Basel Institute of Commons and Economics. Browse more rankings on: http://commons.ch/world-rankings/ Top 100 languages by total number of native speakers in 2007 Number of Country with most Share of world rank country speakers in native speakers population millions 1. Mandarin Chinese 935 10.14% China 2. Spanish 415 5.85% Mexico 3. English 395 5.52% USA 4. Hindi 310 4.46% India 5. Arabic 295 3.24% Egypt 6. Portuguese 215 3.08% Brasilien 7. Bengali 205 3.05% Bangladesh 8. Russian 160 2.42% Russia 9. Japanese 125 1.92% Japan 10. Punjabi 95 1.44% Pakistan 11. German 92 1.39% Germany 12. Javanese 82 1.25% Indonesia 13. Wu Chinese 80 1.20% China 14. Malay 77 1.16% Indonesia 15. Telugu 76 1.15% India 16. Vietnamese 76 1.14% Vietnam 17. Korean 76 1.14% South Korea 18. French 75 1.12% France 19. Marathi 73 1.10% India 20. Tamil 70 1.06% India 21. Urdu 66 0.99% Pakistan 22. Turkish 63 0.95% Turkey 23. Italian 59 0.90% Italy 24. Cantonese 59 0.89% China 25. Thai 56 0.85% Thailand 26. Gujarati 49 0.74% India 27. Jin Chinese 48 0.72% China 28. Min Nan Chinese 47 0.71% Taiwan 29. Persian 45 0.68% Iran You want to score on countries by yourself? You can score eight indicators in 41 languages on https://trustyourplace.com/ This is a service by the Basel Institute of Commons and Economics. -

Congressional-Executive Commission on China

CONGRESSIONAL-EXECUTIVE COMMISSION ON CHINA ANNUAL REPORT 2008 ONE HUNDRED TENTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION OCTOBER 31, 2008 Printed for the use of the Congressional-Executive Commission on China ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.cecc.gov VerDate Aug 31 2005 23:54 Nov 06, 2008 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 6011 Sfmt 5011 U:\DOCS\45233.TXT DEIDRE 2008 ANNUAL REPORT VerDate Aug 31 2005 23:54 Nov 06, 2008 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00002 Fmt 6019 Sfmt 6019 U:\DOCS\45233.TXT DEIDRE CONGRESSIONAL-EXECUTIVE COMMISSION ON CHINA ANNUAL REPORT 2008 ONE HUNDRED TENTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION OCTOBER 31, 2008 Printed for the use of the Congressional-Executive Commission on China ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.cecc.gov U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE ★ 44–748 PDF WASHINGTON : 2008 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate Aug 31 2005 23:54 Nov 06, 2008 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00003 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 U:\DOCS\45233.TXT DEIDRE CONGRESSIONAL-EXECUTIVE COMMISSION ON CHINA LEGISLATIVE BRANCH COMMISSIONERS House Senate SANDER LEVIN, Michigan, Chairman BYRON DORGAN, North Dakota, Co-Chairman MARCY KAPTUR, Ohio MAX BAUCUS, Montana TOM UDALL, New Mexico CARL LEVIN, Michigan MICHAEL M. HONDA, California DIANNE FEINSTEIN, California TIMOTHY J. WALZ, Minnesota SHERROD BROWN, Ohio CHRISTOPHER H. SMITH, New Jersey CHUCK HAGEL, Nebraska EDWARD R. ROYCE, California SAM BROWNBACK, Kansas DONALD A. -

Construction and Automatization of a Minnan Child Speech Corpus with Some Research Findings

Computational Linguistics and Chinese Language Processing Vol. 12, No. 4, December 2007, pp. 411-442 411 © The Association for Computational Linguistics and Chinese Language Processing Construction and Automatization of a Minnan Child Speech Corpus with some Research Findings Jane S. Tsay∗ Abstract Taiwanese Child Language Corpus (TAICORP) is a corpus based on spontaneous conversations between young children and their adult caretakers in Minnan (Taiwan Southern Min) speaking families in Chiayi County, Taiwan. This corpus is special in several ways: (1) It is a Minnan corpus; (2) It is a speech-based corpus; (3) It is a corpus of a language that does not yet have a conventionalized orthography; (4) It is a collection of longitudinal child language data; (5) It is one of the largest child corpora in the world with about two million syllables in 497,426 lines (utterances) based on about 330 hours of recordings. Regarding the format, TAICORP adopted the Child Language Data Exchange System (CHILDES) [MacWhinney and Snow 1985; MacWhinney 1995] for transcribing and coding the recordings into machine-readable text. The goals of this paper are to introduce the construction of this speech-based corpus and at the same time to discuss some problems and challenges encountered. The development of an automatic word segmentation program with a spell-checker is also discussed. Finally, some findings in syllable distribution are reported. Keywords: Minnan, Taiwan Southern Min, Taiwanese, Speech Corpus, Child Language, CHILDES, Automatic Word Segmentation 1. Introduction Taiwanese Child Language Corpus is a corpus based on spontaneous conversations between young children and their adult caretakers in Minnan speaking families in Chiayi County, Taiwan. -

Post-Cold War Experimental Theatre of China: Staging Globalisation and Its Resistance

Post-Cold War Experimental Theatre of China: Staging Globalisation and Its Resistance Zheyu Wei A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The School of Creative Arts The University of Dublin, Trinity College 2017 Declaration I declare that this thesis has not been submitted as an exercise for a degree at this or any other university and it is my own work. I agree to deposit this thesis in the University’s open access institutional repository or allow the library to do so on my behalf, subject to Irish Copyright Legislation and Trinity College Library Conditions of use and acknowledgement. ___________________ Zheyu Wei ii Summary This thesis is a study of Chinese experimental theatre from the year 1990 to the year 2014, to examine the involvement of Chinese theatre in the process of globalisation – the increasingly intensified relationship between places that are far away from one another but that are connected by the movement of flows on a global scale and the consciousness of the world as a whole. The central argument of this thesis is that Chinese post-Cold War experimental theatre has been greatly influenced by the trend of globalisation. This dissertation discusses the work of a number of representative figures in the “Little Theatre Movement” in mainland China since the 1980s, e.g. Lin Zhaohua, Meng Jinghui, Zhang Xian, etc., whose theatrical experiments have had a strong impact on the development of contemporary Chinese theatre, and inspired a younger generation of theatre practitioners. Through both close reading of literary and visual texts, and the inspection of secondary texts such as interviews and commentaries, an overview of performances mirroring the age-old Chinese culture’s struggle under the unprecedented modernising and globalising pressure in the post-Cold War period will be provided. -

THE MEDIA's INFLUENCE on SUCCESS and FAILURE of DIALECTS: the CASE of CANTONESE and SHAAN'xi DIALECTS Yuhan Mao a Thesis Su

THE MEDIA’S INFLUENCE ON SUCCESS AND FAILURE OF DIALECTS: THE CASE OF CANTONESE AND SHAAN’XI DIALECTS Yuhan Mao A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts (Language and Communication) School of Language and Communication National Institute of Development Administration 2013 ABSTRACT Title of Thesis The Media’s Influence on Success and Failure of Dialects: The Case of Cantonese and Shaan’xi Dialects Author Miss Yuhan Mao Degree Master of Arts in Language and Communication Year 2013 In this thesis the researcher addresses an important set of issues - how language maintenance (LM) between dominant and vernacular varieties of speech (also known as dialects) - are conditioned by increasingly globalized mass media industries. In particular, how the television and film industries (as an outgrowth of the mass media) related to social dialectology help maintain and promote one regional variety of speech over others is examined. These issues and data addressed in the current study have the potential to make a contribution to the current understanding of social dialectology literature - a sub-branch of sociolinguistics - particularly with respect to LM literature. The researcher adopts a multi-method approach (literature review, interviews and observations) to collect and analyze data. The researcher found support to confirm two positive correlations: the correlative relationship between the number of productions of dialectal television series (and films) and the distribution of the dialect in question, as well as the number of dialectal speakers and the maintenance of the dialect under investigation. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The author would like to express sincere thanks to my advisors and all the people who gave me invaluable suggestions and help. -

Ethnic Nationalist Challenge to Multi-Ethnic State: Inner Mongolia and China

ETHNIC NATIONALIST CHALLENGE TO MULTI-ETHNIC STATE: INNER MONGOLIA AND CHINA Temtsel Hao 12.2000 Thesis submitted to the University of London in partial fulfilment of the requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in International Relations, London School of Economics and Political Science, University of London. UMI Number: U159292 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U159292 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 T h c~5 F . 7^37 ( Potmc^ ^ Lo « D ^(c st' ’’Tnrtrr*' ABSTRACT This thesis examines the resurgence of Mongolian nationalism since the onset of the reforms in China in 1979 and the impact of this resurgence on the legitimacy of the Chinese state. The period of reform has witnessed the revival of nationalist sentiments not only of the Mongols, but also of the Han Chinese (and other national minorities). This development has given rise to two related issues: first, what accounts for the resurgence itself; and second, does it challenge the basis of China’s national identity and of the legitimacy of the state as these concepts have previously been understood. -

ISO 639-3 Code Split Request Template

ISO 639-3 Registration Authority Request for Change to ISO 639-3 Language Code Change Request Number: 2019-062 (completed by Registration authority) Date: 2019 Aug 31 Primary Person submitting request: Kirk Miller E-mail address: kirkmiller at gmail dot com Names, affiliations and email addresses of additional supporters of this request: PLEASE NOTE: This completed form will become part of the public record of this change request and the history of the ISO 639-3 code set and will be posted on the ISO 639-3 website. Types of change requests Type of change proposed (check one): 1. Modify reference information for an existing language code element 2. Propose a new macrolanguage or modify a macrolanguage group 3. Retire a language code element from use (duplicate or non-existent) 4. Expand the denotation of a code element through the merging one or more language code elements into it (retiring the latter group of code elements) 5. Split a language code element into two or more new code elements 6. Create a code element for a previously unidentified language For proposing a change to an existing code element, please identify: Affected ISO 639-3 identifier: nan Associated reference name: Min Nan Chinese 5. Split a language code element into two or more code elements (a) List the languages into which this code element should be split: Hokkien / Hoklo / Quanzhang Chinese Chaoshan Min / Teo-Swa Chinese Datian Min Chinese Leizhou Min Chinese Hainanese Min / Qiong Wen Chinese (b) Referring to the criteria given above, give the rationale for splitting the existing code element into two or more languages: The varieties of Min Nan are not mutually intelligible. -

Kim Jung Min Chinese Stealth Foreign Policy: Immigration

Kim Jung Min 37 UDC 314.17 Kim Jung Min National University of Mongolia, Mongolia, Ulan Bator E-mail: [email protected] Chinese Stealth Foreign Policy: Immigration Kazakhstan has been focusing on the energy diplomacy with China more than Russia or the Western nations. China has been successful in terms of their access to secure the energy security through economic relations without stimulating the U.S. or Russia for advancing to the Central Asian region. But traditionally as for the region that Chinese began to influence economically, there were cases in which commercial supremacy were frequently gained by the overseas Chinese. The regions where the current overseas Chinese cannot economically influence are such developed nations as the Europe, the U.S., and Japan and as for the cases of such developing nations as the EastAsia, the overseas Chinese who cover about 10% of the entire population dominate more than 50% of local economy for the most part. Accordingly, if the expansion of the economical relations between Kazakhstan and China causes the immigration of the overseas Chinese in the future, it is presumed that similar situations will also occur in Kazakhstan like South East Asia, because Chinese immigration is a part of Chinese foreign policy to get energy security. Key words: Immigration, Chinese, Southeast Asia, Chinese foreign investment, Jeju island Ким Джонг Мин Қы тай дың сыртқы саяса ты ның бүр ке ме лі ерек ше лік те рі: им миг ра ция Соң ғы кез де, Қа зақстан энер ге ти ка лық дип ло ма тияда Ре сей не ме се Ба тыс ел де рі не қа ра ған да, Қы тай ға кө бі рек кө ңіл бө лу де. -

Modeling Taiwanese Southern-Min Tone Sandhi Using Rule-Based Methods

Computational Linguistics and Chinese Language Processing Vol. 12, No. 4, December 2007, pp. 349-370 The Association for Computational Linguistics and Chinese Language Processing Modeling Taiwanese Southern-Min Tone Sandhi Using Rule-Based Methods Un-Gian Iunn*, Kiat-Gak Lau+, Hong-Giau Tan-Tenn, Sheng-An Lee*, and Cheng-Yan Kao* Abstract A sizable corpus of Taiwanese text in Latin script has been accumulated over the past two hundred or so years. However, due to the special status of Taiwan, few people can read these materials at present. It is regrettable that the utilization of these plentiful materials is very low. This paper addresses problems raised in the Taiwanese Southern-Min tone sandhi system by describing a set of computational rules to approximate this system, as well as the results obtained from its implementation. Using the romanized Taiwanese Southern-Min text as source, we take the sentence as the unit, translate every word into Chinese via an online Taiwanese-Chinese dictionary (OTCD), and obtain the part-of-speech (POS) information from the Chinese Electronic Dictionary (CED) made by the Chinese Knowledge and Information Processing (CKIP) group of Academia Sinica. By using the POS data and tone sandhi rules based on linguistics, we then tag each syllable with its post-sandhi tone marker. Finally, we implement a Taiwanese Southern-Min tone sandhi processing system which takes a romanized sentence as an input and then outputs the tone markers. Our system achieves 97.39% and 88.98% accuracy rates with training and test data, respectively. Finally, we analyze the factors influencing error for the purpose of future improvement. -

ISO 639-3 Code Split Request Template

ISO 639-3 Registration Authority Request for Change to ISO 639-3 Language Code Change Request Number: 2019-065 (completed by Registration authority) Date: August 31, 2019 Primary Person submitting request: Kirk Miller Affiliation: E-mail address: kirkmiller at gmail dot com Names, affiliations and email addresses of additional supporters of this request: Postal address for primary contact person for this request (in general, email correspondence will be used): PLEASE NOTE: This completed form will become part of the public record of this change request and the history of the ISO 639-3 code set and will be posted on the ISO 639-3 website. Types of change requests This form is to be used in requesting changes (whether creation, modification, or deletion) to elements of the ISO 639 Codes for the representation of names of languages — Part 3: Alpha-3 code for comprehensive coverage of languages. The types of changes that are possible are to 1) modify the reference information for an existing code element, 2) propose a new macrolanguage or modify a macrolanguage group; 3) retire a code element from use, including merging its scope of denotation into that of another code element, 4) split an existing code element into two or more new language code elements, or 5) create a new code element for a previously unidentified language variety. Fill out section 1, 2, 3, 4, or 5 below as appropriate, and the final section documenting the sources of your information. The process by which a change is received, reviewed and adopted is summarized on the final page of this form. -

Summary of Requested Changes Altogether 66 Requests Were Considered, Recommending 116 Explicit Changes in the Code Set

ISO 639-3 Change Requests Series 2019 Summary of Outcomes Melinda Lyons (SIL International), ISO 639-3 Registrar, 23 January 2020 Summary of requested changes Altogether 66 requests were considered, recommending 116 explicit changes in the code set. Of the 66 change requests, 16 have been rejected, 44 have been fully approved, 2 were partially approved, and two were withdrawn. Four requests are awaiting additional information for final consideration. Of the 106 explicit changes to individual codes which were decided, 45 were rejected and 61 accepted. The latter can be analyzed as follows: Deprecations (Retirements): o 12 deprecated as non-existent; o 1 deprecated as duplicate of another code; o 4 deprecated and merged into another language; o 3 split languages. New languages: o 11 newly created languages not previously associated with another language in the code set; o 14 languages created as a result of splits. Updates: o 11 name updates, either change to a name form or addition of a name form o 4 updates to denotation of a language code as a result of mergers o 1 update to membership of a macrolanguage. In addition to the numbered and posted change requests for 2019, there were a number of routine maintenance updates. 11 language types were changed from extinct to ancient and 15 were changed from extinct to historic. The history of any change request may be viewed on its documentation page which uses the pattern: https://iso639-3.sil.org/request/2019-004 Likewise, the history of any code element may be viewed on its documentation -

Variegated VC Rime Restrictions in Sinitic Languages*

Variegated VC Rime Restrictions in Sinitic Languages * Chiachih Lo, Feng-fan Hsieh, and Yueh-chin Chang National Tsing Hua University 1 Introduction Restrictions on the nucleus+coda combinations in Sinitic languages have been conventionally analyzed as co-occurrence markedness constraints, e.g., RIME HARMONY (Duanmu 2000, 2003, Lin 1989, among others) for Standard Chinese, or, *IK (*[-cons, +hi][+cons, +hi]) for Cantonese (Kenstowicz 2012, see also, e.g., Cheng 1991). However, these monolithic markedness constraints not only fail to provide a motive force behind these restrictions, but also overgenerate by predicting unattested gaps. 1 To name a few, RIME HARMONY disallows the nucleus and post-nuclear elements to differ in [round] and [back] values. But violations of this (configurational) constraint are not uncommon in Sinitic languages. For example, we see in Table 1 that -ot is legitimate in Hakka and Cantonese, and -ut is attested in Taiwanese Southern Min (henceforth Taiwanese). Second, no restrictions are found when the nucleus vowel is /a/ and when the coda is “placeless” (i.e., -ʔ). Third, no account is provided for why /e/ is more restricted than /i/ in VC rimes, given that they are both front vowels. Finally, and more importantly, we can see in Table 1 that the back vowels {u, o/ɔ} are in complementary distribution in Taiwanese VC rimes but that is not the case for the comparable VC combinations in Hakka and Cantonese. The above observations raise the question whether non-existing, impermissible VC rimes can merely be explained away by re-ranking markedness and faithfulness constraints for the rime gaps in different Sinitic languages.